News of the Week: Changing Time, Selling Rockwell, and Brushing Your Teeth with Oprah

Goodbye “Spring Ahead, Fall Back?”

I like the fact that it gets dark really early now. I find the months that it stays light and warm until 8:30 p.m. depressing. Does that make me weird? Maybe I’m weird.

Apparently there are residents of my state of Massachusetts who hold the opposite view. They want to get rid of Daylight Saving Time for good. A state commission wants to have Massachusetts join the Atlantic time zone, which means the state would be an hour ahead of the Eastern time zone. Farmers say this would help them, but at the same time, it would mess up things like shopping and TV-show watching. Also, it would be weird if not impossible for Massachusetts to do it alone, with the other New England states and New York staying on Eastern time.

One of the other reasons the commission wants to change the time is to attract millennials to Massachusetts, and supposedly millennials hate the dark and cold weather.

Yes, that reason is exactly as stupid as it sounds.

Rockwell Paintings Can Be Sold After All

A judge has ruled that a museum can sell iconic Norman Rockwell paintings, against the wishes of Rockwell’s family.

Rockwell had donated the two works, including his famous Shuffleton’s Barbershop painting, to the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The museum says that they are having financial troubles and want to sell the two paintings to raise money. They’re looking to get around $50 million.

The Rockwell family, including Rockwell’s grandson Tom, say that Rockwell donated the two paintings to the museum so the public could continue to see them forever. The family sued to stop the sale, but in a 25-page decision, Judge John Agostini ruled in favor of the museum.

YOU Get an Electric Toothbrush, and YOU Get an Electric Toothbrush!

It’s November, and that means Oprah Winfrey has once again chosen her Favorite Things, those must-have items for Christmas. For the past few years she has teamed up with Amazon, which helpfully provides links to each of the items Oprah puts on her list. This year, Oprah appears at Amazon in a flowing blue–and-white dress, delivering beautifully wrapped gifts with the help of her sled dogs.

The items range in price from under $50 (notepads, hand cream, and jammies) to a lot more than that (a Samsung TV in a picture frame). In between, you’ll find books, dog biscuits, a pizza oven, an electric toothbrush, puzzles, even a Greenberg smoked turkey.

You’ll also find something called “Smooshpants.” I don’t know what Smooshpants are.

If It’s Sunday, It’s Meet the Press

Meet the Press is the longest-running TV show in history, having debuted on November 6, 1947 (CBS Evening News is second, having started six months later). NBC has set up a special web page that includes a history of the show as well as several clips from its most important interviews. The show’s first moderator was a pioneering woman named Martha Rountree, and one of the early panelists was Edgar Allen Poe.

No, not that Edgar Allan Poe, this Edgar Allen Poe. The show’s not that old.

The Return of Harold the Baseball Player

Something else celebrating 70 years is the classic Christmas film Miracle on 34th Street, which just so happens to be my second-favorite film of all time, after It’s a Wonderful Life. Miracle is set at Macy’s department store and a major part of the plot revolves around the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. One of the parade balloons seen in the film, Harold the Baseball Player, is making a comeback in this year’s parade. To honor his appearance in the film, Harold is being repainted black and white so he looks like he did in the black–and-white film.

You can watch the parade on NBC Thanksgiving morning (November 23) at 9 a.m. To really celebrate the 70th anniversary of Miracle on 34th Street and Harold, you should turn off the color on your television.

RIP John Hillerman

John Hillerman is probably best known for his role as Jonathan Higgins, the ex–British military man who took care of the Robin Masters estate on Magnum, P.I. Hillerman also had regular roles on Valerie, One Day at a Time, and The Betty White Show and appeared in movies like Blazing Saddles, The Last Picture Show, Chinatown, and Paper Moon. He died yesterday at the age of 84.

And no, for the last time, there’s no way Higgins could really be Robin Masters.

This Week in History

Will Rogers Born (November 4, 1879)

The death of the American humorist, in a 1935 plane crash in Alaska, paved the way for another writer to take over his weekly syndicated column, even if she didn’t particularly like to write.

