The contents of our dreams have been the subject of study and speculation for as long as humans have slept all over the earth. In Homer’s Iliad, a dream is personified as a messenger sent from Zeus to tell Agamemnon to attack the city of Troy. Shakespeare mused on the possibility of dreams in the afterlife: “in that sleep of death what dreams may come when we have shuffled off this mortal coil, must give us pause.” Freud’s best guess was that our dreams are full of metaphors for penises.

Since dreaming is such a universal human experience, we’ve long figured these nightly hallucinations must have some sort of meaning or utility. The serious study of dreams, or oneirology, is a relatively new field that offers new insights each year for why we dream. Phallic symbols seem to have little to do with it, but some new research is pointing toward our own survival as a reason for dreaming.

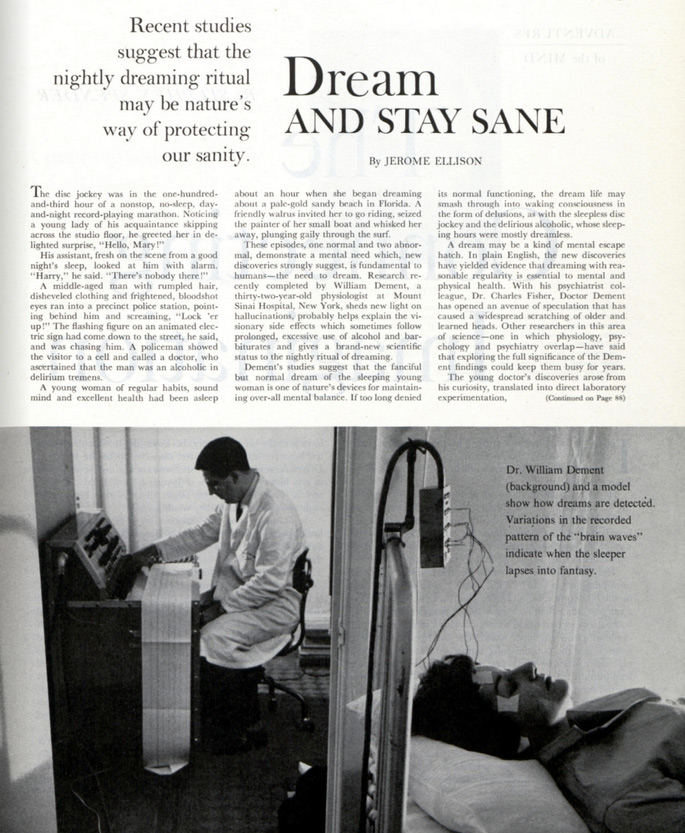

The beginning of the scientific study of dreams can be pinned to the discovery of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) cycles by Nathaniel Kleitman and Eugene Aserinsky in the early 1950s. The Saturday Evening Post focused on the findings of their colleague, William Dement, in a 1961 article called “Dream and Stay Sane.” Dement’s studies asked the important question of “whether a substantial amount of dreaming is in some way a necessary and vital part of our existence.” Dement and his colleagues theorized that the hallucinatory nature of dreams gave the mind a sort of recess each night that could protect it from insanity during the day.

Dr. Joseph De Koninck, emeritus professor of psychology at University of Ottawa, has been studying dreams for much of his career, and he says we’ve come a long way since those early days. While the distinction between the necessity of dreaming and the necessity of REM sleep still remains unclear, studies have since observed dreaming — although it is less common and typically less vivid — in non-REM sleep. A particularly impactful discovery, De Koninck says, was the realization that the frontal lobe is at rest during dreams while other parts of the brain like the amygdala are active. Because the frontal lobe is responsible for functions like judgment and mathematics and the amygdala houses emotions — especially fear — this explains why we find it difficult to plan or think critically in dreams yet experience emotions like joy and fear in abundance.

Those bouts of ecstasy and terror in our sleeping hours could be serving specific functions.

De Koninck was involved in one study, published last year in Consciousness and Cognition, that tested part of a theory of why we have bad dreams, the Threat Simulation Theory. The TST posits that “the function of the virtual reality of dreams is to produce a simulation of threatening events, the sources of which are derived from situations experienced while awake and associated with a strong negative emotional charge.”

The TST was developed in 2000 by Finnish cognitive neuroscientist Antti Revonsuo to give a biological explanation for nightmares. He proposed that our ancestors’ brains adapted to simulate real-life threats in our dreams so that we would be prepared to cope with such dangers in waking life. The 2018 study shows that threat simulation in dreams is more active in traumatized individuals and can even be activated by threatening events and high stress levels in a day preceding a dream.

The theory that our dreams might exist to simulate real-world events as a purposeful function accounts for more than the nightmares. The Social Simulation Theory (SST) is a similar psychological model that looks at social interactions in dreams, from the friendly to the aggressive to the sexual. If dangerous situations in dreams exist to prepare us for such threats in the world, then perhaps the many social encounters we dream up could be adaptive measures to aid our interactions as social beings.

