Is Your Child’s School Being Unfairly Penalized?

No moral intuition is more hardwired into Americans’ conception of economic justice than equality of opportunity. While some of us may be rich and others poor, we are willing to accept such outcomes as long as everyone has an equal shot at success. The moral legitimacy of the market’s distribution of income rests on a presumption that our system rewards ingenuity, hard work, talent, and risk-taking rather than race, class, family connections, or some other advantage we consider unearned, illegitimate, or unfair.

“In every wise struggle for human betterment, one of the main objects, and often the only object, has been to achieve in large measure equality of opportunity,” declared President Theodore Roosevelt in a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, in 1910, laying out the “square deal” he believed was due to all Americans.

In a speech later that year, Roosevelt took pains to reassure members of the New Haven Chamber of Commerce that his notion of equal opportunity fit squarely within the context of a market economy. “I know perfectly well that men in a race run at unequal rates of speed. I don’t want the prize to go to the man who is not fast enough to win it on his merits, but I want them to start fair.”

For the first time in American history, the steady march toward greater equality of opportunity seems to be headed in the opposite direction.

Equality of opportunity, of course, taps into the conception Americans have of themselves as a people who fought one war to shake off the tyranny of a British monarchy and aristocracy and another to shake off the chains of slavery, a people who welcomed wave after wave of ambitious immigrants yearning for a better life. Yet there is now a sizable and growing body of evidence that, despite elimination of most legal barriers to equality of opportunity, the luck of which parents you were born to continues to play an outsized role in determining economic success. Whether it’s by way of the genes we inherit (nature) or the circumstances in which we are raised (nurture), the results of this parental lottery are more important than ever in determining our natural capabilities and the degree to which we are able to develop those capabilities and bring them to an increasingly competitive marketplace. Indeed, for the first time in American history, the steady march toward greater equality of opportunity seems to be headed in the opposite direction.

Our education system is no longer serving its historical role of equalizing economic opportunity and increasing social mobility. Rather, it has become an instrument by which children lucky enough to be born into favorable circumstances increase their economic advantage over those who were not.

It was 65 years ago that the Supreme Court, relying largely on evidence and expert opinion from social scientists, ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that sending black children to separate schools was inherently unequal. Now it is time to extend that constitutional principle and declare that it is no longer acceptable to organize and finance public education in a way that segregates poor children in separate schools.

Because of our reliance on local property taxes to fund public schools, and public school systems that organize schools around residential neighborhoods, we have a system that in many places provides less funding, less effective teachers, and worse facilities to poor students who require more resources and better teachers to reach comparable educational goals. Moreover, there is clear evidence from social science research that segregating poor children in the same schools deepens their disadvantage. The only practical way to end this class segregation in education is the same way racial segregation was ended — with a Supreme Court finding that segregating poor students in the same schools denies them the equal protection of the law guaranteed by the Constitution.

As it happens, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected that view in 1973 in a case that few remember today, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez. In a 5–4 ruling, the Court — which only two decades before, in Brown, had recognized the importance of public education to a democratic society and a child’s success in later life — reversed course and declared that public education was not a fundamental right under the Constitution. It also found that discrimination on the basis of class did not warrant the same strict scrutiny as discrimination on the basis of race. Writing for the majority, Justice Lewis Powell worried that if public education were to be treated as a fundamental right, the Court would find itself on a slippery slope that would also require it to give similar status to housing and medical care.

It is time to revisit those issues. One reason is new evidence from social science studies showing that the socioeconomic characteristics of a child’s classmates are a better predictor of educational achievement than a child’s own socioeconomic background. Another is the change in case law. In the intervening years, there has been a long line of Court decisions striking down affirmative action plans at universities or guaranteeing parents control over their children’s schooling, in which the Court’s conservative majority recognized something that sounds very much like a constitutional right to education. With a series of education reform bills, Congress has also established a strong federal interest in ensuring that all students attain minimal levels of educational achievement, with a particular emphasis on low-performing students and school districts. All of these developments provide a solid legal basis to ask the Court to reconsider the issue and declare that Rodriguez was wrongly decided.

There is nothing sacred about the idea that municipalities and school districts have to have the same boundaries, or that public education needs to be funded primarily through property taxes. To assure equal access to an adequate education, the federal courts could require states to redraw school district boundaries in ways that would end desegregation by class and put rich and poor students in the same school systems. Courts could order states to devise statewide funding formulas that would begin to break the pernicious link between local property values, per-pupil spending, and educational achievement. And judges could even insist that the newly redrawn school districts rely on student choice for school assignments and make extensive use of magnet schools.

