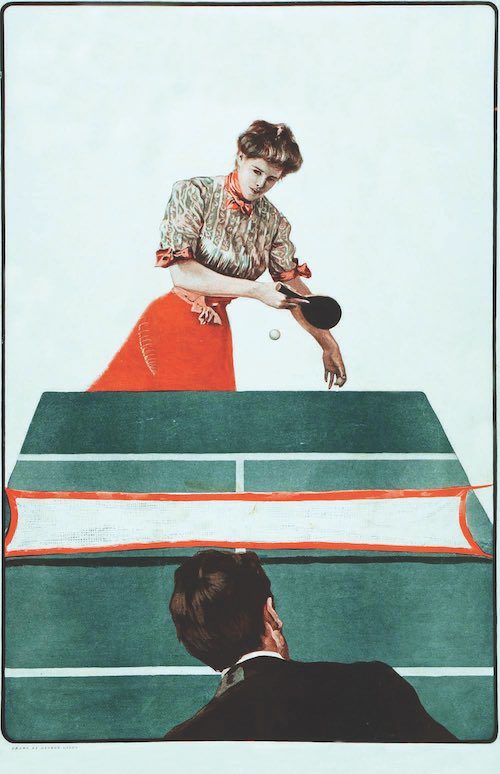

The 20th Century’s First Big Craze: Ping-Pong

Séances, bicycles, automobiles — they’d all been fads. But at the turn of the century, America had lost its mind over Ping-Pong, a game Post editors called “cheap, safe, easily learned, gently invigorating, and fascinating.” The following editorial appear in the Post on April 5, 1902.

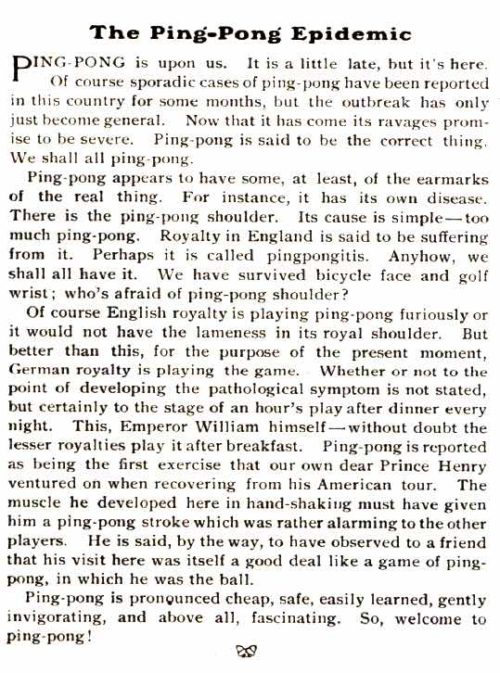

Can You Identify the 31 Jobs in Rockwell’s “Rosie to the Rescue”?

Norman Rockwell

September 4, 1943

In 1943, several major magazines agreed to salute the women war workers of America on their September covers. The Post gave the assignment to Rockwell, who’d already created an iconic tribute to women defense workers with Rosie the Riveter.

For this new cover, he wanted to acknowledge the wide range of jobs that 15 million women had taken up as men went off to war. The result was Rosie to the Rescue, which showed a woman bearing the symbols and tools of several trades hurrying off to her next job. The Post editors claimed 31 different occupations were represented on this cover. Some were jobs traditionally associated with women: cleaning, farming, nursing, and clerical work. Others, indicated by tools such as an electric cable and a monkey wrench, referred to industrial occupations that women were starting to enter in great number.

The cover not only acknowledges women war workers, it also recalls occupations of the 1940s that once employed thousands. Post readers of the day would have instantly recognized the bus-driver’s ticket punch, a taxi-driver’s change dispenser, a milkman’s bottle rack, a switchboard operator’s headset, and the blue cap of a train conductor. The railroad industry was also represented by the railroad section hand’s lantern, the locomotive engineer’s oil can, and that round object swinging on a shoulder strap — a clock used by night watchwomen in railway yards.

Here is what the Post editors had to say about this image in the “Keeping Posted” section of our September 4, 1943 issue:

At least thirty-one wartime occupations for women are suggested by Norman Rockwell’s remarkable Labor Day Post cover. Perhaps you can think of more. The thirty-one we counted, suggested by articles the young lady is carrying or wearing, are: boardinghouse manager and housekeeper (keys on ring); chambermaid, cleaner and household worker (dust pan and brush, mop); service superintendent (time clock); switchboard operator and telephone operator (earphone and mouthpiece); grocery-store woman and milk-truck driver (milk bottles); electrician for repair and maintenance of household appliances and furnishings (electric wire); plumber and garage mechanic (monkey wrench, small wrenches); seamstress (big scissors); typewriter-repair woman, stenographer, typist, editor and reporter (typewriter); baggage clerk (baggage checks); bus driver (puncher); conductor on railroad, trolley, bus (conductor’s cap); filling-station attendant and taxi driver (change holder); oiler on railroad (oil can); section hand (red lantern); bookkeeper (pencil over ear); farm worker (hoe and potato fork); truck farmer (watering can); teacher (schoolbooks and ruler); public health, hospital or industrial nurse (Nurses’ Aide cap). —“Keeping Posted: The Rockwell Cover,” September 4, 1943.

