Your Health Checkup: Vaping and Serious Lung Problems

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

I just returned from a family vacation in Positano, a charming seaside Italian village on the Amalfi coast built into the rugged cliffs that overlook the Tyrrhenian Sea … wonderful food, friendly people, and breathtaking landscapes. There were hundreds of stone stairs to climb between our villa and the beach, so I got my daily exercise dose! That, plus eating a Mediterranean diet, made for a healthy vacation.

Except for one shortcoming: smoke. Italy and many other European countries still harbor large populations of smokers, who now not only smoke cigarettes but also vape.

I wrote previously about the hazards of vaping in April and October of 2018, and stressed that the activity was associated with an increased risk for heart attacks. The surge in its popularity, particularly among young people, and the recently publicized pulmonary toxicity have prompted me to write about vaping again.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has noted a cluster of people — primarily adolescents and young adults — developing serious lung problems linked to the use of e-cigarettes. Almost 200 cases of severe respiratory illnesses related to vaping have been reported in 22 states in the U.S. All of the cases occurred in people vaping with either nicotine or tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the active chemical in marijuana responsible for the “high.” Often people vape with both nicotine and THC, making it difficult to determine which compound might be the culprit.

According to the CDC, in 2018 more than 3.6 million U.S. middle and high school students said they had used e-cigarettes in the past thirty days. More than a third of twelfth graders reported vaping in the past twelve months. The nicotine content in vaping can be much greater than that found in combustible cigarettes. Teenage brains appear particularly vulnerable to the addictive effects of nicotine, perhaps making them more susceptible to other kinds of substance abuse in the future.

Individuals developing lung problems start out with infectious-like symptoms. They complain of severe respiratory symptoms such as difficulty breathing and shortness of breath, often with fever, cough, chest pain, vomiting, headache, and fatigue. Those most seriously ill require hospitalization — sometimes in an intensive care unit — and treatment with oxygen. Some need intubation and spend days on a mechanical ventilator. Whether or how much of the lung damage is reversible is uncertain at present. Recently, one death from pulmonary failure associated with vaping was reported in an Illinois adult.

Numerous ingredients in the vaping aerosol in addition to nicotine and THC could be responsible, such as ultrafine particles, heavy metals like lead, volatile organic compounds, and cancer-causing agents. E-liquids include propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and more than 7,000 choices of chemical additives for flavoring, some of which have been tested for toxicity in the laboratory, while most have not.

Multiple counterfeit or adulterated products — some from China — have also entered the market, adding to potential risks because they can contain unknown and untested ingredients. Recently, more than 1150 fake Juul pods from China were seized in Philadelphia.

No consistency exists so far in terms of a common product or device responsible for the lung problems. Even though it is still uncertain whether vaping is definitively the culprit because the short and long-term risks associated with vaping are still being determined, the number of affected individuals who vape appears to be increasing, making a link likely.

What should you do? Stop vaping, of course. This will be difficult for many who are addicted to the nicotine ingredient in e-cigarettes. The development of chest pain, difficulty breathing, unexplained fever, or symptoms noted above should generate an immediate visit to a physician.

To paraphrase Paul Dudley White, a famous Boston physician, death before 80 years is man’s fault, not nature’s. Don’t tempt the fates with vaping.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com.

Are Cigarettes Going Away for Good?

The history of cigarettes in the United States is one of a great rise and fall, but will smoking ever completely die out?

Cigarettes were a tiny fraction of total tobacco consumption at the turn of the century, when chewing tobacco, pipes, and cigars were more popular. By 1930 — more than 40 years after the invention of the practical rolling machine — cigarettes had taken over, and by 1965, 42 percent of adults were smoking them. But a government report in the mid-sixties would spell the rapid decline of smoking in America.

