Considering History: Voter Suppression and Racial Terrorism, the Twin Pillars of White Supremacy

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

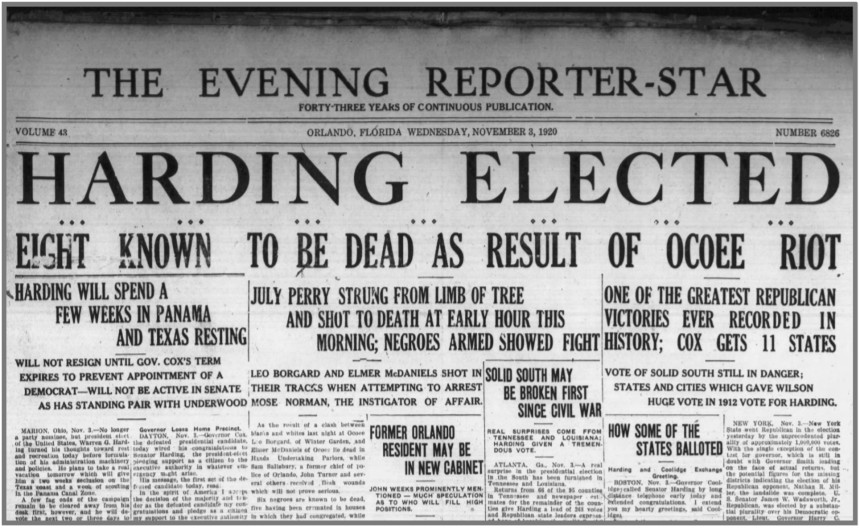

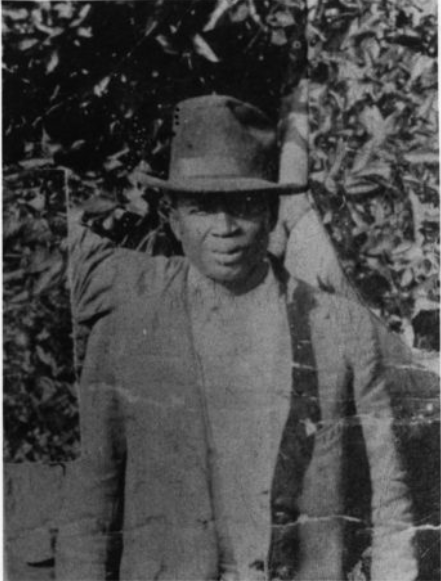

On November 2, 1920, as voters across the country went to the polls to decide a presidential election between two Ohio politicians, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding and Democratic Governor James M. Cox, violence erupted in the Florida town of Ocoee. Local African-American farmer Mose Norman tried to exercise his Constitutional right to vote, and was turned away twice under the pretense of the state’s Jim Crow efforts to disenfranchise black voters. An angry white mob then pursued Norman, laying siege to the home of another man, Julius “July” Perry. Perry fired on the attackers in self-defense, and the mob seized upon that action to terrorize the town’s Black community, eventually killing Perry and more than fifty other African-American residents, burning down homes and businesses, and forcing much of the rest of the community to flee the town.

The Ocoee massacre, known as the “single bloodiest day in modern American political history,” had its roots in multiple historical trends. Like states throughout the Jim Crow South, Florida had developed in the 50 years since the 15th Amendment’s ratification numerous legal measures and social practices intended to make it impossible for African Americans to vote. But those longstanding voter suppression measures were complemented by a much more immediate, violent threat of force: the day before the election, members of the newly resurgent, 2nd Ku Klux Klan had marched through Ocoee, proclaiming through megaphones that “not a single Negro will be permitted to vote.” And no 1920 act of racial terrorism can be separated from the prior year’s epidemic of such violence, the year-long series of lynchings and massacres that came to be called the “Red Summer of 1919.”

Those factors help us understand the divisions and discriminations at the heart of American culture in 1920. But on the 100th anniversary of the Ocoee massacre, and as we approach another election day, that specific historical event can also help us to better recognize an overarching, profoundly relevant American trend: the way in which voter suppression has consistently gone hand in hand with racial terrorism to prop up white supremacy.

In recent years, we’ve started to do a better job of remembering the history of white supremacist racial terrorism in America through such vehicles as public memorials and pop culture texts, including horrific individual events such as the 1921 Tulsa massacre and the century-long lynching epidemic. But too often the stunning brutality and destruction of those acts of violence can make them seem like impromptu explosions, perhaps reflecting consistent undercurrents of racism but not the result of purposeful, extensive, organized political planning.

