Considering History: Robert E. Lee, James Longstreet, and the Truths of Civil War Memory

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

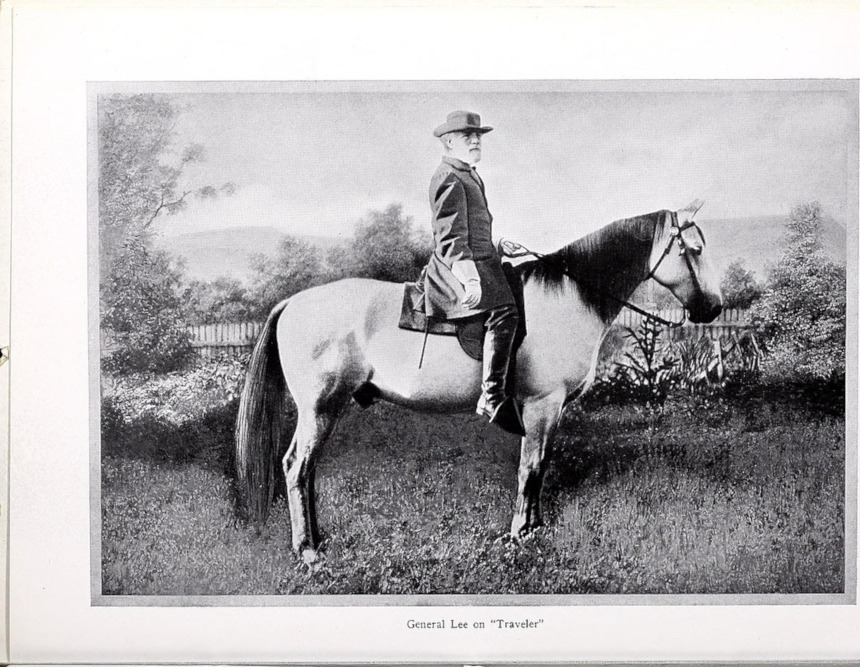

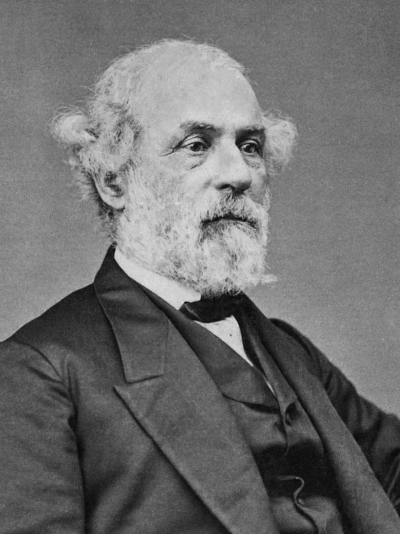

Growing up in Virginia, the Civil War was my gateway to a lifelong love of all things American history, and as a youthful Civil War buff, General Robert E. Lee was my idol. Even at a young age I certainly understood that the Confederacy had fought for a profoundly ignoble cause, and that the war’s outcome had been a just and necessary one. But I nonetheless embraced every element of the Lee mythos: the U.S. Army veteran who reluctantly joined the cause in solidarity with his home state but recognized the evils of slavery; the sensitive soul who declared (during a victory, the Battle of Fredericksburg) “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it”; and most of all (to a kid obsessed with military history and battle maps) the brilliant strategist who ran circles around the Union Army’s lesser military minds for much of the war.

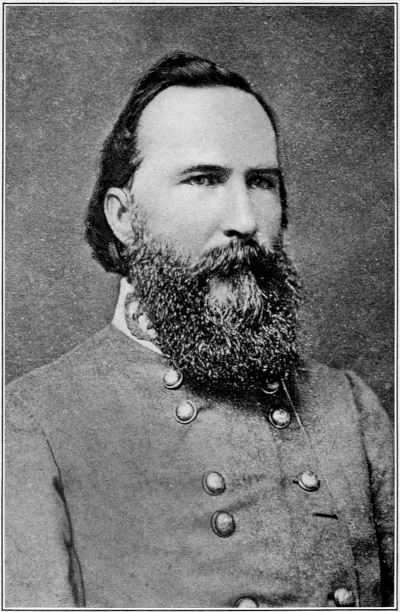

That last element in particular led me to a concurrent youthful disdain for General James Longstreet, one of Lee’s chief lieutenants throughout the war and yet a frequent dissenter from Lee’s strategies. That seemed particularly to be the case at the pivotal battle of Gettysburg, when (the story went) Longstreet’s disagreements with and deviations from Lee’s plans contributed to the Confederate loss. Yet whatever the details of that controversial military moment, the broader historical reality is both distinct and crucially telling: the deification of Lee and demonization of Longstreet reflect not military history at all, but instead the postwar and ongoing development of Civil War Memory.

Although Lee (1807-1870) was fourteen years older than Longstreet (1821-1904), the details of the two men’s careers through the Civil War are remarkably similar (and echo those of many other Civil War officers on both sides). Both graduated from West Point when they were 21 years old, both fought in the Mexican American War and received attention and acclaim for their service in that 1840s conflict, and both continued to serve the U.S. armed forces in multiple roles between that war’s conclusion and the Civil War’s outset. Both men were apparently uncertain about secession, not least because of those continued connections to the U.S. military; but both joined the Confederate Army in its first months of existence and would become two of its most prominent leaders throughout the war.

