The Role of Dreams in Human Survival

The contents of our dreams have been the subject of study and speculation for as long as humans have slept all over the earth. In Homer’s Iliad, a dream is personified as a messenger sent from Zeus to tell Agamemnon to attack the city of Troy. Shakespeare mused on the possibility of dreams in the afterlife: “in that sleep of death what dreams may come when we have shuffled off this mortal coil, must give us pause.” Freud’s best guess was that our dreams are full of metaphors for penises.

Since dreaming is such a universal human experience, we’ve long figured these nightly hallucinations must have some sort of meaning or utility. The serious study of dreams, or oneirology, is a relatively new field that offers new insights each year for why we dream. Phallic symbols seem to have little to do with it, but some new research is pointing toward our own survival as a reason for dreaming.

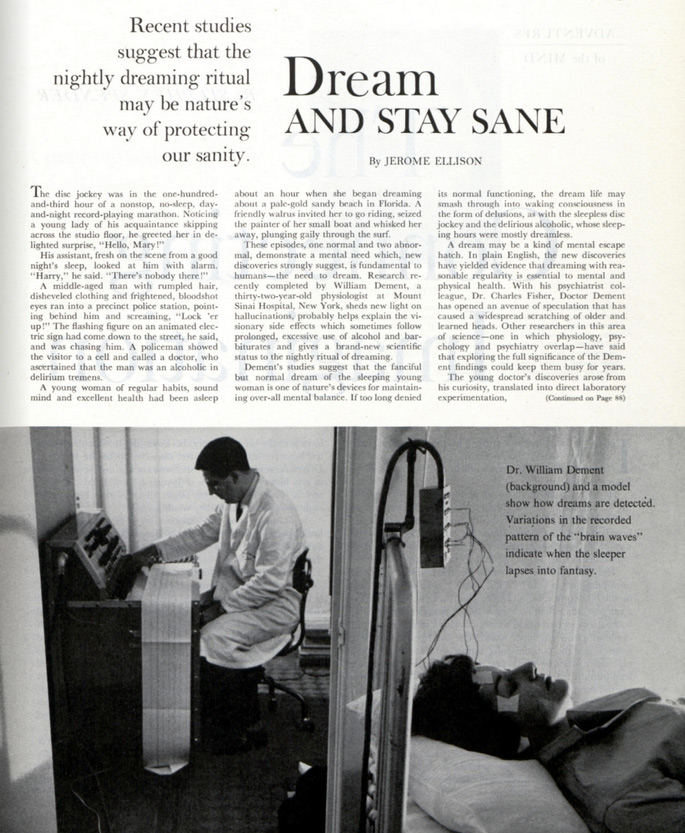

The beginning of the scientific study of dreams can be pinned to the discovery of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) cycles by Nathaniel Kleitman and Eugene Aserinsky in the early 1950s. The Saturday Evening Post focused on the findings of their colleague, William Dement, in a 1961 article called “Dream and Stay Sane.” Dement’s studies asked the important question of “whether a substantial amount of dreaming is in some way a necessary and vital part of our existence.” Dement and his colleagues theorized that the hallucinatory nature of dreams gave the mind a sort of recess each night that could protect it from insanity during the day.

Dr. Joseph De Koninck, emeritus professor of psychology at University of Ottawa, has been studying dreams for much of his career, and he says we’ve come a long way since those early days. While the distinction between the necessity of dreaming and the necessity of REM sleep still remains unclear, studies have since observed dreaming — although it is less common and typically less vivid — in non-REM sleep. A particularly impactful discovery, De Koninck says, was the realization that the frontal lobe is at rest during dreams while other parts of the brain like the amygdala are active. Because the frontal lobe is responsible for functions like judgment and mathematics and the amygdala houses emotions — especially fear — this explains why we find it difficult to plan or think critically in dreams yet experience emotions like joy and fear in abundance.

Those bouts of ecstasy and terror in our sleeping hours could be serving specific functions.

