Tiger Woods and More Triumphant Sports Returns

As Tiger Woods steps onto the grass at The Masters this week, the eyes of the sports world are upon him. Woods, returning from what many had thought was a career-ending accident, has defied the odds before. In 2019, Woods won The Masters after an 11-year drought at major tournaments. Could Woods make another thrilling return? In that spirit, here are five other returns by athletes that should never have been counted out.

Before we look at the Big Five, here’s a Bonus Two-for-One Special:

Bonus: Magic Johnson and Larry Bird

The Best of the Dream Team (Uploaded to YouTube by Olympics)

In 1992, Larry Bird of the Boston Celtics was on the verge of retirement. Plagued by back problems, he’d had a disc removed, missed 37 games during that season, and was headed out the door. His great friend and nemesis, Magic Johnson of the L.A. Lakers, had retired in 1991 after being diagnosed as HIV-positive. However, the two had a chance for one last run together: the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. Joining one of the greatest athletic teams ever assembled, Bird, Magic, and the rest of Team USA stormed their way to a gold medal. For basketball fans that had watched the pair battle from the 1979 NCAA Finals and through the entire 1980s in the NBA, well, that’s why they called it “The Dream Team.” While Bird did retire after the Olympics, Magic returned to the NBA as a player in 1996, helping the team get fourth seed in the playoffs. After the Lakers lost to the Rockets, Magic retired for good.

5. George Foreman

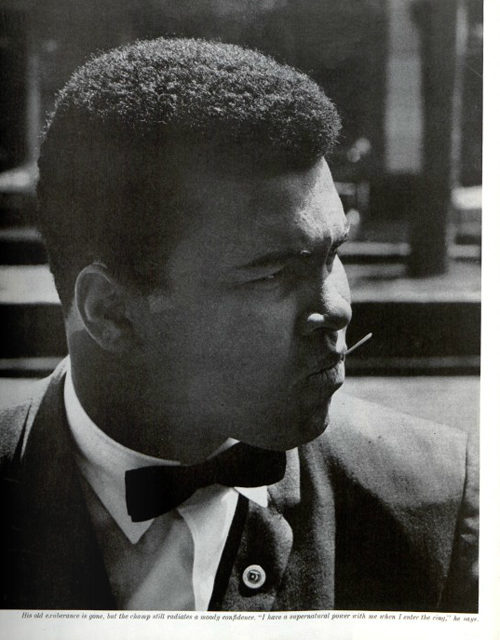

George Foreman in 1973 (Photo by Bert Verhoeff via Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

One of the best to ever lace up a pair of boxing gloves, George Foreman took gold in the 1968 Olympics as a heavyweight. Foreman went on to knock out an undefeated Joe Frazier to become heavyweight champ in 1973. His title reign came to an end at the hands of Muhammad Ali at 1974’s legendary “Rumble in the Jungle.” Foreman retired in 1977. After spending several years as a minister, Foreman came back to boxing in 1987. In 1994, the 45-year-old Foreman knocked out Michael Moorer to become the unified heavyweight champion. He remains the oldest man to be heavyweight champion.

4. Bethany Hamilton

This Iz My Story (Uploaded to YouTube by Bethany Hamilton)

Bethany Hamilton excelled at surfing from an early age. An avid competitor by age eight with sponsorships by age ten, Hamilton had her eyes on big titles. However, in 2003 when she was 13, the unthinkable happened. During a surfing excursion, a 14-foot long tiger shark bit off Hamilton’s left arm below her shoulder. It was a trauma that would have crushed most people, but not Hamilton. She returned to the waves a mere month after the incident. In 2005, she took first in the NSSA Nationals and won her first pro tournament in 2007.

3. Mario Lemieux

Lemieux Scored 100 Points 10 Different Times (Uploaded to YouTube by NHL)

There’s no debate about the greatness of Mario Lemieux. He’s widely regarded as one of the greatest hockey players ever. Lemieux debuted for the Pittsburgh Penguins in 1984 and quickly became a star. He was Rookie of the Year and was only outscored in his sophomore season by Wayne Gretzky. Though Lemieux would struggle with back injuries, he was a major force in the NHL as one of the sport’s biggest scorers. In 1993, “Super Mario” was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma. Undeterred, he continued to play, even on the same day as radiation treatments. Incredibly, he won the scoring title that year. Though he continued to play at a high level, the years of back problems and his earlier battle with cancer factored in to Lemieux’s decision to retire in 1997. With the Penguins facing money trouble, Lemieux came in with a plan to become the team’s majority owner. He helped turn things around the ledger, and then did something more incredible: he returned to the ice. Lemieux played from 2000 to 2006, ending his career with dozens of records and an Olympic gold medal from 2002.

2. Michael Jordan

The Best of Jordan’s Playoff Games (Uploaded to YouTube by NBA)

For Michael Jordan, an NBA championship wasn’t a question of “if,” but a question of “when.” Joining the league in decade dominated by the Celtics and the Lakers, Jordan turned around the fortunes of the Chicago Bulls. He led the team to a finals win in 1991, and then again in 1992 and 1993. Tragically, Jordan’s father, James Jordan, Sr., was murdered by carjackers in July of 1993. That October, Jordan retired, citing his father’s death, a loss of desire to play, and general exhaustion. After detour to play minor league baseball, Jordan issued a two-word press release (“I’m back”) and returned to the NBA in March 1995. He lifted the struggling Bulls into the playoffs, where they lost to the Orlando Magic. As the meme goes, Jordan took that personally. Over the next three seasons, Jordan led the Bulls to championships in 1996, 1997, and 1998, cementing his status as one of, if not the, greatest to ever play the game.

1. Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali – The Greatest of All Time (Uploaded to YouTube by Nonstop Sports)

How could The Greatest now be #1? Muhammad Ali’s life was defined by battle. Whether it was taking the Olympic gold medal in Rome in 1960 or taking his draft evasion conviction all the way to the Supreme Court, Ali never backed down from a challenge. After becoming champion in 1964, Ali voiced his opposition to the war in Vietnam and proclaimed his status as a conscientious objector. His titles were stripped, and Ali fought the decisions in court. The conviction was overturned in 1971 and Ali found himself in the position to challenge Joe Frazier for the heavyweight title. Both men were undefeated going in, but it was Ali that left with his first professional loss. Of course, that didn’t mean that Ali was done. He faced Frazier again in 1974, defeating his old rival to get a shot at the then-current champ, George Foreman. At the “Rumble in the Jungle,” Ali knocked out Foreman to retake the title. He would eventually retire in 1981, a three-time heavyweight champion

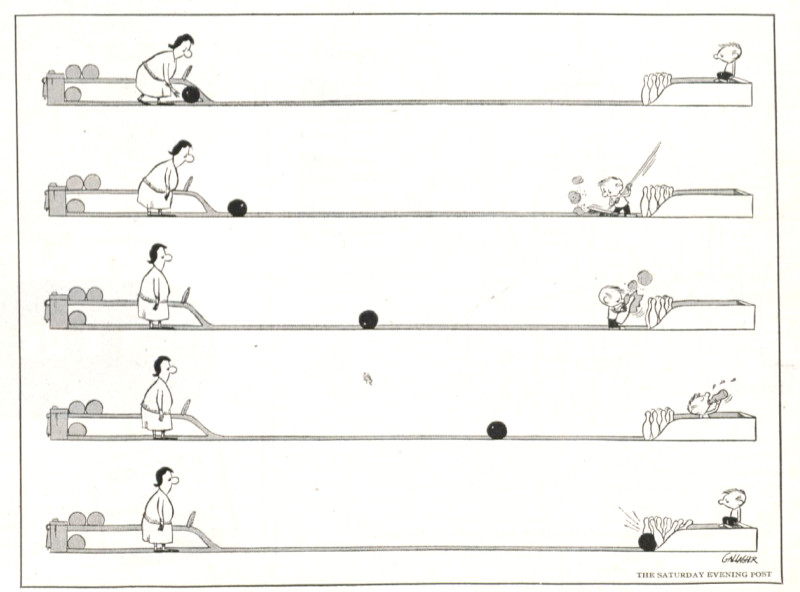

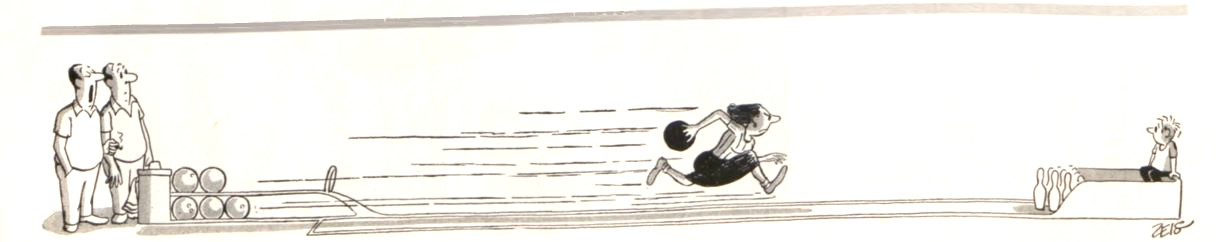

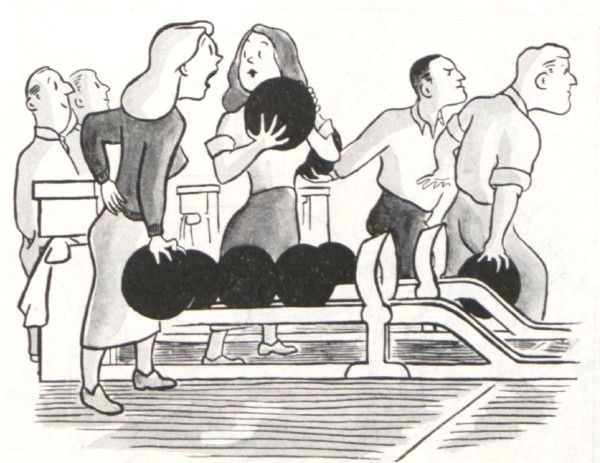

Cartoons: Bowling Is the Best!

