Here He Comes to Save the Day: Mighty Mouse’s TV Debut

He originally hit the big screen as Super Mouse in 1942, even sporting the familiar red and blue of the character that he parodied. But by 1944, he’d picked up a new name and, later that year, a new yellow and red suit. You know him today as Mighty Mouse, he of the outsized super-powers and infectious theme song. But as popular as he was in the 77 theatrical shorts that ran between 1942 and 1954, that would pale in comparison to his reach upon his move to TV in 1955.

Mighty Mouse started animated life with a Superman parody concept from animator Isidore Klein at the Terrytoons studio. Klein suggested poking fun at the Man of Steel, but originally drew the character as a fly. Studio owner Paul Terry saw the value in the idea, but, possibly keying in on another animated icon, had the character rendered as a mouse instead. Super Mouse debuted in the 1942 theatrical short, “Mouse of Tomorrow.” The title was a play on The Man of Tomorrow, one of Superman’s many nicknames. A familiar trope of the character emerges in the first short, which features him rescuing endangered mice from scary, even fascistic, cats. As the studio cranked out more cartoons against the backdrop of World War II, the parallels between the animated cats and Nazis would get much more explicit.

The first “Super Mouse” cartoon, “Mouse of Tomorrow.” (Uploaded to YouTube by TerryToons; Public Domain)

In “The Wreck of the Hesperus,” the eighth short, the Mighty Mouse name is used for the first time. It’s clear by the eleventh installment that the studio was ready to move away from the parody costume, as they switched him to a red costume with a yellow cape. By “The Sultan’s Birthday,” the mouse’s fifteenth adventure, his look has settled into the familiar yellow and red. While Mighty Mouse continued to appear regularly on the big screen and was one of Terrytoons’s biggest characters, he wasn’t as popular as, say, Tom & Jerry, Woody Woodpecker, or other regular inhabitants of the shorts. By 1955, Terry licensed all of his Terrytoons cartoons to CBS, eventually completing a sale of the studio to the network by the following year. On December 10, 1955, Mighty Mouse became a TV star.

The first series was called Mighty Mouse Playhouse, and featured the classic shorts repackaged for TV. Mighty Mouse caught on in a big way with the public, and the show ran for just short of 12 years. The theme song by Marshall Barer, with its call of “Here I come to save the day!” became as familiar as any tune in pop culture. CBS did make three more theatrical shorts between 1959 and 1961, bringing the total to 80, but abandoned the practice with December 1961’s “Cat Alarm.”

When Playhouse ended in 1967, the character stayed alive in comic books and TV syndication packages. Mighty Mouse returned to CBS in 1979, along with fellow Terrytoon characters Heckle & Jeckle, in the aptly named The New Adventures of Mighty Mouse and Heckle & Jeckle. The hour-long show included new cartoons for both sets of characters, as well as for Quacula (yes, a vampire duck). Each episode had one Quacula short, two Heckle & Jeckle shorts, and three spots for Mighty Mouse, one of which would be an installment of an ongoing serial called “The Great Space Chase.” In 1980, the show was cut to half an hour, and eventually moved to Sunday, before ending. The Great Space Chase theatrical film of 1982 was edited together from the 16 parts of the completed serial.

Mighty Mouse didn’t stay away from CBS for long. Famed animator Ralph Bakshi, who started his career and Terrytoons before becoming known for edgy animated features like Fritz the Cat, Wizards, and American Pop, as well as his 1978 adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, kicked off a revival series in 1987. Titled Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures, the series drew critical acclaim for its new style and more sophisticated humor. Those elements could be owed in part to Bakshi, and to first season senior director John Kricfalusi, who would create Ren & Stimpy. The series even made Time’s list of the Best of 1987. Unfortunately, the show came under attack by Donald Wildmon’s American Family Association, who alleged that one episode where Mighty Mouse sniffed a flower depicted cocaine usage. The fairly ludicrous story played out in the press, and though CBS released statements supporting Bakshi, the show was cancelled by 1989.

Mighty Mouse has mostly been out of the spotlight since that time, but rumblings of a reboot continue. In 2019, Paramount Animation began assembling a team for a hybrid live-action/CGI feature; writers Jon and Erich Hoeber and producers Karen Rosenfelt and Robert Cort are reportedly attached. As of November 2, 2020, the film was scheduled for an October 2022 release.

Whether the super-powered mouse grabs the attention of a new generation of fans remains to be seen. But just because he’s been in the background for a couple of decades, don’t count Mighty Mouse out. It could be on the big screen, or maybe on Paramount’s streaming service, but chances are good that he’ll be coming to save the day once again.

Featured Image: Still frame from Wolf! Wolf! From 1945. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Superraton.jpg (©CBS/Terrytoons via Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain)

The Debate Over the First TV Commercial

This much is certain. Ninety years ago this week, W1XAV in Boston, Massachusetts transmitted television video over the airwaves from The Fox Trappers. That orchestra program originated from CBS Radio, but was being shown on that upstart medium, television. During the course of the program, viewers caught an ad for the show’s sponsor, I.J. Fox Furriers. Or did they? The question seems to echo through TV history.

It might sound crazy, but there really was television in 1930. Though the medium would be widely popularized through the 1939 World’s Fair and not explode for some time, TV stations had already started to pop up around the country, broadcasting in their earliest forms. W1XAV in Boston was actually the city’s second station; it opened in 1929. Radio sponsorships were already a familiar form of advertising, with many programs carrying sponsors whose financial support kept them on the air. Such was the case with The Fox Trappers and their I.J. Fox Furriers sponsorship. When the program ran on TV, so did the identification of sponsorship.

The Bulova watch ad (Uploaded to YouTube by Illume Mtn)

However, to the minds of many critics and historians, that doesn’t really make the Furriers spot the first official commercial in the history of TV. That distinction has been awarded by many to a Bulova watch commercial that didn’t air until 1941. By this time, TV was making much deeper inroads, and the ad ran prior to the start of a Major League Baseball game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Philadelphia Phillies. The ad only ran a few seconds; it showed a clock face with a moving hand, offset by a ticking effect and a quick slogan. The station, New York’s WNBT (WNBC today), charged a mere $9 to run the ad; they assessed $5 in “station charges” and $4 in “air charges.”

Most TV historians believe that the Bulova ad is the official first because it was a commercial specifically produced for the medium of television. The I.J. Fox spot was a sponsorship announcement crafted for radio that just so happened to be carried over the TV airways. Even though it happened over a decade earlier, many observers call the Bulova ad first purely on intent.

The idea that a TV ad for a sporting event would only cost $9 is incredibly quaint today, given that a Super Bowl ad spot in 2020 cost $5.6 million. With the proliferation of streaming channels, we may have already seen the absolute peak of spending for television advertising; that would have been 2018, during which the industry topped $72 billion spent on TV ads.

The new question facing advertisers is how to contend with the new streaming reality. While ad placements are obviously part of network and recorded shows on venues like Hulu, other streamers like Prime Video and Disney+ eschew the practice entirely. Netflix has been noted for significant brand placement within its programs. It’s possible that deals could be struck where streaming favorites are brought to you by a single sponsor (something that Fox experimented with in 2018, when a Family Guy episode sponsored by PlayStation ran with no ad breaks), which would play into an old adage, and a favorite of ad people, “Everything old is new again.”

Featured Image: RCA Model 630-TS television set; mass produced in the 1940s. (Photo by Fletcher6 via Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

5 Things You Didn’t Know About Monday Night Football

Monday Night Football kicked off 50 years ago this week. The broadcast was a crucial component in establishing the NFL as a dominant ratings force and making it the most-watched sporting league in the United States. Prior to its move to ESPN in 2005, MNF was one of the longest-running prime-time shows in the history of network TV. With a new season underway, here are five things you didn’t know about Monday Night Football.

1. It Has Hosted More Than 700 Games

Throughout the 50 seasons of Monday Night Football, the series has played 718 games as of September 21, 2020. The very first game saw the Cleveland Browns host the New York Jets. The Browns won 31-21 in a game that was watched by 33 percent of the total American viewing audience for that evening.

2. Gifford Had the Chair Longer Than Anyone

Howard Cosell remains the most famous original commentator; he held his spot for 13 years. Frank Gifford joined in the second season, and his run lasted until 1998, making him the commentator who was with the show the longest with a total of 27 years. There have been about 40 play-by-play announcers and color commentators across the history of the program on ABC and ESPN; the current team consists of Steve Levy, Brian Griese, and Louis Riddick. There have been dozens of sideline reporters and more than a dozen radio commentators; the current radio team is Jim Gray, Kevin Harlan, and Kurt Warner.

3. Famous Guests Have Hit the Booth

Over the years, a number of celebrities dropped by the broadcast booth. Visitors have included Kermit the Frog, Richard Nixon’s first vice-president Spiro Agnew, and President Bill Clinton. On December 9, 1974, both John Lennon and Ronald Reagan were in the both at the same time. Sadly, just six years later on December 8, 1980, Lennon was shot and killed in New York City. Cosell broke the news to most of America near the end of a Monday Night game between the New England Patriots and Miami Dolphins.

4. It Took Over American Sports and Went Global

MNF was firmly entrenched in the Top Ten of the weekly broadcast ratings for years, becoming one of the most popular shows in America. It elevated football to the position of the most-watched sport of the big three in the States, dethroning Major League Baseball as the favorite and holding off NBA basketball even at its biggest. The show is carried in Europe, Australia, and South America. ESPN has American broadcast rights, including streaming, through 2021. As of August, ESPN is looking to improve the deal for an extension.