De Koninck was involved in one study, published last year in Consciousness and Cognition, that tested part of a theory of why we have bad dreams, the Threat Simulation Theory. The TST posits that “the function of the virtual reality of dreams is to produce a simulation of threatening events, the sources of which are derived from situations experienced while awake and associated with a strong negative emotional charge.”

The TST was developed in 2000 by Finnish cognitive neuroscientist Antti Revonsuo to give a biological explanation for nightmares. He proposed that our ancestors’ brains adapted to simulate real-life threats in our dreams so that we would be prepared to cope with such dangers in waking life. The 2018 study shows that threat simulation in dreams is more active in traumatized individuals and can even be activated by threatening events and high stress levels in a day preceding a dream.

The theory that our dreams might exist to simulate real-world events as a purposeful function accounts for more than the nightmares. The Social Simulation Theory (SST) is a similar psychological model that looks at social interactions in dreams, from the friendly to the aggressive to the sexual. If dangerous situations in dreams exist to prepare us for such threats in the world, then perhaps the many social encounters we dream up could be adaptive measures to aid our interactions as social beings.

De Koninck points to “Social contents in dreams: An empirical test of the Social Simulation Theory,” forthcoming in Consciousness and Cognition, as the latest example of this sort of research. Previous studies — going as far back as the ’60s — have found that real-world isolation can actually increase the amount of social content in dreams. The 2019 study confirms this, showing the social contents of dreams to be greater than those in concurrent waking life in its participants. It did not back up another tenet of the SST, however, that “dreams selectively choos[e] emotionally close persons as training partners for positive interactions.” In this study, participants’ dream characters were more random than had been observed in past studies.

When I spoke with De Koninck, I shared with him a dream I experienced the previous night that contained both a social and a threatening scenario. In it, I arrived in Juneau, Alaska to attend a distant acquaintance’s wedding and bumped into Dame Judi Dench. We each smoked a cigarette and she expressed her annoyance at the tourists surrounding us. I was too starstruck to say much. Later on, I was in a convenience store when an armed robbery took place. As the assailant approached me, gun drawn, I reached into a cooler and grabbed a can of soda before cowering on the ground.

Did I fail the simulation? I don’t even drink soda.

Perhaps, but the important thing, according to De Koninck and others, like author Alice Robb, is that I actively shared my dream. As inconsequential and boring as they can seem, dreams have proven to be helpful when shared or recorded. In a 1996 experiment, women who were going through divorces experienced positive self-esteem and insight changes after taking part in dream interpretation groups. De Koninck says “Dreams can be a source of self-knowledge that have adaptive value. Keeping a dream journal or sharing your dreams can help you to know yourself better or better adapt to situations.” But this doesn’t mean you should panic over a particularly weird or violent dream. He refers to dreaming as an “open season for the mind,” and says we should approach any interpretation open-mindedly instead of with some sort of a universal method.

What if you believe you don’t dream or — more likely — cannot remember your dreams? You are not necessarily maladaptive if you can’t remember your dreams, but there are ways to improve your dream recall. One is to simply think about dreams and dreaming more when you go to sleep and wake up (this could explain why I remembered so vividly my Alaskan romp with Judi Dench), and try to remember as much as possible when you first arise. Another is to vary the time you wake up. Since most of our dreaming happens in REM sleep, we are more likely to remember a dream if we wake during a REM cycle.

Whether our dreams are nightly firings of random artifacts of the brain or the products of important psychological evolution, they will never fail to terrify and bemuse us. In a brief time, we’ve come to embrace the “open season of the mind” and glean more from it than we could have thought possible. The future of dream research, a field that relies on new technology and mounding data, is promising.

Featured image: Ford Madox Brown: Parisina’s Sleep—Study for Head of Parisina (Wikimedia Commons)

Do Passive-Aggressive Signs Work?

You’ve seen them before, and maybe you’ve even written one (or printed it off with cute, non-threatening clipart to emphasize your good faith): the signs and notes that serve as totally casual reminders for people to behave themselves, essentially. Some are passive-aggressive (“Unattended children will be given espresso and a free puppy”), and some are just aggressive (“Since your MOTHER does not live at this office, please clean up after yourself!”).