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Wesley Thompson

November 15, 1952

O’Brien

November 12, 1955

Gallagher

November 5, 1955

Bob Barnes

September 17, 1955

Scott Brown

March 17, 1951

W.F. Brown

March 3, 1956

Eric Ericson

February 25, 1951

February 10, 1951

Zeis

February 9, 1957

Jane Sperry

November 17, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

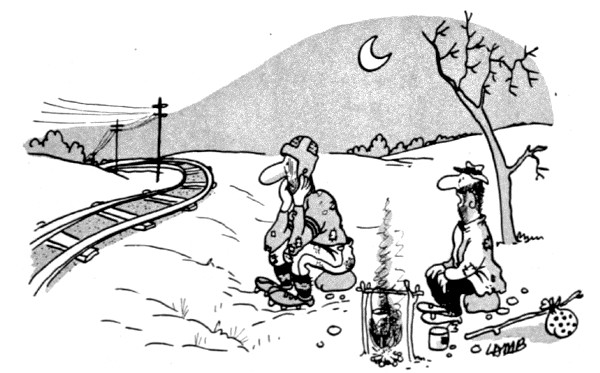

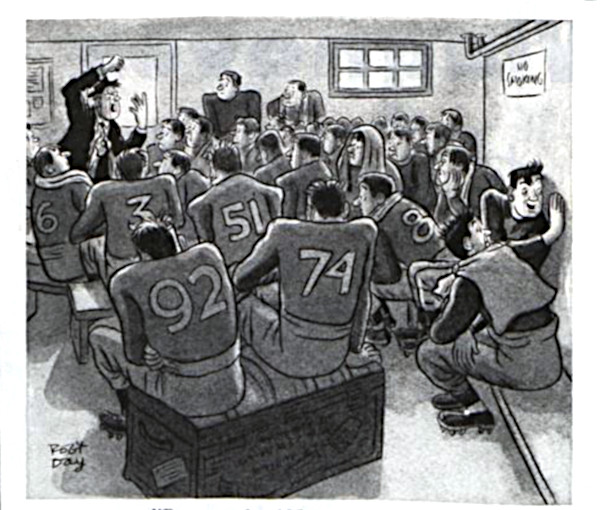

Cartoons: Pigskin Grins

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Lamb

November 27, 1954

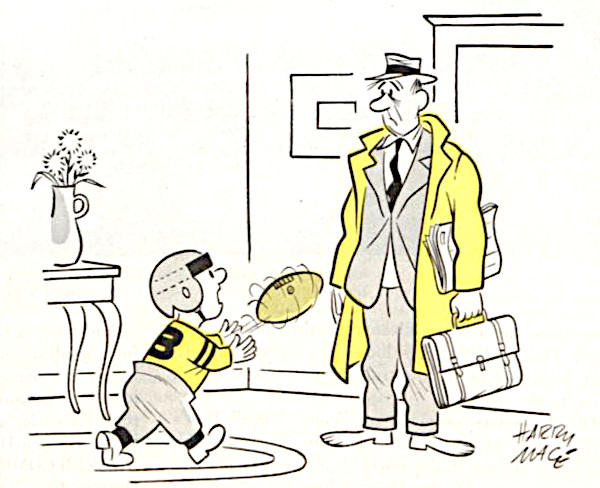

Harry Mace

November 15, 1952

November 1, 1980

Al Johns

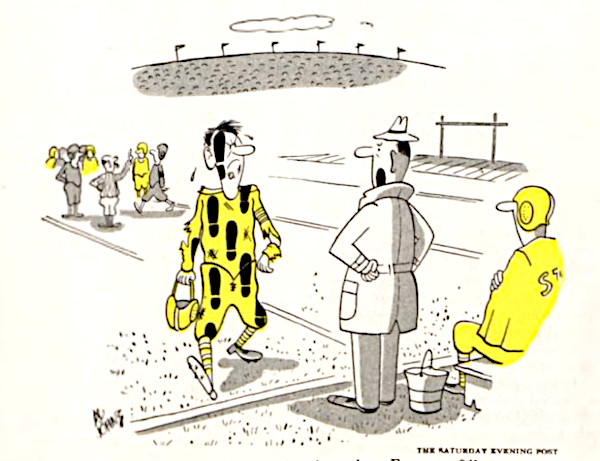

October 26, 1957

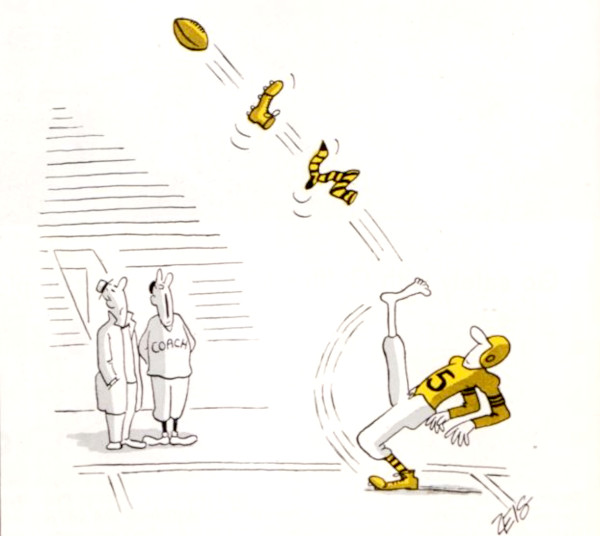

Zeis

October 25, 1958

Walter Wetterberg

October 25, 1952

Gallagher

October 16, 1954

Bernhardt

September 25, 1954

Roy Wilson

September 18, 1954

Ernie Garza

December 9, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

5 Things You Didn’t Know About Monday Night Football

Monday Night Football kicked off 50 years ago this week. The broadcast was a crucial component in establishing the NFL as a dominant ratings force and making it the most-watched sporting league in the United States. Prior to its move to ESPN in 2005, MNF was one of the longest-running prime-time shows in the history of network TV. With a new season underway, here are five things you didn’t know about Monday Night Football.

1. It Has Hosted More Than 700 Games

Throughout the 50 seasons of Monday Night Football, the series has played 718 games as of September 21, 2020. The very first game saw the Cleveland Browns host the New York Jets. The Browns won 31-21 in a game that was watched by 33 percent of the total American viewing audience for that evening.

2. Gifford Had the Chair Longer Than Anyone

Howard Cosell remains the most famous original commentator; he held his spot for 13 years. Frank Gifford joined in the second season, and his run lasted until 1998, making him the commentator who was with the show the longest with a total of 27 years. There have been about 40 play-by-play announcers and color commentators across the history of the program on ABC and ESPN; the current team consists of Steve Levy, Brian Griese, and Louis Riddick. There have been dozens of sideline reporters and more than a dozen radio commentators; the current radio team is Jim Gray, Kevin Harlan, and Kurt Warner.

3. Famous Guests Have Hit the Booth

Over the years, a number of celebrities dropped by the broadcast booth. Visitors have included Kermit the Frog, Richard Nixon’s first vice-president Spiro Agnew, and President Bill Clinton. On December 9, 1974, both John Lennon and Ronald Reagan were in the both at the same time. Sadly, just six years later on December 8, 1980, Lennon was shot and killed in New York City. Cosell broke the news to most of America near the end of a Monday Night game between the New England Patriots and Miami Dolphins.

4. It Took Over American Sports and Went Global

MNF was firmly entrenched in the Top Ten of the weekly broadcast ratings for years, becoming one of the most popular shows in America. It elevated football to the position of the most-watched sport of the big three in the States, dethroning Major League Baseball as the favorite and holding off NBA basketball even at its biggest. The show is carried in Europe, Australia, and South America. ESPN has American broadcast rights, including streaming, through 2021. As of August, ESPN is looking to improve the deal for an extension.

5. Monday Night by the Numbers

The most-watched game ever was the Miami Dolphins versus the Chicago Bears on December 2, 1985. The Dolphins ruined the Bears’ shot at a perfect season, handing them their only regular season loss; the Bears would go on to win the Super Bowl (while, one presumes, doing the “Super Bowl Shuffle”). The Dolphins, however, take the title of Most MNF appearances (their 85th appearance is this season). The highest scoring game ever was in 1983 when the Green Bay Packers and the now-titled Washington Football Team ran up a combined 95 points.

The full “Monday Night Miracle” game (Uploaded to YouTube by the NFL)

MNF has been the stage for some amazing comebacks. One of the most popular came in 2003 when the Indianapolis Colts were down 35-14 against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Colts quarterback Peyton Manning engineered a comeback with four minutes left on the clock to tie the game; Colts kicker Mike Vanderjagt kicked a winning field goal in OT, giving the Colts a 38-35 win. However, only one game is called the “Monday Night Miracle,” and that honor goes to the October 23, 2000, game between the Jets and the Dolphins. The Jets scored a seemingly impossible 30 points in the fourth quarter, tying the game and sending into OT; when it was all over, the Jets had squeaked by 40-37.

Featured image: pixfly / Shutterstock

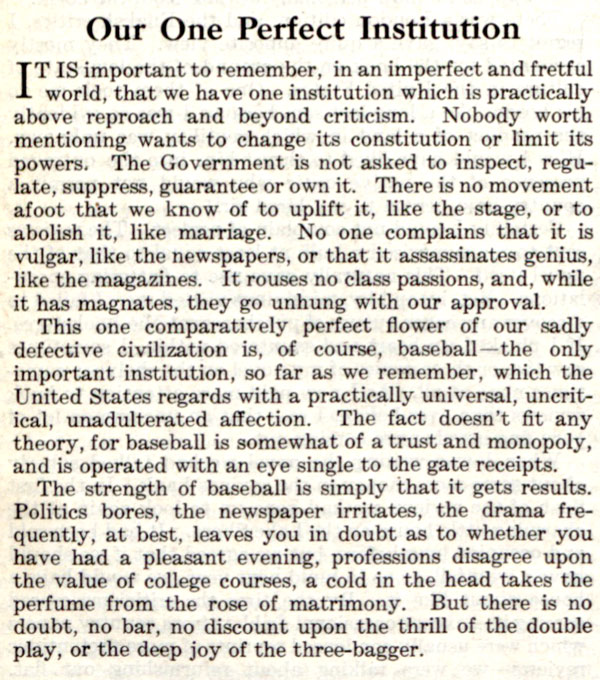

Baseball: Our One Perfect Institution

In 1908, the game was untarnished by cheating scandals and drug abuse. The top ballfield heroes were Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner, and the new song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” became a hit. With the World Series just ended, the editors looked back on the past season with satisfaction and pride in the national pastime.