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Technology Was Killing Attention Spans 115 Years Ago

People are too easily distracted. News of a major tragedy will hold their interest for a few days, but boredom quickly sets in and attention drifts away.

That’s what the Post editors concluded after people learned a hurricane had destroyed a major American city on the Gulf Coast. “Money and food were sent,” they wrote. “The heart of the country went out in sympathy. The awful story was eagerly read. But by the third day there was a distinct falling off in interest. … By the [fifth day] even the headlines were not looked at.”

They weren’t describing New Orleans in 2005, but Galveston in 1900.

In September of that year, a hurricane swept inland to destroy a city and kill some 10,000 people, making it still the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. It was, of course, a major news story. Yet two months later, Post editors observed that people had quickly lost interest in the tragedy.

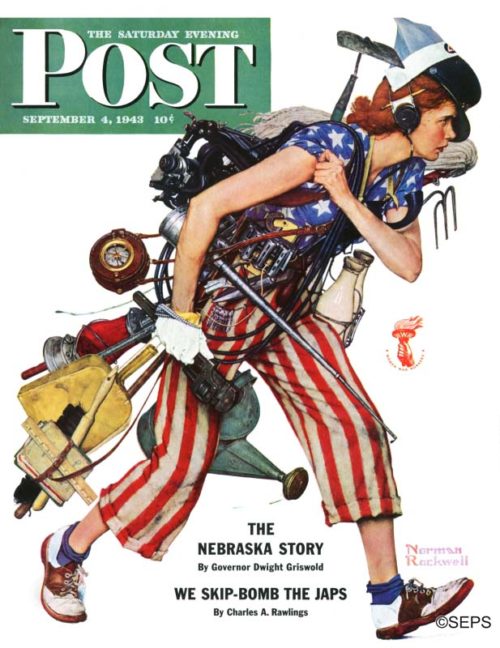

The editorial — published nearly a century before life became enmeshed with the Web and smartphones — blamed technology for the lack of focus. Life was becoming too fast-paced. Rapid communication, made possible by steamships, the telegraph, and the new telephone, was making people impatient with any delay. Even the kinetoscope, Edison’s patented personal hand-cranked movie viewer (pictured above), was contributing to America’s growing inability to stay focused.

We can smile at the thought that steamships were making people more distracted. But it appears that technology does indeed make it harder for us to concentrate. This year, the Microsoft Corporation published a study that showed between the year 2000 and 2013 the average attention span dropped from 12 to 8 seconds. That’s one second less than the attention span of a goldfish.

If true, this fact suggests that people will find it increasingly difficult to remember and learn from tragedy. And if that’s the case, maybe we should heed the editors’ advice from 115 years ago: “But it were well if, with all our increasing swiftness, we should stop and think a while now and then.”

Classic Covers: Father’s Day, 1950s Style

Enter the prosperous 1950s, when Dad was king of his suburban castle. The nuclear family had followed the new interstate system right out of the city and settled into small communities of manicured lawns, picture windows, and Sunday barbecues. And Dad outside the city limits proved to be a perfect character for the situational comedies portrayed on Post covers. Join us in a fun look at ’50s dads (or should we say daddy-os?). They just may remind you of someone you love.

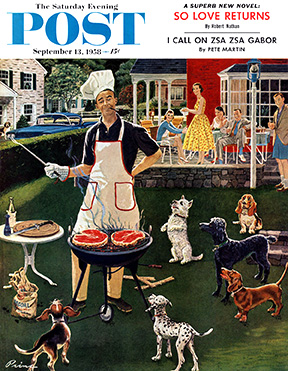

Pop vs. Pup

Ben Prins

September 13, 1958

© SEPS

Sending out smoke signals has made this dad popular with more than just his family. Artist Ben Prins got the idea for the cover while outside feeding his children’s three cats. Post editors wrote that dogs would “drop around to pass the time of day” during chow time at the Prins residence.

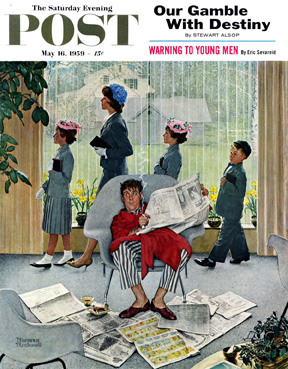

Bad Dad

Norman Rockwell

May 16, 1959

© SEPS

“This is my favorite Post cover for Father’s Day,” emailed reader Bob McGowan of California. “It’s best known as Sunday Morning, but I’ve nicknamed it ‘Bad Dad,’ as he knows he should be dressed in his Sunday best, also headed out the door to church with Mom and the youngsters.” [See how to get your favorite covers featured below.]