While dining at a local establishment, I noticed a handwritten sign on the trash receptacle that read “Please be a SUPERSTAR and don’t throw our trays away!” Of course, everyone knows to avoid tossing plastic trays into the garbage at restaurants, but this sign was implying that someone had been doing just that. Is the sign-maker trying to flatter me into good behavior? I thought. But most of all I wondered: Does it work?

These signs are universally ugly stains on otherwise pleasant spaces, and the behavior advocated by most of them is common sense: watch your children, refill the copier’s paper tray, don’t piss on the toilet seat. In fact, it could be hypothesized that reminding people to do these things — and therefore suggesting that they might not otherwise do them — fosters resentment and possible retaliation. What’s a Type A personality to do?

Adamaris Mendoza is a psychotherapist and communication coach, and she’s been noticing what she calls “common sense signs” more and more. Between restaurants, bathrooms, and taxicabs, Mendoza believes these signs are so ubiquitous that people just don’t see them anymore. The passive-aggressiveness (or whimsical irony, if you like) of some sign-makers is, Mendoza says, a communication strategy similar to that of a lot of social media: capture people’s attention and convince them to do something. There is also a catharsis for the sign-maker because they’ve said their piece, even if it’s ineffective. And Mendoza believes that it probably will be, because “a sign isn’t going to change someone’s values.”

A psychological explanation for whether or not these bite-sized bits of persuasion are effective has been in the works for more than half a century. The reactance theory, proposed by Jack W. Brehm in 1966, describes the phenomenon of “an unpleasant motivational arousal that emerges when people experience a threat to or loss of their free behaviors.” Brehm and many others have studied how and why people rebel against persuasion, demands, and advice for years, and the research has been directed at safe sex and anti-smoking campaigns, political reforms, and water conservation. It can explain why Adam bit into the forbidden fruit and, possibly, why your coworker still leaves their dirty coffee mug on the counter next to your carefully crafted sign advising the opposite.

Attempts to persuade, especially if they convey a restriction on a person’s behaviors, can be met with the boomerang effect, the unintended consequence of a listener — or sign viewer — to think and do the exact opposite of what is being conveyed. This all depends on the message, of course. In a study about sun safety, when the message was framed as a loss (“When you do not use sun protection you will pay costs.”) instead of a gain (“When you use sun protection you will gain benefits.”), participants showed significantly stronger perceptions of threat to their freedom. That threat positively correlated with feelings of anger. Other studies have shown that messaging can work against itself by using controlling language (words like should, ought, must, and need) instead of less forceful terms (consider, can, could, and may). The more a message threatens people’s ability to decide how to behave, the more they are wont to ignore it.

“As a general rule, any communication that generates anger in the target person at the sender or the sender’s message is less likely to be persuasive,” says Timothy Levine, the Distinguished Professor and Chair of Communications Studies at University of Alabama-Birmingham. “It’s hard to sort out ineffective from actual backfire, but being likable is a better bet for persuasion.”

It would be difficult to argue that a sign (especially a wordy, confrontational one) stands much of a chance against our own instincts. So what are they good for? Release, perhaps. The moment of hanging a piquant, articulate message after weeks or months of annoyance, one can imagine, would be an emotional purge. But if the goal is to instill actual behavior change, psychology experts recommend that we avoid robbing people of their own sense of volition while making our requests, perhaps by implying choice. If this isn’t possible, it might not be worth making a sign at all.

I wondered about the “SUPERSTAR” sign and its maker: who were they? Did it work? Was it worth it? So I gave the restaurant a call. Many months had passed, but the employee who answered the phone remembered the sign, although it had since been taken down. He said it was created by a coworker who just liked to draw and make signs while she was bored. He didn’t even remember their having any problem with trays being thrown away. So did it work? “Yeah, maybe?” he said. “I think she just wanted to lighten the mood and create a fun atmosphere.” Basically, it wasn’t that deep.