In an imperfect and fretful world, we have one institution which is practically above reproach and beyond criticism. There is no movement afoot to uplift it, like the stage, or to abolish it, like marriage. No one complains that it is vulgar, like the newspapers, or that it assassinates genius, like the magazines. It rouses no class passions, and, while it has magnates, they go unhung with our approval.

This one comparatively perfect flower of our sadly defective civilization is, of course, baseball — the only important institution that the United States regards with a practically universal, uncritical, unadulterated affection. The fact doesn’t fit any theory, for baseball is somewhat of a trust and monopoly and is operated with an eye to the gate receipts.

The strength of baseball is simply that it gets results. Politics bores, the newspaper irritates, the drama frequently, at best, leaves you in doubt as to whether you have had a pleasant evening, a cold in the head takes the perfume from the rose of matrimony. But there is no doubt, no bar, no discount upon the thrill of the double play, or the deep joy of the three-bagger.

—“Our One Perfect Institution,” Editorial, October 31, 1908

The Saturday Evening Post

October 31, 1908

Featured image: Robert Robinson / SEPS

Review: A Most Beautiful Thing — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

A Most Beautiful Thing

⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Run Time: 1 hour 35 minutes

Narrator: Common

Director: Mary Mazzio

Now streaming on XFinity VOD; on Peacock September 1; on Amazon Prime October 14.

The best documentaries lull you into thinking they’re taking you for a nice float on a lazy stream — then abruptly suck you into a chasm of Class 5 rapids that have you holding on for dear life.

That’s the kind of ride we get in director Mary Mazzio’s new film, which starts out as the inspiring tale of America’s first all-African-American public high school rowing team — but has much more on its mind than warm feelies.

It’s the 1990s on the West Side of Chicago, where gang violence is tearing apart the student body of Manley High School. Enter a white Chicago businessman named Ken Alpart, who naively convinces administrators that what the school really needs is a rowing team. He puts a sleek crew shell on display in the cafeteria, offers free pizza to anyone who signs up — and waits to see who comes through the door.

What he gets is a random collection of rival gang members, kids barely holding onto their lives, much less their grades. We meet them in the present day: Grown men, now nearly 40, scarred by their harrowing youths. Foremost among them is Arshay Cooper, who recalls for us his daily adventure walking five blocks to school — and having to wear his baseball cap a different way each block, so as not to get jumped by the local street gang.

The guys laugh as they recall their first time sitting in the low, easily-tipped boat — terrified they might end up in the water.

Some were ready to quit before they got started until, as Cooper recalls, he asked them, “How can you deal with gunshots all day long in your neighborhood and you’re scared to sit in a boat?”

From here the narrative seems to be going just as we’ve hoped: On the water, the guys find a peace they’ve never known before. The former sworn enemies become a team. They enter their first competition, fail miserably, but learn from their mistakes. Finally, at the biggest race of the year, they not only earn the respect of other rowers, but they are celebrated by the entire city of Chicago.

It’s an engaging, feel-good story that seems tailor made for a Hollywood remake — you could probably do the casting yourself.

But something seems a little off here: We’re barely halfway through the film’s run time, and the kids are already graduating from high school. They say farewell to their rowing adventure. Everyone goes their separate ways.

Now what?

It is now 2018, and the old teammates have just learned that an assistant coach from their high school days has suddenly died. They gather for the funeral, and Cooper hatches an audacious plan: Why not have a reunion row? It doesn’t take long for everyone to get on board with the idea.

It’s a decision that makes the second half of A Most Beautiful Thing even more inspiring than the first. For one thing, virtually none of the guys is anywhere near rowing shape. For another, it goes without saying none of the kids went on to Ivy League rowing glory; they returned to the ’hood where the familiar litany of misfortune awaited many of them: drugs, crime, poverty, and imprisonment. Skillfully and respectfully, Mazzio unfolds each man’s history, exploring the inner city dynamics that stacked the deck against them from the start (she cites a study that reports children from neighborhoods like these suffer higher rates of PTSD than combat soldiers).

Still, after a rocky start, the old teammates rediscover their rhythm. Cooper — who wrote the book on which this film is based, is a sought-after motivational speaker and has become something of a legend in the rowing community — even enlists Olympic rowing coach Mike Teti to whip them into shape.

But Cooper has more than a rowing reunion in mind. Recalling how the sport brought gang rivals together, he hatches an outrageous notion: Why not invite four members of the Chicago Police Department to row with them?

Now, Mazzio has just spent the last hour or so illustrating the tortured relationship between the cops and the ’hood. At this very moment, one of the guys is wearing an ankle bracelet after a run-in with the law. But they trust Cooper and reluctantly agree, leading to some of the most remarkable scenes of awkwardly effective bridge building you’ll ever see.

Finally, the team decides to enter one last official race, returning to the waters where they found high school glory. By now we’re beyond worrying about whether they’ll win or lose. We’re all friends here.

It’s hard to imagine a more stormy sea than the one this country is navigating right now, but the inspiring men from Manley High School have a couple of lessons for us all: First, don’t assume that everyone who’s not on your side is your enemy. And second, it’s possible to find common cause with just about anyone, even if you have to keep them at oar’s length.

Featured image: Richard Schultz/50 Eggs Films

Caddyshack Turns 40: Nine Things You Didn’t Know About the Cinderella Story

EPSN thinks it might be the funniest movie ever made about sports. Some point to it as another example of how Saturday Night Live incubates talents that are suitable for the big screen. And others consider it the best of the “slobs vs. snobs” subgenre of comedy. However you score it, Caddyshack has been one of most popular and most loved film comedies (almost) since its release 40 years ago this week. In honor of its longevity and continued hilarity, we’ll shoot a (front) nine full of things you didn’t know about Caddyshack.

1. It Was Created by Caddies

Caddyshack star Bill Murray is regular on the Celebrity Pro-Am circuit (Uploaded to YouTube by PGA Tour)

Writer and co-star Brian Doyle-Murray had the idea for the film based on his own experiences working as a caddie. His brothers John and Bill Murray had as well, as had their friend Harold Ramis. Brian, Bill, and Ramis had all been members of the Second City comedy troupe; Ramis also worked with Bill Murray on The National Lampoon Radio Hour and was one of four writers credited on Murray’s film, Meatballs. Douglas Kenney, who had founded National Lampoon magazine and co-wrote National Lampoon’s Animal House with Ramis and Chris Miller, came aboard and collaborated with Ramis and Doyle-Murray on the screenplay for Caddyshack. In 2002, the Murrays and their fourth brother, Joel, created and appeared in the Comedy Channel series The Sweet Spot, which featured the brothers playing golf at top-notch courses.

2. What Ramis Really Wanted to Do Was Direct

With his background writing for SCTV, National Lampoon, and two successful screenplays under his belt, Ramis was able to assume the director’s chair. Doyle-Murray took the role of caddie supervisor Lou Loomis, while Kenney would take a background role as one of Al Czervik’s (Rodney Dangerfield) hangers-on. The small scale of Kenney’s role was similar to his turn as Stork in Animal House, which he assigned himself and where he had only two lines; he’s the one who ultimately leads the marching band into a dead end. Brian and Bill’s brother John pulled double-duty on the film, appearing as a caddie extra and working behind the scenes as a production assistant.

3. Chevy Chase Was a Logical Fit

The “Be the Ball” Scene (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

Although Chase had passed on the role of Otter in Animal House (which was played by Tim Matheson), he agreed to join Caddyshack. Kenney was one of his closest friends, and he’d worked with Ramis and Bill Murray on The National Lampoon Radio Hour. An original member of the Saturday Night Live cast, Chase had also been the first to leave and find film success. By the time that he shot Caddyshack, he’d already had a hit with Foul Play. For his part, Murray was still on the show and would work shooting his scenes in the film around his SNL schedule. Doyle-Murray was also still working for SNL as a writer and would later be a full cast member.

4. There Are Too Many Palm Trees in Florida

Production began in the fall of 1979. Rolling Hills Country Club in Davie, Florida served as the location for the shoot; today it’s called Grande Oaks Golf Club. Ramis chose that location because it was one of the few Florida courses that didn’t have palm trees. The director was particular about that because he wanted the movie to feel like it could be in the Midwest. One downside of shooting in Florida was that the production had to contend with delays caused by Hurricane David, which briefly touched Florida on September 3.

5. The Film Made Rodney Dangerfield a Movie Star

Rodney Dangerfield was already established as a stand-up comedy star before Caddyshack. Dangerfield broke out after an appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1967. He would regularly return to that show and became a popular guest on programs like The Dean Martin Show and The Tonight Show (where he was a guest 35 times). In 1969, he and Anthony Bevacqua created Dangerfield’s, a comedy club in New York, which became one of the home bases of HBO’s Young Comedian Specials. Dangerfield’s stand-up background and Chase and Murray’s grounding in sketch comedy made them all quick on the draw with improv, an environment that led to their roles getting expanded and improvised bits (like Murray’s flower-destroying fantasy monologue about playing at Augusta) making the final film. For his part, Dangerfield was launched into leading his own film comedies like Easy Money.

6. We Should Probably Get These Two Together

The “Mind If I Play Through?” Scene (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The movie was already shooting when Ramis realized that two of the biggest draws in the film, Chase and Murray, had exactly zero scenes together. That may not have entirely been by accident, as Chase and Murray had famously had a contentious run-in backstage at SNL when Chase had returned to host the show. Nevertheless, Ramis, Chase, and Murray went to lunch together and worked out the scene where Ty Webb (Chase) plays a late-night round through groundskeeper Carl’s (Murray) place.