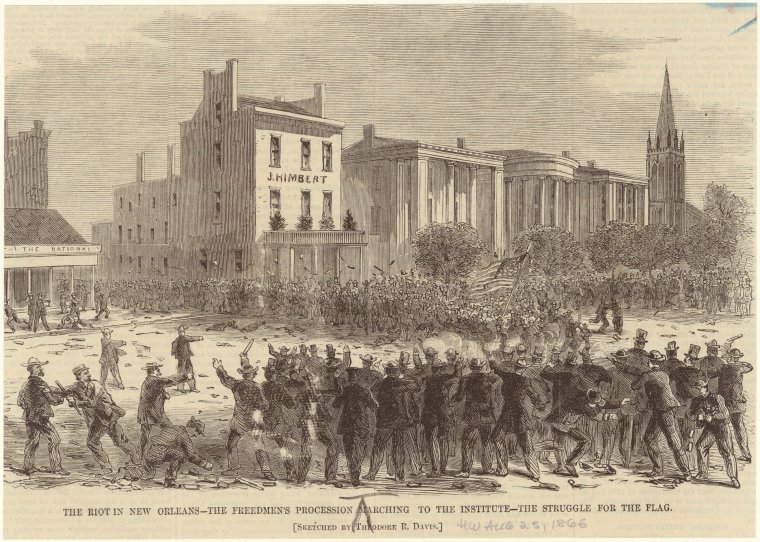

Yet the truth is that these acts of racial terrorism have consistently been tied to planned, organized, systematic plans for voter suppression and related political agendas, as illustrated by not just Ocoee in 1920, but also three prominent 19th century massacres and one from the Civil Rights era. The July 30, 1866 New Orleans massacre began when white supremacists attacked 130 African-American residents marching toward the Louisiana Constitutional Convention at Mechanics’ Institute; the state legislature had passed a series of Black Codes barring Black men from voting (among many other discriminatory effects), and the marchers were hoping to join the Convention to advocate for their rights. New Orleans’ newly re-elected Confederate mayor, John T. Monroe, led a group of ex-Confederates, police officers, and other white supremacists to attack the marchers, starting a massacre that would end with more than 200 African-American Union Army veterans and another 200+ Black civilians killed.

Despite such racial terrorism, African Americans continued to exercise their Constitutional right and active patriotic goal of voting, and were consistently met with extensive suppression and violence. On November 3, 1874, African-American voters at the polls in Eufaula and Spring Hill, towns in Alabama’s Barbour County, were attacked by members of the widespread white supremacist organization The White League; seven African Americans were killed and another 70 wounded. The Barbour County massacre was one of many such events throughout the South on that 1874 election day, a planned campaign of voter suppression and violence after which League-affiliated officials also threw out legitimate votes for Republican candidates and helped install sympathetic Democratic officials in their place (a shift often defined as the beginning of the end of Federal Reconstruction).