5. Monday Night by the Numbers

The most-watched game ever was the Miami Dolphins versus the Chicago Bears on December 2, 1985. The Dolphins ruined the Bears’ shot at a perfect season, handing them their only regular season loss; the Bears would go on to win the Super Bowl (while, one presumes, doing the “Super Bowl Shuffle”). The Dolphins, however, take the title of Most MNF appearances (their 85th appearance is this season). The highest scoring game ever was in 1983 when the Green Bay Packers and the now-titled Washington Football Team ran up a combined 95 points.

The full “Monday Night Miracle” game (Uploaded to YouTube by the NFL)

MNF has been the stage for some amazing comebacks. One of the most popular came in 2003 when the Indianapolis Colts were down 35-14 against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Colts quarterback Peyton Manning engineered a comeback with four minutes left on the clock to tie the game; Colts kicker Mike Vanderjagt kicked a winning field goal in OT, giving the Colts a 38-35 win. However, only one game is called the “Monday Night Miracle,” and that honor goes to the October 23, 2000, game between the Jets and the Dolphins. The Jets scored a seemingly impossible 30 points in the fourth quarter, tying the game and sending into OT; when it was all over, the Jets had squeaked by 40-37.

Featured image: pixfly / Shutterstock

The Mary Tyler Moore Show Remains a Television Landmark

It’s easy to say that a show redefined television, but it’s much harder to prove. In the case of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, you might say that the proof is all around. The series recreated the mold of the ensemble comedy. It changed the way that comedy shows were directed. It had a cast that was strong enough to spin off three separate characters into their own series (one of which was a drama!). And it wasn’t afraid to engage in very serious topics, including some that were taboo for the time. The show still shows up on “Best of” lists, including best writing, acting, and direction, as well as Best Finale and Funniest Moment (seriously, the Chuckles funeral). It’s a program where everything still holds up remarkably well five decades later. That’s right; The Mary Tyler Moore Show launched 50 years ago, and TV is much better because of it.

Series co-creator Allan Burns started writing in animation, working on Jay Ward productions like The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show. He co-created The Munsters and worked as a story editor on Get Smart. James L. Brooks broke into TV news in the 1960s on the writing side. Brooks met Burns at a party, and Burns got him TV writing work. After working on several shows, Brooks created Room 222; when he left after the first year to develop other projects, he got Burns to come aboard as producer. Soon after, Grant Tinker, a programming executive at CBS, hired the duo to create a show for his wife. His wife happened to be Mary Tyler Moore, who was already beloved and famous for her long-running role as Laura Petrie on The Dick Van Dyke Show. Leaning on Brooks’s background, they decided to build the show around the goings-on in a metropolitan TV newsroom with Moore’s Mary Richards as the associate producer at the center.

Mary Tyler Moore on casting (Uploaded to YouTube by FoundationINTERVIEWS)

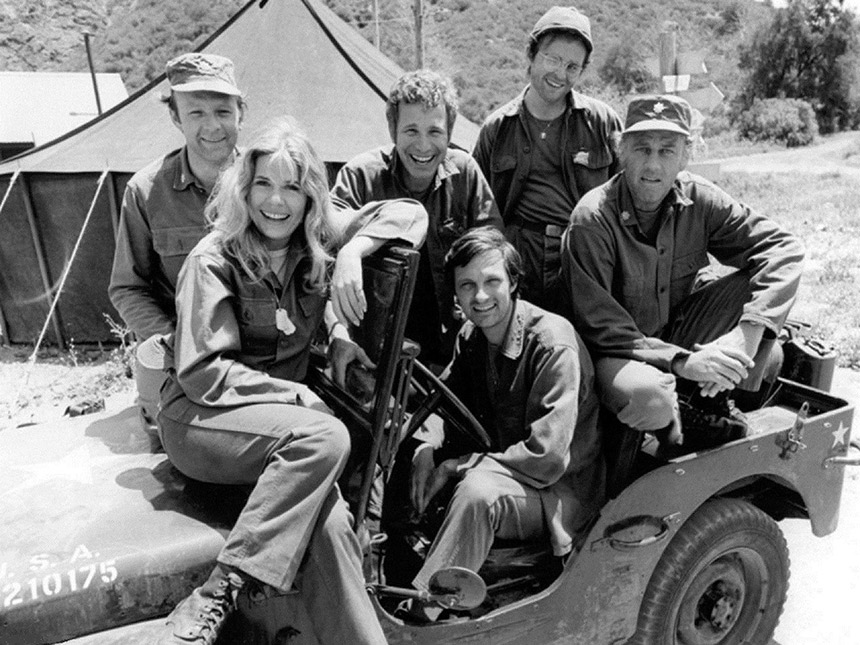

The nucleus of the newsroom cast was Moore, Ed Asner, Gavin MacLeod, and Ted Knight; Valerie Harper and Cloris Leachman played Mary’s best friend, Rhoda, and neighbor, Phyllis, respectively. Over the years, as Harper and Leachman left for spin-offs devoted to their characters, the cast would add Georgia Engel and Betty White to great effect. The Mary Tyler Moore Show managed to be both entertaining and relevant. Mary Richards was single throughout the tenure of the show, and not forcing the character to be defined by a man or relationship was groundbreaking. Similarly, Rhoda grappled with body image issues. No character was one-note; even Ted Knight’s Ted Baxter, for his incompetent bluster, had moments of humanity and deepened further when Engel’s Georgette was added to the cast as his wife. The shading of each character, rather than simply assigning a type and relying on it, became a sitcom staple.

While the actors made it all work, the writing and directing had a great deal to do with it. Brooks would apply the dynamics of ensemble building to shows like Taxi and The Simpsons. When you watch an episode like “Chuckles Bites the Dust,” you’re witnessing something akin to an eight-sided tennis match; each character is bouncing jokes and responses back and forth, but the jokes are all rooted in that particular actor’s character. When Mary can’t control her giggles during the clown’s funeral, and later bursts into tears, it’s funny because a) it’s funny, b) it’s believable human behavior, c) it’s all true to what we know about Mary, and d) it’s deeply relatable. If you’re thinking that the same principles apply to many episodes of the show, you’d be right.

Another important facet of the show was the fact that it didn’t turn its back on difficult topics in society. Like the aforementioned personal struggles that Mary and Rhoda had, characters faced personal difficulties or were involved in plots that brought up issues of the day (and today). One memorable moment came in the episode “You’ve Got a Friend;” when Mary’s visiting mother told Mary’s father not to forget to take his pill, he and Mary both replied, “I won’t,” implying, of course, that Mary was on birth control. The show also addressed equal pay for women and many more storylines that remain relevant today.

As the show went on, appreciation for it grew. It pulled in 29 Emmys, including three for Outstanding Comedy Series in 1975, 1976, and 1977. Moore also won three times for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. It was a solid Top 20 entry in the ratings for most of its run, with three years spent in the Top Ten. When the show received a Peabody Award in 1977, it came with the state that the show had “established the benchmark by which all situation comedies must be judged.” Since the show’s end after its seventh and final season, it has routinely placed on lists recounting the best in television, including lists from TV Guide, Entertainment Weekly, and USA Today. In 2013, the Writers Guild of America put it number six on their list of the best written television series of all time.

After the series ended in 1977, a third spin-off, Lou Grant, was launched. Ed Asner led the series for five seasons, during which it won 13 Emmys, two Golden Globes, and its own Peabody. Plans were made for Mary and Rhoda to reunite in a sitcom; however, those were later abandoned. Mary and Rhoda did meet up again in the 2000 TV movie Mary and Rhoda. A 2002 reunion special brought the entire surviving cast back together (Knight had passed in 1986) for a retrospective look at the series. Today, all seven seasons are available to watch on Hulu.

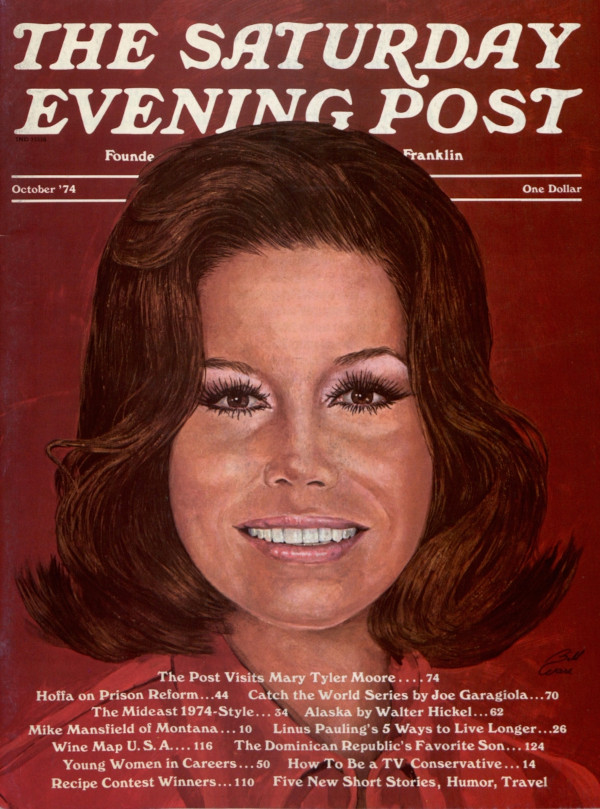

After the series, Moore worked continuously across film, television, and theater. She earned an Oscar nomination for her role in 1980’s Ordinary People. She and Tinker divorced in 1981, and she married Robert Levine in 1983. A type 1 diabetic, Moore served for years as the international chairperson for the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. She was also active in animal rights and in the restoration and preservation of Civil War history. Moore passed way in 2017 at the age of 80.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show left an indelible mark on television. You can see its DNA in everything from Cheers to Friends to The Office. Any show with a workplace at the center is bound to be compared to it, and any show that features adults talking to each other like adults recalls its boldness. Few shows are daring enough to make you laugh at a clown’s funeral; far fewer could make it one of the most memorable scenes in TV history. A classic by any measure, the show’s impact likely never go away. It certainly made it, after all.