7. The Gopher Has Some Star Wars in Him

John Dykstra won an Academy Award for special effects work that he did for Star Wars, but he had already been famously pushed out of Industrial Light and Magic by George Lucas for budget and scheduling issues before that film was finished. Dykstra would go on to create special effects for a number of other high-profile projects, including the original pilot and theatrical film for Battlestar Galactica. Dykstra’s team created the gopher and his lair while also handling lightning and other visual effects in the film.

8. The Kenny Loggins Film Reign Begins Here

Kenny Loggins performing “I’m Alright” (Uploaded to YouTube by Kenny Loggins)

Kenny Loggins was already a music mainstay before Caddyshack. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band did four of his songs in the 1970s, which is also when he formed his hit duo with Jim Messina. Loggins and Messina did seven albums in five years. He co-wrote the Doobie Brothers hit “What A Fool Believes” and wrote “I Believe in Love,” which Barbra Streisand sang in 1976’s A Star is Born. He contributed “I’m Alright” to the Caddyshack soundtrack, and it was used as the main theme of the film (and for the gopher’s memorable dance outro). He earned the nickname “The King of the Soundtrack” for his film work throughout the 1980s, which included hit songs for Footloose, Top Gun, Over the Top, and the less-said-the-better Caddyshack II: Back to the Shack.

9. The Hard Road to Classic Status

Harold Ramis on Caddyshack 30 Years Later (Uploaded to YouTube by American Film Institute)

The film was financially successful, but critics weren’t too kind. However, fans embraced it and it went on to an even bigger second life on cable and video. Critics reevaluated the movie over time as they realized how deeply funny and quotable it was. Bill Murray and Harold Ramis (on camera this time) reteamed the next year in Stripes, which was an even bigger success; Murray and Ramis did three more films together: Ghostbusters, Ghostbusters II, and Groundhog Day. Chase had major successes for the rest of the decade, including Fletch and three films in the National Lampoon’s Vacation franchise. Today, Caddyshack is regarded as a comedy classic and regularly places on lists of the American Film Institute, such as 100 Laughs and 100 Movie Quotes. The Murray brothers also own the Murray Bros. Caddyshack restaurants, two of which are still open in St. Augustine, Florida and Rosemont, Illinois.

Featured Image: Bill Murray attends Isle of Dogs New York special screening at Metropolitan museum on March 20. 2018. (lev radin / Shutterstock.com)

Considering History: The Washington Redskins, Oklahoma Territory, and the Myth of the “Vanishing Indian”

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

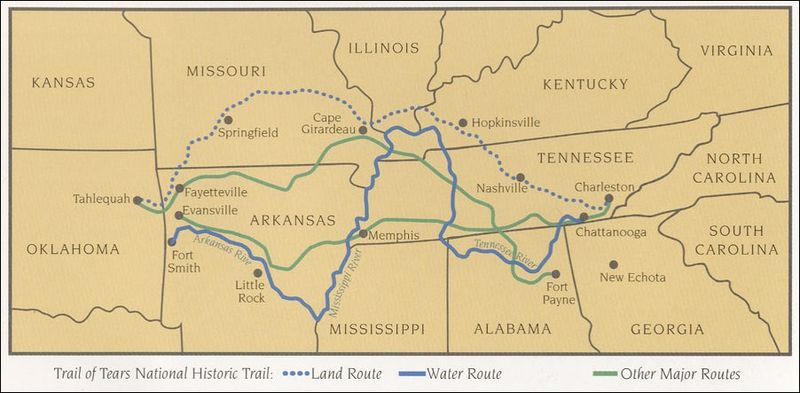

Recently, we have seen two striking decisions on longstanding issues connected to Native American communities. On July 9, in one of its last announced decisions of this session, the Supreme Court ruled that the eastern half of the state of Oklahoma remains “Indian territory” under 19th century treaties that guaranteed the land for tribes forced west on the Trail of Tears, treaties that have never been amended by Congress and so (the Court ruled) continue to hold today. And on July 13, the NFL franchise the Washington Redskins formally announced that the team will be changing its nearly century-old racist name and logo.

The details of these two decisions are quite specific to their respective arenas, and reflect evolving conversations in each case. But taken together, they exemplify two longstanding and contrasting national narratives: those which depict Native Americans through reductive, stereotypical images in order to justify attempts to expel and destroy native communities; and those which recognize instead Native Americans’ foundational and continued presence within America.

In order to justify his proposed, genocidal Indian Removal policy which produced the Trail of Tears, President Andrew Jackson depicted Native Americans through such stereotypical and racist imagery, defining them as savages unable to coexist with European-American communities or indeed exist at all within the expanding Early Republic United States. In his December 1829 first President’s Annual Message to Congress, Jackson argued that “this fate [disappearance] surely awaits them if they remain within the limits of the States.” And in his December 1833 fifth annual message, Jackson went much further, claiming, “That those tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens is certain…Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”

Jackson’s more aggressively racist depictions of Native Americans were complemented by a gentler and more insidious exclusionary perspective that came to be known as the “Vanishing Indian” narrative. Often advanced by figures and communities sympathetic to native rights, this narrative relied on images like the admirable but doomed “Noble Savage” to depict Native Americans as tragically but inevitably disappearing from the continent. James Fenimore Cooper’s bestselling historical novel The Last of the Mohicans (1826) illustrates this trope, arguing from its title on that its heroic Native-American characters are the “last” of a tribe that in fact still existed in Cooper’s era (and still does in our own). Poet Lydia Huntley Sigourney’s “Indian Names” (1834) is even more striking, as Sigourney uses the persistence of Native-American names on the American landscape to angrily (and inaccurately) lament the destruction of native communities: “Ye say they all have passed away,/That noble race and brave/… But their name is on your waters,/Ye may not wash it out.”

The “Vanishing Indian” narrative became a dominant trope across the 19th century and into the 20th, and in subtle but significant ways informed numerous prominent cultural works, as illustrated by Wellesley Professor Katharine Lee Bates’s 1893 poem “America” that became the lyrics for the song “America the Beautiful” (1910). That trope is most apparent in Bates’s second verse, where she describes America’s origin point: “O beautiful for pilgrim feet/Whose stern, impassioned stress/A thoroughfare for freedom beat/Across the wilderness!” But Bates likewise disappears Native Americans from the idealized images of the national landscape with which her poem opens, and which were inspired by a cross-country train trip from her Massachusetts home to a summer teaching job in Colorado. Bates originally named her poem “Pike’s Peak,” as she wrote it after a day trip ascending the mountain — but, like that name itself, her poem leaves no place for the Ute and Arapaho tribes who had been part of that landscape long before explorer Zebulon Pike arrived.

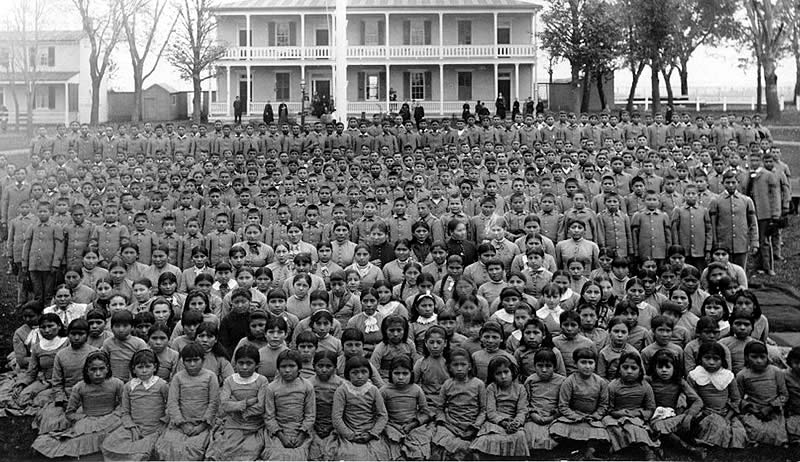

Bates’s 1893 trip took place just two-and-a-half years after the December 1890 Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota, an exemplification of the far more violent exclusionary attacks upon Native-American communities that continued throughout the 19th century. The late 19th and early 20th century also featured another, even more insidious form of cultural genocide designed to facilitate the disappearance of Native-American cultures: the boarding school movement, which (as Carlisle Indian Industrial School founder and former “Indian Wars” Captain Richard Pratt put it) was intended to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” Both these military and educational efforts illustrate that the “Vanishing Indian” was not just a cultural image, but also and most importantly an ongoing white supremacist goal.

As I wrote in this October 2018 Considering History column, Native-American activists and communities have consistently used legal and political means to challenge such attacks and advocate for their survival and their rights. In response to Jackson’s Indian Removal policy the Cherokee nation did so forcefully, with the tribe’s leaders drafting a series of “Cherokee Memorials” to the U.S. Congress that were published in the tribe’s newspaper The Cherokee Phoenix and submitted to Congress to request their assistance. The Cherokee also took their claims to the court system, and the Supreme Court sided with their rights to their land in the Worcester v. Georgia (1832) decision. Jackson famously ignored the Court and proceeded with removal.

Native-American legal and political efforts continued for the next century-and-a-half, including the two prominent moments I highlighted in my earlier column: Ponca Chief Standing Bear’s legal challenge which resulted in the groundbreaking 1879 decision that “an Indian is a person” for purposes of the law (and otherwise); and the numerous activists, including Zitkala-Ša and Nipo Strongheart, whose advocacy led to the watershed 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

The 1960s and 1970s American Indian Movement, founded in Minneapolis in 1968, continued to utilize the political and legal system to advocate for native lives and rights, while fostering the Red Power and Native-American Renaissance cultural movements of late 20th century America.

These destructive myths and their effects have endured, as illustrated by the horrifically high numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths on Native-American reservations — one more way (among too many, including the kidnappings and murders of native women and the destruction of native lands for pipeline construction) in which native communities continue to face the threat of disappearance. But the Supreme Court decision embodies a perspective in which Native-American rights and presence are seen and supported, and where native communities are defined as foundational and integral parts of America’s history, identity, and future.