On a recent return to the restaurant, I noticed a new handwritten sign taped next to the drink machine: “Do NOT order a water cup and fill it with soda! We WILL catch you, and we WILL embarrass you!” Although the threat of humiliation is typically a weak deterrent for me, a shameless writer, I obeyed the warning, because I am also a superstar.

Introverts, Unite! The Rise of the Hermit Economy

“There’s a great, big beautiful tomorrow… shining at the end of every day!” sings the animatronic family of Walt Disney’s “Carousel of Progress.” The rotating robot stage show premiered alongside “It’s a Small World” at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Audience members ride around scenes depicting an American family in four eras of technological innovation, and the ride culminates in the future in an electric home that affords its inhabitants leisure by performing their time-consuming chores.

Dr. Larry Rosen remembers visiting “Progressland,” the original name of the General Electric-commissioned ride, at the World’s Fair in 1964. Rosen remembers that, ironically, the visionary experience offered an optimistic glimpse of a future in which innovation would free up our time for more socialization. “The intention was always that it would do the menial tasks we didn’t need to do,” he says, “but who knew the menial tasks would be connection and communication?”

Rosen is a professor of psychology at California State University, Dominguez Hills and co-author of The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World. He says we’ve reached a point where technology is making hermitry — not human interaction — easier.

In a way, Progressland’s promise of convenience technology has come to fruition. With even the slightest smartphone savvy, you can hire out all of your pesky chores: shopping for groceries, walking the dog, washing the car, assembling furniture, waiting in line at the DMV. Running errands could become a thing of the past, for some, if current trends keep up, leaving us with tons of time for… what, exactly?

Picture it: you wake up and cook your breakfast from groceries delivered via an app like Instacart or Shipt before settling down for a long workday-from-home — as 115% more Americans have been doing since 2005. Then, a stylist — from an app like Glamsquad — makes a house call to give you a blowout and a manicure while Booster is gassing up your Subaru outside. Now you’re finally ready… to binge on an entire season of a Netflix drama and settle in with some sushi delivery — ordered through your Seamless app, of course.

“These kinds of services drive us away from face-to-face interactions,” Dr. Rosen says. “If you’re spending four to six hours each day on your phone (as we’re finding that people are) making short connections that aren’t real relationships or meaningful connections, you might be much more prone to stay inside.”

According to surveys from Rockbridge Associates, the on-demand economy grew 58 percent in 2017, with sectors like housing and food delivery more than doubling. All of these on-demand startups are marketed to ease the burdens of our busy lives, but convenience technology seems to be giving us little reason to leave the house. A sort of “hermit economy” has taken shape for those who can afford it.

Dr. Damian Sendler, a digital epidemiologist with Felnett Health Research Foundation, says the hermit economy could have long-term consequences in terms of social interaction. “Once you begin relying on this nonverbal communication of sending orders on your phone, you forget how to interact with other people,” he says. “When you do have to deal with customer service or go somewhere to get something done, you might develop anxiety and a fear of interacting with people.”

The chicken-or-the-egg question is relevant here: does increasing “APPization” of services cause reclusiveness or is it welcome technology for those already desiring a more cloistered existence?

Americans have displayed introverted behavior, at least to some extent, for centuries. Reclusiveness in America has inspirational legacy — as in Henry David Thoreau’s Walden — as well as tones of pathology and domestic terrorism in the case of Ted Kaczynski. Lately, self-proclaimed introverts have been declaring the virtues of holing up at home for their health, with scads of online articles offering “signs you might be an introvert” and an introvert Facebook page with 2.5 million followers declaring relatable maxims like “Sometimes I stay inside for an entire weekend and I regret nothing.”

Popular psychology presents introversion as the perfectly natural state of being “drained by social encounters and energized by solitary, often creative pursuits.” Instead of the conventional opinion to advise socialization at every turn, a lot has been made of the need for societal accommodation for introverts, particularly in education and the workplace.