Rockwell’s obsession with detail shows in this 1959 cover. He went to several furniture stores until he found just the right chair for this “bad dad” to slink in. And, if you click on the image for a close-up view, you’ll see a more mischievous detail: The artist arranged “horns” into the sinner’s disheveled hair.

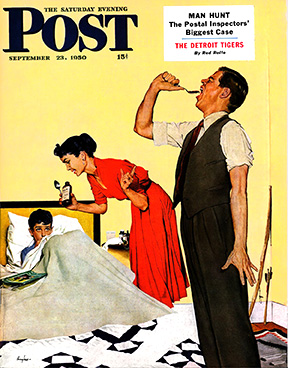

Father Figure

George Hughes

September 23, 1950

© SEPS

Is there no sacrifice too great for Dad? The problem with proving that the medicine is not so repulsive is that Pop is a lousy actor. Even without the giveaway expression, editors noted, “Junior wouldn’t have fallen for the treachery. Every youngster learns at the dinner table to mistrust what his parents say tastes fine until he finds out for himself.” Artist George Hughes, who did 115 Post covers, knew all about parental scams: He had five daughters.

Gone Daddy Gone

George Hughes

June 12, 1954

© SEPS

“It is heartwarming,” wrote Post editors of this Hughes cover, “to see how this boy trusts his father to halt that vehicle before both teacher and pupil land on their ears. It is heart-chilling to see how the father doesn’t.”

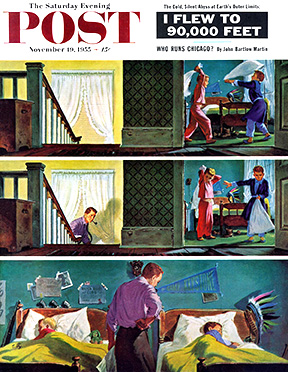

Father Knows Best?

Thornton Utz

November 19, 1955

© SEPS

“Old folks are so fussy about noises at night,” wrote Post editors of this 1955 cover. “They hear a burglar, and they grope downstairs, and there is none, or they hear a pillow fight, and grope upstairs, and there is none. If [artist] Thornton Utz’s father doesn’t stop fussing around, he’ll wake those boys up.” Right. This dad isn’t buying it; the readers aren’t buying it; and, admit it, neither did your dad.

Do you have a favorite Post cover? Tell us about it and we’ll feature it with your comments in an upcoming cover art piece! If you don’t know the date or artist, just give us a brief description. Send to [email protected].

See our collection of cover art here.

Art Licensing

For licensing information, please visit curtispublishing.com,

call 317-633-2070, or email [email protected].

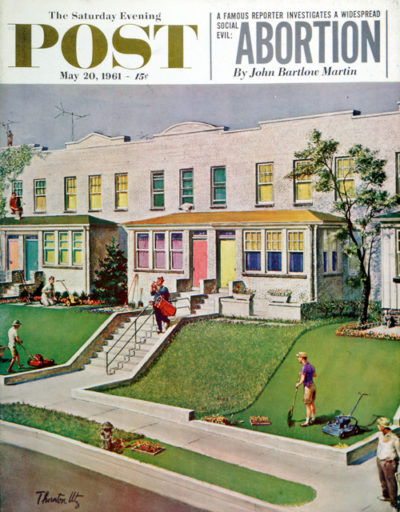

Classic Covers: Yard Work

From mowing and tree planting to a neighborhood nonconformist, 1950s-style, these timeless covers are just in time to inspire you to tackle that yard.

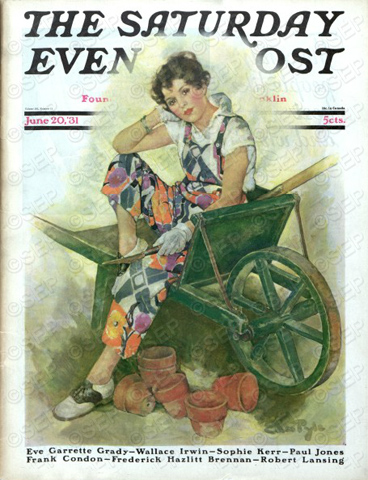

Woman in Wheelbarrow

Ellen Pyle

June 20, 1931

Ellen Pyle (1876-1936) was known for her beautiful use of color. In 1927, she received a note from fellow cover artist Norman Rockwell about how much he liked her Post covers. “They are dandy. So full of color and so broadly painted. Believe me I envy you the latter quality particularly,” he wrote, according to Delaware Art Museum’s Illustrating Her World: Ellen B. T. Pyle.