Featured image: The delegation of Sioux chiefs to ratify the sale of lands in South Dakota to the U.S. government, December1889 / photo by C.M. Bell, Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)

A Black Champion’s Biggest Fight

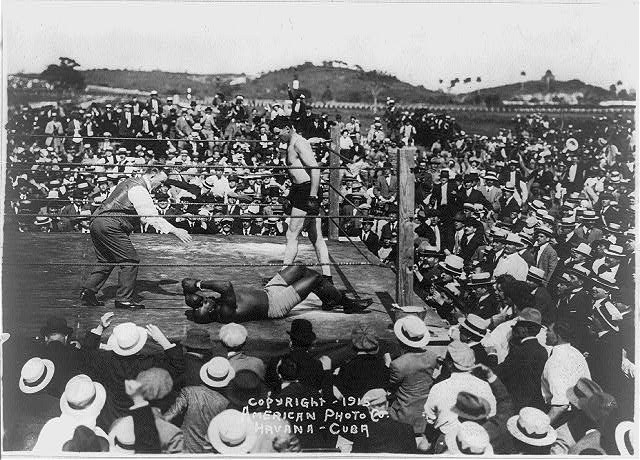

The prize fight held on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada was hailed “the Fight of the Century.”

In fact, it was just part of a fight that has been as long as our country’s history.

On that date, African-American champion Jack Johnson was defending his title against Jim Jeffries, as well as defending his race against a racist opponent. His victory detonated America’s first national race riot.

Seven years earlier, Johnson had won the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World.” He then achieved what no black athlete had done before: secured a chance to take a championship title from a white athlete. He boxed and defeated Canadian Tommy Burns for the world heavyweight title.

Johnson’s win challenged the racial superiority assumed by many white Americans. Sports writers and white fans called out for a “great white hope,” a heavyweight boxer who would re-assert white supremacy in the ring. When former champion Jim Jeffries agreed to fight Johnson, he publicly said his intention was “to win the title back for the white race.” And “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.”

The need to beat Johnson was made even more urgent because of his personality. He was flamboyant, proud, lived lavishly, drove recklessly, and had affairs with white women. So when he climbed into the ring in Reno, Johnson could sense waves of resentment rising from the crowd of 22,000 spectators. Jeffries even refused to shake his hand before the match.

Jack Johnson vs James J. Jeffries (uploaded to YouTube by Classic Boxing Matches)

Twenty-five years later, in an article from the August 3, 1935, issue of the Post, Jeffries said he trained intensively for a year-and-a-half before the match. He got back into shape and dropped his weight from 285 to 220. But just days before the match, he caught a severe case of dysentery that kept him from putting up his best fight. But there was no talk of illness in the days following the match. Then, Jeffries said, “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.”

White boxing fans who had made the match a contest of the black and white races felt humiliated and angry. They took the fight from the ring into the streets of American cities.

It was not a good year for race relations in America. At least 67 black Americans were lynched in 1910. The Keokuk, Iowa, newspaper that carried the news of Johnson’s victory also featured a front-page story about the black population of Charleston, MO, fleeing the city after two black men were lynched in the street by a gang of white men.

That same paper reported race riots broke out in 50 American cities following the news of Jeffries’ defeat. In New York, according to the Daily Gate City, 11 different racial brawls were reported on the night of the Fourth. Crowds, the paper reported, tried to burn tenements in black neighborhoods. African Americans were dragged from trolley cars in several locations by white rioters and beaten.

In Columbus, Ohio, white spectators repeatedly set upon 400 black men and women who were marching in a parade celebrating Johnson’s win.

A black man buying a newspaper was accosted by a mob, who demanded he tell them what he thought of the fight. “I am neutral,” the man replied. “Let’s kill the [racial epithet],” someone said and the gang approached him. He pulled a knife and held them off until the police arrived.

One reason for the attacks was the fear that African Americans would abandon the deference they were expected to show for the racial majority. A New York Times editorial written two months before the fight stated, “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbors.”

For some white fans, this championship bout ruined the sport. Eight years later, a humorous note in the October 6, 1923, Post observed, “The papers have been full of the news of prize fights. There must be some mistake about it. As nearly everybody knows, the boxing game in this country died when Jack Johnson whipped Jim Jeffries. It was repeatedly and authoritatively stated there never would be another prize fight.”

Five years later, Johnson was defeated by Jess Willard, a white boxer. Many white boxing fans were exultant. The book Jess Willard: Heavyweight Champion of the World described the aftermath: A sports writer for the St. Louis Times reported, “thousands and thousands of fight fans as well as thousands and thousands of ordinary citizens flooded the downtown streets waiting for the decision.” When they heard Willard had won, “they acted like crazy people.” According to the New York Tribune, the news prompted “respectable business men [to pound] their unknown neighbors on the back and [caper] about like children.”

In a May 8, 1915 editorial, the Post observed, “Critics seem quite unanimously of opinion that this event… is a thing of high importance to the white race. They seem, also, quite unanimously of opinion that Mr. Johnson would have beaten his white antagonist handily if he had not for some years followed an injudicious and deleterious mode of living. We are puzzled to discover a cause for racial pride in the circumstance that a white man was able to whip a black man only after the latter had impaired his constitution by dissipation.”

Three years before the match with Willard, while he was still champion, Johnson had been arrested and charged with violating the Mann Act for driving his white girlfriend “across state lines for immoral purposes.” Johnson fled the country to escape prosecution, which was why his fight was Willard was held in Havana, Cuba.

For years, the rumor persisted that Johnson threw the match, agreeing to take a fall in return for having the charges dropped. Johnson himself contributed to the stories, insisting that he had pretended to be knocked out as part of a deal with the government to drop its charges against him.

But writing for the Post in the April 4, 1925, issue, former heavyweight champion James J. Corbett said of the Johnson-Willard fight, “I was quite near the ringside and watched Johnson closely, and I am morally certain he would never have gone through twenty-six long rounds had the result been prearranged; he would have chosen an earlier round to flop in.” Agreeing with Corbett, Willard said, “If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he’d done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there.”

But the rumor never stopped hounding Johnson. In the 1940s, having spent a year in jail for the Mann Act violation, he was reduced to boxing in private events. He then got the idea for another way to raise cash, and went to the editor of the boxing magazine Ring, Nat Fleischer.

Fleischer knew Johnson. He had been at ringside when Johnson fell. According to a March 16, 1946 Post interview with Fleischer, “Johnson went down under big Jess Willard’s blows in the twenty-sixth round, rolled over on his back and raised an arm to shield his eyes from the tropical sun as he was counted out.” The arm-raising incident was cited as proof that Johnson had gone into the tank for Willard. Fleischer, convinced that the bout was fought on its merits, always argued that even a semiconscious man would instinctively try to shield his eyes from the blinding rays of the sun.

Despite Fleischer’s certainty of Johnson’s integrity, the Post reported that, “Johnson came to Fleischer with a signed confession stating that he had ‘gone into the water’ for Willard. Nat paid him $250 for it, after the ex-champion had signed an agreement giving him the exclusive rights to publish the story. Fleischer put the document in his safe, where it has since gathered mildew. Fleischer says Johnson has since tried to buy back the ‘confession,’ because he can get a better price for it elsewhere.”

Nat refused to sell. He didn’t believe a word of it, and chose not to publish the confession to protect a boxer, and a sport, that he revered.

In 2018, 72 years after his death, Johnson finally received a presidential pardon for his violation of the Mann Act.

Featured image: Jack Johnson and James Jeffries in 1910 (Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress)

