Rockwell Video Minute: Elect Casey

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: (Norman Rockwell / © SEPS)

The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

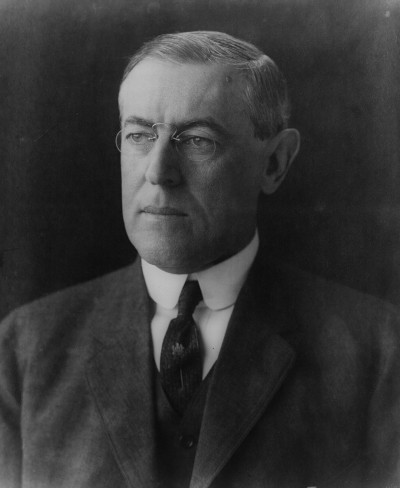

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

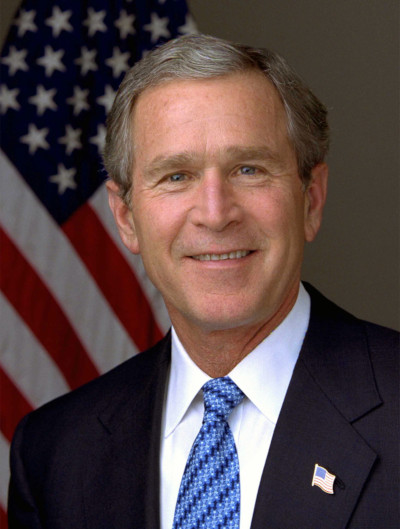

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

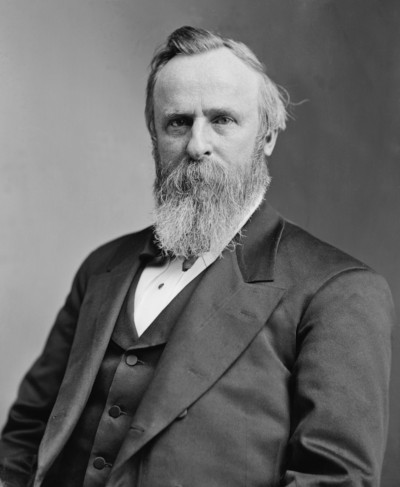

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

How Nebraska Farmer Luna Kellie Was Radicalized Before the 1896 Election

In the late 1800s, one Nebraska farmer was beleaguered by an unruly farm, ten children, corrupt bankers, and indifferent politicians. She could have given up. But instead, Luna Kellie did something about it.

For most members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, a political advocacy group, the work of organizing occurred solely during the Alliances’ meetings and events. Yet for Luna Kellie, the Alliance’s secretary, the work often continued until the wee hours of the morning. As she later wrote in her memoirs, “if I had extra time when others were asleep, I would devote it to writings for the papers.” Kellie’s work for the Farmers’ Alliance eventually drove her to become a leader in the larger populist movement that swept through the U.S. during the 1890s. Yet even as she took on more responsibility, her political life and home life continued to intersect in the same way they had during those late night writing sessions. While Luna Kellie is far from being the most famous of the populist leaders, hers is the story of a woman driven to political action by personal hardship, making it particularly emblematic of the American political climate in the lead up to the pivotal 1896 presidential election.

St. Louis was a crowded town in 1876, and both Kellie and her husband J.T. felt that their dream for a safe and prosperous life was becoming more and more improbable in the industrializing city. So when the couple read a railroad advertisement for cheap homestead mortgages in Nebraska, they jumped at the opportunity. As Kellie wrote, “It seemed to me a great chance to see a beautiful country like the pictures showed and have lots of thrilling adventures.” A new life on the prairie also carried with it the promise of financial stability, a safe home, and a happy family. But in reality, Kellie’s new life was anything but the Little House on the Prairie. Instead, the newly Nebraskan farmer found that her farm’s success and her family’s well-being were at the whims of railroad magnates, cutthroat capitalists, and financiers in faraway states.