As in many of her 40 covers for the Post, the model is one of Pyle’s children. In this case, teenage daughter Caroline is taking a wheelbarrow break from gardening duties.

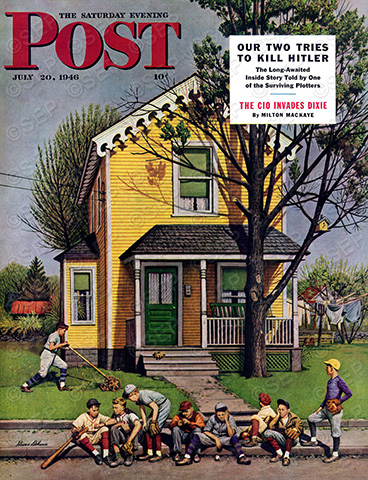

Baseball Player Mowing the Lawn

Stevan Dohanos

July 20, 1946

“When summer rolled around,” wrote Post editors of this 1946 cover, “and the grass in Westport, Connecticut, began to grow as fast as a small boy’s hair, Stevan Dohanos recalled one of the duties of his youth and how mowing the lawn can ball up a man’s more important engagements.”

The frame house, however, was not in Connecticut, but back in artist Dohanos’ (1907-1994) hometown of Lorain, Ohio. Editors noted that he sketched it a couple years before it appeared on the cover. “Obviously it was a good stage, a good setting, but he never had decided just what story to tell against this background. Now he uses it to tell of a common summertime crisis—when the star pitcher has to work,” Post editors wrote.

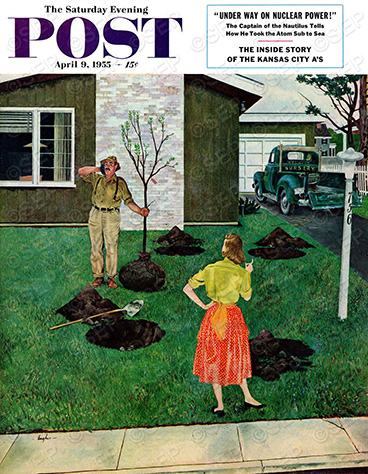

Put the Tree There?

George Hughes

April 9, 1955

Illustrator George Hughes (1907-1990) was an avid outdoorsman, but we’re not sure how he felt about planting trees. He would probably feel the same as the poor guy from the local nursery on this 1955 cover, if he had to deal with an indecisive homeowner.

Hughes painted 115 Post covers, and was especially productive in the 1950s. Typical output for the more popular illustrators was around 40 to 50 covers during a decade. Hughes’ friend Norman Rockwell, for example, did 44 during this period. Hughes did 80 in this timeframe; mostly fun, slice-of-life scenes from midcentury suburban life.

View more in the George Hughes gallery.

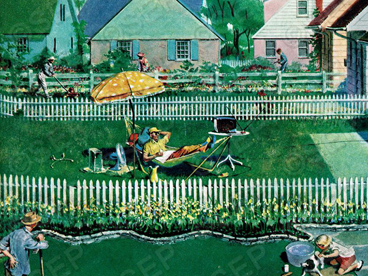

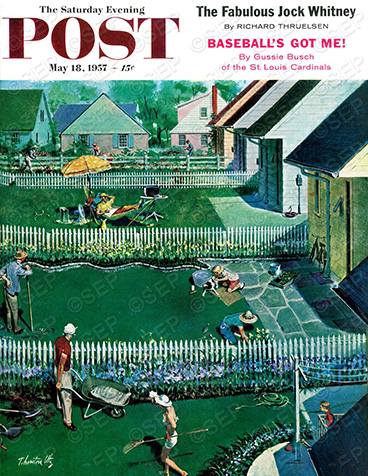

Artist Thornton Utz (1914-2000) enjoyed gently bucking the trend and depicting the neighborhood nonconformist. Mr. Leisure in this 1957 cover uses his backyard purely for relaxation, not caring how high the grass gets.

Meanwhile, in nearby yards, neighbors are flummoxed by Mr. Leisure’s indifference—at least those who can spare a second from their suburban chores.

Spring Yard Work

Thornton Utz

May 18, 1957

Even the little girl in the middle yard wastes no time as she tends to her dog’s bath. Post editors mused that the cover might start a debate “about whether people should nourish their backyards or let their backyards nourish them.” We’ll let the reader decide.

