Scrambling for Troops

This is the second installment of our six-part series on the lead up to Gettysburg. Click here to read part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move.”

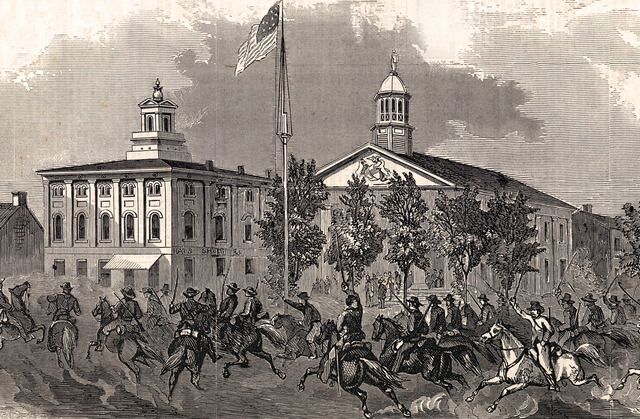

The news reached Philadelphia on a bright June morning in 1863; Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army had invaded Pennsylvania and was heading virtually unopposed to the state capitol. Suddenly, a Post correspondent wrote, the city was filled with a militant spirit.

“One could scarcely turn in any direction without meeting with a fife and drum. Recruiting officers were constantly marching up and down the streets. Large four-horse omnibuses, with bands of music and placards announcing various [assembly points], were driving about the city.

“The apathy, that for a time had seemed to taken possession of the community, was speedily dispelled. The possibility that the rebel horde might reach the Susquehanna, and even cross that stream and destroy our state capitol, was freely entertained yesterday; but there was also a firm resolve, ‘that many a banner should be torn, and many a knight to earth be borne’ before that disgraceful calamity should befall the state.”