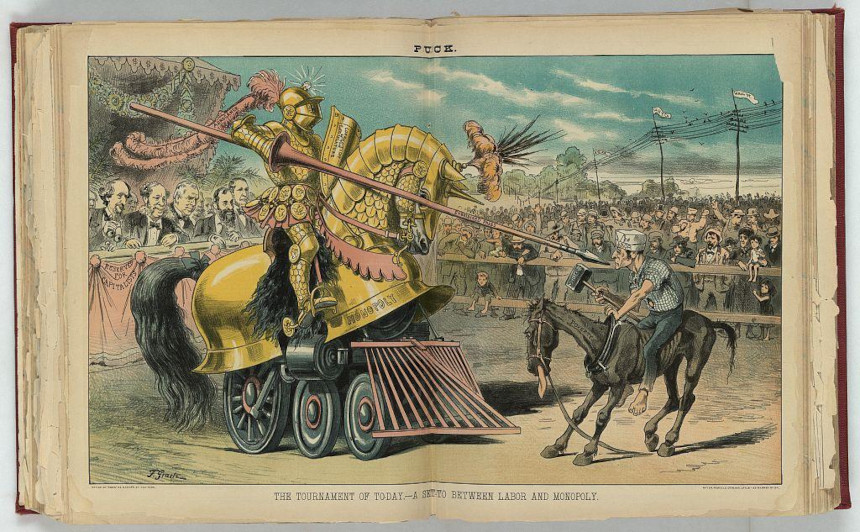

The decades after the Civil War promised a better life. Yet while the end of the 19th century was a time of widespread expansion, it was a time of even more widespread corruption. For freed African Americans, this corruption came in the form of Jim Crow regimes and new systems of oppression. For immigrants, it was political machines and decaying slums. For farmers — such as Kellie — corruption was apparent in the practices of railroads and banks that jockeyed for economic dominance over the vast expanses of the America west.

The end of the 19th century is called the Gilded Age on account of the decadence exhibited by urban capitalists such as Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, yet this same monopolistic impulse extended across the country. Kellie was quick to point out how such corruption was at play in Nebraska, writing that

even after they [the railroads] had made 4 times the necessary ‘expenses’ had they [only] been content with a profit of 1 million a month instead of 2. If they knowing the farmers were raising their stuff for them below cost of production had said we will divide the profit on each haul of wheat and corn each carload of stock with you we would not only [have] been enabled to keep our place and thousands more like us but would have been enabled to live in comfort and out of debt.

One bad harvest was all that stood between most farmers and financial ruin, a fact that hung like a shadow over Kellie and her family. Midwestern homesteads were plagued by environmental hazards, ranging from crop-eating grasshoppers to tornadoes and disease. Kellie experienced all of these trials, with the extra challenge of raising ten children at the same time. Additionally, the mortgage on Kellie’s homestead was handled by an apathetic bank in distant Boston. As the bank continued to raise interest rates, Kellie and her family faced the very real possibility of losing their land entirely. To combat this fear, she began selling vegetables in nearby towns as a source of supplementary income, yet she knew that quick cash was not enough to remedy the challenges her family faced. She had realized that her failure to find success and happiness in Nebraska was the result of an economic system that disempowered prairie farmers for the betterment of railroads, banks, and the bottom line. And so Kellie turned her energy towards organizing.

Farmers around the country were beginning to identify the systematic roots of their poverty (including Kansas farmers who eventually brought their issue to the House of Representatives). However, both major parties were controlled by northern industrialists who had no inclination to support homesteaders. As a result, the populist movement emerged in different pockets throughout the country, eventually coalescing as a third-party option to fight for the livelihood of farmers.

Though it may not have been clear at the time, Kellie was at the forefront of the populist movement in Nebraska. Both she and J.T. were members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, an organization that held town hall meetings and created literature that offered Nebraska homesteaders a voice in national politics. However, Kellie insisted that “the alliance at this time was not supposed to be political.” Instead, it was simply defending the work and lives of prairie farmers.

Still, Kellie continued to become more involved (much more than her husband) in the Farmers’ Alliance. She was elected as the organization’s secretary and took on the job of editing the Alliance’s newspaper, The Prairie Populist. In the paper, Kellie published biting condemnations of the railroads, bankers, and economic practices that had caused her family so much hardship. Her political awakening also extended beyond the needs of farmers. Kellie’s agency in the Farmers’ Alliance made her increasingly adamant about the need for women’s suffrage, and she soon took on the additional task of traveling to conventions around the country to fight for the vote. As The Scranton Tribune noted of one of her speeches, she “exerted her influence in favor of universal suffrage, undaunted by the fact that she was obliged to carry her baby with her during the long journey.” Kellie took on all of these new responsibilities while continuing to work on the homestead and raise her children, a feat that only strengthened the intensity of her political engagement.