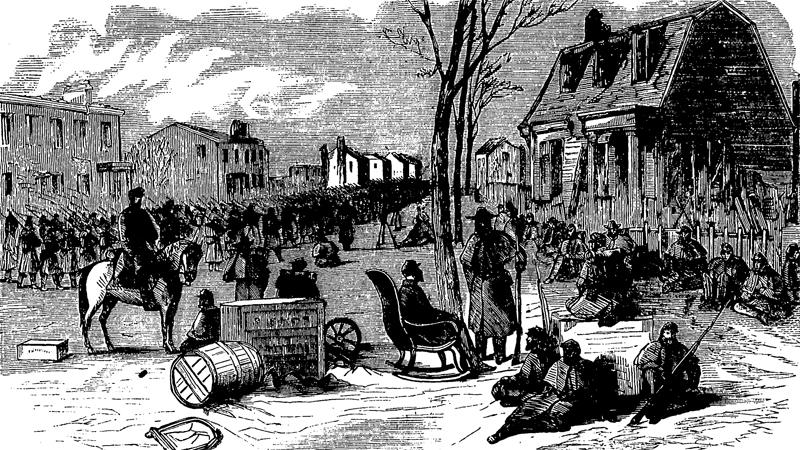

The Post’s Civil War Half-Time Report

No country can win a war if its military strength isn’t matched by the determination of its people. If a war lasts too long, the public’s resolve runs out before the ammunition does. Case in point: it would have been extremely difficult if not impossible for the administration to maintain public support for the Vietnam War for its entire 14 years. More recently, our country’s determination has been challenged by 11 years in Afghanistan that have produced no decisive victories.

It was no easier 150 years ago, when the Union Army was still recovering from its December 1862 defeat at Fredericksburg. A growing number of Americans were demanding that President Lincoln negotiate with the Confederate government.

In this winter of discontent, the Post responded to the “gloom and dissatisfaction which secessionists are striving to spread over the land” by comparing the achievements of the Northern and Southern armies. In “What We Have Done and What the Rebels Have Done” (February 14, 1863), the editors credited the Union with 33 victories and the Confederacy with just 17.

This ratio of battlefield successes—nearly two-to-one—gives the impression the Union Army was outfighting its Confederate counterpart. But, if truth be told, Post editors were fiddling with the numbers for reasons that were hardly journalistic. The publication had an agenda to stir up waning enthusiasm for Lincoln’s war efforts.

There had been plenty of support for the war when it began in March 1861. Young men throughout the North rushed to enlist, their only worry being the war would be over before they had a chance to prove themselves. After all, they presumed, this would be a short, decisive war.

Then the long list of Union defeats began. In July 1861, the Confederates defeated General McDowell at Bull Run. In March 1862, they defeated General McClellan on the Virginia Peninsula. In August, they defeated General Pope, again at Bull Run. In December, they threw back General Burnsides at the battle of Fredericksburg.

The only place where the Union seemed to advance was in the western states, where Ulysses Grant was making a name for himself with a string of river victories. But Kentucky and Tennessee were a long way from Richmond, Virginia, the seeming invulnerable Confederate capital.

So Post editors rewrote the war to put the Union Army and Navy in a more positive light, using standards that consistently favored the North. For example:

• Three of the Union “victories” were not achieved by combat but reflected territories fell into Federal hands after the Confederates abandoned them.

• The “Evacuation of Manassas” was, in fact, a retreat.

• Two of the Confederates’ major wins at Bull Run were listed as just one victory.

• The editors counted five Union victories in the Peninsula Campaign, but gave the Confederates just one for winning the entire campaign. Moreover, everything the Union gained at Yorktown, Williamsburg, Hanover Courthouse, Fair Oaks, and Malvern Hill, they lost when driven from these battlefields as they retreated down the peninsula.

• Overall, the editors also didn’t weigh the Union and Rebel successes on the same scale: the South’s victories at Bull Run, the Virginia Peninsula, and Fredericksburg were a greater feat of arms than the minor battle of Drainesville or Mill Spring, but reading the Post article, you’d never know that.

Southerners would have recognized the true disparity in the two armies’ successes. They knew that, for all the North’s small victories, the South had kept them from advancing into Virginia for two years. What they couldn’t see in 1863 was how these little victories were quietly adding up and reducing their ability to wage war. The Confederacy still put its faith in winning with a decisive victory in one, big battle. It had been true in Napoleon’s day, but was no longer. Modern wars, waged across the breadth of a nation, were won by countless small wins with little glory and savage fighting.

But a campaign that relies on countless small wins, as we’ve seen in our current fighting in the Middle East, doesn’t look like progress.