It was after the war’s end that the two men’s stories — and especially the collective perceptions and memories of them — would diverge much more fully. Lee died just a few years later, in 1870, but by then the national deification process traced in historian Thomas Lawrence Connolly’s The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society (1977) was already well underway. Those kinds of idealized tributes to Lee ramped up significantly after his death, leading Frederick Douglass to lament such “bombastic laudation” and “nauseating flatteries” to a man who “was a traitor and can be made nothing else.” But Lee was indeed made over the next few years into something quite different, the iconic hero celebrated in texts like Mississippi lawyer and author James D. Lynch’s epic poem Robert E. Lee, or, Heroes of the South (1876).

Other than Douglass, one of the few prominent late 19th century voices to resist this deification of Lee was none other than James Longstreet. In his 1896 memoir, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America , Longstreet sought to set the record straight about both specific events such as the Battle of Gettysburg and the overall national celebration of Lee as the war’s unquestioned genius. After quoting Lee’s reflections on the outset of Gettysburg’s third and final day of fighting, Longstreet writes simply, “This is disingenuous,” and the phrase sums up a good deal of his critique of both Lee’s memories and the collective memories of Lee. Although he does so in the respectful tone due to his commanding officer, Longstreet consistently creates a far different and much more critical picture of Lee and the war. For example, Lee opens his account of the night before that crucial third day by claiming that “the general plan was unchanged” and “Longstreet … was ordered to attack the next morning”; Longstreet counters that Lee “did not give or send me orders,” and so “in the absence of orders,” Longstreet had to utilize his own scouts and develop his own plan for the start of the next day’s (ultimately disastrous) attacks.

It would be easy to identify those critiques as the source of the neo-Confederate vitriol directed at Longstreet in the postbellum era. But the truth is that long before he published his memoirs, Longstreet had become a target for such hatred through his post-war actions, and specifically through his embrace of African American rights during and after Reconstruction. Longstreet joined the Republican Party, endorsing his friend (and Lee’s most formidable wartime adversary) Ulysses S. Grant for President in 1868 and taking on vital Reconstruction roles such as commander of all federal and state forces in New Orleans in 1872. In that latter role he commanded armed African American troops against a white supremacist militia at the city’s 1874 Battle of Liberty Place, when more than 8,000 men of the anti-Reconstruction White League sought to challenge and overturn a Louisiana gubernatorial election.

These Reconstruction conflicts comprised battles over America’s present and future but also over Civil War memory. Longstreet likewise resisted the era’s embrace of the Lost Cause narrative and its attempts to reframe the Civil War’s causes and meanings, at one point remarking to Grant, “I never heard of any other cause of the quarrel than slavery.” Yet the Lost Cause narrative came to dominate the postwar period so much so that by 1888, author Albion Tourgée wrote that American literature and culture had become “not only southern in type, but distinctly Confederate in sympathy.” And just as those national neo-Confederate sympathies made Lee into a marble man, they made Longstreet into at best a failure and at worst a villain.

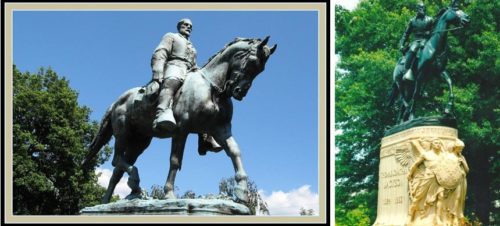

By the early 20th century, that process was complete, as reflected clearly in my hometown of Charlottesville, which in the late 1910s and early 1920s famously constructed its statues of Robert E. Lee and his now favored (and more clearly white supremacist) lieutenant, Stonewall Jackson. As I grew up in Charlottesville half a century later, it’s no wonder that this marble tribute to Lee helped cement his iconic status in my youthful Civil War Memory, and helped push Longstreet further to the fringes. Whatever happens to those two statues or any of the other Confederate memorials around the country, it’s long past time we collectively revisit and revise our memories of both these men and the racial and national images they symbolize.

Considering History: Confederate Memorials, Racist Histories, and Charlottesville

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On August 12th, 2017, as my sons and I drove from Boston to my childhood hometown of Charlottesville, Virginia for our annual visit with my parents, the small Central Virginia city erupted in violence. A gathering of white supremacists, neo-Confederates, and neo-Nazis known as the “Unite the Right” rally spurred counter-protests from antifa and other groups, and conflicts broke out again and again. In the day’s most horrific moment, a white supremacist named James Alex Fields Jr. drove his car into a group of counter-protesters, injuring thirty-five and murdering a young Charlottesville resident named Heather Heyer.

We’ll be driving down to Charlottesville again this coming weekend, on the one-year anniversary of those events. At the same time, many of the rally’s organizers and participants will be attending their own anniversary event, another “Unite the Right” rally in Washington, D.C. As that D.C. rally makes clear, these are national issues and conflicts that extend far beyond Charlottesville. Yet there are two distinct but interconnected histories within Charlottesville that provide vital contexts for these contemporary events: histories of Confederate memory and racial segregation.

Charlottesville saw no direct military action during the Civil War, but it was home to one of the war’s largest Confederate hospitals (which cared for more than 22,000 by the war’s end), and not coincidentally to one of its largest cemeteries for the Confederate dead (with more than 1000 buried there). For a few decades after the war, that cemetery remained largely private and unacknowledged. But in 1893 the Ladies’ Confederate Memorial Association (a predecessor to the Daughters of the Confederacy) dedicated a more formal Confederate Monument and Cemetery. The monument goes beyond the cemetery’s specific contexts to narrate a broader and striking reframing of Confederate memory, focused both on an idealization of the past and an extension of that heroic mythic history into the present, as it honors “the bravery, devotion, and performance of every Confederate soldier and the honor due every Confederate veteran.”