As she traveled, Kellie earned a reputation for her fiery speeches. She was a songster, a type of public speaker who wrote political lyrics to well-known folksongs and would intersperse bits of verse throughout addresses. Luna traveled throughout Nebraska and its bordering states, engaging audiences of like-minded farmers with her urgent, song-infused speeches. The most notable of Kellie’s addresses was her “Stand Up for Nebraska” speech, which featured passionate lyrics about the deplorable practices of business monopolies and the financial security that Nebraska’s land should have provided:

Stand up for Nebraska! and shame upon those

Who fear the extent of their steals to disclose.

Who say that she cannot grow wealth or create;

But must coax foreign capital into the state.

Such insults each friend of the state deeply grieves:

Stand up for Nebraska and banish her thieves.

Through the Farmers’ Alliance, Kellie found her political voice to speak against the “foreign capital” of railroad companies and the larger wealth gap that was present throughout the United States. However, as the populist movement ballooned into a national third party, Kellie was quick to realize that the local roots and honest message of the Farmers’ Alliance was being corrupted. In the lead-up to the 1896 presidential election, the wildly successful populist candidate William Jennings Bryan agreed to combine forces with the Democratic Party and run as their candidate. So-called “fusionists” were in favor of this decision. People like Kellie, who believed that the populist movement’s central mission of helping farmers was being betrayed, did not.

Kellie continued organizing for the Farmers’ Alliance, but her premonitions were partly realized. Bryan lost the 1896 presidential election, and soon thereafter the Populist Party lost steam. It was perhaps the movement’s only chance at success on a national scale, and it was squandered. The community organizing that was the bread and butter of the populist movement faded into obscurity, and soon enough the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance also disbanded. Kellie continued speaking at conventions and fighting for women’s suffrage, but her political fervor waned.

Kellie continued working on her homestead, and many years later wrote a memoir for her family (which has since been published and serves as the principal source for this article). Quite poetically, she scribed the story of her life on the back of unused Farmers’ Alliance certificates. In its closing pages, Kellie offers a disillusioned soliloquy to the results of her political work. She writes, “And so I never vote [and] did not for years hardly look at a political paper. I feel that nothing is likely to be done to benefit the farming class in my lifetime. So I busy myself with my garden and chickens and have given up all hope of making the world any better.”

It is a heartbreaking sentiment coming from a woman who contributed so much to the populist movement, yet even Kellie’s own words might fail to capture the full scope of her impact. Luna Kellie’s goal was never to have a career in politics; still, she found widespread acclaim as a speaker, writer, and organizer. She was driven to politics by personal hardships, and even though the main cause she fought for may not have found success, she did succeed at giving a voice to the great number of people who faced problems similar to hers.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The Greatest Political Comeback in American History

Featured image: Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge (Library of Congress)

Rockwell Video Minute: Arguing Politics Over Breakfast

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

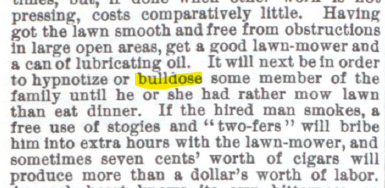

In a Word: The Racist Origins of ‘Bulldozer’

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When you see the word bulldozer, you might conjure an image of a large yellow machine with caterpillar treads flattening everything before it with its steel-toothed blade. Or maybe your mind goes back to a smaller Tonka version of this mechanical behemoth that you played with as a child. Taken on its own, with no context, bulldozer might even call to mind some serene bovine scene, perhaps Ferdinand the Bull dozing among the daisies.

How jarring, then, to discover bulldozer’s horrible, violent beginnings.

Bulldozer (originally spelled bulldoser) first appeared in the run-up to the election of 1876. That was the final year of President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term in office, and he had unexpectedly declined to run for a third term. In his place, the Republican party put its support behind Ohio Governor and former U.S. Representative Rutherford B. Hayes, while the Democratic candidate was New York Governor Samuel Tilden.

This was an important election. All the former Confederate states had returned to the Union, post-Civil War Reconstruction was ongoing, and this was the first presidential election in which African-American men could vote for someone who wasn’t Ulysses S. Grant. The outcome of the election of 1876 would shape the future of the South for years to come.