During the run of the show, the Post went behind-the-scenes with Moore in a wide-ranging interview from 1974. You can read that story below.

Featured image: Cast photo from the television program The Mary Tyler Moore Show. After the news that most of the WJM-TV staff has been fired, everyone gathers in the newsroom. From left: Betty White (Sue Ann Nivens), Gavin MacLeod (Murray Slaughter), Ed Asner (Lou Grant), Georgia Engel (Georgette Baxter), Ted Knight (Ted Baxter), Mary Tyler Moore (Mary Richards). (Publicity Image from CBS Television; Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

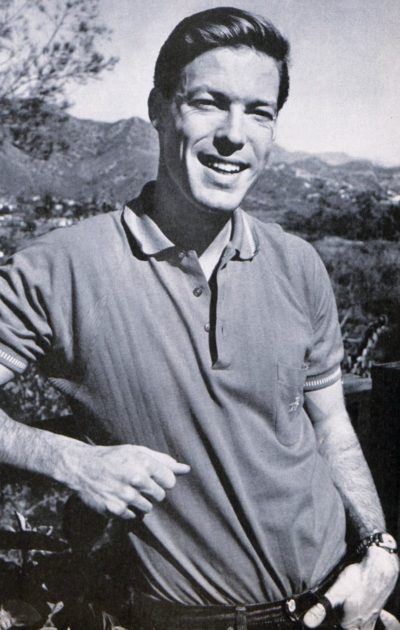

50 Years Ago, Flip Wilson Changed the Face of TV Comedy

Flip Wilson started working his way up the comedy ranks in the 1950s, but his big break came in 1965. That’s when Red Foxx told Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show that Wilson was the funniest comedian out there. Carson put him on, and stardom followed. Within five short years, Wilson was at the helm of his own variety and sketch-comedy show, The Flip Wilson Show. The trailblazing series saw Wilson become one of the most visible and popular Black entertainers in America. On the 50th anniversary of its first episode, here’s a look back at Wilson’s journey and how his show became a platform that propelled other artists forward.

Clerow Wilson Jr. was born in 1933. His mother left his father, him, and his nine siblings when he was seven; as a result, Wilson and a number of his siblings went to foster homes. Wilson joined the Air Force when he was 16 (yes, he lied about his age). Wilson’s natural instincts for entertaining emerged, and his gift for comedy soon saw him sent from base to base to improve morale. Some of his fellow servicemen would describe him as “flipped out” and called him Flip. Wilson would adopt that name and perform under it for the rest of his career.

Flip Wilson on The Ed Sullivan Show from 1970 (Uploaded to YouTube by The Ed Sullivan Show)

After the Air Force and into the early 1960s, Wilson built his comedy brand. He recorded a pair of albums, Flippin’ (1961) and Flip Wilson’s Pot Luck (1964) during this period as he performed in clubs. He also appeared regularly at the Apollo Theater. When Redd Foxx endorsed him to Johnny Carson, it facilitated his entrance onto television. In addition to multiple appearances on The Tonight Show, Wilson would appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, The Dean Martin Show, Here’s Lucy, and more. With the launch of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In in 1968, Wilson was billed as a “Regular Guest Performer” through the first four seasons.

Wilson’s growing popularity earned him a shot with his own show. The Flip Wilson Show debuted on September 17, 1970, on NBC. The program incorporated sketches along with music and celebrity guests. Wilson played a variety of recurring characters. Easily the most famous was Geraldine Jones, his take on a modern Black woman from the South. Geraldine turned out to be something of a catchphrase machine, with lines like “The Devil made me do it,” “What you see is what you get,” and “When you’re hot, you’re hot; when you’re not, you’re not” entering the cultural vocabulary.

Flip Wilson on The Midnight Special (Uploaded to YouTube by Midnight Special)

Wilson used the show as a platform for a number of other Black performers. The show included early appearances by the Jackson 5 and welcomed stalwarts like Aretha Franklin, The Temptations, The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, and more. He also brought on a wide range of other guests, featuring everyone from Johnny Cash to Bing Crosby to Joan Rivers. Musical guests also frequently took part in the comedy bits. Among Wilson’s writers was legendary comic George Carlin, who himself was in the midst of a turn toward more countercultural comedy; Carlin occasionally appeared on the show as well.

In a short period of time, The Flip Wilson Show was one of the most watched programs in America, falling behind only All in the Family in 1971. It was a groundbreaking success, as Wilson became one of the few Black entertainers to be that popular with white audiences as well. The show was also recognized for its overall quality; it won two of eleven Emmy nominations and earned a Golden Globe for Wilson for Best Actor in a Television Series. Wilson’s fame grew, but the network began to resist his demands for a larger salary. As the show went on, ratings dipped (as they did for most prime-time variety shows of the period), and the series was cancelled in 1974.

Eddie Murphy and Jerry Seinfeld discuss the greatness of Flip Wilson and other comics (Uploaded to YouTube by Netflix Is A Joke)

Wilson worked regularly in comedy, television, and film over the following years. In 1983, he memorably hosted Saturday Night Live; he even played Geraldine in a sketch that “revealed” her to be the mother of Eddie Murphy’s hairdresser character, Dion. Wilson headlined the TV show People Are Funny in 1984 and was the lead in Charlie and Co. from 1985 to 1986. His last television appearance was on a 1996 episode of The Drew Carey Show. Wilson passed away from liver cancer in 1998 at the age of 64.

Wilson reached all audiences with his humor and put acts in front of audiences that might not have seen them otherwise. His influence extended into the way Americans talk; even the editing software WYSIWYG is an acronym taken from one of Geraldine’s catchphrases. He earned the admiration of comedians like Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor, worked to get the best facilities for his show, and wasn’t afraid to demand compensation commensurate with running and starring in the #2 show on television. If what we saw was what we got, then we got greatness.

Featured image: Flip Wilson as Geraldine Jones interviews Dr. David Reuben on an episode of The Flip Wilson Show (Wikimedia Commons)

San Diego Comic-Con Still Reigns

“Hey, it’s the second-best writer at Newsarama.”

To her credit, Vaneta did not hit me. She turned around, saw it was me, and gave me a hug. Then she hit me (okay, just in the shoulder). We were on the crowded main floor of the 2007 San Diego Comic-Con. We talked briefly about what we were covering; I was pulling double-duty, working for both Newsarama.com and as an associate editor for Fangoria Comics, a spin-off of the vaunted horror magazine. I’d spent so much time working on Fangoria stuff and making connections to get there from the Midwest that I hadn’t really paid attention to other things that were going on, aside from what I’d be assigned to cover.

Then Vaneta said, “Downey’s here.”

That surprised me a little. We all knew that Robert Downey Jr. had been cast as Tony Stark in the forthcoming Iron Man, but I was still a little surprised that he would hit the show. Sure, other actors and directors had done the same thing in previous years (in fact, Robert Rodriguez was there that year for his and Quentin Tarantino’s Grindhouse), but this seemed different. It was indicative of the changing perception of what SDCC was, both to the entertainment industry and the outside world.

Flash-forward to today: Comic-Con International: San Diego marked its 50th year in 2020. What should have been a grand celebration instead had to shift online under the specter of COVID-19. Nevertheless, the fact that the event adapted and continued is a tribute to its pioneering spirit and its ability to change, morphing from a one-day show called the Golden State Comic Book Convention in March of 1970 before trying out a three-day format 50 years ago this week.

The original show was founded by Shel Dorf, Ken Krueger, Mike Towry, Richard Alf, Bob Sourk, Greg Bear, and Barry Alfonso. Dorf had run some of the first comic book conventions in the 1960s in Detroit before moving to California. The March 21, 1970, Golden State Comic-Minicon was Dorf’s notion of a test flight for a larger show. The Golden State Comic-Con ran from August 1 to 3, 1970. Total attendance was around 300 people.

As the show grew, it shifted through different venues and underwent a series of name changes. It was San Diego’s West Coast Comic Convention in 1972 before becoming San Diego Comic-Con in 1973. Since 1995, the event has been properly called Comic-Con International: San Diego, though many still refer to it as San Diego Comic-Con, SDCC, or, simply, San Diego. (If you say San Diego in a comic book store, they know you aren’t talking about the Padres.) The event itself is organized as a non-profit, and owns registered trademarks on the phrases “Comic-Con” and “Comic-Con International,” which has led to several other shows changing their names in the past several years (with “Comic Convention” or “Comic Fest” being the most frequent substitutions).