While the cemetery monument represented a significant step in the city’s memorialization of the Confederacy, it was more than two decades later that the city erected the now infamous downtown statues of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Dedicated in 1921 (Jackson) and 1924 (Lee), these statues were funded by, and constructed on land donated to the city by, Paul Goodlue McIntire, a local boy who had made a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange and returned to give much of it back to his hometown. McIntire also funded three other city parks and two different Charlottesville statues in honor of the Lewis and Clark expedition (Lewis was born in neighboring Albemarle county and the expedition set off from the area in 1804), so it’s fair to say that his interests in public land and collective memory extended well beyond the Confederacy. Yet the Lee and Jackson statues are located in Charlottesville’s most historic and central area, adjacent to its city hall and county courthouse (Jackson is directly outside the courthouse building), and thus occupy powerfully symbolic space in the city.

Moreover, there is at least one piece of direct evidence that McIntire’s public contributions were intended to preserve and further racial segregation in Charlottesville. As discovered by a Charlottesville Daily Progress reporter in 2009, the mid-1920s deed for the city’s McIntire Park, the only one of these McIntire-endowed parks named directly for the benefactor, includes this requirement: “Said property shall be held and used in perpetuity by the said City for a public park and playground for the white people of the City of Charlottesville.”

Of course all Southern cities practiced racial segregation in a variety of small and large ways throughout the Jim Crow era, but Charlottesville represents a particularly extreme case. That’s most especially true of the city’s public school system, which was one of the last in the United States to desegregate after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. All of the city’s public schools resisted desegregation for more than five years, supported by white supremacist officials such as U.S. Senator Harry Byrd and numerous members of the state General Assembly. The Assembly’s “massive resistance” bills gave Governor Lindsay Almond the authority to close any school where black and white students would attend together, and in the fall of 1958 he used that authority to close Charlottesville’s all-white Lane and Venable Elementary Schools for five months rather than admit African American students. All the city’s schools remained segregated throughout that school year, including Lane and Venable when they reopened in February 1959. That autumn, the first three African American students attended Lane High School, marking the start of integrated public education in the city. Although some Charlottesville public schools did not accept their first African American students for another year or two, the Supreme Court had ruled massive resistance unconstitutional in 1959, and the formal battle against educational integration in the city was over.

These were only the most nationally prominent of the city’s many late 1950s and 60s battles over integration. A mixed-race group of University of Virginia students and activists attempted to integrate the white-only University (movie) Theater in 1961, but the theater remained segregated until after the Civil Rights Act passed in July 1964. An even more overt conflict took place in 1963 at Buddy’s Restaurant, a popular establishment that, like many in the city, served only a white clientele. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement’s demonstrations across the South, and supported by the local NAACP chapter, a mixed-race group of protesters led by community activists and ministers Floyd and William Johnson attempted to stage a sit-in at Buddy’s on Memorial Day in 1963. They were denied entrance to the restaurant and met with violence by white customers and counter-protesters; both Floyd and William Johnson were physically assaulted (Floyd had to spend two nights in the hospital), and other protesters including University of Virginia History Professor and Civil Rights ally Paul Gaston were likewise bloodied. The resulting press coverage caused a number of local establishments to voluntarily desegregate, but Buddy’s remained segregated until the Civil Rights Act passed—and then its owner Buddy Glover chose to close rather than desegregate.

All of these histories came together in the current movement to remove the city’s Confederate monuments. While that campaign has been driven in part by city councilors such as Kristin Szakos and Vice Mayor Wes Bellamy, another prominent argument for removing the statues came from Charlottesville public school students of color. Zyahna Bryant, an African American student at Charlottesville High School (my own alma mater), organized a March 2016 change.org petition to the City Council requesting that the Lee statue in particular be removed. Bryant and hundreds of her high school peers (along with many other Charlottesville residents) signed off on the statement, which reads in part, “As a younger African American resident in this city, I am often exposed to different forms of racism that are embedded in the history of the south and particularly this city. My peers and I feel strongly about the removal of the statue because it makes us feel uncomfortable and it is very offensive. I do not go to the park for that reason, and I am certain that others feel the same way.”

How each American community remembers the various histories out of which it has developed, and just as importantly how it engages with what has been included and what has been left out of its public and collective memories, are thorny and vital 21st century questions. Charlottesville is poised to help us answer those questions, but only if we resist the kinds of divisive and violent voices, and their white supremacist visions of the past, that dominated the city in August 2017.

The War That Made Us Who We Are

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the March/April 2011 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

The war fought by Americans against Americans on American soil, for four excruciating years is still the deadliest war in American history. More than 600,000 fighting men were killed, some of them brothers in arms against brothers, and uncounted civilians died. It was a war over nothing less than whether to preserve or end the United States of America.

Most armed conflicts are about territory. This one was about ideas. The war would put an end to slavery. It would also create, if painfully, a cohesive single republic — more united than it had ever been before. In fact, the Civil War transformed the United States from a plural noun to a singular one. Before, you would say the United States “are.” Ever since the war, we say the United States “is.”

War became inevitable in December 1860, when South Carolina declared that it would no longer be a part of the United States. Abraham Lincoln had just been elected president, and the Southern states were convinced he would immediately outlaw slavery, on which their economy depended. They resolved to leave the Union rather than have their way of life overthrown. In February 1861, South Carolina and five other states announced that they were now the Confederate States of America. U.S. Army forces had to retreat to Fort Sumter, a granite fortification in the harbor of Charleston. When the forces refused to leave Fort Sumter, state militiamen waited, wore them down by preventing supplies from getting through, and then opened artillery fire on them. The bombardment lasted for 33 hours, until 4,000 shots and shells set Fort Sumter on fire. Finally, the U.S. flag came down, and the Fort surrendered.