The former slave owners and secessionists in the South knew it, and they weren’t about to sit back and let the North and their former slaves usurp their power and privilege. Despite three new federal laws in 1870 and ’71 designed to protect Black Americans from violence and coercion at the polls, many were bulldosed into silence. Bulldose was a slang term derived from either “a dose fit for a bull” or “a dose of the bull” — the second being a reference to the bullwhip. Bulldosers used physical violence against Black voters either to keep them from the polls or to intimidate them into voting Democratic.

Going into the election, in five states — Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina — a majority of registered voters were African American. One would expect, in a fair election, that the Republican candidate would easily take these states. But after the votes were tallied, Tilden had won the popular vote in Alabama and Mississippi.

The results in the other three states were even more unexpected. After counting had finished, both parties claimed victory in those states. On election night, Tilden was the presumed winner with 184 electoral votes, 19 votes ahead of Hayes and 1 vote away from holding a majority.

The 20 electoral votes of these states (plus Oregon) remained undecided for months as first the two parties and then the two houses of Congress launched separate investigations. Democrats and the Democratic-controlled House committee accused the Republicans of ballot stuffing and coercion. Republicans and the Republican-controlled Senate committee accused the Democrats of the same.

In the end, the presidential election was decided behind closed doors. In what came to be called the Compromise of 1877, the Democrats conceded the remaining electoral votes to the Republicans, making Rutherford Hayes our 19th president, but in return, federal troops were to be removed from the South, essentially ending Reconstruction and returning power to the same men who had controlled the South during the Civil War.

Though violent intimidation at the polls certainly continued, Southern officials found new ways to suppress the Black vote, including Jim Crow laws and grandfather clauses. Bulldosing took on the wider meaning of “to coerce or restrain by use of force,” and it was ripe for a more literal use when large, seemingly unstoppable machines came on the scene.

The machine we think of as a bulldozer was invented in the early 1920s, and by the initial months of the Great Depression, we start to find the term bulldozer in writing, with that Z further obscuring the word’s origins. The violent, racist origin of bulldozer is one reason many people now use the term earth mover to describe these massive machines.

If you’d like to learn more about the election of 1876 — including commentary from the Post while the election results were in flux — read “The Worst Presidential Election in U.S. History.”

Featured image: Andrey Yurlov / Shutterstock

75 Years Ago: FDR Announces His Run for a Fourth Term

“There are only three certainties in this world,” as the saying used to go, “death, taxes, and Roosevelt.” On July 11, 1944, Franklin Delano Roosevelt further solidified this idiom by becoming the first — and only — U.S. president to announce he would seek a fourth term in office.

In the midst of World War II, Roosevelt decided the country would be best be served with consistency in the executive branch. Unlike in 1940 when he did not openly campaign for re-election, and allowed himself to be drafted at the Democratic Convention, the President declared that he would seek an unprecedented fourth term in the 1944 election.

At the time, The Saturday Evening Post was skeptical of Roosevelt’s performance, calling the New Deal “dictatorial, inept and bumble-puppyish” and his foreign relations puzzling. In a July 22, 1944, editorial that appeared after Roosevelt made his announcement, the Post was particularly critical of Americans’ support of FDR’s foreign policy: “Where, the goggle-eyed voters will be asked, can you find a Republican qualified to chat about matters of state beside Winston Churchill’s bathtub?”

But the Post’s disfavor couldn’t stop the Roosevelt campaign. In selecting a vice president, Roosevelt favored his then VP, Henry A. Wallace, to continue on the ticket in 1944, but when the conservative members of his party objected to Wallace, Roosevelt leaned toward James Byrnes instead. When the more liberal wing of the party objected to Byrnes, Roosevelt chose the middle-of-the-road option, Missouri Senator Harry S. Truman.

Roosevelt would go on to win the presidency; however, he would not finish his term. He succumbed to cerebral hemorrhage in April of 1945, leaving the rest of his term, and the end of the Second World War, to President Truman.

On February 27, 1951, the states would ratify the 22nd Amendment, thereby enshrining in law that presidents could serve only two terms. The Amendment guaranteed Roosevelt’s legacy as the longest serving president in American history.

Featured image: The Life of Franklin D Roosevelt, Archives New Zealand r the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license / Wikimedia Commons

Big Money and Women Voters: Who Really Chooses the President?

Remember when Washington was running out of money? Just last year, Congress was threatening to shut down the government because no one could find $1.3 Billion needed to meet the annual budget.