“You Won’t Have Nixon to Kick Around” Speech (November 7, 1962)

This was supposedly Richard Nixon’s last press conference. He was angry at the media after losing the 1962 California gubernatorial race to Pat Brown. But if you recall, we did indeed hear from Nixon again.

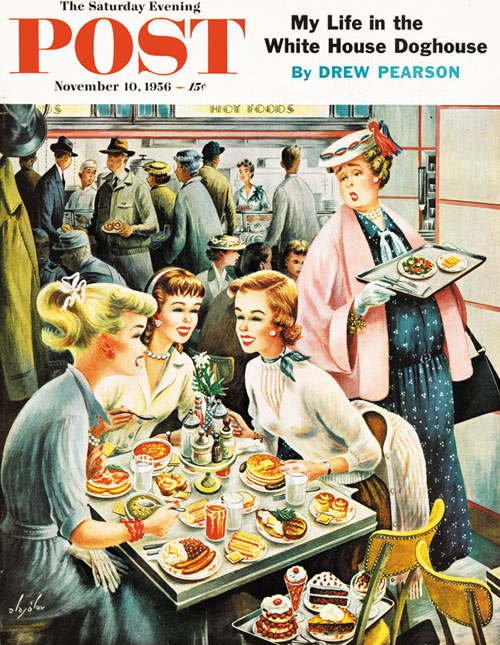

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Cafeteria Dieter (November 10, 1956)

Constantin Alajalov

November 10, 1956

Sometimes I like to look at a Post cover without knowing the title, to see if I can figure out what the cover is supposed to be about. I knew the title of this Constantin Alájalov cover, but if I hadn’t, I could have guessed “Nosy Lady” or “Gossip Girls” or maybe “Older Lady Wishes She Could Eat Like All of These Younger Girls, Oh My God There’s Even Dessert on the Chair.” That last one isn’t far off from the actual title.

Veterans Day

The day is officially tomorrow, November 11, but because that’s a Saturday, it is observed nationally today (if Veterans Day falls on a Sunday, it is observed on Monday). Here’s a quick history of the day, and here’s a piece by Post Archive Director Jeff Nilsson on America’s early efforts to honor our veterans.

Monday Is National Indian Pudding Day

This is a New England favorite I don’t think I’ve had in three decades. It’s comfort food in a bowl, with its warm molasses, brown sugar, and cinnamon. Here’s a classic recipe from Yankee magazine, another New England favorite. Takes about two hours or so.

It’s often served with vanilla ice cream or whipped cream, but you can probably skip that if you’re a dieter, cafeteria or otherwise.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

National Clean Out Your Refrigerator Day (November 15)

I truly hope that you don’t clean out your refrigerator only once a year, but if that’s the case, the week before Thanksgiving is probably a good time to do it.

National Fast Food Day (November 16)

I know several people who celebrate National Fast Food Day every day. They call it “breakfast” or “lunch.”

A Year in Review: The Top 10 Stories of 2012

It’s been a great year for the Post, editorially speaking. We’ve covered a broad range of issues, from hot-button political topics like the wealth gap and social security to unique finds in our archives on mysterious crimes, the Titanic, and Rockwell paintings.

Amidst the trove of content we’ve provided our readers in the last 12 months, 10 stories had more traffic on our website and social media than all the rest. Here are the Post‘s top stories of 2012.

Statin drugs benefit some people immensely but are taken by millions more. If you’re at low risk for heart disease, taking drugs to lower your cholesterol may be doing you no good. Is it time we took a second look at statins?

Sharon Begley examines the pros and cons of the statin pill push, and finds that many doctors are staunchly against their widespread use.

Read more »

Despite a half-century of inquiry, the circumstances surrounding the death of an 8-year-old boy are still a mystery. What makes this case even more bizarre is that this boy, by all accounts, never existed. To this day his name, birthplace, and even his lineage are unknown.

Read more »

Thinking of taking the plunge? That’s exactly why director Steven Spielberg keeps this Rockwell painting in his office.

Historian and archivist Diana Denny divulges interesting facts about the models, the climate of the era, and Rockwell himself.

Read more »

This 1950 article claims that, in the event of an atomic bomb, “there are protective measures you can take—and proof that the blast is not always so fatal and frightful as you think.”