I don’t underestimate the political and legal difficulties in bringing about such a radical restructuring of public education. I am old enough to remember the bruising battles over busing, and I am aware that the process of bringing racial integration to public schools has hardly been a smashing success. Class integration would be no less challenging, but it is also no less of a moral imperative.

It is worth recalling that the campaign to overturn the separate but equal doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson energized a generation of Americans in the 1960s. Overturning Rodriguez and establishing the fundamental right of all children to a decent education could be the legal issue that energizes a new generation eager to ensure that history continues to bend toward justice. It will take patience, persistence, and political courage, but this is the kind of defining moral issue that is worth the effort.

From Can American Capitalism Survive? by Steven Pearlstein, copyright © 2018 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Tax that Criminalized Marijuana

The history of cannabis in America goes all the way back to Jamestown. The country’s first settlement grew the plant for hemp needed to make ropes. Cannabis continued to be grown in the 400 years since, though its purpose shifted over time.

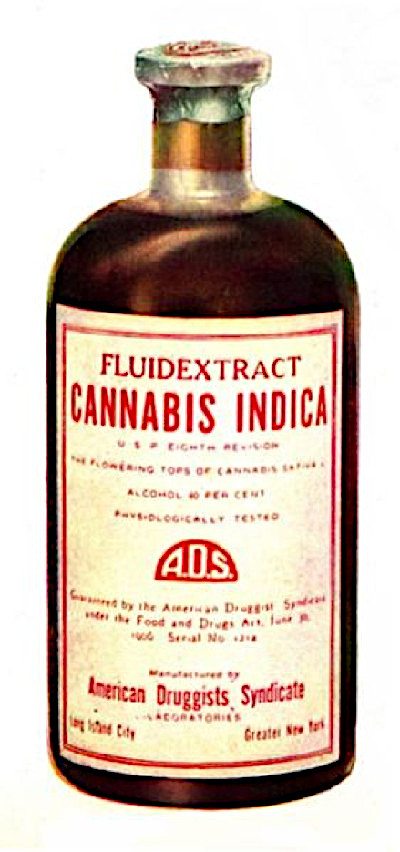

Before 1937, cannabis and its products (marijuana being one) were perfectly legal. In fact, the drug was not yet used recreationally, but was commonly used in medicines in the early days of pharmacy, though not always included on the label. This all changed at the turn of the 20th century.

Americans began discussing what had previously been viewed as a useful crop as a harmful substance. The association of marijuana used recreationally with the influx of Mexican immigrants during the Mexican Revolution and Great Depression encouraged public sentiment against “marihuana,” as it was spelled back then. A September 28, 1935, article in The Saturday Evening Post raised concerns about marijuana’s dangerous influence in the wake of Prohibition repeal:

There are many states in which the police have no authority whatever to arrest either an addict or a peddler; that must be done by the comparatively small force of Federal men. There are likewise states which have no protection whatever against the rapidly growing sale and use of cannabis sativa, commonly known as marijuana, or hashish, and which grows as a weed in every part of America, particularly in the West.

Pretty Boy Floyd was alleged to have been crazed on marijuana when he aided in what now is known as the Kansas City Massacre. Give a Mexican smuggler enough of it and he will wade the Rio Grande, shooting as he comes, and caring nothing for the fact that he may be outnumbered four to one by border patrolmen. The gangster killer of today rarely takes a shot of cocaine to strengthen his nerves, but smokes a few marijuana cigarettes instead; they have greater effect.

By 1945 this magazine described marijuana as a “menace to the public welfare” in “Sleeping Pills Aren’t Candy” on February 24.