From the outset, the founders intended the show to be more than just comics. Creators and fans of science fiction and fantasy literature and film were welcomed from the beginning. In fact, co-founder Bear is an award-winning genre author of more than 50 books. In 1976, Roy Thomas and Howard Chaykin went to the show to promote a new Marvel comic that they were doing, an adaptation of a film that was due out in 1977. They only had a few stills to show to a tiny crowd. Still, it did make the attendees excited about that new movie. It was called Star Wars.

Over the years, as comic shops proliferated, the business boomed, and books like The Uncanny X-Men began to move insane numbers in the 1980s, San Diego got bigger and bigger. What was once an event that attracted 300 people began to attract thousands, then tens of thousands, then one hundred thousand. The mix of fans, creators, exhibiting companies, cosplayers, and occasional film and TV personalities made a potent brew. For years, the show has hosted both the Inkpot Awards, given to outstanding contributors in the genre fields, and the Will Eisner Awards, which are essentially the Oscars of comics. Yes, there were and are other fine conventions around the country, like North Carolina’s Heroes Con or Mid-Ohio Con or New York Comic Con or Chicago’s C2E2, but there has only ever been one San Diego.

I’d attended or worked at other cons before, but when I got the chance to go to San Diego, it was different. I felt like I was commuting to the beating heart of the pop culture universe. It was a veritable sea of people (attendance was reputedly 125,000 in 2007). It took almost thirty minutes to walk from one side of the main room to the other, and that’s if you didn’t stop. Fangoria hosted actor Michael Madsen (Reservoir Dogs, Kill Bill, etc.) for a signing that year, and I took one of his sons out on the show floor to shop for Star Wars toys. We went to parties for Troma Films and Rue Morgue magazine. A couple of Fango friends and I caught a ride with Ken Foree, the star of George Romero’s horror classic Dawn of the Dead. We exchanged pleasantries in a hotel lobby with Buffy the Vampire Slayer creator Joss Whedon (ironic considering that the MCU was launching that weekend and he’d be back in a few years, announced by Downey as the writer and director of Avengers). It was most certainly surreal.

The unique thing about my SDCC experience is that there was almost nothing unique about my experience. The show is a bright, candy-colored circus for almost everyone who goes. Yes, conventions in general have struggled with issues related to cosplayer safety, and San Diego in particular can be a nightmare when it comes to securing hotel rooms and admission, but the fact remains that as an entity, there’s not much that’s quite like it.

In 2008, which I did not attend, the Twilight Saga made a big splash. A panel for the second film, The Twilight Saga: New Moon crammed 6,000 attendees to see clips from the film and a panel with the cast. Over the next few years, attending fans of that series increased in numbers, leading to grumbling in some quarters about a perceived dilution of the show. Really, though, the disgruntlement seemed to be based on two things: the clogged exhibit hall areas caused by fans trying to jockey for position many hours ahead of the panel (which, okay, fair) and the fact that Twilight appealed primarily to women and girls (absolutely not fair at all). The success of Twilight at SDCC actually proved that the show could be a bigger tent and welcome fans of diverse genres and properties, as well as diverse fans.

It might be fair for hardcore comic fans to feel a bit like the comics themselves have been marginalized at the show. The biggest reserves of press coverage focus on movie announcements and actor appearances. It’s a hard place to launch a new comic, as a vacuum of overwhelming P.R. tends to swallow smaller pieces of information. But looking too hard in that direction is a denial of the success that the show has become. That stuff that you liked, that stuff that you might have been made fun of for loving? Lots and lots of people like that stuff now, too. Celebrate that, instead of being put off by the fact that more and different people are at the show.

As you know, crowding wasn’t the problem this year. SDCC mounted “Comic-Con@Home,” a virtual effort with remote panels, online exclusive products, watch parties, and more. It was a valiant effort that contained some great virtual events, but of course, not the same. If all goes well in the world, it’s possible that Comic-Con International: San Diego could return next year. The important thing about this show is the same thing that is important about GenCon or any other celebration of fandom: it’s cool to love what you love. And it’s cool that other people get to, too.

Featured image: Sarah Mertan / Shutterstock

What’s Bugging Andy Griffith?

Originally published January 24, 1964

Griffith is a fearsome worrier, so petrified by social situations that he avoids most big Hollywood functions. “I feel I just might not be able to cope,” says Griffith. “I wish I could be like [Sheriff] Andy Taylor. He’s nicer than I am — more outgoing and easygoing. I get awful mad awful easy.” Griffith freely admits to what seem to him monumental shortcomings, among them a tendency to keep public emotion at arm’s length. “It’s the way we mountain people are,” he tries to explain.

“My own grandpappy never showed big emotion but once in his life. Lying on his deathbed, he suddenly got up and kissed my grandma gently on the check — he’d never been seen before even to touch her! Then he took back to his bed and died. One emotional act in his whole life, but no one ever forgot it.”

When Andy looks back on his childhood, he sometimes assumes a prismatic double vision. One moment he recalls “the fun we kids had in the summer kickin’ rocks and lyin’ to each other in that wonderful slowed-down time between dusk and dark.” In the next, he speaks of himself as a skinny, gawky, rejected, unathletic kid hurt by his nickname of “Andy Gump” [a cartoon character] and remembers that once, when he was 11, someone called him “white trash.”

As he expands as a man and an actor, Griffith thrives in what another rural comic, Pat Buttram, has called the best of all possible worlds — “a Southern accent with a Northern income.”

Once, aboard an airliner, Griffith turned to his manager. “Say, you think I oughta lose my Southern accent?” he asked seriously.

“Sure,” the other shot back, “if you want to try another line of work.”

—“I Think I’m Gaining on Myself” by Donald Freeman, January 25, 1964

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: PictureLux / The Hollywood Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Coming Around Again: The Longest Running (and Longest Gaps Between) Hits

To say that 2020 has been an odd year would be an understatement on the order of “The Beatles were mildly popular.” One of the places that the strangeness of our lockdown year has been reflected has been at the movies. With regular theaters closed, drive-ins surged, frequently playing older films. That resulted in the unusual case of 1993’s Jurassic Park hitting the top of the box office again in June. That phenomenon leads to the following questions: what are the biggest gaps between chart toppers, whether at the box office, the record charts, or elsewhere, and what are the film and TV series that have stuck around the longest?

1. When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth

Jurassic Park stomped to #1 for three weeks upon its initial release in 1993. On June 22nd, lifted by drive-ins, the film took the top spot again 27 years after its original ride. Gone with the Wind remains the all-time box office champion if you adjust for inflation, and the 1939 film had three official re-releases (1989, 1998, 2019), but none of them cracked the #1 spot.

2. Cockroaches and Cher

There’s an old joke that goes that if there’s ever a nuclear war, all that’s left will be cockroaches and Cher. While that’s a loving, tongue-in-cheek tribute to the star’s longevity and resiliency, it also has a ring of truth to it where the charts are concerned. Cher hit #1 for the first time in August of 1965 with her then-husband Sonny Bono on their classic “I Got You Babe.” After a continuous run of hits throughout the rest of the 1960s, the 1970s (with three solo #1s), the 1980s, and the 1990s, Cher took “Believe” to #1 in March of 1998. That’s an amazing 33-year-and-seven-month gap between her first #1 and her most recent #1.

Other prodigious gaps between first and most recent #1s have been held by George Harrison (23 years and 11 months between “I Want to Hold Your Hand” as a Beatle in 1964 and “Got My Mind Set on You” in 1988), The Beach Boys (24 years and 5 months between “I Get Around” and “Kokomo”), Elton John (24 years and 8 months between “Crocodile Rock” and “Candle in the Wind 1997”) and Michael Jackson (25 years and 8 months between “I Want You Back” with The Jackson 5 and “You Are Not Alone”).

3. His Name is Series, Longest-Running Series

While the overall continuity of the James Bond series is in question, everyone generally treats the films as if they’re part of an ongoing mega-series. It’s the third-highest grossing franchise in movie history, behind only the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars. But the biggest weapon that Q never designed is Bond’s insane longevity. The first film, Dr. No, was released in October of 1962. If No Time to Die keeps its adjusted November 20, 2020 release date, then that will be 58 years and one month between the first and most recent installments of the series.

4. Call The Doctor!

Another British favorite that will seemingly go on forever is Doctor Who. There’s no question about Who continuity; everything is fair game, particularly when your main character is a regenerating Time Lord that is simply the same character in a new form with each re-casting. The Doctor’s first adventure aired in 1963. The original series ran uninterrupted until 1989. A TV film aired in 1996. The series restarted in earnest in 2005 and has been running ever since. The most recent season ended in March of this year. While the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has put production dates everywhere in question, a special, “Revolution of the Daleks,” should air around the holidays, and the next season is generally expected to air beginning in 2021. If you simply use today as the metric for how long the single continuity of Doctor Who has been running, that’s 57 years of adventures in space and time.

5. Hang on, Marshal Dillon; Detective Benson Is Here

For many years, the issue of the longest-running drama on prime time American television wasn’t a question. That was Gunsmoke, which ran from 1955 to 1975. In 2019, that record was passed by Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, which started in 1999 and is ongoing at present; in fact, NBC has already given it a blanket renewal through a 24th season. The longest-running prime-time program overall is animated comedy The Simpsons, which launched in 1989 and is still running.

On the daytime side, the Guiding Light still holds the record for longest running daytime drama with 57 years on the books at its 2009 sign-off. That record will fall to General Hospital in the very near future. Had it not been for the interruption in production brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, GH would have passed it this summer. At the moment, a hard pass date can’t be established until production resumes.