Read more »

As consumers increasingly demand organic produce, and as massive industrial farms rise to meet their needs, will it spell the end of the family-run, lovingly tended, earth-friendly farm?

Barry Yeoman analyzes the challenges and pitfalls grocers and small organic farms alike face in the wake of the growing demand for healthier foods.

Read more »

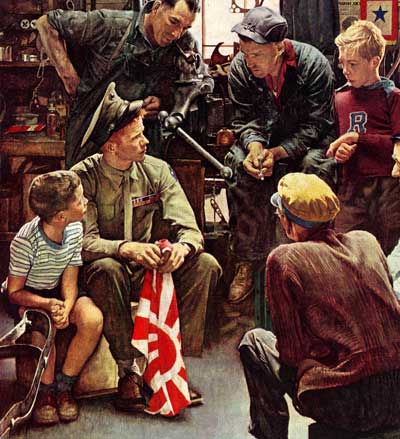

In honor of Memorial Day, we gathered some of Norman Rockwell’s most iconic art from both world wars.

Read more »

One hundred years after the Titanic sank, we explore the Post‘s 1912 editorial on the great tragedy. Were the British and American governments to blame for the 1,500 deaths? Our coverage explored the oversights, shortcomings, and outrage in the wake of the ocean liner’s horrific end.

Read more »

You’ve heard the rumors. Here are the facts. The Post examines the timeline of social security from its advent, parsing why it was started, what it aimed to do, how it helped Americans, and why there’s such a fuss about it in the current political climate.

Read more »

The country is polarized and embattled to the point of dysfunction. What will it take to bring us back together?

A self-described “one-time liberal atheist,” Jonathan Haidt discusses the differences between conservative and liberal worldviews, how he came to understand the other side, and asks whether or not this country can find a tolerant middle ground.

Read more »

Betsa Marsh took Post readers to the somewhat forgotten land of stately, grand hotels, where unlike today’s varieties, the opulence comes from the resort’s history and refined elegance, not its glitz and glamour. To stay at any of these lodgings is to venture back to another, more genteel time.

Read more »

Classic Covers: Rockwell Behind The Canvas

You know these classic Rockwell paintings, but do you know the details behind them?

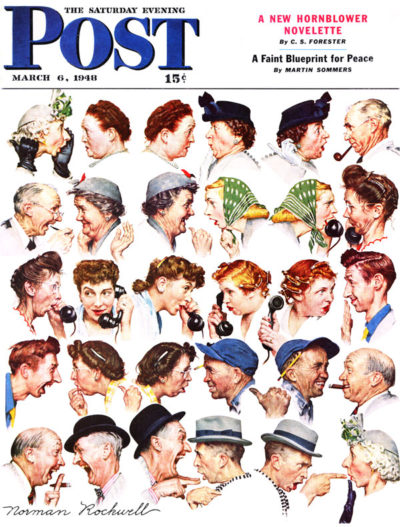

The Gossips—March 6, 1948

It seems Rockwell had a neighbor who started a disagreeable rumor about him. What can one do about a nasty gossip? Well, if you are a famous illustrator, you can paint a cover about it.

It started with just a couple of people, then it just grew, leaving Rockwell in need of more models. The result, said the editors, is that we see “almost the entire adult population of Arlington, Vermont.” As he worked on the project, the artist worried that his friends and neighbors might be offended, so he included his wife and himself. Mary Rockwell is second and third in the third row, spreading the rumor via rotary phone. In the gray felt hat in the bottom row is, of course, the artist himself (you can click on the image for a close-up). You’ll notice the lady at the end is the one at the beginning who started the rumor, and our friend Rockwell appears to be giving her a piece of his mind. Apparently, the neighbor who started the rumor in real life never spoke to Rockwell again. I have a feeling it was no great loss. The lesson here is: don’t anger someone whose Saturday Evening Post covers are viewed by millions.