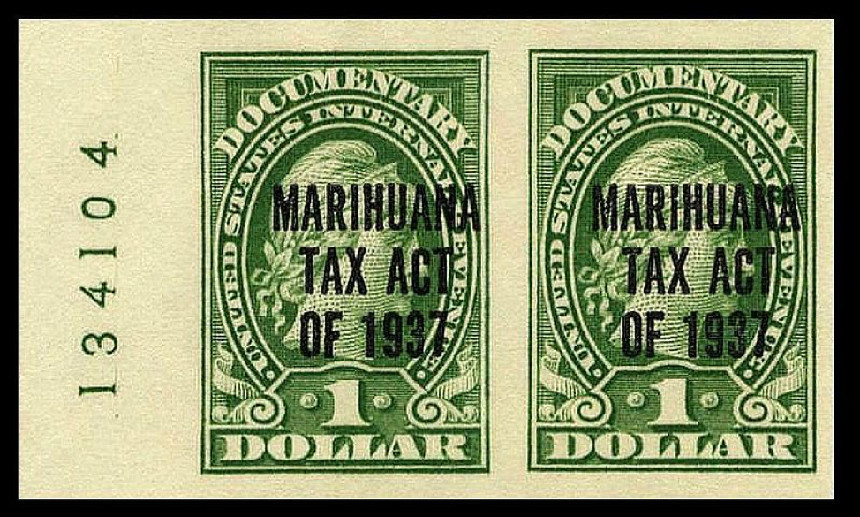

In April of 1937, congressmen Harry Anslinger proposed The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. This act would require marijuana users, growers, distributors, or anyone planning “to acquire or otherwise obtain any marihuana,” to purchase a tax stamp. The drug had been a staple in medicines at the time and had not been limited by any federal regulations before 1937 (although 29 states had outlawed its use by 1931). The original act states that “Any person subject to the tax imposed by this section shall, upon payment of such tax, register his name or style and his place or places of business with the collector of the district in which such place or places of business are located.” Essentially anyone wishing to purchase a marihuana tax stamp would have to submit all of their personal information for government records.

The law taxed marijuana at around $1 per ounce, or $17.95 today. The price, in addition to the forced self-reporting of anyone with a connection to the drug, discouraged its sale and use. The law was enacted on August 2, 1937, marking the day when unstamped cannabis became illegal in the United States.

The Tax Act led to the arrest of two men on its very first day, resulting in the first imprisonments due to possession and sale of marijuana. The law dictated that guilty individuals “shall be fined not more than $2,000 or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.” Samuel Caldwell was fined $1,000 and given four years’ hard labor for dealing. His client, Moses Baca, was sentenced to 18 months in prison.

The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 were ruled unconstitutional in 1969 after the Supreme Court found it in violation of citizens’ Fifth Amendment rights. Requiring all marijuana users to identify themselves, the amount of weed they had, and where they got it from amounted to self-incrimination. The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (under which the Controlled Substances Act was passed) was put into action soon afterward, ensuring marijuana remained illegal and ushering in the beginning of the war on drugs.

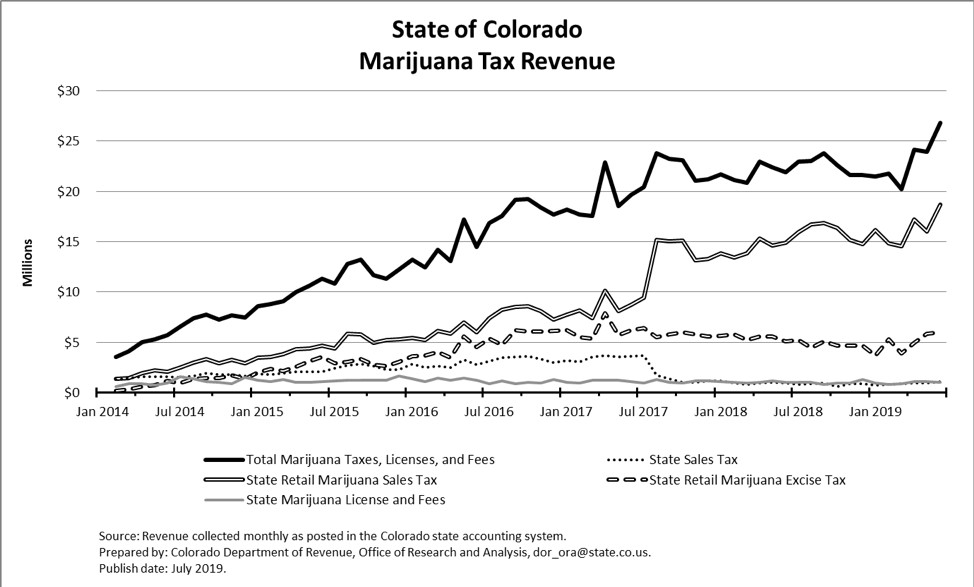

The modern debate on the evils of marijuana seems to have turned. Today, 29 states have legalized medical marijuana and 11 have legalized weed for recreational use. Each of those states has their own laws and regulations surrounding the drug, including modern taxes.

Modern marijuana taxes to not act as a registry for all drug users but do create profit for states’ governments. The taxes obtained from weed in states that have legalized recreational marijuana rival those states’ taxes on alcohol sales. In Colorado in 2018, where recreational marijuana is legal, an ounce of weed costs $199.89. This price does not include the 2.9 percent sales tax, 10 percent special marijuana tax, or the 1 percent local tax that would add $27.79 to the price (not too far from 1937’s $17.95). Colorado generated $266,529,637 in revenue from marijuana taxes in 2018 alone.