No one imagined how long and devastating the war would be. The first big battle was fought in July 1861, at Bull Run in Virginia, near Washington, D.C., where Union troops attacked Confederate forces in hopes of putting a quick end to the conflict. The Confederates withstood the assault and then counterattacked, and the battle turned into a rout of the Union forces. Many hundreds on both sides were killed, and thousands more were injured. Americans began to see what a long nightmare they had trapped themselves in.

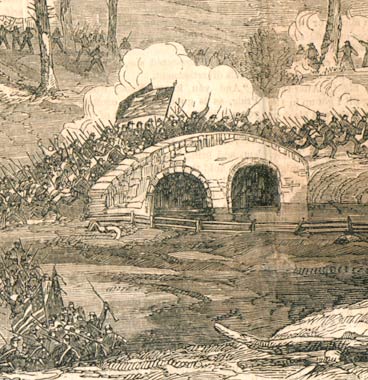

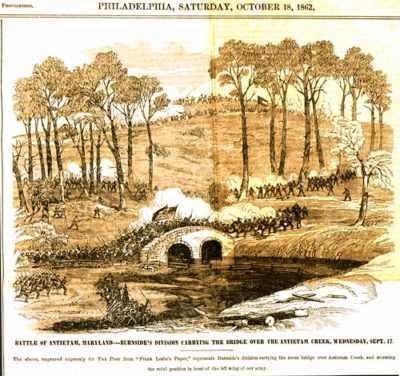

For more than a year after that, Southern troops won victory after victory under a brilliant general, Robert E. Lee, while Lincoln was disappointed by one irresolute Union general after another. One of the first big wins for the North was at The Battle of Antietam, in September 1862. The day it was fought remains the bloodiest day in American his- tory, with 23,000 casualties. Antietam turned a corner for the Union by stopping a northward advance by Lee’s army, and that victory gave Lincoln the confidence to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. On September 22, 1862, he made the sweeping, revolutionary announcement that all slaves in Confederate states would be free as of the following January 1.

Since the Proclamation applied only in states the federal government had no control over, it didn’t really free any- one except in a few Union-occupied parts of Confederate territory. But it told the world — and the captive blacks of the American South — that the war was not simply about preserving the Union. It was undeniably about slavery.

The war dragged on, with both sides more determined than ever after the Emancipation Proclamation. A turning point was reached in early July 1863, when Confeder- ate troops that had invaded the North were turned back in the epochal three-day battle in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, while in Mississippi, Union forces took control of the city of Vicksburg, freeing the Mississippi River from the Con- federacy. As President Lincoln put it, “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea.” That fall he delivered his great speech at the battlefield in Gettysburg, where 170,000 soldiers had clashed and 7,500 had been killed, saying “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Many thousands more were yet to die, though. Lincoln finally found the commanding general he had been looking for in Ulysses S. Grant, and Grant pursued a relentless war of attrition against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, while General William T. Sherman cut a crippling swath through Georgia, devastating the heart of the deep South. The war dragged on until April 1865, when Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Just a week later, President Lincoln was assassinated by an enraged Confederate sympathizer, John Wilkes Booth.

The wounds left by the war did not quickly or easily heal. Reconstruction, a bitterly opposed attempt by the North to remake the South, lasted until 1877 and ultimately failed.

The Civil War brought an end to slavery and reunited the nation, but the pain of reconciling the differences, many of which began with the birth of the republic, lingers still. The war made our motto true E pluribus unum — from many, one — but the work of making us one is never complete.

News of the Week: Jerry Lewis, ESPN’s Bad Decision, and 50 Years of the Big Mac

RIP Jerry Lewis, Dick Gregory, Jay Thomas, Brian Aldiss, Sonny Burgess, Sonny Landham, Jon Shepodd, Thomas Meehan, Bea Wain

It seems like we’re losing all of the classic stars of the ’50s and ’60s. There aren’t that many left now that Jerry Lewis has died. Lewis started doing standup in his late teens and just a few years later was teamed with singer Dean Martin. The duo spent 10 very successful years together, with their own TV show and a string of hit movies, before going their separate ways in 1956. Lewis spent decades as host of The Jerry Lewis Labor Day Telethon (he was dumped by the producers in 2009) and went on to do several successful solo movies, many of which he wrote, produced, directed, and starred in. Lewis died Sunday at the age of 91. His death has brought out many tributes from other comics who were influenced by Lewis.

Here’s the part of the 1976 telethon where Frank Sinatra reunited Martin and Lewis after 20 years. Lewis, along with James Kaplan, wrote a book in 2005 titled Dean and Me that is worth reading.

Dick Gregory was an influential comic who later became an influential political activist. He started doing standup at Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Club in Chicago in the early ’60s and in 1962 became the first black comic to sit on The Tonight Show with Jack Paar couch. Gregory died Saturday at the age of 84.

Jay Thomas was an actor and comic who appeared on such shows as Cheers, Mork & Mindy, and Murphy Brown, where he won two Emmys, and starred in two sitcoms of his own, Love & War and the underrated Married People. He was also host of his own daily talk show on SIRIUS Radio and appeared in several movies. Every year he appeared on David Letterman’s show at Christmas, where he would throw a football and try to hit the meatball on top of Dave’s Christmas tree (you had to see it to understand it) and tell a story about meeting Clayton Moore while working as a disc jockey. He died earlier this week at the age of 69.

Brian Aldiss was an acclaimed writer of many novels and short stories and is probably best known for his many works of science fiction. He died last week at the age of 92.

Sonny Burgess was a rockabilly star and Sun Records musician who founded the band the Pacers, who often opened up for Elvis Presley. Burgess was still performing up until last month and died last Thursday at the age of 88.

Sonny Landham was an actor who appeared in such films as Predator, 48 Hours, and Action Jackson and also ran for governor of Kentucky in 2003. He died last Thursday at the age of 76.