No Swimming—June 4, 1921

These boys sure are hightailing it out of there! Even the dog is hauling tail (okay, sorry). Rockwell expert Robert Berridge wrote about this cover in a recent edition of The Saturday Evening Post magazine. “Franklin Lischke—the freckle-faced lad in the middle,” writes Berridge, was so taken with Rockwell’s work, he ended up studying art himself, becoming a successful commercial artist.

The question remained for decades: what were the boys running from? “Could it have been the pond owner,” Berridge asked, “an irritated bull, or a group of passing girls?” The model himself told Berridge. Answer at the end of this piece…

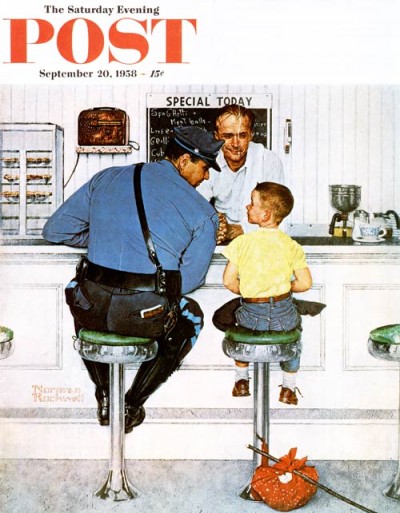

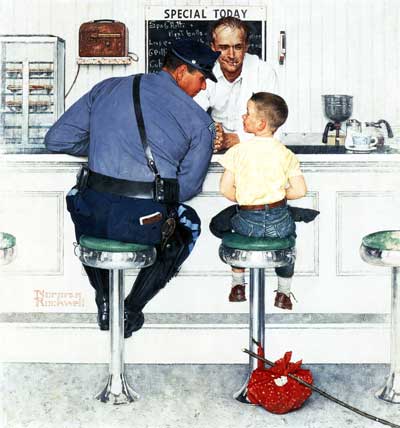

The Runaway—September 20, 1958

“The Runaway” is one of everyone’s favorite Rockwell covers. A neighbor of Rockwell’s, Richard Clemens, just happened to be a Massachusetts State Trooper and gladly posed for the artist, along with young Eddie Lock. After posing for this now iconic cover in 1958, Richard and Eddie didn’t see each other again until 1971 when they happened to find themselves sitting next to each other in an evening class (in logic) at a community college.

Besides the touching contrast between the large man and the little boy, there is a myriad of details Rockwell meticulously included: The old-time radio, the pies in the case, the coffee starting to perk and just turning brown, for example. The artist’s “mania for detail” extends to the stools: they were “spring-loaded,” causing the police officer’s seat to sink lower than boy’s. Even the chrome on the stools reflects the front of the diner.

By the way, the answer to the question of the running boys: why were they desperately trying to flee? They weren’t fearing the land owner or trying to hide their bare bottoms from an unexpected visit by girls; they were fleeing a swarm of bees! Thank you, Robert Berridge, for answering that long-standing question!

Norman Rockwell: America’s Artist

Norman Rockwell didn’t create his celebrated images using only brush and paint. They often took shape first as scenes that Rockwell literally acted out, not only for his editors at the Post, but his real-life models, too. “It was strenuous,” he once explained, “but I felt it was the best way to get across my meaning.” And so he would enthusiastically play out his visions and ideas, a one-man show packed with just the right expressions, giving enough details of each persona in the scene to inspire his models and, more importantly, get his editors to buy his ideas.

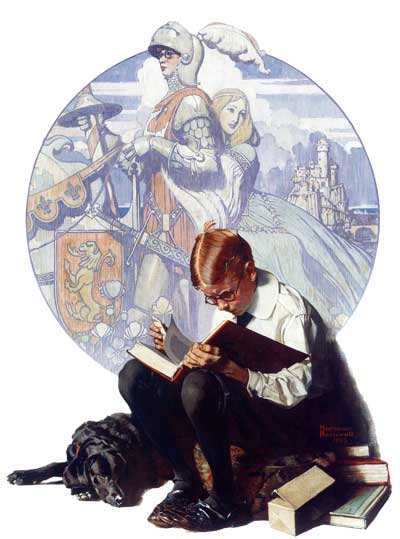

Now, more than 30 years after his death, Rockwell is still acknowledged for deftly chronicling the best of 20th century American life with vignettes of simple emotions evoked by everyday people. This phenomenon is a resounding testament to Rockwell’s prowess as a storyteller and is the subject of another kind of one-man show: the upcoming exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., titled Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. The exhibit, assembled from the private collections of these two popular film directors, will feature rarely viewed pieces of Rockwell’s work, including George Lucas’ favorite, Lands of Enchantment, which shows a youngster imagining himself as an armor-clad knight riding away with a beautiful girl. The point is not the boy reading, but how the book inspires the boy’s imagination, taking him, in idealized form, to another time and place.