Andrew Becks, a 33-year-old digital advertising C.O.O. from Nashville and self-proclaimed introvert, says he is emotionally drained after an entire day of being “on.” Becks says, “The last thing I want to do is interact with people sometimes. I’m a lot less stressed when I feel I can use my evenings as a kind of detox from socialization.”

Becks admittedly utilizes convenience technology often. He and his husband used the app TAKL in their recent home renovation. The platform allows users to post a job and receive proposals and prices from vendors, mostly through text interactions. He’s been a fan of online food ordering ever since it came around about a decade ago. A typical night in with friends entails getting some drinks, ordering food delivery — from the vast selection of online options — and watching TV or a movie.

“The idea of going to a nightclub or a bar just does not appeal to me, but that we can leverage technology to have people over and do more than just order a pizza is pretty cool,” he says. “It allows people to maintain friendships with like-minded people in environments that are more comfortable for them.”

Becks likes the increased accountability that comes with online ordering, and he doesn’t mind losing some human interaction day to day. In fact, he says it helps him to appreciate it more, and to be more receptive to it, when he does have meaningful connections with people.

He admits that there are drawbacks to this kind of encompassing technology though. With so many opportunities for cyber consumerism, the Nashville millennial says you could get stuck in a virtual rabbit hole where you’re beholden to an algorithm to present all of this information to you: “It helps the company’s revenue and it creates a personalized experience, but it’s a kind of vortex where the brands people interact with are controlling the experience on a scale we’ve never seen before. It’s helpful to remember that we’re interacting in an ecosystem that’s designed to extract as much money out of us as possible.”

A bump in at-home services could be a sign of the market fulfilling a need, but the line between healthy solitude and socially anxious hiding can be a fuzzy one.

In Japan, the latter has been observed as a widespread trend called hikikomori. In the last decade or so, more than half a million Japanese people, ages 15-39, have been observed to live drastically reclusive lives, spending most or all of their time in a bedroom. The hikikomori, mostly men, are thought to be traumatized by social pressures, abuse, or failure, so they have resigned themselves to a life of lying around, reading, and browsing the internet indefinitely. A leading researcher of the phenomenon said global changes in social life and family are behind hikikomori, a condition that looks a lot like an exacerbated case of Social Anxiety Disorder.

Social phobia is linked to high-income countries, according to the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. The survey found that these countries (like the U.S. and Belgium) face prevalence of Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) at rates more than three times higher than low-income countries (like Iraq or Ukraine). The United States has the highest rate of people who have experienced SAD at some point in their life at 12.1 percent, and that number is up from 5 percent in 2002.

It would be difficult to deny the connection of the rise in reported social anxiety to fundamental changes in daily communication via tech use. How the creeping transformation of the service economy enters into it is up for discussion. Dr. Sendler says aspects of the gig economy can create a superficial, unequal division of power between convenience-seekers and service providers that divides communities: “From a mental health perspective, what we see is an escalated division between people and the social problem of actually connecting with people with boundaries that we didn’t have before.”

Dr. Rosen says technology is embedded in culture, and, while an influx of digital services can create an environment for isolation, it ultimately comes down to our own willingness to salvage a tradition of community in the face of a reclusive future. “Part of going outside is that there’s always a chance to have an interaction, but many people avoid these opportunities,” Rosen says. “Social anxiety is part of a larger anxiety constellation” that he says is ubiquitous.

There is precedent for such public health interventions. Campaigns against tobacco use and bullying, as well as ones for wearing seatbelts, have shown positive results. It is likely trickier, however, to meaningfully advocate for something as nebulous as quality human interaction.

The Carousel of Progress still spins Disney visitors through its idealistic portrayal of American innovation each day. It even proclaims to be the longest-running stage show in America despite the lack of actual human beings onstage (perhaps an apt undertone for futurism). The attraction hasn’t undergone any major changes since 1994, so it currently exists in the name of nostalgia. An android family forever singing in unison about “the great, big beautiful tomorrow” increasingly feels like wishful thinking from another time.