Jon Shepodd was the first person to play Paul Martin, Timmy’s dad on Lassie. When Cloris Leachman, who played his wife, Ruth, decided to leave the show after one season, producers felt they had to get rid of Shepodd too and start fresh, with June Lockhart and Hugh Reilly as Jon Provost’s parents. Shepodd died last Wednesday at the age of 89.

Thomas Meehan wrote the books for three big stage plays: The Producers, Hairspary, and Annie won him three Tony Awards. Other shows that Meehan wrote include Young Frankenstein, Rocky, Cry-Baby, and Elf. He started his career as a writer for The New Yorker. Meehan died earlier this week at the age of 88.

Bea Wain was one of the last living singers of the big band era. She sang such songs as “Deep Purple,” “My Reverie,” and “Heart and Soul,” and was actually the first person to record “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” though her recording was held back until after The Wizard of Oz came out. Wain died last weekend at the age of 100.

Bad Sportsmanship

In a time where every single week we say to ourselves “this is the craziest thing I’ve seen in a while,” I still have to say this is the craziest thing I’ve seen in a while.

Robert Lee is an Asian American college football announcer for ESPN, and the network announced this week that they’re taking him off the September 2 home opener at the University of Virginia. Can you guess why? Hint: It has to do with his name.

That’s right, ESPN has decided that Robert Lee’s name is a little too much like Robert E. Lee’s name, so they “collectively made the decision with Robert to switch games as the tragic events in Charlottesville were unfolding.” I wonder if college students even know who Robert E. Lee was?

I just hope The Saturday Evening Post doesn’t realize my first name is Robert and I live near a restaurant named Lee’s.

USS Indianapolis Wreckage Found

In the classic film Jaws, shark hunter Quint tells the story of how he was on the USS Indianapolis in 1945 when it was hit by two Japanese torpedoes. Of nearly 1,200 men on board, 300 went down the with the ship. The rest of the crew went into the water. Only 316 survived. The rest were killed by exposure, thirst, injuries, and … sharks.

The Indianapolis was lost in the sea for 72 years, but this week it was just found by an expedition funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

We've located wreckage of USS Indianapolis in Philippine Sea at 5500m below the sea. '35' on hull 1st confirmation: https://t.co/V29TLj1Ba4 pic.twitter.com/y5S7AU6OEl

— Paul Allen (@PaulGAllen) August 19, 2017

Let’s Talk about the Next Eclipse

I know, I know. We just got done with one eclipse this week and we’re already looking to the next one? It happens on April 8, 2024, and this time the path of totality will start in Mexico and go up towards New York and New England. Make sure you don’t use the same glasses you used this week, though. The lenses only last a few years, so you might as well just sell them on Craigslist as “collectors’ items.”

This is one of the best pics from the eclipse, a plane flying across just as the eclipse is happening in Lewiston, Idaho.

WOW! Kirsten Jorgensen in Lewiston, ID was about to pack up & go inside then saw the plane. She ran to the camera & click!#Eclipse2017 pic.twitter.com/6RxcXURrl3

— Mike Seidel (@mikeseidel) August 22, 2017

Millennials Hate Black-and-White Movies, Love Paper Towels

It’s always something with you millennials. First you try to destroy the cereal industry because it takes too long to clean the bowl and spoon, and then you reveal that you can’t even watch a black-and-white movie all the way through? What’s next, are you going to stop using napkins?

Yes. Business Insider has a list of the industries and products that generation Y has either killed or at the very least has hurt deeply, including casual dining places like Applebee’s and Hooters, homeownership, beer, motorcycles, golf, and napkins. Apparently, millennials are in love with paper towels (though I like to think they’re just barbarians who wipe their mouths with their sleeves) because they’re more practical than napkins and you can clean up more. But wait, aren’t millennials the ones who hate to take the time to clean even a cereal bowl?

I have to agree with one item that they don’t use anymore: bars of soap. Though I washed with Ivory every day when I was a kid, I haven’t used a bar of soap in 15 years.

Don’t be funny. I mean I use liquid soap now.

Two All-Beef Patties, Special Sauce, Lettuce, Cheese, Pickles, Onions on a Sesame Seed Bun

McDonald’s popular burger was invented by Jim Delligatti at the Uniontown, Pennsylvania, location and first served on August 22, 1967. Here’s a commercial from that same year:

Interesting that this commercial uses the line “… and a sesame seed bun” when other commercials use “on.” Okay, it’s not that interesting.

This Week in History

Dorothy Parker Born (August 22, 1893)

The witty, often caustic writer wrote for The Saturday Evening Post several times. Here are three of the poems we published in 1923, and here are 25 of her best quotes.

British Invade Washington, D.C. (August 24, 1814)

The White House was one of the buildings burned when British troops marched into Washington during the War of 1812. It was uninhabitable for three years.

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History

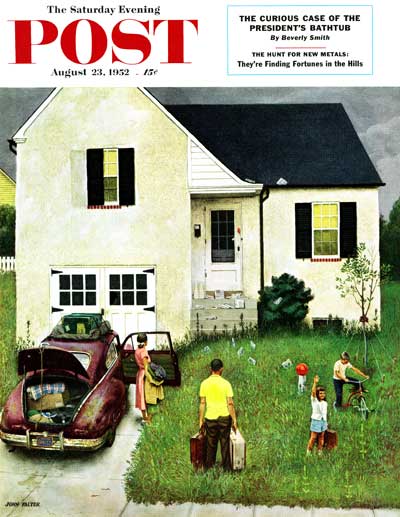

“Home from Vacation” (August 23, 1952)

John Falter

August 23 1952

Here it is, August 25, which means that summer will soon be over. Oh, sure, summer technically doesn’t end until September 22, but we all know it ends when the kids go back to school. In some areas that has already happened and in other places school starts the day after Labor Day. In this cover by John Falter, the family is coming home after their vacation and unloading the car, about to find out what bills have been piling up while they were gone.