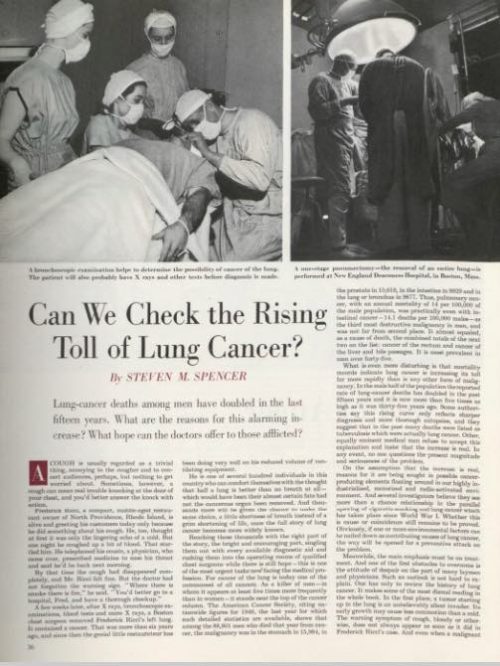

The U.S. Surgeon General’s report in 1964 dealt a permanent, heavy blow to tobacco sales, but it wasn’t the first consideration of the health effects of smoking. In 1950, this magazine explored whether the “cigarette cough” might be indicative of a causative link between smoking and lung cancer in the article, “Can We Check the Rising Toll of Lung Cancer?”

“Whether excessive cigarette smoking is a factor in the commonest form of lung cancer, squamous cell or epidermoid, is being warmly argued,” claimed author Steven M. Spencer after finding that 63 percent of lung cancer patients in a New York survey had smoked cigarettes 25 years or more. Lung cancer was quickly rising at the time — particularly among men — but the breadth of studies didn’t exist to prove that cigarettes were causing it.

Now it does exist, and the smoking rate among adults in the U.S. is down to 15 percent.

The fall of cigarettes in the U.S. could be regarded as an unparalleled victory in public health. “I don’t know of another area in which similar health improvements have been demonstrated,” says Dr. David Hammond, a public health expert from University of Waterloo. Yet despite the dramatic decline, smoking is still the leading cause of death in the U.S. It’s a case of simultaneous success and failure.

Although smoking rates have plummeted across the board, there are still some geographic, social, and economic indicators. The incidence of smoking is about four percent higher in the Midwest than the national average, five percent higher among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals, and more than 10 percent higher for people living under the poverty line. Hammond says, “The good news is that smoking has been going down across all socioeconomic strata; the bad news is that we haven’t narrowed the disparities that have been there for decades.” And narrowing those disparities is in the public interest, since the CDC estimates a loss of more than $300 billion each year due to smoking from direct medical care and loss of productivity.

There are tools for the public fight against cigarettes that have proven effective, like media and regulation on advertisements. Dr. Hammond says the U.S. could improve in other areas, particularly warning labels: “They’re probably among the weakest in the world,” he says, “and they haven’t changed since 1984.” The FDA has released stricter deterrent warnings to be used on cigarette packaging per the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, but litigation from tobacco companies — framed around First Amendment rights — has kept the reality of the new packaging standards at bay.

Another, more controversial, tool for quitting is the electronic cigarette. Like the prescribed medications for smoking cessation — nicotine patches, gum, and lozenges — e-cigarettes, or vaping, deliver nicotine to the user. The jury is still out on the long-term effects of e-cigarette use, but the harm is estimated to be somewhere between smoking and the aforementioned medications.

Vaping has been found to help smokers quit, but experts worry that it could attract young people to nicotine who never used it in the first place. Dr. Hammond co-authored a study in the Canadian Medical Association Journal regarding youth initiation to smoking and vaping. It found that “the causal nature of this association remains unclear” because of “common factors underlying the use of both e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes.” While they may not pose a high risk of being a gateway to tobacco use, e-cigarettes warrant more data. “We would be crazy if we weren’t keeping a close eye on the number of kids trying e-cigarettes, but to date it doesn’t seem to be increasing smoking,” according to Hammond.

A variety of approaches, in a variety of fields, seems to be the accepted strategy in taking down cigarettes, but what would victory look like? An absence of cigarette companies? Vaping as a new norm? It’s difficult to imagine that e-cigarette companies would cease to exist after completing the task of taking down big tobacco, but, unlike the latter, the vaping industry is less monolithic and represented by a variety of big and small interests. The conglomerated efforts of tobacco companies, after all, have put up the decades-long fight that continues more than 50 years after a report that probably should have buried the industry. There have been considerable public health triumphs, but the current 480,000 annual smoking-related deaths suggest that there is still a long road ahead.