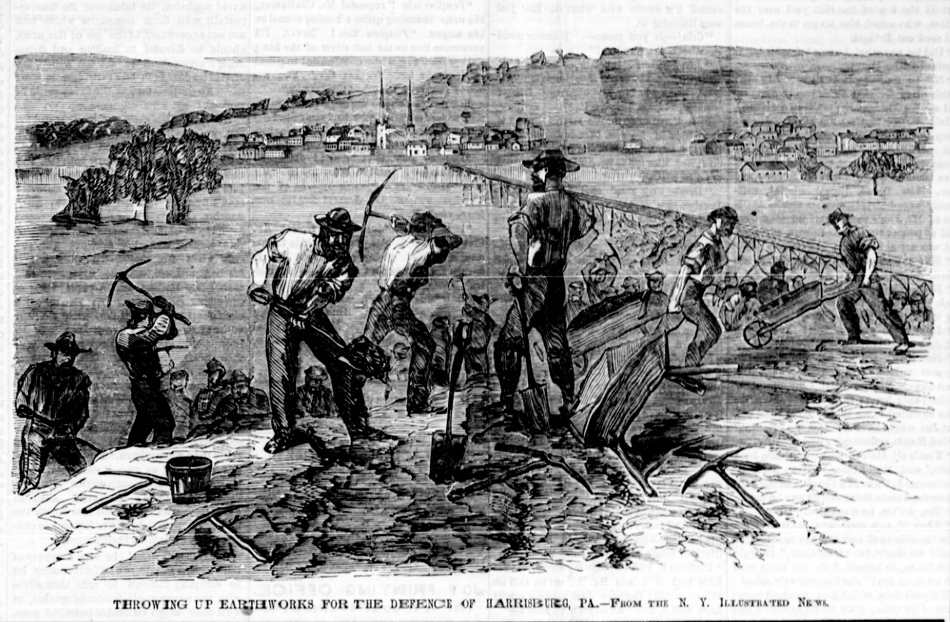

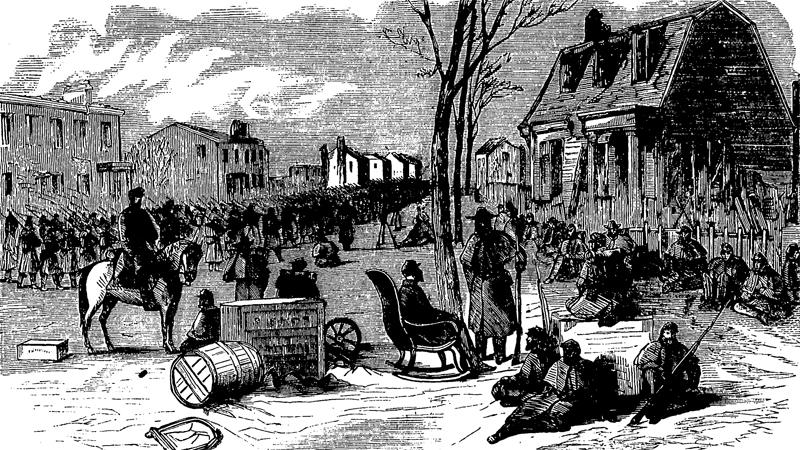

In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania—100 miles closer to the approaching Confederate Army—the mood was quite different. There, residents had panicked after hearing that the rebel army had looted Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Swarms of frantic passengers gathered at the railroad station, desperate to fit into any railway car they could find. The roads out of town were choked with wagons piled high with household effects, bearing families away from the enemy, and the inevitable battle.

The North’s confidence, which ran so high when the war began, was showing signs of collapse. There seemed to be little enthusiasm for fighting. The governor’s call for an emergency militia of 60,000 men was met with only 16,000 volunteers.

The Federal Army was also running low on its supply of soldiers. The eager recruits who had signed up at the war’s beginning were now approaching the end of their two-year enlistment. By the end of the month, more than 30,000 soldiers were due to leave the army. At the same time, enlistments of new recruits were falling behind goals. Men throughout the North were reluctant to sign up with an army that was so often defeated.

Faced with a drastic shortage, Congress passed the unpopular Enrollment Act, which set up the machinery for drafting 300,000 men. The Post editors disliked the idea of this conscription law, particularly its clause that allowed men to hire substitutes or buy exemptions.

Faces of the American Civil War

Photos courtesy The Library of Congress

A man who received a draft notice could hire another man to take his place in the fighting. If the substitute was found acceptable and duly sworn in, the draftee would be free of any obligation to serve, but only, the Post adds, for “the term for which he was drafted.” After the substitute had served the length of service, the original draftee would be again eligible for conscription.

If the draftee couldn’t find a substitute among poor citizens or struggling immigrants, he could simply buy a personal exemption for $300. (Congress set the amount at a level they felt would be affordable to working-class men. When you adjust that figure for 150 years of inflation, it comes close to $6,000 in 2013 money.)

Before the fighting had ended, the War Department had four separate draft calls, which drew the names of 776,000 American men. Few of these men ever saw military service. More than 20 percent never showed up. Another 60 percent were disqualified for physical or mental disability, or because they were the sole support of a motherless child, a widow, or an indigent parent.

Once sworn into service, recruits and draftees were rushed through basic training before being sent to the front. With only minimal instruction and poor leadership, a Post article claimed, it wasn’t surprising that Union troops had been repeatedly outfought by the Confederates. It quoted a Union army officer who had watched the unskilled Yankees at Chancellorsville:

“They have been taught to load and fire as rapidly as possible, three or four times a minute … they go into the business with all fury, every man vying with his neighbor as to the number of cartridges he can ram into his piece and spit out of it! The smoke arises in a minute or two so you can see nothing or where to aim. The trees in the vicinity suffer sorely, and the clouds a good deal. By-and-by, the guns get heated and won’t go off, and the cartridges begin to give out.