National Cherry Popsicle Day

“Popsicle” is actually a registered trademark of Unilever, though we seem to call every frozen ice pop a “popsicle.” The same way we call every adhesive bandage a “band-aid,” even though there’s only one Band-Aid.

Anyway, I have no idea why cherry Popsicles get their own special day tomorrow, August 26. I’m an orange, grape, or root-beer guy.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

National Dog Day (August 26)

Is it a controversial thing to say that dogs are better than cats? But they are! Here’s the official National Dog Day site, where you can learn how to celebrate the day with your best friend. Cats have to wait until October 29 for their day.

Frankenstein Day (August 30)

Why is Frankenstein celebrated on August 30? That’s the birthday of author Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which was published in 1818. On a related note, here’s a 1962 Post interview with Boris Karloff, who played Frankenstein in the 1931 film adaption.

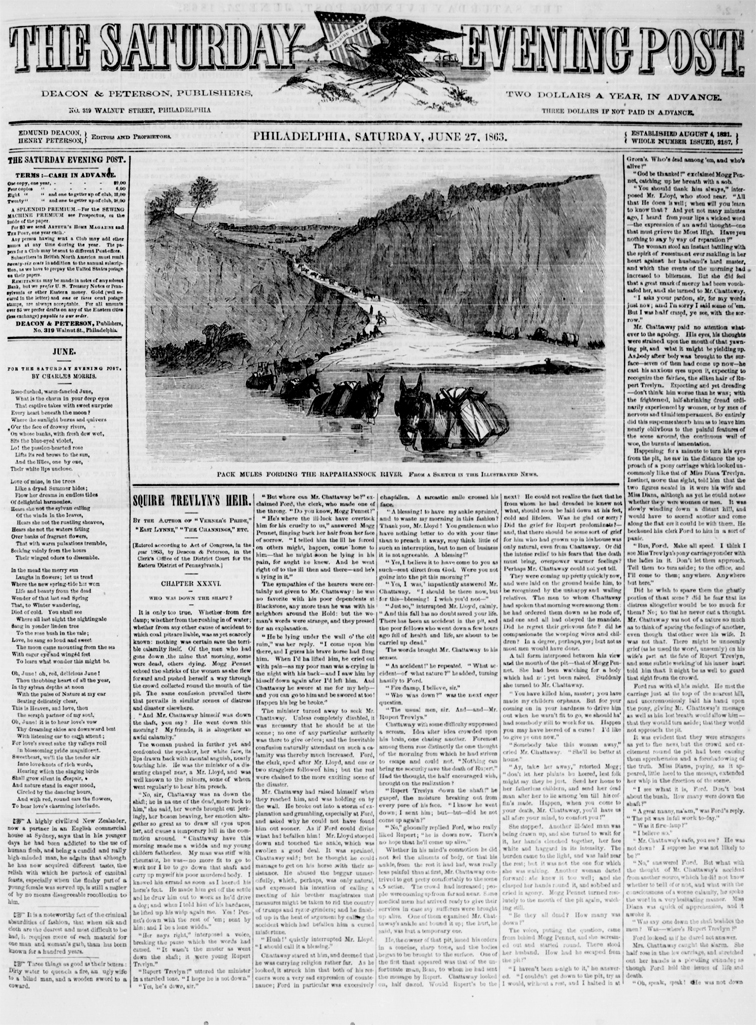

Gettysburg 150 Years Later

Commemorate the 150th anniversary of the pivotal Civil War battle by reflecting on original reports and illustrations from The Saturday Evening Post.

Little-Known Facts About the Civil War

Did you know Lincoln wanted Robert E. Lee to command the Union Army? Or that more than 10,000 Native Americans fought in the war?

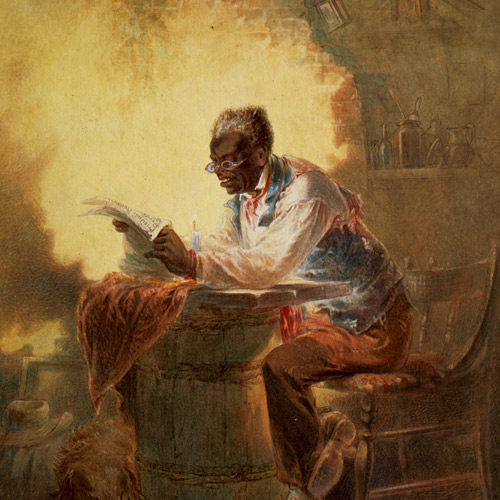

‘Coming Generations Will Call You Blessed’

An army surgeon writes of his gratitude to the civilian volunteers of the Sanitary Commission, seeing them as a sign that mankind has entered a new era.

Little Women Among the Casualties

In 1863, the Post published Louisa May Alcott’s harrowing description of her work as a Civil War nurse.

Where the Civil War was Won

How the Post covered the Battle of Gettysburg.

Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops

Thousands of soldiers’ lives were saved by a special organization of volunteers.