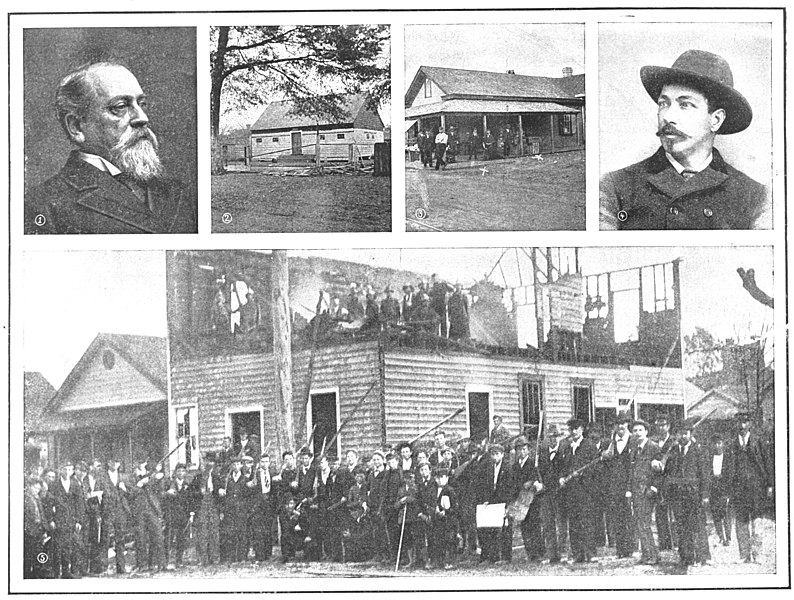

The November 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) coup and massacre originated from even more overtly organized voter suppression goals. By late 1898 Wilmington was one of the last communities in North Carolina (and the entire Jim Crow South) not governed by white supremacists — the so-called “Fusion” Party, featuring African-American political figures and their Republican and Populist white allies, had in the 1896 election held on to many of the city’s positions. White supremacists targeted the next election day, November 8, 1898, as an occasion to reverse that trend by force and violence: planning for months an extensive program of both voter suppression and systemic violence, alongside an accompanying propaganda campaign in the media, that resulted in both a coup d’etat and a massacre that devastated the city’s African-American community.

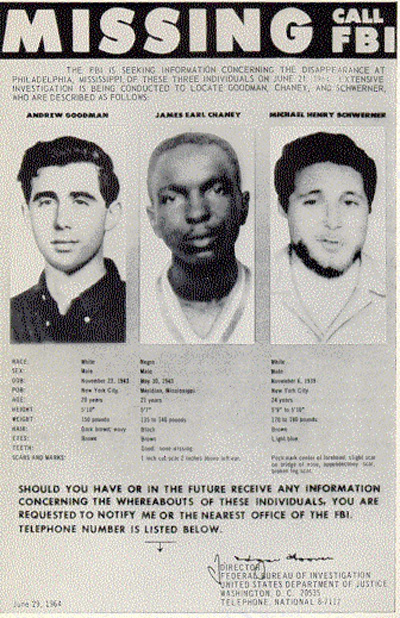

One of the latest documented lynchings, the infamous June 1964 murder of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner near Philadelphia, Mississippi, was similarly interconnected with voter suppression. The three men were working for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as part of its Freedom Summer campaign to register African-American voters in Mississippi and throughout the South, and were on their way to a registration event at a local church when they were pulled over by local law enforcement. An extensive FBI investigation determined that members of the Philadelphia Police Department, the Neshoba county sheriff’s office, and the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan subsequently abducted and killed the men. The collaboration between those official and domestic terrorist organizations doesn’t simply reflect their overlapping membership; it also illustrates that the murder of these voting rights activists was part of a political campaign to suppress African-American votes and keep these white supremacist forces in power.

Throughout American history, those who have fought for the right to vote have had to do so in direct opposition to some of the nation’s most powerful forces, including white supremacist suppression and violence. Those battles continue into the 21st century, and as we continue to fight for and to exercise the right to vote, it’s vital that we remember the foundational and consistent ties between voter suppression and white supremacist racial terrorism.

Featured image: The New Orleans Massacre (Artwork by Theodore R. Davis for Harpers Weekly / Wikimedia Commons)

The Campaign That Sold the Klan

It was one of the greatest — and most disturbing — success stories of the 1920s. In just five years, the Ku Klux Klan grew its membership from a few thousand to five million. What had been an organization principally of rural white southerners in the 1860s now included among its members doctors, lawyers, and professors in both northern and southern states. How did they do it? Like any modern organization: they launched a marketing campaign.

The Klan had begun as a fraternal order of former Confederate soldiers who terrorized freed slaves and members of the state governments implementing Reconstruction. But when Reconstruction was dismantled, the Klan melted away.

By 1915, the Klan had just one member: William Joseph Simmons. He was inspired to revive the organization after watching D. W. Griffith’s film, Birth of a Nation, which portrayed Klansmen as heroes.

To Simmons, 1915 seemed right for the Klan’s return. Many southerners were angered by progressive policies that were expanding the federal government and supporting civil rights for minorities. Also, many resented the flood of immigrants and feared foreign cultures would destroy what they considered “traditional American values.”

Simmons felt the country would be receptive to an organization pledged to white nationalism. On Thanksgiving Eve, 1915, atop Stone Mountain near Atlanta, Simmons swore 15 candidates into the revived Klan. After they repeated the oath, he set a large cross on fire. It was a bit of stagecraft dreamed up from Birth of a Nation that had captivated Simmons, and it soon became a Klan tradition.

But something was missing. Recruitment was slow. In five years, Simmons had added only 5,000 members.

Then he met Mary Tyler and Edward Clarke, professional fundraisers who saw potential in the Klan, particularly when Simmons offered them 80 percent of the profits from dues. In June 1920, they became the brains behind the Klan’s national marketing campaign.