“Meanwhile, the enemy, lying quietly a hundred or two yards in front, crouching on the ground or behind trees … rise and advance upon us with one of their unearthly yells, as they see our fire slackens. Our boys, finding that the enemy has survived such an avalanche of fire we have as we have rolled upon them, conclude that he must be invincible, and, pretty much out of ammunition, retire.

The editors urged the army to abandon the practice of forcing men to load and fire in unison. “Accurate loading, and slow firing, at will, and only when the soldiers has an idea that his ball will tell, will do more execution than hasty loading, and rapid firing at something or nothing.”

It was well-intended advice, but would have been useless during the intense fighting at Gettysburg, where soldiers found themselves loading and firing “as rapidly as possible” simply to hold their ground.

By June 28, Lee learned the Union Army had pursued him across 120 miles in 10 days—a remarkable feat of marching at a time when 5 miles a day was a good speed for an army. He began gathering his forces for a massive blow against the Union army, which he hoped he could deliver at Gettysburg.

He couldn’t have known that a Union general, John F. Reynolds, was also hoping for a fight at Gettysburg because he’d already picked the best ground for his troops.

Next: Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops

The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move

We begin a series of the Post’s reporting on the Gettysburg Campaign with the initial news of the invasion.

As was its style, the Post presented the news on Page 2 of the June 27, 1863, issue. Beneath a simple headline, “The War,” it calmly announced the opening of what would become a pivotal moment in United States history:

“Since our last issue, we have had a considerable amount of excitement in this city, owing to the reports of a rebel inroad into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Exaggerated as those reports so far have been, it is better to be prepared for the worst, than to run any risk in such a serious manner.”

The early reports were not encouraging, the article added. The federal government had believed the Confederate army, under General Robert E. Lee, was camped near Chancellorsville, Virginia, directly across the Rappahannock River from the Union army. But starting in June, Lee had quietly begun withdrawing his 70,000-man army and marching them north, toward Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Ahead of him lay only small, scattered groups of Union forces. The first to encounter the advancing rebels were the 7,000 Yankees at Winchester, Virginia. They were quickly brushed aside and then, wrote the editors, Pennsylvania “lay open for the moment to any rebel body which had the temerity to enter.”

On June 19, the Confederates had crossed into Maryland. Two days later, they entered Pennsylvania. When they reached Chambersburg on June 28, they were still 160 miles from Philadelphia, and the Post’s offices. But those miles were nearly empty of any defending troops; the Union army had begun chasing after Lee’s army on June 11, but they were still south, unable to protect Philadelphia or Washington, D.C.

Yet the Post editors remained confident that the men of Pennsylvania could, and would, throw the invaders back across the Mason-Dixon Line. They assured their readers that a state militia could be quickly formed, and it would be far more effective than expected. “We hear, in these times, a great deal of underrating of the militia, as unreliable against veteran troops. Men are disposed to think it useless to trust our safety to such a force. But it seems to be forgotten that these militia are now upon the soil of their own states, fighting in defense of all that we hold dear.”

The Post explained that militia soldiers of the South had proven they could be highly effective in pushing back the Union armies that entered their states. (Though, when they had to fight beyond their state lines, their effectiveness disappeared. “They failed thus at Antietam, and South Mountain, and Perryville, and Mill Spring, and other places.”)

The North shouldn’t dismiss the fighting skills of raw recruits, the article maintained. They had heard witnesses from several battles say raw troops had performed just as well as veteran soldiers, sometimes even better. After all, it was a hastily formed militia that won the famous Revolutionary war battle of Bunker Hill, not to mention the War of 1812’s Battle of New Orleans.

Regardless of how well this green militia could fight, it was all the state had to defend itself until the Union’s Army of the Potomac could arrive. Pennsylvania’s governor called for 90,000 men to form a state militia, and hundreds of men traveled to Harrisburg to muster in. But when they arrived, many changed their minds upon learning the enlistment period of six months was longer than they thought necessary to meet the crisis.