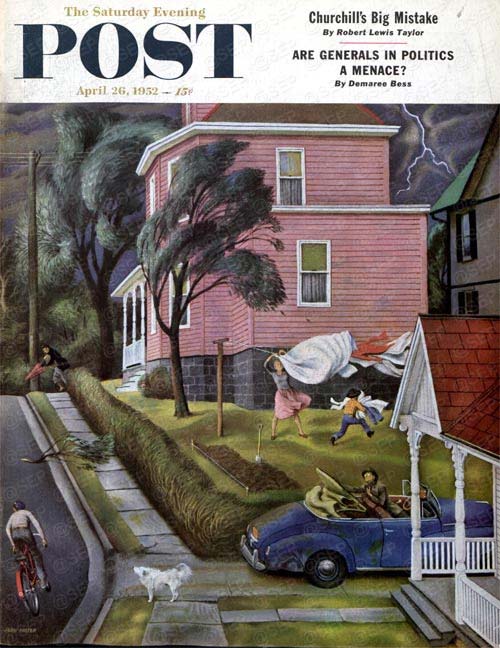

Classic Covers: At Home in the ’50s

by John Falter

April 26, 1952

In a contemporary description of this cover, Post editors wrote that artist John Falter remembered well the spring storms from his Midwestern childhood in Nebraska and the way trees turned up the undersides of their leaves and looked like phantoms.

His more than 125 Post covers depicted everyday life, and often its foibles. (See “John Falter’s August.”)

Falter was known for his masterful use of outdoor light, reflected here with quickly disappearing patches of light and just as rapidly darkening skies.

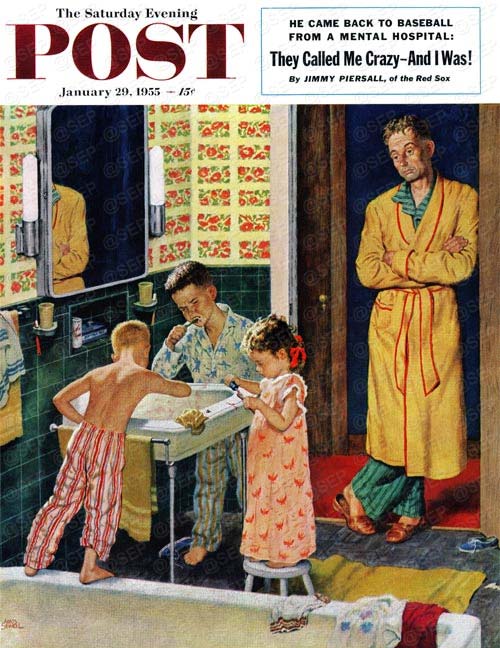

by Amos Sewell

January 29, 1955

According to a 1938 article in the Post, San Francisco-born artist Amos Sewell worked at a bank for several years, studying art in the evenings and spending vacations sketching up and down the Pacific coast. Then “in 1931, right in the middle of the depression, (Sewell) decided he was tired of the banking business and shipped out as a work-a-way on a lumber boat bound for New York, via the Panama Canal.”

In spite of his earlier vagabond lifestyle, many of Sewell’s 45 covers are notable for their homespun quality. Prime examples include this 1955 suburban toothbrushing scene, a father assembling a swing set (see “Thanks, Dad!”), and a little boy playing cowboy (see “Romance of the Cowboy”).

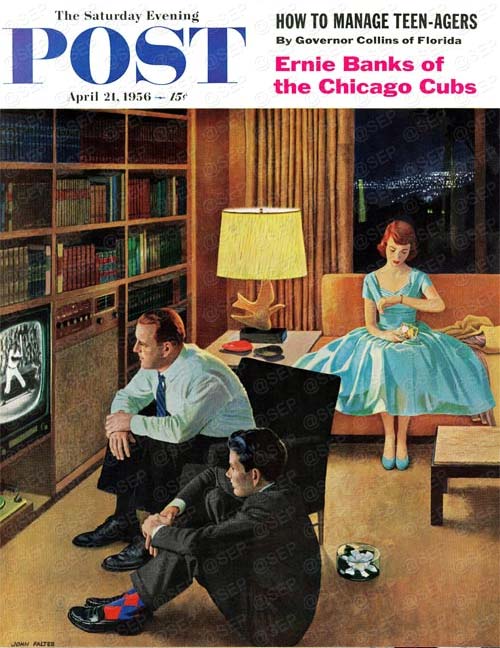

by John Falter

April 21, 1956

It all says mid-1950s: the TV, the dress, the lamp, the ashtrays… we have everything but tailfins here in this portrait of teenage angst.

The urbane setting (note the glittering city lights in the window) seems far removed from John Falter’s corn-fed Nebraskan boyhood. But let us be reminded of the artist’s meticulously rendered cityscapes as featured in “Can You Guess the City?”.