6. Seriously, I Was Writing the Whole Time

Some writers seem to function at an inhuman level of output. For every George R.R. Martin, who takes years between A Game of Thrones installments, you have his pal Stephen King, who has averaged 1.4 novels a year since 1974 (plus 11 short story collections, 19 screenplays and five nonfiction works). Then you have the entirely opposite end of the spectrum where dwell writers that have a literal lifetime between their first and second novels. The big winner there is Harper Lee; 55 years passed between the release of To Kill a Mockingbird and Go Set a Watchman. On the technical level, the issue of what to call Watchman exactly is the subject of some debate; yes, it’s a novel, but it’s also really the first draft of what would become Mockingbird.

If you’re looking for the longest gap between an original novel and its sequel, then King might hold the record. It’s true that 59 years passed between the publication of Upton Sinclair’s King Coal and the follow-up The Coal War. However, Sinclair finished the sequel in 1917; the publisher didn’t want to put it out and it sat until 1976, eight years after Sinclair’s passing. King’s gap comes between the 1977 publication of The Shining and its sequel, 2013’s Doctor Sleep, which hit stores 36 years later.

7. Another Day in the 87th Precinct

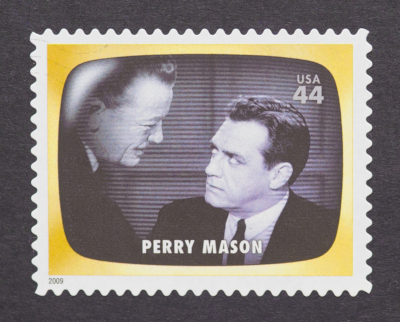

When it comes to the longest-running series of novels, there are quite a few qualifiers involved. Some novels are franchises given over to other writers, or are based on characters owned by companies rather than individuals. That might account for characters like Doc Savage or Remo Williams/The Destroyer, that have hundreds of novels under their fictional belts. Then you get into series, like Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, with 40 books, or Agatha Christie’s 38 books centered on Hercule Poirot, or the exploits of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe in 49 books. Erle Stanley Gardner produced 82 Perry Mason mysteries between 1933 and 1973.

But the longest sustained series by one author appears to be the 87th Precinct series of novels by Ed McBain, which is the pseudonym of Evan Hunter. Between 1956 and 2005, McBain put out 54 novels that take place in one overarching continuity. Set in the city of Isola, a fictional analogue of New York City, the novels follow the cases of the Precinct, most of which involve Detective 2nd Grade Steve Carella.

It seems appropriate to give a mention here to Sue Grafton. From 1982 to 2017, she published “The Alphabet Mysteries,” a series featuring her detective Kinsey Millhone. The books were designed to be a series of 26, one for each letter of the alphabet (A is for Alibi, etc.). The series ran for 35 years. Unfortunately, Grafton passed away in 2017 before beginning the planned Z is for Zero. As opposed to writers like Robert Jordan, who worked with others to see that his Wheel of Time series would be completed after his death, Grafton disdained the idea of having a ghostwriter finish the series. In the Facebook post that announced her mother’s passing, Grafton’s daughter Jamie wrote, “Many of you also know that she was adamant that her books would never be turned into movies or TV shows, and in that same vein, she would never allow a ghost writer to write in her name. Because of all of those things, and out of the deep abiding love and respect for our dear sweet Sue, as far as we in the family are concerned, the alphabet now ends at Y.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Case of the Return of Perry Mason

“The Case of the Return of Perry Mason” instantly seemed the obvious and appropriate title for this feature. After all, this coming Sunday sees the return to television of one of the longest-standing characters in modern American media in a brand-new HBO series. And “The Case of”? Well, that’s obvious, too; all of the Perry Mason novels and films and TV episodes began with that. Here’s where it seems kind of funny, though: Perry Mason would have had to have gone away to return. As it stands, the character and his supporting cast have been part of American popular culture for nearly a century. It would seem that this makes this “The Case of Perry Mason and How He Became an Icon.”

The author of the Perry Mason books, Erle Stanley Gardner, published his first story in 1923. His original vocation, that of a trial lawyer, had started to bore him. Nevertheless, his predilection for defending immigrants and others at the mercy of the system would certainly inform his work in his second field. The prolific Gardner established a number of pseudonyms so that he could contribute more stories to various outlets; among his regular markets were Argosy, Black Mask, Detective Fiction Weekly, and, later on, The Saturday Evening Post. Gardner would eventually leave his law firm in 1933 upon the publication of his novel The Case of the Velvet Claws.

That novel is notable as the first appearance of defense lawyer Perry Mason, his assistant, Della Street, and his good friend and private investigator, Paul Drake. In that first book, Mason outlines his mission statement, describing himself as “a specialist on getting people out of trouble.” Outside of Mason’s legal brilliance and propensity for clearing his clients by producing a confession from the guilty party, you don’t learn a whole lot of Mason’s private life at all. That doesn’t change much over the course of the 80 Mason novels that Gardner wrote between 1933 and 1970. It may also be part of his appeal; his forthright protection of his client and his investigations with his two dedicated partners are backstory enough.

Mason proved instantly popular — enough for Hollywood to come calling. Warner Bros. knocked out six Mason films between 1934 and 1937, four of which starred Warren William in the lead. Claire Dodd played Della twice; in a strange divergence from novel continuity, the film series saw Mason and Della get married. Weirdly enough, another Mason novel was adapted in 1940 under a different title. The Case of the Dangerous Dowager was adapted as Granny Get Your Gun, but the film discards Mason and his regulars in favor of being a wacky comedy.

Radio beckoned, so the stories were adapted into the CBS Radio series Perry Mason. Each episode was 15 minutes long; the hugely popular show ran from 1943 to 1955. By 1956, CBS wanted to transition the show to television. When they pitched Gardner on the idea of making it a daytime serial that he would write, he balked, particularly at the network notion of giving Mason love interests. He withdrew from the idea, taking Mason with him. However, Mason radio writer Irving Vendig wrote a pitch that starred basically a copy of Mason, and that became The Edge of Night. The mystery flavored soap was popular in its own right and ran from 1956 to 1975 on CBS; in 1975, it jumped over to ABC and ran until 1984, 28 years in all.

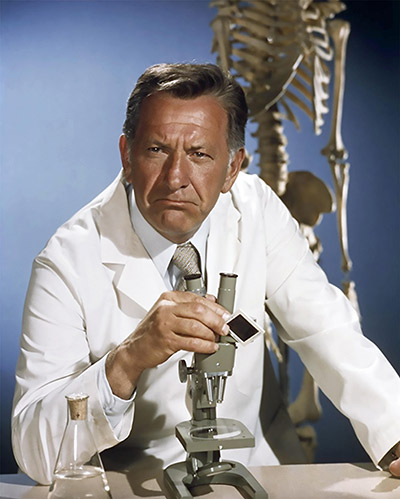

CBS wasn’t quite done with Mason, so they went back to Gardner with the idea of doing a prime-time series that retained the original flavor of the character. Gardner agreed, and the Perry Mason TV series was born. The executive producer was Gardner’s friend, Gail Patrick Jackson; she, her husband Thomas Cornwall Jackson (Gardner’s agent), and Gardner formed the production company Paisano Productions. Gardner sold an option to CBS on 272 of his stories and a dozen major Mason characters through the production company; the deal provided that the partners own 60 percent of the show. Casting was laborious, but Gardner loved the guy chosen for Mason, actor Raymond Burr; the other lead roles were filled out by Barbara Hale as Della Street, William Hopper as Paul Drake, and William Talman as Mason’s frequent courtroom antagonist, L.A. D.A. Hamilton Burger.

The show was a massive success. During its 1957 to 1966 run, it was one of the most popular shows on TV. It won an Emmy for Best Dramatic Series in its first season, and would net two for Burr and one for Hale over its run. Its theme by Fred Steiner is one of the most familiar on television. 67 of the 69 Mason novels that Gardner wrote before 1963 were adapted into episodes of the show. Gardner had daily involvement with the show, reading and approving scripts and showing particular interest that matters of law were represented with accuracy; he also played a judge in the final episode of the series, “The Case of the Final Fade-Out.” The show was cancelled by CBS in 1966, despite its ongoing popularity.

CBS tried to reboot the series in 1973 with a new cast, but it flamed out after half a season. Fortunately, Gardner didn’t see it. The incredibly prolific writer and staunch defender of his characters had died in 1970.

In 1985, producer Dean Hargrove took on the task of bringing Mason back to TV in a series of TV movies for NBC. At the time, he was known for his work on The Man from U.N.C.L.E., McCloud, and Columbo. Hargrove managed to get Burr and Hale back as Mason and Street; unfortunately, William Hopper had passed away in interim. Hargrove had the inspiration to cast Hale’s real-life son, William Katt (best known for The Greatest American Hero) as Paul Drake Jr., carrying on his dad’s role as Mason’s right-hand man. Burr and Hale made 26 TV movies between 1985 and 1993; Katt stuck around for nine, and was replaced by new character Ken Malansky, played by William R. Moses. Burr died in 1993, but they retitled the films as A Perry Mason Mystery and had guest actors like Paul Sorvino and Hal Holbrook play fill-in characters alongside Hale, under the pretense that Mason was out of town. The series ended in 1995.