Scrambling for Troops

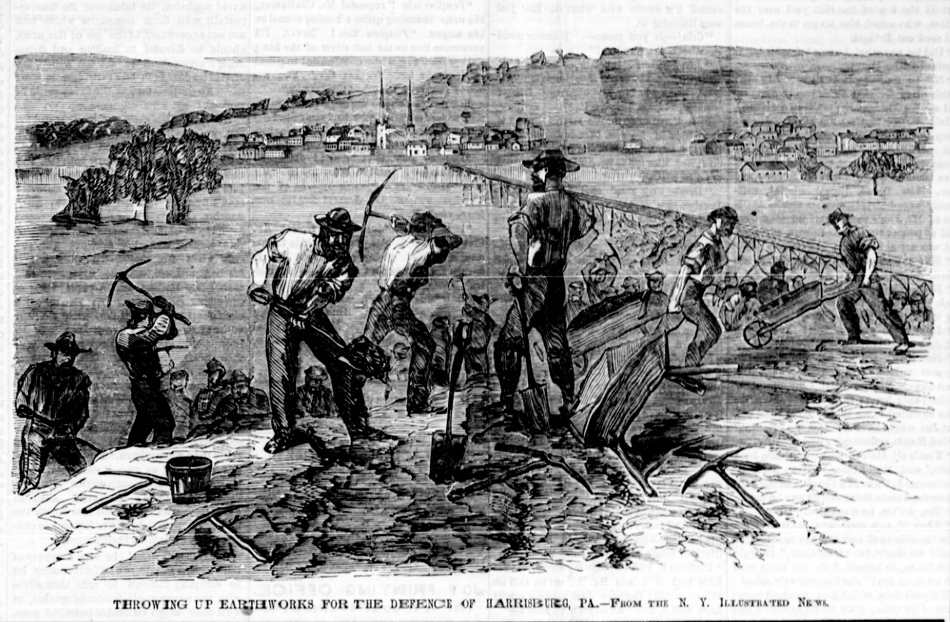

The news of the Confederates’ invasion inspired Philadelphia, panicked Harrisburg, and brought renewed attention to the draft.

The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move

We begin a series of the Post‘s reporting on the Gettysburg Campaign with the initial news of the invasion and hopes that a state militia could defeat Gen. Robert E. Lee.

The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move

We begin a series of the Post’s reporting on the Gettysburg Campaign with the initial news of the invasion.

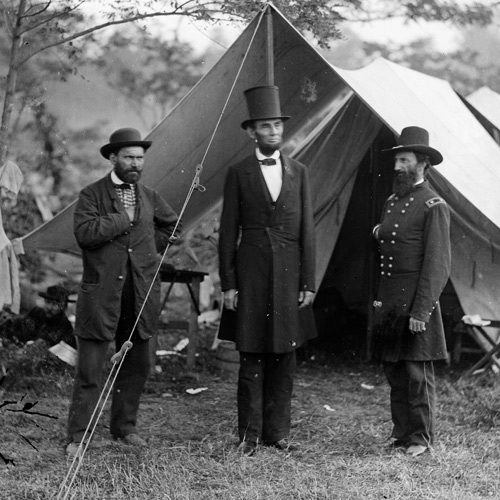

As was its style, the Post presented the news on Page 2 of the June 27, 1863, issue. Beneath a simple headline, “The War,” it calmly announced the opening of what would become a pivotal moment in United States history:

“Since our last issue, we have had a considerable amount of excitement in this city, owing to the reports of a rebel inroad into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Exaggerated as those reports so far have been, it is better to be prepared for the worst, than to run any risk in such a serious manner.”

The early reports were not encouraging, the article added. The federal government had believed the Confederate army, under General Robert E. Lee, was camped near Chancellorsville, Virginia, directly across the Rappahannock River from the Union army. But starting in June, Lee had quietly begun withdrawing his 70,000-man army and marching them north, toward Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Ahead of him lay only small, scattered groups of Union forces. The first to encounter the advancing rebels were the 7,000 Yankees at Winchester, Virginia. They were quickly brushed aside and then, wrote the editors, Pennsylvania “lay open for the moment to any rebel body which had the temerity to enter.”

On June 19, the Confederates had crossed into Maryland. Two days later, they entered Pennsylvania. When they reached Chambersburg on June 28, they were still 160 miles from Philadelphia, and the Post’s offices. But those miles were nearly empty of any defending troops; the Union army had begun chasing after Lee’s army on June 11, but they were still south, unable to protect Philadelphia or Washington, D.C.

Yet the Post editors remained confident that the men of Pennsylvania could, and would, throw the invaders back across the Mason-Dixon Line. They assured their readers that a state militia could be quickly formed, and it would be far more effective than expected. “We hear, in these times, a great deal of underrating of the militia, as unreliable against veteran troops. Men are disposed to think it useless to trust our safety to such a force. But it seems to be forgotten that these militia are now upon the soil of their own states, fighting in defense of all that we hold dear.”

The Post explained that militia soldiers of the South had proven they could be highly effective in pushing back the Union armies that entered their states. (Though, when they had to fight beyond their state lines, their effectiveness disappeared. “They failed thus at Antietam, and South Mountain, and Perryville, and Mill Spring, and other places.”)

The North shouldn’t dismiss the fighting skills of raw recruits, the article maintained. They had heard witnesses from several battles say raw troops had performed just as well as veteran soldiers, sometimes even better. After all, it was a hastily formed militia that won the famous Revolutionary war battle of Bunker Hill, not to mention the War of 1812’s Battle of New Orleans.

Regardless of how well this green militia could fight, it was all the state had to defend itself until the Union’s Army of the Potomac could arrive. Pennsylvania’s governor called for 90,000 men to form a state militia, and hundreds of men traveled to Harrisburg to muster in. But when they arrived, many changed their minds upon learning the enlistment period of six months was longer than they thought necessary to meet the crisis.

Instead of criticizing their lack of spirit, the Post agreed with the volunteers’ decision not to enlist: “We do not censure in the least, those of our citizens who recently returned from Harrisburg, because their business engagements did not admit even a conditional pledge to serve for six months.” If the emergency were truly short-lived, they argued, there wouldn’t be any need for such a long enlistment.