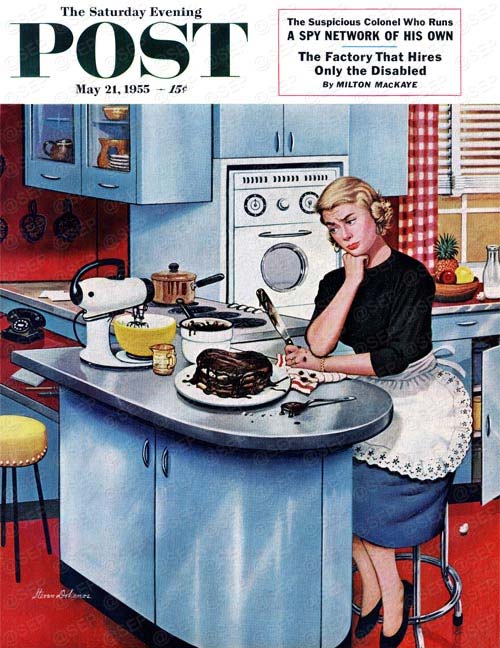

by Stevan Dohanos

May 21, 1955

Adept at drawing humor from everyday life, Stevan Dohanos’ covers include a toddler in a bedroom happily emptying purses as grown-ups gather in the next room and a woman “on vacation” at a beach cabin. (See “The Great Covers of Stevan Dohanos.”)

About this 1955 kitchen scene, Post editors wrote: “These newfangled kitchens certainly have helpful equipment, such as wall ovens with windows so one can watch a cake fall.”

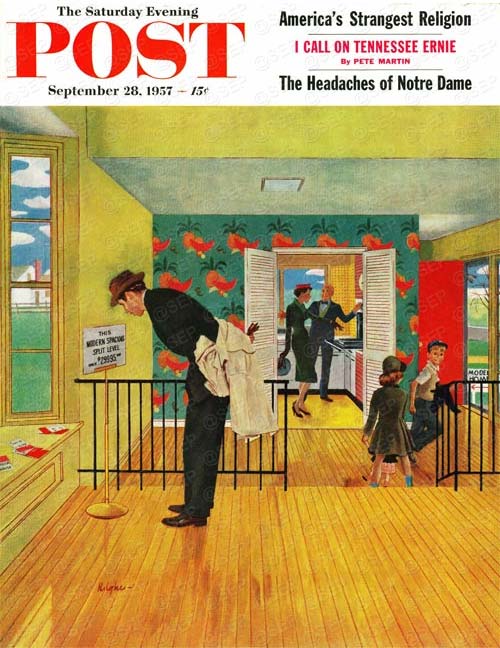

by George Hughes

September 28, 1957

Artist George Hughes favored vibrant colors and upper-middle class settings. Because the family is fashionably attired, we might assume some level of affluence. Even so, the average home was around $18,000 in 1950, and the sign in this model home states: “This modern spacious split level: $29,995.00.” No question that the family breadwinner is feeling a degree of sticker shock.

On the inside cover of this issue, Post editors quipped that Hughes himself had just purchased a new, one-level home in Vermont “because he is too old a man to climb steps.” Hughes would have been in his 50s at this time, but this sort of teasing banter was typical of the artist/editor relationship.

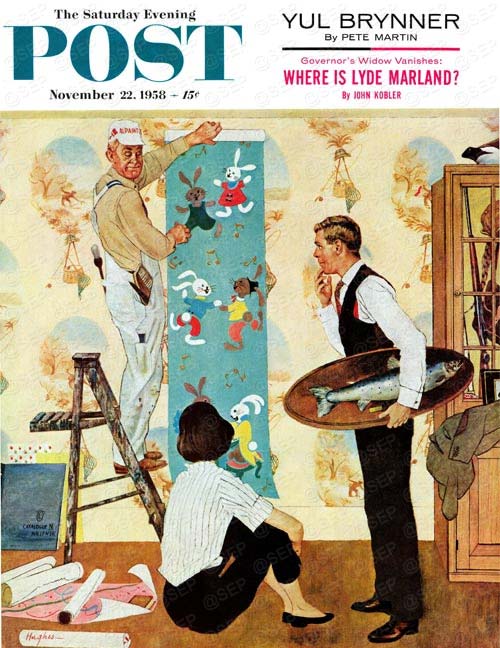

by George Hughes

November 22, 1958

Post editors wrote that the wallpaper with whitewater fishing scenes in Dad’s den is going, and he would soon be a “displaced person.” As the father of two young girls, illustrator George Hughes could certainly identify with turning man caves into kid’s rooms.

Renovation may have also been on his mind because the artist had recently moved from New York City to Arlington, Vermont, in part, to be near other Post artists like Norman Rockwell and Mead Schaeffer.

The country air must have suited Hughes, as the ’50s saw 80 George Hughes covers, making him the most prolific Post artist of the decade. By comparison, other prominent cover illustrators like Richard Sargent and John Falter did 35 and 60 covers, respectively (Rockwell did 45).

Reprints are available at Art.com.