Mason stories haven’t been confined to TV. The character and his cast have appeared in comic books and were featured in a newspaper strip from 1950 to 1952. The Colonial Radio Theater on the Air started adapting Mason novels into full-cast audio dramas in 2008. For decades, the Burr series has been a staple of syndication and has been widely available on DVD. When the streaming age began, the show found new interest; the first seven seasons currently stream on CBS All Access.

The trailer for HBO’s Perry Mason. (Uploaded to YouTube by HBO)

That brings us to today, and the all-new version hitting HBO. The new series boasts all-star producers, including Team Downey (the production company of Robert Downey Jr. and his wife Susan), and Rolin Jones and Ron Fitzgerald, who are known for Friday Night Lights and other programs. The show is set in 1932, the year before the first novel was released. Matthew Rhys (The Americans) stars as Mason, while Chris Chalk plays Paul Drake and Juliet Rylance is the new Della Street. Breaking convention, the episodes are listed by chapter titles (“Chapter One,” for example), rather than “The Case of . . .” The handful of critics who have filed reviews, including Dan Fienberg from The Hollywood Reporter, Judy Berman from Time, and Alan Sepinwall from Rolling Stone, have given high praise to the cast and the look of the show. It remains to be seen if America will embrace this new Perry Mason. Based on nearly a century’s worth of evidence, it’s probably safe to bet on a favorable verdict.

Featured image: Raymond Burr as Perry Mason from the 1961 CBS series (Cowles Communications, Inc.; photograph by Robert Vose / Public domain)

The 40 Greatest Animated TV Series Theme Songs

Read The 50 Greatest TV Theme Songs of All Time: Live-Action

Read The 25 Greatest TV Themes of All Time Part 2: Spoken-Word

Bring on the cartoons! In honor of the late, great Casey Kasem, who voiced many a classic cartoon character, including both Shaggy from Scooby-Doo and Robin on Super Friends, this is going to be a Top 40. So, what constitutes the greatest animated TV theme song? Sometimes it’s a shockingly great instrumental. Sometimes it’s something that elegantly explains the premise for the show and sets up the action. And sometimes it’s just wacky.

Let’s grab a bowl of cereal, plunk down in front of the tube, and count down the best from Saturday mornings and after school.

40 (tie). Mobile Suit Gundam Wing (1995-1996) and Cowboy Bebop (1997-1998)

(Uploaded to YouTube by crunchyrollcollection)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Funimation)

Mobile Suit Gundam Wing is part of the mighty Gundam franchise; the giant robot pioneer hit screens in 1979 and is still going strong. Gundam Wing is one of the series that stepped outside of the main Gundam continuity to tell its own story of rebellion and the cost of war. The J-pop theme “Just Communication” by pop duo Two-Mix is by turns propulsive and introspective, which are the two dominant moods of the series. Two-Mix also did the main song “White Reflection” for the wrap-up film, Mobile Suit Gundam Wing: Endless Waltz.

Cowboy Bebop is frequently held up as one of the great anime series. A kicky space noir, the show serves up deft characterization, swift action, and a knockout punch of a conclusion. The jazzy theme is called “Tank!” and it invokes the two-fisted P.I. tales that the show emulates.

39. Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995-1996)

If you’ll allow a personal digression, Neon Genesis Evangelion is this writer’s favorite anime, period. A cryptic rumination on religion, depression, grief, and the possible futility of love that plays out against the seemingly hopeless series of battles of giant robots and their teen pilots against increasingly monstrous creatures that might in fact be angels, EVA (as its fans call it) is so incredibly popular that its creator has been doing a new rebooted edition for the past several years. The original theme, “A Cruel Angel’s Thesis” starts off like soft rock, then gets increasingly frenetic.

38. Family Guy (1999-are you kidding? It’s still going?)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Dungeon Dogs)

Somewhere in his insane heart, Seth MacFarlane is just a song and dance man. That’s evident in the opening to his most famous creation, Family Guy. Starting off as both a parody and tribute to All in the Family with Lois and Peter at the piano, it evolves into a Broadway-style showstopper. Well done, Captain Mercer.

37. The Smurfs (1981-1989)

(Uploaded to YouTube by smoulinka189)

Apologies in advance: just by mentioning The Smurfs theme, it’s already stuck in your head. Obviously a measure of greatness.

36. Alvin and the Chipmunks (1983-1990)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Argo 4017)

Alvin, Simon, and Theodore have had several animated series since Ross Bagdasarian brought them to life in 1958. And while the current Nick series ALVINNN!!! And the Chipmunks has been running since 2015, the longest-running and most popular was the ’80s iteration. The of-the-moment pop sound acknowledges in the lyrics that it had “been a while” since they’ve been on TV, but the bright and fun intro demonstrates that they are back to stay.

35. The Simpsons (December, 1989-the end of time, apparently)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Steven Brandt)

Danny Elfman broke big in music as the founder and leader of Oingo Boingo, then transitioned to a long and successful career as a composer for such films as Batman, Beetlejuice, Spider-Man, and Avengers: Age of Ultron. But the theme that’s probably heard the most is his main title for The Simpsons. At 679 episodes and counting, it’s one of the most-played themes in prime-time TV history, let alone animation.

34. Popeye (1933-present)

(Uploaded to YouTube by narutofighter99)

“I’m Popeye the Sailor Man” was composed in 1933 by Sammy Lerner for the first Max Fleischer Popeye theatrical cartoon. The song has been used in some fashion for every iteration of the character since, including the jump to original TV productions in 1960. And no, he does not say that he lives in a garbage can.

33. Darkwing Duck (1991-1995)

(Uploaded to YouTube by jm3dina)

“I am the terror that flaps in the night!” Darkwing Duck was an extremely popular series from Disney that debuted in the wake of the “Batmania” that followed the 1989 Batman film. A parody of The Shadow, Batman, and other classic heroes, Darkwing Duck routinely fights a rogues’ gallery of bizarre enemies while trying to raise his adopted daughter. The jazzy score fits squarely in the animated-noir-hero subgenre, and is sprinkled with the titular mallard’s catchphrases, like “Let’s get dangerous.”

32. Avengers: Earth’s Mightiest Heroes (2010-2013)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Themecstacy)

If you’re looking for the best adaptation of the Avengers outside of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, it’s right here. Produced during the run-up to and just after the first film, Avengers: Earth’s Mightiest Heroes mines the rich legacy of comic book stories in a way that’s even more faithful to the books in many places than the movies. Chicago band Bad City performs the rocking opening theme, “Fight as One,” which articulates the notion of pulling together for a battle; it even includes a shout of “Avengers Assemble!”

31. Heathcliff (1984-1985)

(Uploaded to YouTube by BenW873a)

Another character that’s had plenty of shows, the comic strip cat got the added bonus of frequently being voiced by vocal genius Mel Blanc. The series has some great animation and a fun theme song by legendary composers and producers Haim Saban and Shuki Levy. The vocals to the poppy throwback are by Noam Kaniel, who you’ll see hanging out with some mighty mutants later on.

30. The Tick (1994-1996)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Macka8)

Doug Katsaros wrote the whacked-out jazz-inspired theme for super-hero parody The Tick. Featuring the slightly dim, but nigh-invulnerable do-gooder of the comics, the show follows the adventures of the Tick, his moth-costumed accountant sidekick Arthur, and their various super-hero allies as they battle incredibly strange threats, including one gangster that has a chair for a head.

29. Spongebob Squarepants (1999-present)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Nick Animation)

Let’s just put it this way. “Who lives in a pineapple under the sea?”

You know you just answered out loud.

28. Teen Titans (2003-2006)

(Uploaded to YouTube by AnakinSkywalker31)

DC Comics debuted the Teen Titans in the 1960s as a team composed of the sidekicks of prominent Justice Leaguers and led by Robin, the Boy Wonder. The comic relaunched in the early 1980s under writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Perez; Wolfman and Perez combined classic characters with new creations and the book became a massive success. The animated series features Robin, Beast Boy, and three Wolfman-Perez creations: Cyborg, Starfire, and Raven. The J-pop theme comes from Puffy AmiYumi, and it was so popular that the band got their own show in the States for a while.

27. Inspector Gadget (1983-1986)

(Uploaded to YouTube by 5020maine)

Inspector Gadget sits squarely in the center of old-school gumshoe and science-fiction. The lead is a detective (voiced by none other than Don Adams of Get Smart) that is also a cyborg, capable of sprouting springing legs and helicopter rotors from his head when the need arises. The Saban-Levy theme song juggles inspiration from Henry Mancini and Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King” and is known for its repetition of the lead’s name and the refrain of “Go, Gadget, Go!”

26. Speed Racer (1967-present in various incarnations)

(Uploaded to YouTube by superherocartoonsite)

Here’s a huge asterisk. Yes, this is an anime import. However, the theme was completely redone and rewritten with English lyrics, resulting in one of the most well-known songs from an animated production. The 1967 take saw Peter Fernandez (one of the American producers and voice-actors) put together a new arrangement of Nobuyoshi Koshibe’s original with new lyrics; the song is performed by Danny Davis and the Nashville Brass.

25.Hong Kong Phooey (1974-1976)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Derek S)

Hong Kong Phooey is a Hanna-Barbera series capitalizing on the martial arts fad of the early ’70s, making its debut in the same month that Carl Douglas’s “Kung Fu Fighting” was on the charts. The lead character is voiced by Scatman Crothers, who also sings the theme. Hanna and Barbera wrote the song themselves with their longtime musical director Hoyt Curtin.