Well, those days are gone, we’re glad to report. A fresh breeze is blowing money into town—about $6 Billion’s worth. That’s the amount that will be spent on this year’s elections.

But what will they get for that $6 Billion, beside mountains of flyers and hours of TV ads? Will it change the outcome of a presidential election?

No one can tell for certain. But back in 1948, George Gallup was convinced presidential campaigns didn’t change voters’ choices.

In a very real sense, presidential elections are over before they begin.

They are decided to a great extent by events that have occurred in the entire period between two presidential elections, rather than by the campaign.

In politics it is always later than you think.

Gallup had polled voters before and after the presidential elections of 1940 and 1944. He found very few voters switched their choice of candidates between June and November.

Of course, it would be foolish to claim that campaigns have no effect or change no votes. But they appear to have less effect and to change fewer votes than the average party leader would like to think.

Voters listen to campaigns pretty largely to confirm what they already think.

[Yet] in presidential races today, everything is made to depend on the campaign—as if the voters lived in a mental vacuum for three and a half years, and only snapped out of it between June and November of the fourth year.

The ineffectiveness of presidential campaigns prompted Gallup to ponder—

Is this wise—this pitching of all effort and money into a campaign and then coasting along for four years?

Perhaps all the hullabaloo, the verbal blasts and counterblasts, the rallies, parades, blaring of bands, kissing of babies, the feverish rushing about of stump speakers and the millions of dollars spent are not entirely necessary.

[Could] a political party give up campaigning and win? Probably not. Some kind of campaign would be needed to keep in line the voting intentions of those who do make up their minds early.

Perhaps political leaders could profitably spend more time trying to increase public acceptance of their party between elections.

Is this still true today? Will those billions of dollars and hours of politicking ultimately change no one’s mind in the 2012 presidential election?

One recent study indicates that presidential advertisements could persuade voters, but did little to inform or motivate them to vote. Another study found that campaigns could influence voters “but the nature of this influence appears to be rather complex”—a meager return for such a high cost.

Gallup’s 1948 article— “Do Campaigns Really Change Votes?” — challenged several assumptions cherished by politicians. Party platforms, for example, were useless (“most people don’t read them”) and political speeches had almost no impact on voters (“n the course of thirteen years of polling, covering more than 190 state, local, and national elections, we have found little evidence that one speech or even a series of speeches changes many votes”).

He also made this claim:

Don’t worry too much about the women’s vote or “how to win the women over.”

They don’t vote in a bloc and they don’t vote any differently from men.

The division of sentiment among women is almost identical with that among men. Rarely in recent years has it amounted to more than two percentage points. There does not appear to be any such thing as the woman’s viewpoint in politics as distinguished from the male viewpoint when it comes right down to voting on Election Day.

That may have been true in the 1940s, but the granddaughters of those women voters are showing far greater independence in their choice. The “gender gap” has become significant. In 2008, Barack Obama received 49% of his votes from men and 56% from women. Interestingly, 55% of the votes for George W. Bush came from men, 48% from women—again, a 7% difference.

The gap reached 10% in 2000 (43% of women, 53% of men voted for Bush), and in 1996, the difference between men and women voting for Bill Clinton was 11%.

When the gender gap was just 2%, Gallup made several conclusions that—we hasten to add—might have been valid for their time.

Men and women, dissimilar biologically and to some extent emotionally, tend to think almost exactly alike politically.

The reason seems to be that, on political matters, women generally accept the judgment of their men-folk. They take their cue from the opinions or prejudices of a husband, a father, a son or other male member of the family. Of course, this is not true of all women. But in the average household the woman goes on the theory that her man knows more about those things than she does.

This is 1948, remember.

Polls have found that when a change of political sentiment takes place, it almost always starts with the men, not the women. The women catch up with the trend later—after they’ve talked to the boss.

In all fairness, it should be said that there is no real reason why women should vote differently from men, even if they paid no attention to the ideas of the allegedly dominant male. No one would argue that women ought to vote differently just for the sake of being different. The only point here is that one must be cautious in talking about the woman’s viewpoint in politics. Although the average male candidate running for office usually makes quite an effort to win the feminine vote, it may be questioned whether such pains are necessary. If the male voters can be won over, the women will generally come along too.

Presumably, some of those billions of dollars are being spent right now to understand just why women don’t vote the same as men.