Seeing the poor response, the governor reduced his request to 60,000 men and an enlistment of just three months.

While the debate about terms of service continued, the Confederates were helping themselves to the riches of Pennsylvania. Rebel troops who had long been living on short rations in a countryside ruined by war suddenly found themselves among the fat livestock and bulging granaries on Pennsylvania Dutch farms. Lee had ordered his men not to take from the local farmers, but to pay for what they requisitioned in (valueless) Confederate money. But many Confederates didn’t bother with such niceties as payment as they helped themselves to livestock, crops, furniture, clothing, and anything that could be loaded onto a wagon. Even worse, several hundred black Americans—some escaped slaves as well as fourth-generation free Pennsylvanians—were being seized and sent south to be sold as slaves.

No one in the North could be sure where Lee was headed, or what he had in mind. A report filed in the Post on June 28 indicated Harrisburg was the likely target. “The capital of the state is in danger. The enemy is within four miles of our works and advancing. The cannonading has been distinctly heard for three hours.”

Northerners knew that if Lee could take Harrisburg and its resources, he might easily turn southeast and seize Washington, D.C., just 120 miles away.

The Post’s editors never lost faith in Pennsylvania, or the Union. They believed Lee had made a bold move, but a hazardous one. “Properly improved on the part of the North and the Government, it may have the most favorable results. Let the friends of the Union seize now the propitious moment.”

What the Post didn’t know was that the Union army was closer than they, or Lee, expected.

Coming Next: Scrambling for Troops

Antietam: Our Post-Battle Report

September 17, 2012, marks the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single-day battle in American history.

Late in the second year of the Civil War, the Confederate army switched from defense to offense. General Robert E. Lee marched the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland, which had remained loyal to the Union.

He had recently defeated the Union forces at the Second Battle of Bull Run and decided it would be better to keep the momentum from this victory by a march into Union territory. Maryland was the natural choice; a large number of slaveholders in the state were strong supporters of the Confederacy. Lee hoped they would join his army and bring needed supplies. If he could score a victory against the Union forces, the Confederacy might win recognition from Great Britain and France. If so, the South could resume trade with Europe. The British Navy would break the Union’s blockade so that cotton could be shipped to the mills that were now laying idle from lack of material. Lincoln would have to fight the Confederacy and the British Empire. If Lee could win a victory.

The odds were in his favor. He was opposed by the Union’s General McClellan—an able administrator but a hesitant commander who always over-estimated the enemy. He had resisted Lincoln’s orders to move south toward Richmond. When Lincoln finally ordered him south, he was bluffed out of a strong position outside Richmond, Virginia, so close he could hear the church bells of the city.

Now Lee was coming at him. For the first time, the great Confederate commander would fight an offensive campaign, which was always more risky. It didn’t help that a union soldier found a copy of his strategy, copied for his generals. McClellan would never again have such an advantage. The Southern command soon realized that the orders had been found by the Union, but Lee stayed with his plan. McClellan attached Lee and, at Antietam, had the advantage for once.

Had he been a more decisive general—as determined as General Grant, for example—he might have defeated and captured Lee’s army. But McClellan wasn’t that bold or imaginative a general. And Lee was. The Confederates were able to withdraw their forces in the face of a large Union army.

All the same, it was a rare defeat for the Confederates. And for both sides, it was particularly bloody. In one day, nearly 23,000 Americans were killed, wounded, or missing.

Lincoln was shocked that General McClellan would not pursue the Confederate army and make it a decisive, war-determining battle. Yet, it was still a victory, and there had been very few for the North. Lincoln used the opportunity to announce a momentous change in policy, and a change in the direction of the war.

The following is taken from “The Recent Contests” from The Saturday Evening Post, September 27, 1862.

A week of anxiety ends with the joyful assurance that the rebel invaders have been forced to fly from “Maryland, My Maryland,” and entirely give up for the present the prospect of overrunning Pennsylvania.

It is evident that it was a most desperate struggle, in which though we can scarcely claim a decisive victory, the balance of advantages was decidedly in favor of the Union forces. The next day both armies were apparently too much exhausted to recommence the contest, the rebels probably secretly employing themselves in commencing their retreat into Virginia. On Friday, judging from our present advices, they completed their passage of the Potomac—with how much loss of men, trains, and artillery, we are yet unable to say. The amount of such loss of course will determine the extent of the disorganization they have sustained, and the character of the defeat they have suffered.

It is probable that the designs of the rebels in their recent movement were as follows:

1. To capture Harper’s Ferry and the 12,000 men at that place, by surrounding it, and moving on it from the North, from which side it is said to be least defensible, the Maryland heights being higher than the Virginia ones.

2. To replenish their supplies.

3. To raise Maryland in their favor, and largely recruit their forces.

4. To menace Baltimore and Washington, and the railroad communications of those cities with the North.

5. To invade Pennsylvania by way of the Cumberland Valley, allow us in this state to feel the ravages of war, supply themselves at will from our overflowing resources, and sicken us of the contest.

Of all these object the rebels have gained the first, and, it may be, in a degree, the second. Owing to shameful incompetency or treachery, Harper’s Ferry was captured. Whether the report of the recapture is true, we are at present unable to say.

But Maryland would not rise—even her secessionists will not put their property and lives in peril on so desperate a venture. For they see that even if the North were defeated, and the Union allowed to be dissevered, the North and Pennsylvania must at least insist on the Potomac for a border line.

To cross the Potomac is in fact to invade Pennsylvania—recent events have impressed this upon the great majority of our population. It therefore does not seem possible for Maryland to be severed from Pennsylvania without exposing both of them to great peril.