De Koninck points to “Social contents in dreams: An empirical test of the Social Simulation Theory,” forthcoming in Consciousness and Cognition, as the latest example of this sort of research. Previous studies — going as far back as the ’60s — have found that real-world isolation can actually increase the amount of social content in dreams. The 2019 study confirms this, showing the social contents of dreams to be greater than those in concurrent waking life in its participants. It did not back up another tenet of the SST, however, that “dreams selectively choos[e] emotionally close persons as training partners for positive interactions.” In this study, participants’ dream characters were more random than had been observed in past studies.

When I spoke with De Koninck, I shared with him a dream I experienced the previous night that contained both a social and a threatening scenario. In it, I arrived in Juneau, Alaska to attend a distant acquaintance’s wedding and bumped into Dame Judi Dench. We each smoked a cigarette and she expressed her annoyance at the tourists surrounding us. I was too starstruck to say much. Later on, I was in a convenience store when an armed robbery took place. As the assailant approached me, gun drawn, I reached into a cooler and grabbed a can of soda before cowering on the ground.

Did I fail the simulation? I don’t even drink soda.

Perhaps, but the important thing, according to De Koninck and others, like author Alice Robb, is that I actively shared my dream. As inconsequential and boring as they can seem, dreams have proven to be helpful when shared or recorded. In a 1996 experiment, women who were going through divorces experienced positive self-esteem and insight changes after taking part in dream interpretation groups. De Koninck says “Dreams can be a source of self-knowledge that have adaptive value. Keeping a dream journal or sharing your dreams can help you to know yourself better or better adapt to situations.” But this doesn’t mean you should panic over a particularly weird or violent dream. He refers to dreaming as an “open season for the mind,” and says we should approach any interpretation open-mindedly instead of with some sort of a universal method.

What if you believe you don’t dream or — more likely — cannot remember your dreams? You are not necessarily maladaptive if you can’t remember your dreams, but there are ways to improve your dream recall. One is to simply think about dreams and dreaming more when you go to sleep and wake up (this could explain why I remembered so vividly my Alaskan romp with Judi Dench), and try to remember as much as possible when you first arise. Another is to vary the time you wake up. Since most of our dreaming happens in REM sleep, we are more likely to remember a dream if we wake during a REM cycle.

Whether our dreams are nightly firings of random artifacts of the brain or the products of important psychological evolution, they will never fail to terrify and bemuse us. In a brief time, we’ve come to embrace the “open season of the mind” and glean more from it than we could have thought possible. The future of dream research, a field that relies on new technology and mounding data, is promising.

Featured image: Ford Madox Brown: Parisina’s Sleep—Study for Head of Parisina (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a fascinating article on a crucial, basic topic, very well written and researched. I appreciate your insights and the links. The 1961 Post article is still timely, which I also read. As much that is known, which is considerable, there will always be more that will remain unknown behind the wall of sleep.

Deep sleep is key in saving your life and sanity. It’s God’s off and refresh button to restore your mind and body with the down time you need. Our society really has very little respect for sleep, but a lot for endless coffee, energy drinks like Monster, Throttle and the chemical tasting Diet Coke that are all SO unhealthily toxic. It’s okay for computers to sleep, but not people in the U.S.’s 24/7 mentality. No wonder so many people are so messed up!

I’m glad you could remember your dream with Ms. Dench so vividly. I can remember parts of mine IF I take a few 5mg capsules of melatonin, otherwise not so much. Sometimes it’s something I drove by the day before or observed, like a standard-size French Poodle being groomed (outrageously) in a pet shop I walked by. I didn’t think of the dog again, until he reappeared in my dream, partially shaved with cuffs and big hair.

The ’61 article supports the idea babies and animals dream. I’ve watched dogs eyes and occasional jerks in REM sleep. I can’t tell if it’s a dream or nightmare, but it is important, and the dog shouldn’t be disturbed. My dreams are in the present, but often in the past. The 18th century after seeing ‘1776’ and ‘The Favourite’ recently. The Civil War, ’20s parties for the rich (after going to various re-creative parties), the Depression and World War II.

Some are in color, others in black and white. My most vivid nightmare was recurring at 6 1/2, seeing the casket wrapped in the American flag (in color) following the Kennedy assassination and the four days of intense coverage on the black & white TV. I still think of it at least somewhat a few times every week, or the horrible Dallas film footage, but during waking hours, not sleeping, fortunately.

Some occasional recurring ones are where I’m falling in a Hitchcock ‘Vertigo’ style, or in a high-rise elevator where it’s falling and I’m afraid of the crash, but am jarred awake. I hate the spring forward coming up because it’s a sleep robber and throws everything off. I’m going to bed one hour earlier lately to hopefully minimize the disruption ahead of time.