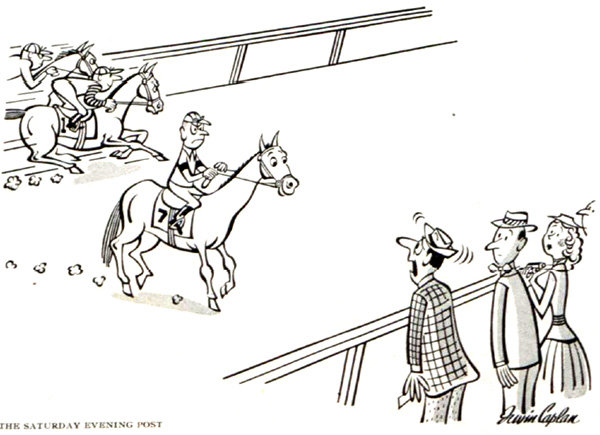

Cartoons: Horsing Around

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Reginald Hider

October 6, 1951

Irwin Caplan

August 16, 1952

Goldstein

July 31, 1954

Chon Day

June 9, 1951

Gallagher

April 24, 1954

Frank O’Neal

April 19, 1955

Shirvanian

October 13, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

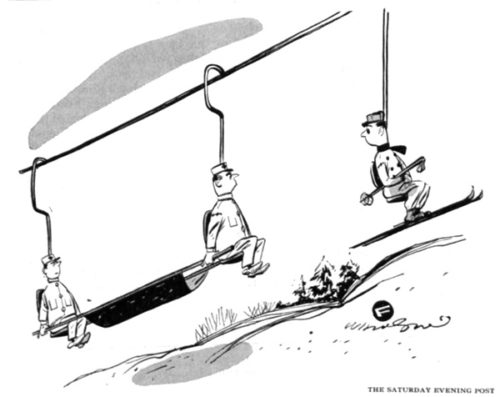

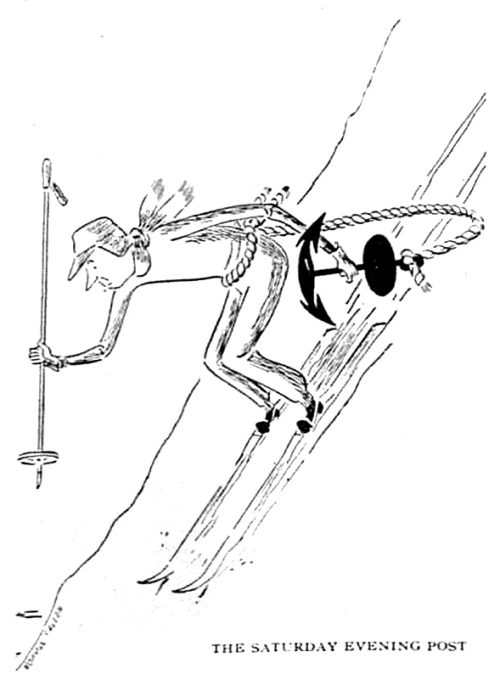

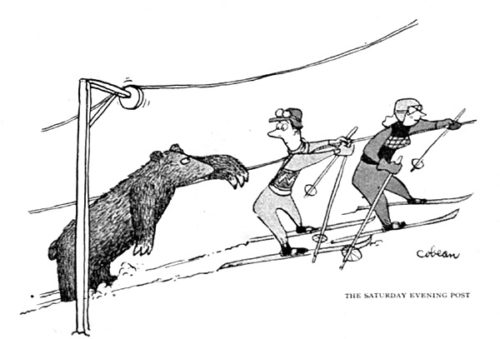

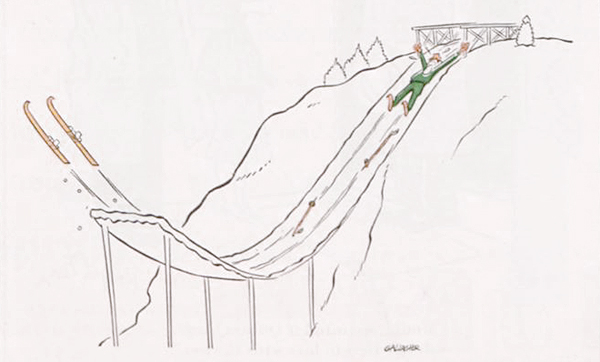

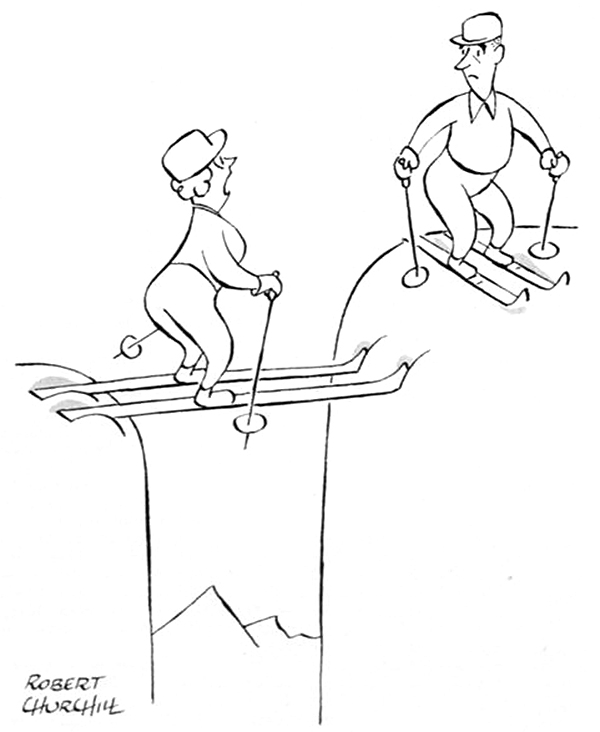

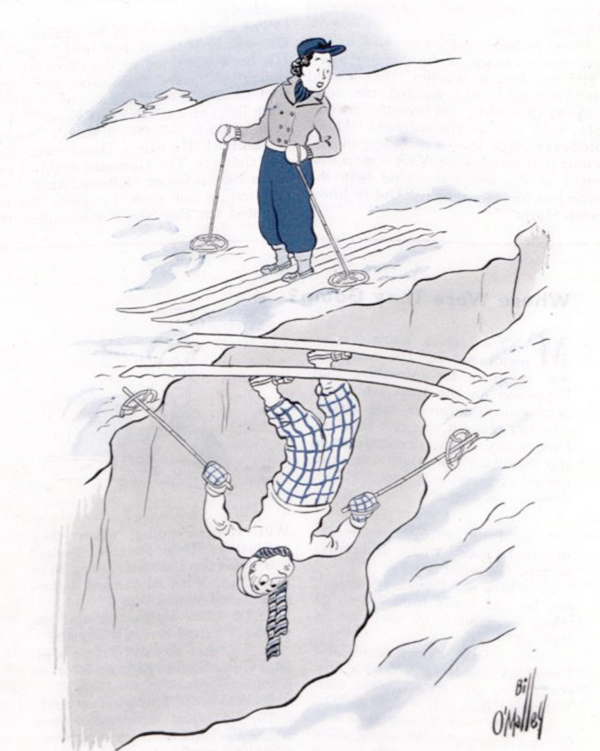

Cartoons: Ski-lightful

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

November 27, 1954

November 19, 1955

August 12, 1944

January 30, 1954

Robert Churchill

January 27, 1951

Bill O’Malley

January 13, 1945

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

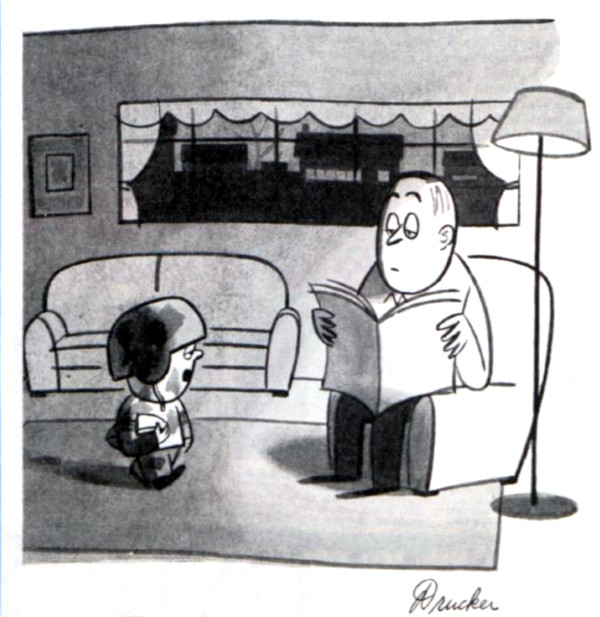

Cartoons: Gridiron Grins

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Blakley

November 18, 1950

Drucker

November 17, 1951

Drucker

November 17, 1951

Starke

October 6, 1951

John M. Price

October 6, 1951

Tom Henderson

September 30, 1950

Robt Day

November 25, 1950

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

6 Shocking Sports Retirements

Andrew Luck shocked the sports world on Saturday night when he suddenly retired as quarterback of the Indianapolis Colts. Though he had informed the NFL of his intentions and planned to hold a press conference on Sunday, word leaked out and hit social media even before the end of the Colts’ pre-season game against the Bears. Luck took to the press podium after the game to confirm the news and offer a version of the speech that he would have given the next day. It was a stunning moment, ranking with several other surprise retirements in sports history. We look back at six of the biggest, one for each (complete; 2017 doesn’t count) season that Luck played in the NFL.

Lou Gehrig

Lou Gehrig’s Retirement Speech (©MLB)

When “The Iron Horse” benched himself on May 2, 1939, after playing 2,130 consecutive games, fans knew that something was wrong with the Yankees slugger. He would never take the field as a player again, as in June he was diagnosed at the Mayo Clinic with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which kills the neurons that controls the muscles of the body. The diagnosis went public on June 19, 1939; the Yankees designated July 4 as Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day. At the ceremony, Gehrig delivered perhaps the most famous speech in the history of baseball, wherein he declared “Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” He was given a special rush election to the baseball Hall of Fame in December of 1940, and died at his home in the Bronx on June 2, 1941. Though ALS has afflicted other giants in their fields, like physicist Stephen Hawking, ALS is frequently and colloquially referred to as “Lou Gehrig’s Disease.”

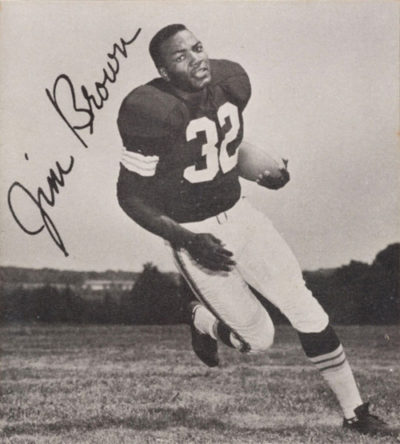

Jim Brown

Considered one of the most accomplished and dominant rushers of all time, Jim Brown would later parlay his no-nonsense, bone-crushing style of NFL play to a long-term career in film, notably featuring in action roles in The Dirty Dozen, Slaughter, and more. Brown was the first player to rush for more than 10,000 yards; he set both the single-season and all-time rushing records in his career. After nine years and still in prime shape, Brown abruptly retired from the game after Browns owner Art Modell threatened to fine him for every day he was absent from training camp due to production overruns. Brown decided to simply retire and focus on film and other endeavors, like social activism.

Magic Johnson

The Announcement: Magic Johnson (©NBA)

Earvin “Magic” Johnson was, quite simply, one of the greatest players to ever step foot on the basketball court. A fierce competitor and a passing genius, the wars between Magic’s Lakers and Larry Bird’s Celtics immediately became the stuff of legends. On November 7, 1991, Johnson brought almost the entire world to a halt when he announced that he had tested positive for HIV and would retire from basketball that day. Nevertheless, the fans loved Magic, and they voted him into the 1992 NBA All-Star Game; he scored 25 points and was named MVP. He was subsequently asked to join The Dream Team, the 1992 Olympic Men’s Basketball team; along with Bird, Michael Jordan, and a roster of legends, Magic brought home the gold medal. Johnson’s attitude had changed by 1994, and he returned to the league for two more years, as well as a brief stint in Europe in 1999. Johnson proved that HIV did not equate to the death sentence that it was perceived as at the time, and continues to thrive today as a business figure and activist.