24. George of the Jungle (1967)

(Uploaded to YouTube by ShortNew)

Though short-lived on its original run, this show from Jay Ward and Bill Scott (creators of Rocky and Bullwinkle) consists of three segments, two of which make this list. In the cartoon pantheon, George is probably most famous for his theme, which contains everything you need to know about the show.

23. Super Chicken (1967)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Ipostcartoons)

The other two segments on George of the Jungle are racing cartoon Tom Slick and this classic super-hero send-up. Henry Cabot Henhouse III drinks his super-sauce and becomes . . . Super Chicken! The show’s most beloved quote, “You knew the job was dangerous when you took it,” does indeed make it into the lyrics.

22. Mighty Mouse (1955-1967)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Gynmusic)

Originally called “Super Mouse” in his 1942 debut, the heroic rodent was renamed and redesigned with his familiar red and yellow costume in 1944. Though several theatrical shorts were made, the character didn’t really get mass popularity until it shifted to TV. The theme by Marshall Barer is perhaps most recognizable for the line, “Here I come to save the day!” It was also put to memorable use in an early Saturday Night Live bit by Andy Kaufman.

21. Underdog (1964-1973)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Robert Gordon)

One of the longest-lasting Superman parodies, Underdog features the canine superhero battling villains like mad scientist Simon Bar Sinister and often rescuing his reporter love interest Polly Purebred.

20. Duck Tales (1987-1990; 2017-present)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Dassenman)

The much-loved Duck Tales puts Donald Duck’s Uncle Scrooge McDuck and his nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie together for a wide-ranging series of adventures. Inspired by the classic comic books by Carl Barks, the show regularly introduces villains and supporting characters from the comics and, via Scrooge’s pilot Launchpad McQuack, sets up the unofficial spin-off Darkwing Duck. The show was rebooted in 2017, but kept the original theme song, albeit in a new version.

19. Pinky and The Brain (1996-1998)

(Uploaded to YouTube by cartoonintro)

This spin-off of Animaniacs features the popular titular lab mice. Brain is an evil genius, and Pinky his significantly less-intelligent assistant. A number of lines from the show became pop culture catchphrases, but the most famous is the regular exchange, “What are we going to do tonight, Brain?” “The same thing we do every night, Pinky. Try to take over the world!”

18. X-Men (1992-1997)

(Uploaded to YouTube by jm3dina)

Bonus: Japanese theme songs

(Uploaded to YouTube by Gordonlen)

Originally seen as sort of middle children from the initial burst of creativity that was Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s vision of the Marvel Universe, the X-Men were rebooted into an international team in 1975 and rose to become Marvel’s most popular book. 1980’s “The Dark Phoenix Saga” and its aftermath firmly implanted Uncanny X-Men as the best-selling regular comic of that decade. When a new spin-off (simply titled X-Men) was launched in 1991, the first issue sold over eight million copies. The animated series launched in its aftermath and became an immediate hit, paving the way for the film franchise. The propulsive theme song is a genre classic, combining elements of spy and science-fiction themes of the past. As a bonus, we’re including the two opening sequences that were made for the Japanese release of the show; they rock in their own right.

17. The Bugs Bunny Show; The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Hour and iterations (1960-1983)

(Uploaded to YouTube by PizzaGuy2002)

In 1960, the Looney Tunes stable came to TV with an anthology format that pulled from theatrical shorts stretching back to 1948. Over the years, the show would switch formats, titles, timeslots, and networks, but the opening theme “This Is It!” would remain a constant until it was abandoned in 1984. The song combines a sort of Vaudeville sensibility while presenting the main cast; the opening also includes a snippet of another theme that lies ahead in the countdown.

16. The Jetsons (1962-1963)

(Uploaded to YouTube by WarnerArchive)

In terms of lyrics, you can’t get simpler than Hoyt Curtin’s The Jetsons theme. The song simply introduces George Jetson, his boy Elroy, daughter Judy, and Jane, his wife. Originally shown in prime-time on ABC, it was the first series broadcast in color (stablemates The Flintstones were made in color, but only shown in black and white for the first two seasons).

15. Tiny Toon Adventures (1990-1992)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Ridvan Seker)

The first of several series co-produced by Warner Bros. Animation and Steven Spielberg’s Amblin’ Entertainment, Tiny Toon Adventures opened the door for Animaniacs and Pinky and the Brain, among others. The approach is that the original Looney Tunes characters are teaching a whole new class of young cartoon characters at Acme Looniversity in Acme Acres. Most of the big name characters have young analogues like Babs and Buster Bunny, Plucky Duck, Hampton (a pig like Porky), Dizzy Devil, Montana Max (a young, rich Yosemite Sam type) and so on. The exposition-heavy theme comes from famed composer Bruce Broughton, who’s won 9 Emmys and scored countless TV shows and films.

14. Super Friends (1973-1986)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Tommy Retro’s Blast from the Past!)

Though there are spoken-word narration bits that vary from season to season, the main Super Friends theme stuck around (with minor changes here and there) for 13 years. It was another stellar piece from our old friend, Hoyt Curtin. In the late 1990s, the theme was remixed by Michael Kohler for a Cartoon Network promo called “That Time is Now!”

13. Freakazoid (1995-1997)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Media Graveyard)

Cut from the same cloth as the theme to The Tick, the boppy and jazzy Freakazoid theme is filled with explanations of the show’s premise paired with oddball non sequiturs. That pairs perfectly with the frequently-distracted, internet-powered hero.

12. Pink Panther (1963-present)

(Uploaded to YouTube by ThievingMoney)

Why is this a classic? Because you heard it in your head the second you read the name. The creation of the Pink Panther has a strange genesis. The Pink Panther was originally a diamond in the Inspector Clouseau series of films, so named because the diamond contained the image of a panther if held up to the light. Beginning with the second film (The Pink Panther), the credits were animated, with the diamond panther becoming the familiar character. The animated panther then spun-off into theatrical shorts and various animated series on TV. In every iteration, it’s kept the Henry Mancini tune from the movies.

11. Road Runner

(Uploaded to YouTube by colonelgreenn)

As part of the The Bugs Bunny Show and later its own separate program, the Road Runner comes equipped with a quirky, bouncy, slight countrified tune that details the eternal struggle between Wile E. Coyote (Overconfidentii vulgaris) and the Road Runner (Disappearialis quickius). The Chuck Jones shorts are remembered for the Coyote’s reliance on ACME devices and the continual beating he takes in trying to catch his prey.

10. Josie and the Pussycats (1970-1971)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Off-Ramp to Nowhere)

Everybody’s favorite feline-inspired band sprung from the pages of Archie comics to the screen in 1970. The adaptation was actually driven by the fact that The Archie Show cartoon of the late 1960s delivered a hit single in the form of “Sugar Sugar,” and the producers wanted to see if they could pull it off again with other Archie Comics characters. Though no Top Ten hits resulted, a couple of important things came from the show, aside from its excellent theme song. One is that Valerie, voiced by Patrice Holloway, was the first black female character in Saturday morning cartoons. The other is that it was the first significant Hollywood job for the speaking and singing voice of Melody, Cherie Moore; you’d know her better as Cheryl Ladd of Charlie’s Angels.

9. Jem (aka Jem & The Holograms, 1985-1988)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Hasbro)

In the 1980s, Hasbro caught lightning in a bottle twice in a three-partner collaboration with Sunbow Productions and Marvel Productions. The partnership resulted in huge hit comics, toys, and TV shows with G.I. Joe and The Transformers. Turning their attention to the girls’ market, Hasbro launched a doll line with a tie-in show that featured a female band that was led by an enigmatic figure with a secret identity. That was Jem, whose singing parts were performed by Britta Phillips of the acclaimed dream pop band Luna. Though the toys weren’t a huge hit, the show was, and was the # 3 show among kids in 1987. Overall, 151 different songs were created during the tenure of the show.

8. Animaniacs (1993-1998)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Max Demski)

Part of the WB/Spielberg deal, Animaniacs was the anthology show that introduced Pinky and the Brain as regulars. The main segments featured Yakko and Wakko, “the Warner Brothers and the Warner sister, Dot.” The three leads would wreak giddy havoc over a number of pop culture institutions, memorably destroying a Barney lookalike and sneaking an incredibly inappropriate Prince joke past the censors. Some of the songs from the show are still used in classrooms, like “Nations of the World” (23 million views on YouTube) and “Wakko’s 50 State Capitols.” The Emmy-winning main theme explains the plot, and has a number of variations with sight gags for the penultimate line; as they rhyme with “totally insaney,” different versions have the characters singing everything from “here’s the show’s namey” to “Citizen Kaney” to “Dana Delaney.”

7. ThunderCats (1985-1989)

(Uploaded to YouTube by leopard9751)

Rankin/Bass may be most known for their awesome array of holiday specials, but they’re also the production team behind one of the best cartoons of the 1980s, ThunderCats. The series was developed and co-written by comic book artist Leonard Starr and writer Stephen Perry. They gave the show a rich fantasy and science-fiction background and packed the series with action. Throughout the decade, Rankin/Bass developed two other shows with similar approaches, Silverhawks and TigerSharks. When ThunderCats was rebooted in 2011, the show explicitly tied new versions of the other two sets of characters into a shared continuity.