The timing for a racist organization was better than it had been five years earlier. There was a new defiance among black Army veterans, now returning to the South from the war. Having served their country, they were unwilling to reprise any subservient role in their communities. Major race riots had already erupted in several cities.

But Clarke and Tyler realized that racism wasn’t enough. Not every part of America was as interested in suppressing black Americans and protecting white power. The Klan couldn’t grow unless it reached a broader audience.

So Clarke and Tyler divided the country in eight regions and sent out 1,000 agents to identify the focus of bigotry and fear in their assigned areas: labor-union organizers and communists in the industrial north, Asians on the west coast, Jews and Catholics almost anywhere.

They began to expand the Klan’s mission, stirring hatred against these groups.

The two also tapped into Americans’ anger at accelerated social change. They wanted to channel the disapproval of the media that mocked tradition, the rebellious attitude of young people, the immodest behavior of women, and, of course, jazz.

Having relatively few adherents in cities, the Klan adopted several attitudes popular in rural areas. They helped enforce Prohibition and they denounced motion pictures.

Almost everywhere they found a public yearning for a golden past, where they remembered an America free of foreign influences. Millions were drawn to the Klan’s policy of “America for Americans” as well as its sometimes violent enforcement of fundamentalist Protestant values.

Many members would never have supported the beatings, tar-and-featherings, murders, and kidnappings committed by other Klansmen. They believed in the Klan was a patriotic, God-fearing organization that revered traditional values. To them, it was simply a fraternal organization, a good place to enjoy white privilege, and maybe do some business networking.

Tyler realized that American women were another promising market. “The Klan stands for the things women hold most dear,” she told the New York Times in 1921. She developed a women’s Klan that eventually claimed 500,000 members, who hosted picnics and attended cross burnings.

They launched a modern media campaign for Simmons, lining up interviews with reporters. Suddenly the Klan’s message was reaching whole new parts of the country. Within a few months, membership had grown 2,000 percent.

Meanwhile their agents were recruiting members in every part of the country. About half of every $10 initiation fee they collected was forwarded to the national office in Atlanta, most of it flowing into the pockets of Clarke and Tyler.

In addition, they were getting a kickback on the sale of official white robes, charging $6.50 for robes that had cost them $3.28. Sensing even greater profits, they began churning out various Klan publications for members. As another sideline, they managed real estate on Klan-owned properties. Within a year, Clarke and Tyler had taken in over a million dollars.

It had been an illegal, covert organization in the Reconstruction era. But in 1925, over 50,000 Klansmen marched boldly through Washington D.C. And, contrary to tradition, not a single one wore a mask.

Not only had the Klan gained social acceptance, it held political power. Klan-backed candidates held office in city and state governments across America, where they protected the Klan’s interests. In Indiana, Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson could even claim, with good reason, “I am the law.”

The Klan might have seemed unstoppable, but the end came soon afterward as it was rocked by several scandals. In addition, the fallout from several investigations was bringing to light the true work of the Klan.

The New York World’s investigation revealed that, in 1921, the Klan was responsible for four murders, a mutilation, 41 floggings, 27 tar-and-featherings, five kidnappings, and 43 threats and warnings to leave town. Civic groups started posting the Klan’s membership lists publicly, and the NAACP led a successful public education campaign about the abuses of the Klan.

One of the scandals took down Tyler. She and Clarke were planning to oust Simmons and take over the Klan’s leadership when they were arrested in a “house of ill repute.” Police discovered them conducting an affair despite being married to others — while in possession of bootleg alcohol. Klan members were outraged, especially when they discovered Tyler, a woman, had been the force behind the Klan’s rapid growth.

She was accused of embezzlement and forced out of the Klan in 1922.

That same year, the FBI was requested to investigate the Klan control of northern Louisiana. The complaint said members had already tortured and killed two men who had opposed the organization. The FBI focused its efforts on Clarke, who had been able to remain an officer in the Klan and was now taking $8 out of every $10 initiation fee.

Unable to convict Clarke on any existing law, he was charged with violating the Mann Act when he drove his mistress across a state line. He, too, was forced from the Klan and moved out of the country to avoid prosecution.

The Klan’s membership started declining rapidly, from its peak of five million members in 1925 to 30,000 in 1930. It reached a low of 3,000 in 2015. Recently, Klan membership has started to pick back up again. There’s been no official word on who is handling their marketing.

Featured image: A flyer advertising a Klan event at the Texas State Fair, 1923 (The Portal to Texas History, the University of North Texas)