Michael Jordan

As the most popular basketball player on Earth, Michael Jordan had excelled as an All-American in high school and an NCAA champion at North Carolina before setting the world on fire with the Chicago Bulls. In 1993, Jordan led his team to their consecutive championship, a vaunted “three-peat.” Unfortunately, His Airness didn’t get to enjoy that feat for long; his father was murdered by carjackers in August of that year. In October, Jordan announced his shocking retirement from basketball while expressing a desire to play professional baseball (something that his father had always wanted him to do). Jordan signed a contract with the Chicago White Sox and entered their minor league system. He played in 1994 and 1995; however, the 1995 MLB strike led to his decision to return to the court. Though the Bulls were ushered out of the playoffs by Orlando, despite Jordan’s return, they had the last laugh as the reinvigorated squad went on to put together a second “three-peat.” Jordan announced his retirement again in 2001, recanted, and played until 2003.

Barry Sanders

One of the great running backs in football, Barry Sanders of the Detroit Lions led the NFL in rushing four times in the 1990s. He was even named the league’s MVP in 1997, when he posted a gaudy 2,053 rushing yards. Sanders was beloved for his trademark elusive running style, filled with an almost balletic footwork and tremendous ability to shake defenders; that showmanship stood in contrast to his generally humble attitude, as he wasn’t given to attention-getting on-field celebrations. His sudden retirement functioned in much the same way, as he first announced it with a fax to The Wichita Eagle, his hometown newspaper. Although he’d played 10 years, observers noted that he could have still had many more productive years on the field. Sanders later went on the record in the book Barry Sanders: Now You See Him…His Story in His Own Words that the major element in his retirement was frustration that the Lions organization was not committed to building a winning team around him. In that atmosphere, Sanders decided to walk away from the game.

Pat Tillman

In the shadow of 9/11, many young Americans felt compelled to join the military. So did Pat Tillman, the safety for the Arizona Cardinals. After completing his contract in 2002, Tillman and his brother Kevin (who had signed to play baseball with the Cleveland Indians) joined the Army. The idea that Pat Tillman turned down a new multi-million-dollar contract to joined the armed forces came as a surprise, but he was lauded as an American hero for putting his feelings of duty above celebrity and money. Both Tillman brothers finished Ranger Indoctrination Training and were assigned to the 2nd Ranger Battalion. After serving in the opening stages of the invasion of Iraq, the Tillmans finished Ranger School in Fort Benning, Georgia. He was given the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the 2003 ESPYs. Pat Tillman was deployed to Afghanistan; unfortunately, on April 22, 2004, Tillman was killed in a friendly-fire incident, an event that sparked numerous investigations and Congressional inquiries. In 2008, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform reported that, “It is clear, however, that the Defense Department did not meet its most basic obligations in sharing accurate information with the families and with the American public.” Today, Tillman’s legacy serves as an example of a person that’s willing to do the hard thing because they believe it is right, rather than do the easier thing in comfort.

Featured image: Jamie Lamor Thompson / Shutterstock.com.

30 Years Ago: Nolan Ryan Threw His 5000th K

He never threw a perfect game. He never won the Cy Young Award. But he dominated baseball across an improbable four decades. He was an eight-time All-Star. He remains the all-time leader in no-hitters. And he is the only player to hurl more than 5,000 strikeouts. He broke that seemingly impossible line 30 years ago this week as a member of the Texas Rangers, and he would continue to add to that gaudy total for four more years. The man in question is, of course, the legendary Nolan Ryan.

Born in 1947, Ryan took up the game at a young age and excelled in high school. He was first scouted by the Mets during a 1963 game. After graduation in 1965, the Mets took Ryan in the 12th round of the MLB draft. From 1965 through 1967, Ryan pitched for the minor league organizations of the Mets, making some Major League appearances in 1966 during late-season roster expansion. He was out for much of 1967 for a combination of Army Reserve service and illness. During his tenure in the minors, as he worked on his control, he posted more than 450 strikeouts.

By 1968, Ryan was firmly ensconced in the majors. He was part of the 1969 “Miracle Mets,” a New York line-up that reversed years of Mets frustration; since its inception in 1962, the team hadn’t had a single winning season. Thanks in large part to a murderer’s row of pitchers that included Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Gary Gentry, Ron Taylor, Tug McGraw, and Ryan, the ’69 team overtook the Cubs as they made their way to 100 wins. Ryan played pivotal roles in two “Game 3” appearances in the post-season. In Game 3 of the National League Championship Series against the Braves, he came on for seven relief innings and his first playoff win; he then saved Game 3 of the World Series in relief, shutting out the Orioles for 2-1/3 innings. The Mets went on to win the World Series.

However, Ryan’s tenure in New York wouldn’t last forever. After being traded to the Angels, Ryan finally got to be a starter. He responded by throwing 329 strikeouts in 1972, which was the fourth-highest total of the century at that point. This set the tone for Ryan’s career; while he was extremely prone to walking (or, on occasion, hitting) batters, his blistering speed and propensity for dominating performances made him a star. He went to the Houston Astros as a free agent in 1980, becoming the first player to earn a million dollars per season. In April of 1983, Ryan broke the all-time strikeout record by retiring his 3,509th batter; just over two years later, he recorded his 4,000th K.

Ryan signed with the Texas Rangers for 1989; he was 42. The seemingly impossible plateau of 5,000 strikeouts was in sight. On August 22, at the top of the 5th in a game with the Oakland Athletics, Ryan faced off against future Hall of Famer Ricky Henderson, whom he’d already struck out previously in the evening (he was 4,998, to be exact). Ryan retired Henderson on a blazing fastball. As the crowd went crazy, Ryan simply doffed his cap, shook hands with some teammates, and went back to work.

Nolan Ryan throws strikeout 5,000. (©MLB)

Over the next four years, Ryan just kept on going. He announced his retirement before the beginning of the 1993 season. Unfortunately, he didn’t get to finish as, two starts short of his expected end date, he tore a ligament in his throwing arm. He was still, at the age of 46, throwing around 98 mph. Upon his retirement, Ryan had set a Major League record for seasons played (27); he was, at the time, also the only remaining player to have made the big leagues in the 1960s.

The numbers for Ryan’s career remain extraordinary. He finished with 5,714 strikeouts; having pitched 5,386 career innings, which means he averaged 1.06 Ks per inning over the course of his entire career. He did, however, give up 2,795 walks, though his career ERA (Earned Run Average) was a rock-solid 3.19. Ryan’s career Win-Loss record was 324-292. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1999, his first year of eligibility, with a landslide vote (491-6). Ryan’s number was retired by the Angels, the Astros, and the Rangers, making him one of only a handful of players to have their number retired by more than one team. In his post-playing career, Ryan has become the owner of two minor league teams, served as Texas Rangers president and CEO from 2008 to 2013, and currently acts as executive adviser to Jim Crane, owner of the Astros. Ryan’s son Reid, one of the Hall of Famer’s three children with his wife, Ruth, is the Astros’ president of business operations.

They say that no record is permanent, but Ryan’s crowning achievement might well be untouchable. Number two on the all-time strikeout list, Randy Johnson, retired at 839 pitches behind Ryan. You have to go all the way down to slots 17 and 18 to find the only active players on the list; at this writing, CC Sabathia has 3,068 (and will retire this year after 18 years), and Justin Verlander has 2,934 after 14 years. A Houston Astro, Verlander is currently averaging more strikeouts than innings pitched in his career. Sound familiar? If he continues at his current rate, Verlander might be able to eclipse Ryan . . . in 10 more years. While we wait to see if that mountain can be climbed, we can still sit back in awe and appreciate of one of the greatest to ever play the game.

Featured Image: Nolan Ryan – Tiger Stadium, 1990. (Photo by Chuck Andersen; Wikimedia Commons via Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

The 7 Most Controversial Sports Moves

More than sixty years ago, the Dodgers made a move that’s still hotly debated. It wasn’t about management or personnel; it was about the location of the team itself. Forsaking Brooklyn for Los Angeles, the Dodgers earned New York’s eternal enmity in 1957 (and were followed by another New York team, the Giants, the following year). Team moves happen for a number of reasons (mostly money), but some have a harsher effect on the locals than others. Here are seven of the most controversial team moves in sports.

1. 1945: What Do You Mean the Rams Are from Cleveland?

The Rams franchise was established in Cleveland in 1936; initially, they were part of the American Football League. The following year, they switched to the competing National Football League, and remained until 1945, when they won the League championship. In 1946, the team moved to Los Angeles, based in part on poor attendance. Even the championship game couldn’t fill more than half the seats. Their departure didn’t leave Cleveland teamless; that same year, they got the Browns (named after Ohio State coach Paul Brown).

Upon moving to L.A., the Rams integrated African-American players as a condition of being able to use the Coliseum. With the Browns also choosing the take African-American players, the Rams helped open the League to a whole new segment of athletes and fans. The move also helped establish pro sports in L.A. and set the tone for many future teams to go west.

2. 1957: The Dodgers Move to L.A.

The Dodgers had been in Brooklyn since 1884, breaking the color barrier along the way when Jackie Robinson joined the club in 1947. After a number of rough years, they made it to the World Series in 1956, only to lose to the Yankees. The Dodgers’ majority owner, Walter O’Malley had encountered a number of obstacles acquiring land around New York for a new stadium, and the city of Los Angeles was simultaneously trying to entice teams to come west. After striking a deal with the city that allowed the franchise to build where they wanted, and to also own the stadium (rather than split it with the city), the Dodgers decided to move. One last roadblock came from the National League itself, which told the team they’d block the move unless another team went west. The Giants had been having their own stadium troubles, and it wasn’t long before both teams split for California. The double departure paved the way for the foundation of the Mets in 1962.

In a 2010 interview with WNYC, Michael Shapiro, author of The Last Good Season: Brooklyn, the Dodgers, and Their Final Pennant Race Together, summed up the impact of the move on the city: “What I came to understand is that what the Dodgers were about was a topic of conversation. That, in many ways, is what really makes cities work and what holds cities together . . .I think you can make a really powerful argument that what Brooklyn lost after the Dodgers left was a topic of conversation.”