“It’s a painting celebrating literature, the magic that happens when you read a story and the story comes alive for you,” notes Lucas.

by Norman Rockwell

November 10, 1923

© SEPS.

And that’s just one of the 50-plus images from the highly anticipated exhibit, which runs from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The exhibit will also explore the artist’s elaborate creative process while spotlighting Rockwell’s ability to capture the range of human expression and distill whole episodes of American life into single and broadly accessible moments by drawing upon a full arsenal of skills that would have served him well as a filmmaker.

According to Virginia Mecklenburg, the museum’s senior curator, both Lucas and Spielberg were inspired by Rockwell’s creativity and tender subject matter, as well as his warm depictions of America without cynicism.

“Both filmmakers grew up in the 1950s, enjoying Rockwell’s illustrations on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post,” says Mecklenburg. “They share the artist’s sensibilities in many ways, and have sought to express similar values, such as loyalty, courage, and friendship, in their own work.”

When working on Star Wars, Lucas said that he realized there needed to be a kind of film that expresses those values, as well as the mythological realities of life—the deeper psychological movements of the way we conduct our lives—that are evident in fairy tales. “Once I got into Star Wars, it struck me that we had lost all that—a whole generation was growing up without fairy tales. You just don’t get them anymore, and that’s the best stuff in the world,” Lucas explains.

Like Lucas, Rockwell was an original. He grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, living in a rough-and-tumble New York boarding house. He quit high school to attend classes at the Art Students League in New York, and was already a working, if occasionally struggling, artist in his teens. But in 1916, when he sold his first cover to the Post, he began to carve what would become a unique niche in the American psyche. Throughout the course of 323 Post covers over the next 50 years, he would stoke and affirm our pride in who and what we are at our very best moments, even if most of us rarely experienced the fresh-faced version of the world.

“Storytelling was very important to Norman Rockwell,” says Lucas. “Every image has either the middle or the end of a story, and you can already see the beginning even though it’s not there. You can see all the missing parts of the story because he took that one frame that sort of tells you everything you need to know.

by Norman Rockwell

September 2, 1939

© 1939 SEPS.

“And, of course, in filmmaking we strive for that. We strive to get images that convey, visually, a lot of information without having to spend a lot of time at it. Norman Rockwell was a master at that—he was a master at telling a story in one frame,” explains Lucas.

That concentration of information as well as emotion is something inherent in Rockwell’s art. Emotion certainly spoke to Steven Spielberg when he first saw one of his favorite Rockwell paintings, High Dive, the August 16, 1947 Post cover that depicts a boy at the top of what must be (or so we imagine from the boy’s expression) a towering diving board. He crouches high above a swimming pool, too afraid to either jump or climb back down. The painting hangs in Spielberg’s office at Amblin Entertainment because it holds a great deal of meaning for the filmmaker.

“That painting spoke to me the second I saw it … and when I was able to buy it, I said, ‘Not only is that going in my collection, but it’s going in my office so I can look at it every day of my life.’ We are all on diving boards hundreds of times during our lives. Taking the plunge or pulling back from the abyss … it is something that we must face. For me, that painting represents every motion picture, just before I commit to directing it—that one moment before I say, ‘Yes, I am going to direct that movie,’ ” says Spielberg.

In the case of his Oscar-winning film Schindler’s List, Spielberg remarked, “I lived on that diving board for 11 years before I eventually took the plunge.”