The Tax Act of 1935 did not explicitly make weed illegal, but it did give cause to arrest anyone without proper registration. This act began a spiral of legislation that did criminalize the drug (in addition to many others) and resulted in many people’s imprisonment. Taxes on marijuana today are not intended for incrimination, as individual users do not have to self-identify, and the stigma surrounding the drug has lessened in the 82 years since the tax act was passed. While federal legislation still condemns the drug as illegal, today marijuana can be purchased legally in many states — no stamp required.

Featured image: The 1937 marihuana review tax stamp (Wikimedia Commons, Department Internal Revenue; Smithsonian National Postal Museum)

Considering History: How Whiskey and Taxes Helped Create the United States

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The April 15 deadline for Americans to file their taxes has arrived, reminding us that controversies over taxes are among the oldest and most defining U.S. social conflicts. Indeed, the multi-year battle over President George Washington’s “whiskey tax” was the first substantive post-Constitution domestic conflict and helped establish the United States in a number of significant ways.

Earning revenue was one of the newly created federal government’s highest priorities. The American Revolution had been a costly affair, and under the 1780s Articles of Confederation, the weak central government did not have the authority to collect taxes; that government had thus accumulated more than $50 million in debt by 1789 (with the states accruing another $25 million or so). President Washington assigned his friend and Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, the task of addressing that sizeable debt crisis; Hamilton first convinced Congress to consolidate federal and state debt with his 1790 Report on Public Credit, and then set about establishing new mechanisms for increasing federal revenue.

Hamilton settled on the creation of the new nation’s first domestic tax, an excise tax on distilled spirits. As whiskey was the most popular such domestic spirit, when Congress passed Hamilton’s proposed bill in March 1791, the law became known as the “Whiskey Act,” and the tax as the whiskey tax. Along with his financial allies and the President, Hamilton also had the support of early temperance reformers, who saw the excise as a “sin tax” that could curb excess drinking. But the tax was controversial, not only in the House of Representatives (where 21 of the original 56 Congressmen voted against it) but also and especially in those regions that distilled the most whiskey.

Western Pennsylvania was one of the principal such regions, and reacted with especial hostility to the whiskey tax. The area was part of the frontier of the United States in the period, and as is often the case with frontiers, was populated by communities with both less wealth and more of an independent streak than many of their fellow Americans. The region’s whiskey distillers apparently saw the tax not only as a significant financial imposition, but as an attempt to privilege larger, more incorporated eastern distillers at the expense of these independent, local businesses. The Whiskey Act also required that all stills register with the federal government or appear in federal court, which was located in Philadelphia hundreds of miles away. For all these reasons, the Western Pennsylvania distillers perceived the tax as federal overreach and invasion, and mounted a campaign of armed resistance that came to be known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

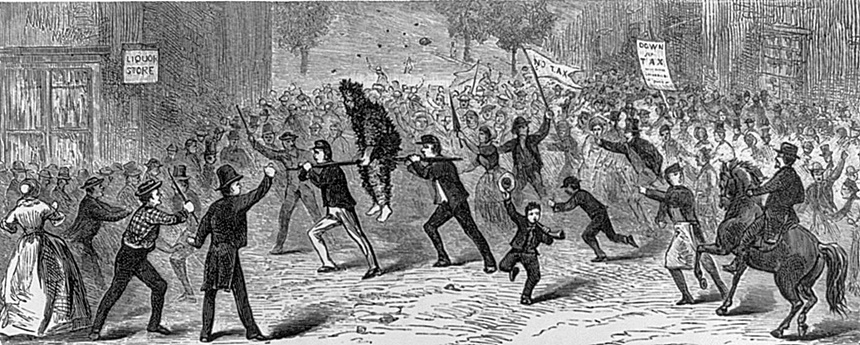

Beginning in September 1791, the rebels took numerous violent actions against tax collectors and other federal representatives. Collector Robert Johnson was tarred and feathered in Washington County on September 11, 1791, and the federal agent sent to serve warrants to Johnson’s attackers was similarly tarred and feathered. The resistance grew throughout the next two years, including both further acts of violence and an organized convention in Pittsburgh in August 1792. But it was in the summer of 1794 that the rebellion truly exploded in full armed conflict, including the July 1794 Battle of Bower Hill with federal marshals and the August 1794 march of more than 7,000 rebels (many of whom apparently did not own whiskey stills but saw the movement as an expression of broader grievances with the government) on Pittsburgh.