3. 1960: Alliteration is More Important Than the Number of Lakes

The Lakers actually started with a move when Ben Berger and Morris Chalfen bought the Detroit Gems in 1947 and brought the team to Minneapolis. After a losing season that included the team surviving their plane crash-landing during a snowstorm, then-owner Bob Short decided to move the team to Los Angeles. They became the NBA’s first west coast team; in that inaugural year, star Elgin Baylor and rookie Jerry West led the team back to the playoffs, though they missed the finals by a basket. One interesting wrinkle about the move is that while the name “Lakers” was completely attributed to Minnesota’s 12,000 lakes, the name was preserved in the move, partially because of the nice alliteration.

4. 1982: The Raiders Begin Their Travels

The Oakland Raiders debuted in 1960 as one of the founding teams of the American Football League (which later merged with the NFL in 1970). In 1982, the Raiders moved to L.A., a change that lasted 12 years. At the outset of the 1995 season, they shifted back to Oakland, partially enticed by the city spending $220 million on stadium renovations. In 2016, billionaire casino magnate Sheldon Adelson put together a proposal for a new domed stadium in Las Vegas that would house both the UNLV team and a potential NFL franchise. Adelson held discussions with Raiders owner Mark Davis, who offered to contribute $500 million to the construction of the stadium if Las Vegas would also contribute. When Nevada legislators came through with $750 million in funding, Davis announced his declaration to move, a motion that was approved by the NFL. The Las Vegas Raiders are scheduled to kick off in 2020.

5. 1984: The Colts Sneak Out

After a lengthy and complicated run of cities, team names, and organization changes that stretched from Dayton, Ohio in 1920 through Brooklyn, Miami, Boston, and Dallas, the franchise officially became the Baltimore Colts in 1953. Over the years, conditions at Memorial Stadium continued to deteriorate, with seating, office space, and other amenities being inadequate for the needs of both the Colts and the Orioles baseball team, which shared the stadium. After years of struggle and attempts to get stadium improvements and funds, the city essentially said that they wouldn’t put in the improvements unless the Colts and Orioles signed long-term leases. The Orioles signed for one year; the Colts didn’t sign at all. The city of Indianapolis had begun construction of the Hoosier Dome, hoping to lure a team to the city; when they pitched Colts owner Robert Irsay, it had the desired effect. As the Maryland legislature attempted to pass a bill to seize the organization, Mayflower moving trucks rolled up to the Colts complex and moved the team equipment and belongings out. By the time that the legislature passed the eminent domain bill to seize the team, the Colts had made their way to Indianapolis. They became the Indianapolis Colts with the onset of the 1984 season, earning the enmity of Baltimore forever; however, they did endorse Baltimore receiving a franchise in the ‘90s, which eventually became the Ravens.

For some former Baltimore Colts, the move came as a savage betrayal. Legendary Colts quarterback and Hall of Famer Johnny Unitas severed all of his ties with the Colts organization after the move. He later threw his support behind the Ravens, recognizing them as the true legacy team. Today, a statue of Unitas stands outside M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore, a defiant reminder that some team moves are felt deeply by former players.

6. 2012: The Nets Get Out of New Jersey While They’re Young

The Nets began life as a charter team of the ABA, a presumptive rival to the NBA that debuted in 1967. In their first season, they were the New Jersey Americans. The next year, they moved to Long Island and became the New York Nets; they would win two ABA championships under that name. In 1976, the ABA collapsed and four teams merged with the NBA, including the Nets. They went back to the New Jersey in 1977 and became, of course, the New Jersey Nets. That lasted until 2012. As early as 2005, the Nets had announced their intention to move to Brooklyn, but financing, partnership agreements, and lawsuits among various parties spaced out both the move and the building of their eventual home, the Barclays Center. However, all the obstacles were cleared by 2012, and the Nets, like everyone else, moved to Brooklyn.

7. 2014: Ending 12 Years of Hornet/Bobcat/Pelican Drama

Sometimes, you have a fairly straight team move. Other times, you have a very confusing series of circumstances. The Charlotte Hornets debuted in the NBA in 1988 as an expansion team; that lasted until 2002, when the team moved to New Orleans and became the New Orleans Hornets. In 2004, the NBA placed a new expansion team in Charlotte, which became the Charlotte Bobcats.

An unintended side effect of the Hornets’ residency in their new city came in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when the storm seriously damaged New Orleans Arena. The team was forced to play in Oklahoma City’s Ford Center for the rest of that season and the next season before they could return home. However, their success in OCK allowed the Seattle SuperSonics to successfully move and become the Oklahoma City Thunder.

By 2013, the Hornets decided that they wanted to rebrand and give themselves a name more closely associated with NOLA. Ultimately, they decided that they would become the New Orleans Pelicans. The following year, the Bobcats took back the now-vacant Hornets to become the Charlotte Hornets once again. Today, the Pelicans, Hornets, and Thunder continue to be active, with the Thunder serving as a perennial playoff contender.

Questions remains if the NBA will return to Seattle. Though the Jet City did recently get the franchise for a new NHL team, NBA commissioner Adam Silver says that while he loves Seattle, getting the city another team isn’t a high priority for the league at the moment. Then again, from what we’ve seen, team moves will always be a possibility.

Featured image: The RCA Dome (originally the Hoosier Dome) was built to lure teams to Indianapolis; it was demolished in 2008 and replaced by Lucas Oil Stadium. (Josh Hallett, Wikimedia Commons via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.).

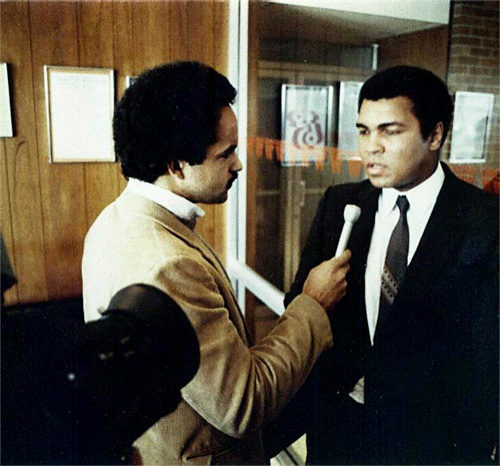

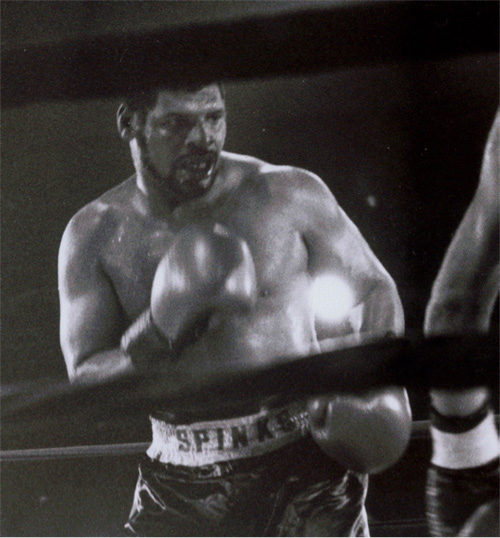

40 Years Ago: The Greatest Wins One More Time

Leon Spinks stunned the world on February 15, 1978. The 1976 Olympic Gold medalist for Boxing, Spinks got the opportunity to face “The Greatest,” Muhammad Ali. Ali had just come off of a widely praised victory over Earnie Shavers, and chose Spinks as his opponent partially due to a desire to avoid Ken Norton, whom he’d already fought three times. Spinks amazed everyone by beating Ali in a split decision in only his eighth professional fight.

A number of factors led to Ali’s loss. He had already flirted with retirement in 1976 before returning the next year to beat Alfredo Evangelista. He was out of shape. And he underestimated his opponent. He wouldn’t make that mistake again. Ali got his chance for some payback when Spinks agreed to a rematch for the World Boxing Association heavyweight title in New Orleans on September 15, 1978.

Despite the fact that he’d lost in February, Ali was still considered the favorite. The wildly charismatic and controversial boxer had managed to delight and infuriate the American public throughout his career. When The Saturday Evening Post profiled him in 1964, one significant focus of the piece had been his conversion to Islam. At time of the Spinks fights, Ali had recently undergone an additional religious journey, turning from the Nation of Islam in 1975 and embracing Sunni Islam beliefs.

On the night of September 15, it was safe to say that the world was watching. ABC had the rights to the fight, and they broadcast it to an estimated 90 million people in the U.S. Around the world, the total audience for the bout was a record 2 billion people. Ali arrived in shape and ready to throw hands. Spinks found himself fighting a different Ali. The man he’d fought in February had been a bit sluggish; this Ali focused on footwork and jabs, locking up Spinks up whenever he came in too close (in fact, the referee stripped the fifth round from Ali in favor of Spinks because of Ali’s excessive holding).

The fight went the distance, and Ali won in a unanimous decision by the judges. It was his third WBA heavyweight championship, making him the first man to accomplish that feat. Ali sent an official letter to the WBA in June of 1979 to announce his retirement, but he ended up competing in two more fights. He would lose once to Larry Holmes in 1980, and again to Trevor Berbick in 1981. After that, he hung up his gloves for good. After Ali, only one other American boxer has had three WBA heavyweight reigns, fellow Olympian Evander Holyfield.

Spinks didn’t have a stellar career after the fight with Ali. He himself was beaten by Holmes in 1981, though Holmes would later drop the title to Leon’s brother, Michael Spinks, in 1985, making them the only brothers to be heavyweight champs. Leon Spinks tried to shed weight and box as a cruiserweight to little success. After that, he became a professional wrestler for Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling in Japan; he took that the title in 1992, making him the only person to be both an American boxing and professional wrestling champion in his career. Leon and Michael Spinks, like Ali, have been inducted into the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame. Leon’s son, Cory, was also a boxing champ in the welterweight and IBC junior middleweight divisions. Today, Leon Spinks lives in Las Vegas, Nevada.

As for Ali, his later years focused on humanitarian projects and philanthropy. Though he began to suffer from the effects of Parkinson’s Disease, he kept a high public profile. A Gold medal-winning Olympic boxer himself (he earned the Light Heavyweight medal in Rome in 1960), he was invited to light the Olympic flame at the Atlanta games in 1996. After years of declining health, Muhammad Ali died on June 3, 2016 at age 74, leaving behind the vibrant legacy of a larger-than-life personality that couldn’t help but set new standards in his sport.