Classic Covers: Keeping Up with Yard Work

“Gardening requires lots of water — most of it in the form of perspiration,” said author Lou Erickson, and our Post covers prove it. Some people are downright persnickety in the care of their lawns and gardens while others are content to let Mother Nature take her course.

Definitely the odd couple. Mr. Felix is fastidious to the point where we believe the blades of grass salute as he walks by. Note how even the flowers stand at attention. But he isn’t all uptight: He is, after all, keeping up with the baseball game on his handy black and white TV while working. But in the July, 1961 cover by artist John Falter, Mr. Oscar next door is taking it easy, not at all bothered by overgrown hedges and toys on the sidewalk. Well, he probably had a hard week at work. Obviously, his dog did, too.

I'd Rather Be Golfing

May 20, 1961

On the other side of town, two equally fastidious neighbors are flummoxed—yes, that’s the word, flummoxed. In the May 20, 1961, cover by Thornton Utz, the lawn slaves work with push mowers and rakes while the guy from number 319 spends his Saturday as he darn well pleases, which includes lighting up a big cigar and taking his golf clubs for a walk, with nary a backward glance at his overgrown lawn.

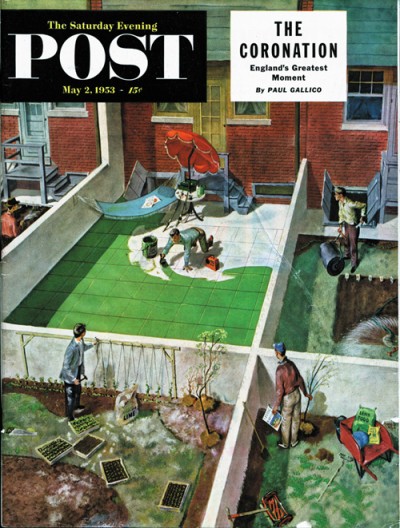

Painting the Padio Green

May 2, 1953

There’s more than one way to green up a lawn. In Utz’s May 2, 1953, cover, one man simply laid concrete and painted it green—and flummoxed neighbors appear once again. As the 1953 Post editors observed, “What sound-minded man would rest in a hammock when he can sprain his muscles spading the sweet earth?” Sound-minded or not, we have to give the guy points for ingenuity.

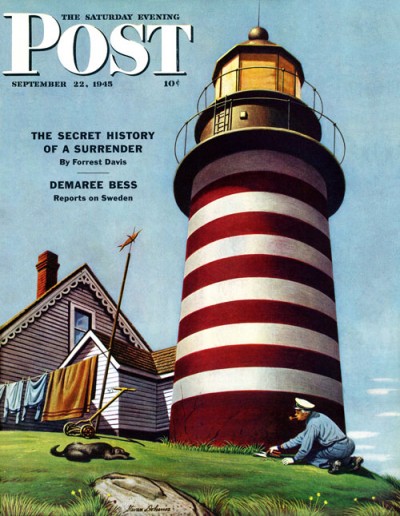

It isn’t only private lawns that need tending. Stevan Dohanos’ 1945 lighthouse, bold in red and white stripes, includes a busy groundskeeper neatly trimming the weeds, with no help whatsoever from the lazy pooch nearby.

Lighthouse Keeper

9/22/1945

Fond of finding gardens in unusual spots, Dohanos also painted the August 9, 1947, cover depicting three railroad workers watering a flower bed with the train looming right behind them—a cover to please both gardeners and train buffs alike.

Possibly the oddest spot for a garden was found by artist John Atherton. In a junkyard in Pittsburgh, no less, amid heaps of rusty scrap iron, the derrick operator planted a small garden. The enterprising man even made a fence around his plot using strips of scrap iron. “Gardens are a form of autobiography,” said Sydney Eddison, highly acclaimed gardening author and teacher, so it says much about the man that he seeks beauty amid the unsightly.

City Park

June 5, 1954

In Falter’s June 5, 1954, cover, as a man tends a downtown plot of flowers, his territory seems to be invaded by a spaceman after his baseball. Okay, some covers are just hard to explain—you’ll have to click on it and see for yourself. The older couple in Stevan Dohanos’ May 26, 1951, cover do the watering. Well, at least he is, and we must say that’s a lot of garden to water with a hose. When Post editors asked Dohanos, “What ate some of the lettuce and radishes in your picture—rabbits?” the artist replied, “Certainly not. People. No pests in my gardens. They don’t like the smell of paint.” Well, we warned you that artists are an odd lot.

Gallery

Lighthouse Keeper

9/22/1945

Tidy and Sloppy Neighbors

July 1, 1961

I’d Rather Be Golfing

May 20, 1961

Painting the Padio Green

May 2, 1953

Lemonade for the Lawnboy

May 14, 1955

City Park

June 5, 1954

Trainyard Flower Garden

August 9, 1947

Spring Yardwork

May 18, 1957