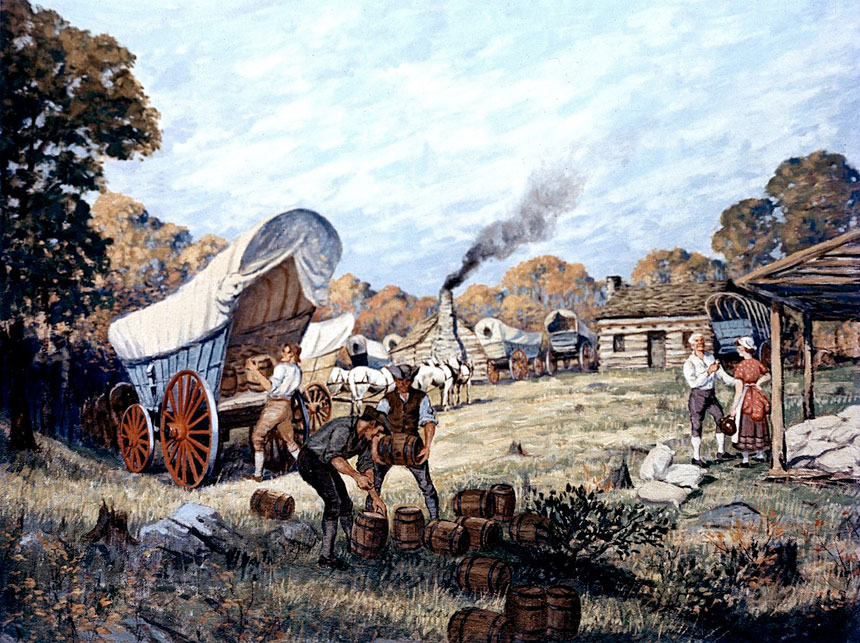

Faced with this growing rebellion, President Washington could no longer continue simply to send tax collectors and federal agents. After extended consultation with his cabinet, Washington took two complementary actions: in early August he sent three prominent Pennsylvanians (U.S. Attorney General William Bradford, Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Jasper Yeates, and U.S. Senator James Ross) as peace commissioners to negotiate with a committee of rebel leaders; and in late September he organized a federalized militia (under the authorization of the 1792 Militia Act) of more than 12,000 troops from Pennsylvania and three other Mid-Atlantic states (New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia), at the head of which Washington himself marched gradually west from Philadelphia (then the U.S. capital) in a show of striking national force (marking the only time a sitting president has led troops in the field).

These combined actions achieved their desired effect, and the rebels dispersed without a shot being fired by Washington’s militia. Only two of the rebel leaders (John Mitchell and Philip Weigel) were convicted of treason, and both were subsequently pardoned by Washington (apparently against Alexander Hamilton’s wishes). Yet those somewhat anti-climactic final acts did not mean that the Whiskey Rebellion’s drama had not been an influential one. Indeed, both the taxation itself and (especially) the multiple layers of the Washington administration’s response to the rebellion helped make clear that the Constitution had in fact created the strong, centralized federal government for which its supporters had argued. This government could and would both levy domestic taxes and counter organized and even armed resistance of its citizens to such policies.

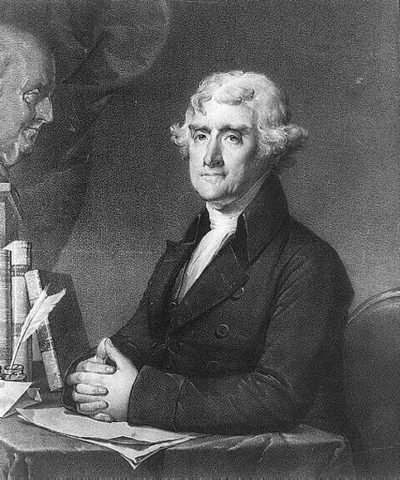

Yet at the same time, the Whiskey Rebellion’s opposition would also prove influential, and not only to future generations of tax resisters and critics. While political parties were already beginning to develop in these earliest years of the Republic, the nascent Republican Party grew significantly in response to and in support of the Whiskey Rebellion and its local and agrarian critiques of the whiskey tax and the federal government. When Thomas Jefferson won the presidency as the Republican candidate in the highly contested election of 1800, one of his early actions as president was to usher through a repeal of the whiskey tax and all internal taxes. The battle over taxation has been a political and social as well as a policy conflict since our founding moments, and seems likely to remain so throughout our American future.

Featured image: George Washington leading his troops (Attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer, Metropolitan Museum of Art)