6. G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero (1983-1986)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Hasbro)

Hasbro developed the original 12-inch G.I. Joe action figures in the 1960s. America’s Fighting Man had a dip in popularity after Vietnam and shrunk to the 8-inch scale for a bit. In 1982, the figure was reborn as a whole team in the Stars Wars 3-3/4” scale; the unique personalities (and Cobra villains) were created by comic writer Larry Hama in a cooperative deal with Marvel that saw Hasbro finance animated commercials for the new comics. It was only a matter of time before the new toys and comics became a TV series, and it arrived with the instantly recognizable theme that incorporates the line’s subtitle: A Real American Hero.

5. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1987-1996)

(Uploaded to YouTube by EKhan33)

In comics in the early 1980s, the two biggest crazes were mutants (see, X-Men) and ninjas (by way of Frank Miller’s run on Daredevil). Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird parodied the concepts with their black and white indie comic Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and a cult hit was born. The cartoon lightens up the darker comic quite a bit; the lighter tone is set by the theme, which was composed by D.C. Brown and Chuck Lorre (who would go on to create Two and Half Men and The Big Bang Theory, among others).

4. The Flintstones (1960-1966)

(Uploaded to YouTube by Andre Aleksandruk)

The Flintstones holds the distinction of being the first animated series to be broadcast in prime time. The Hanna-Barbera sitcom draws inspiration from The Honeymooners, but combines domestic comedy with an immersive world filled with Stone Age and dinosaur puns. You won’t be surprised that Hoyt Curtin wrote the theme; you might be surprised to discover that the first two seasons had a totally different theme and that “Meet the Flintstones” didn’t become the theme until Season 3. The original theme was called “Rise and Shine,” but it’s been replaced in rebroadcast for decades with the more familiar “Meet the Flintstones,” which is, of course, the entry here. By the way, the line after “Let’s ride/with the family down the street” is “Through the/courtesy of Fred’s two feet.”

3. The Transformers (1984-1987)

(Uploaded to YouTube by MakAnt88)

Following up their massive success with G.I. Joe, Hasbro, Sunbow, and Marvel again collaborated on a new Hasbro acquisition. Hasbro had bought the rights to a number of disconnected toy lines, all of which had the common denominator of being robots that transformed into cars, planes, and more. Marvel writer Bob Budiansky took the Larry Hama role and fleshed out names and backstories for the characters, based on Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter’s idea to break the bots into Autobots (good guys) and Decepticons (bad guys). Every piece of the franchise was a huge hit. The Ford Kinder-Anne Bryant theme combines the two marketing taglines for the toys “More than meets the eye” and “Robots in disguise” into lyrics. Since that time, the Transformers have appeared in a number of TV series, films, and constantly reinvented toy lines; the theme has also been repurposed and covered a number of times, including Lion’s version for the animated Transformers: The Movie and Cheap Trick’s take for the live-action Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen.

2. Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! (1969-today in various incarnations)

(Uploaded to YouTube by TITRO99)

Last year, the Post covered the long history of Scooby and the gang. While there have been a few different themes with different iterations of the show, the original “Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!” theme is the most well-known and the one that keeps coming back. A classic premise-setting tune, the song gives you the basic gist of the plots that revolves around Mystery Incorporated. The theme was composed by David Mook and Ben Raleigh. When the popular direct-to-video Scooby movies began in the late 1990s, a number of high-profile musical acts recorded versions for different films, including The B-52s, Third Eye Blind, and MxPx.

1. Spider-Man (1967-1970)

(Uploaded to YouTube by omimon)

Commonly referred to as the “Ralph Bakshi Spider-Man cartoon,” even though the storied animator didn’t take over as Executive Producer and Animation Director until Season 2, Spider-Man took off based on its use of villains and plots from the comics and its devotion to the trippy visual stylings of Spider-Man co-creator and original artist Steve Ditko. Spider-Man’s other dad, Stan Lee, was a consultant on the show, as was John Romita Sr., who was drawing the comics by that time. The much-loved theme song was written by lyricist Paul Francis Webster (who was nominated for 16 Best Song Oscars, winning three) and composer Bob Harris. The song is so pervasive in pop culture that people that have never even seen the 1960s cartoon know it. Iterations and samples of it are still used in the Spider-Man franchise today. An orchestral version of it even replaces the Marvel Studios fanfare in the openings of both Spider-Man: Homecoming and Spider-Man: Far from Home.

Featured image: Shutterstock

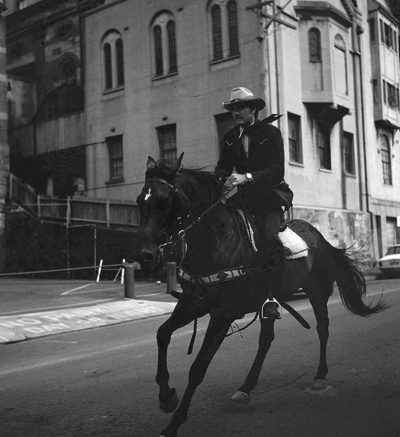

Justified: 10 Reasons You Should Watch This 10-Year-Old Show

We live in the age of “Peak TV” — shows of cinematic quality that consistently elevate the medium while expanding what’s possible in terms of storytelling. Tucked in among those programs is Justified, which hit screens 10 years ago this month for a six-season run that pulled in eight Emmy nominations and two wins. Despite its acclaim, Justified remains an underrated underdog, a frequently overlooked gem of Peak TV. Here are 10 reasons why you should be watching this 10-year-old show.

1. Elmore Leonard

Justified is based on the work of beloved crime and Western writer Elmore Leonard. Already a legendary presence by the 1990s for his gritty tales of crime and hardened (and frequently, not that bright) criminals, he experienced a renaissance of sorts as a number of his books were adapted into high-profile film successes, including Out of Sight, Get Shorty, and Jackie Brown (based on Rum Punch). Among the TV films based on his work is 1997’s Pronto, which is Leonard’s first story featuring Deputy U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens. Givens also appears in Riding the Rap and the short story “Fire in the Hole,” a tale that would provide the basis for Justified’s pilot episode.

2. Graham Yost

Screenwriter Yost started out in television before making the leap to film as the original writer of Speed. He spent much of the ’90s on huge action vehicles like Broken Arrow and Hard Rain. He later worked with Tom Hanks on the mini-series From the Earth to the Moon and The Pacific and created the acclaimed, but short-lived, TV series Boomtown. Yost developed Justified for FX; originally titled Lawman, the show got its initial 13-episode order in the summer of 2009. The title changed to “Justified” in part because the inciting action of the series is a controversial, but legally justified, shooting that occurs when Givens faces down a hitman in Miami.

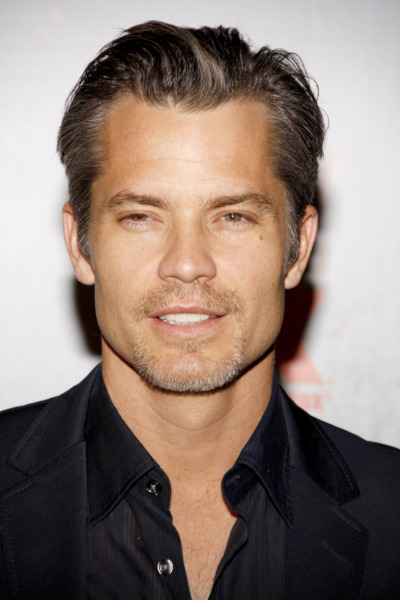

3. Timothy Olyphant

When you star in one classic Western TV series as a lawman in a hat, the project needs to be something special to lure you back. Timothy Olyphant had already made a name playing sketchy characters in film before landing in the center of a world-class ensemble on HBO’s Deadwood. As such, the role of a quick-witted, quick-drawing lawman fueled by dueling cores of anger and decency fit Olyphant like his cowboy hat; The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum called him “perfectly cast.”

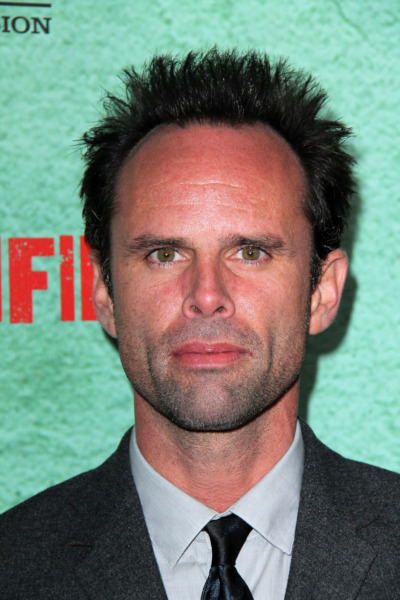

4. Walton Goggins

A perfectly cast hero needs a perfectly cast antagonist, and wow, did Justified get that. Rising from a “who was that guy?” character actor to being one of the best things about award-magnet shows like The Shield, Sons of Anarchy, Vice Principals, and The Righteous Gemstones while stealing scenes in films as diverse as Django Unchained and Ant-Man and the Wasp, Walton Goggins commands attention every time he’s on screen. His Boyd Crowder is by turns charming and deceptive, hilarious and lethal. He’s the kind of villain with so much life and complexity that you want him to stay alive. Every scene with Olyphant and Goggins is electric, whether its trading funny dialogue, fighting each other, or occasionally teaming up to stay alive. Tim Goodman wrote for The Hollywood Reporter that “Raylan and Boyd will certainly take their place with the best of any of the characters from those other shows” (and by “those other shows,” he enumerated The Sopranos, The Wire, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad).

5. The Writers and Directors