Even in the creation of their work, Spielberg and Rockwell were more similar than is immediately evident. To create his meticulously detailed recollections of everyday American life, Rockwell worked much like a film director, not just acting out the scenes in his imagination, but scouting locations, casting everyday people from his town for particular parts, choosing costumes and props, and directing his performers to make them instantly familiar to the public. Little wonder then, that filmmakers like Spielberg and Lucas, as well as others, should be so inspired by his work.

In directing his own scenes, Rockwell had a specific focus, just not one based on the stark realism in which he grew up. Instead, Rockwell aimed to depict life in a kind of realistic fantasy. He later remarked in his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, “I paint the world not as it is, but as I would like it to be.”

© SEPS

This desire to “make” the real world a better place, at least in his images, was a sentiment that Rockwell would voice throughout his life. Eventually, he sought something of the idealized world he imagined, when he moved out of the city, first to New Rochelle, New York, then later settling in Vermont with his family. Rockwell found new models in the form of neighbors, as well as his children.

“All of us, my brothers, my mother, and myself, as well as our friends, served as characters in my father’s illustrations at one time or another,” says his son Tom, himself a writer, perhaps best known for his popular children’s book, How to Eat Fried Worms.

A study of Rockwell’s creative process reveals that composing each of his simple-to-understand works wasn’t simply a matter of grabbing whoever was handy and drawing them into a picture. In fact, each image was a highly involved endeavor requiring masterful ability as an illustrator and painter, as well as his unique skill to create “scenes” that would be instantly understood by the viewer.

“Everything I have ever seen or done has gone into my pictures in one way or another. The story of my life is really the story of my pictures and how I made them,” Rockwell said. “I store up things in my mind, and when I need something for a picture—a feeling, a character, a wry smile—there it is. And I draw it out and paint it.”

In the act of describing his work, Rockwell, the artist, embodied his characters, just as his work now embodies aspects of the American character that still strikes a chord, inspiring both other artists and Americans from all walks of life today.

The fact that Rockwell’s canvases are populated with such real-looking people is likely what gives them such resonance, making them believable. Still, there is something in the facial expressions that Rockwell not only captures, but exaggerates—youthful enthusiasm, boyish eagerness, pride, yearning, determination, and more—that transcends location, time period, and situation and makes the works both easy to connect with and ripe for repeated rediscovery, generation after generation.

In this context, Rockwell becomes as significant as any American artist has ever been, and can arguably be credited not only with recounting the American experience but to a large extent, with constructing the collective “memory” of the good old days that we still yearn for, whether we ever personally experienced them or not.

© SEPS.

Rockwell’s opinion of his work during his life was decidedly more humble, however. Certainly he was conscious of his role in the art world. He was an illustrator, not a modern artist or fine arts painter, and he had to satisfy not only himself, but his clients and audience alike. He needed to create scenes that people would get in a matter of seconds. He had to meet deadlines and stick to magazine proportions. And within those strict parameters, he wanted to convey this sense of idealized life. “I guess I had a bad case of the American nostalgia for the clean, simple country life, as opposed to the complicated world of a city,” he explained.

Rockwell’s insight and anything-but-easy process is itself the subject of a new, in-depth book, Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, by author and historian, Ron Schick.

“In order to ensure that every detail was perfect, Rockwell first used models and drew from life. Eventually, though, he switched to photographing his subjects in a variety of poses and with varying props, locations, and models. Every minute detail was deliberate, a means of convincing the viewer that they were eavesdropping,” says Schick, who describes Rockwell as a narrative artist with a Jeffersonian sense of America and its modest, everyday heroes.

“The world needed comfort, something to believe in, and Rockwell gave it to them in a way that people from all walks could understand,” Schick says. Understand, yes, but also be emboldened. The moments of inspiration that the artist captured, the tacit encouragement to move forward and celebrate life with all its challenges, setbacks, and triumphs—these ultimately may be Rockwell’s best legacy.

In a nation with cultures as disparate as ours, that Rockwell consistently managed to find patches of common ground for us to build on is a testament to his enduring work, not only for the generations of Americans who grew up seeing his art when it was new, but for future generations who are seeing Norman Rockwell’s America for the first time.

For more information, check out our Post retrospective Norman Rockwell and American Idealist Art.