Instead of criticizing their lack of spirit, the Post agreed with the volunteers’ decision not to enlist: “We do not censure in the least, those of our citizens who recently returned from Harrisburg, because their business engagements did not admit even a conditional pledge to serve for six months.” If the emergency were truly short-lived, they argued, there wouldn’t be any need for such a long enlistment.

Seeing the poor response, the governor reduced his request to 60,000 men and an enlistment of just three months.

While the debate about terms of service continued, the Confederates were helping themselves to the riches of Pennsylvania. Rebel troops who had long been living on short rations in a countryside ruined by war suddenly found themselves among the fat livestock and bulging granaries on Pennsylvania Dutch farms. Lee had ordered his men not to take from the local farmers, but to pay for what they requisitioned in (valueless) Confederate money. But many Confederates didn’t bother with such niceties as payment as they helped themselves to livestock, crops, furniture, clothing, and anything that could be loaded onto a wagon. Even worse, several hundred black Americans—some escaped slaves as well as fourth-generation free Pennsylvanians—were being seized and sent south to be sold as slaves.

No one in the North could be sure where Lee was headed, or what he had in mind. A report filed in the Post on June 28 indicated Harrisburg was the likely target. “The capital of the state is in danger. The enemy is within four miles of our works and advancing. The cannonading has been distinctly heard for three hours.”

Northerners knew that if Lee could take Harrisburg and its resources, he might easily turn southeast and seize Washington, D.C., just 120 miles away.

The Post’s editors never lost faith in Pennsylvania, or the Union. They believed Lee had made a bold move, but a hazardous one. “Properly improved on the part of the North and the Government, it may have the most favorable results. Let the friends of the Union seize now the propitious moment.”

What the Post didn’t know was that the Union army was closer than they, or Lee, expected.

Coming Next: Scrambling for Troops

The Post’s Civil War Half-Time Report

No country can win a war if its military strength isn’t matched by the determination of its people. If a war lasts too long, the public’s resolve runs out before the ammunition does. Case in point: it would have been extremely difficult if not impossible for the administration to maintain public support for the Vietnam War for its entire 14 years. More recently, our country’s determination has been challenged by 11 years in Afghanistan that have produced no decisive victories.

It was no easier 150 years ago, when the Union Army was still recovering from its December 1862 defeat at Fredericksburg. A growing number of Americans were demanding that President Lincoln negotiate with the Confederate government.

In this winter of discontent, the Post responded to the “gloom and dissatisfaction which secessionists are striving to spread over the land” by comparing the achievements of the Northern and Southern armies. In “What We Have Done and What the Rebels Have Done” (February 14, 1863), the editors credited the Union with 33 victories and the Confederacy with just 17.

This ratio of battlefield successes—nearly two-to-one—gives the impression the Union Army was outfighting its Confederate counterpart. But, if truth be told, Post editors were fiddling with the numbers for reasons that were hardly journalistic. The publication had an agenda to stir up waning enthusiasm for Lincoln’s war efforts.

There had been plenty of support for the war when it began in March 1861. Young men throughout the North rushed to enlist, their only worry being the war would be over before they had a chance to prove themselves. After all, they presumed, this would be a short, decisive war.

Then the long list of Union defeats began. In July 1861, the Confederates defeated General McDowell at Bull Run. In March 1862, they defeated General McClellan on the Virginia Peninsula. In August, they defeated General Pope, again at Bull Run. In December, they threw back General Burnsides at the battle of Fredericksburg.

The only place where the Union seemed to advance was in the western states, where Ulysses Grant was making a name for himself with a string of river victories. But Kentucky and Tennessee were a long way from Richmond, Virginia, the seeming invulnerable Confederate capital.

So Post editors rewrote the war to put the Union Army and Navy in a more positive light, using standards that consistently favored the North. For example:

• Three of the Union “victories” were not achieved by combat but reflected territories fell into Federal hands after the Confederates abandoned them.

• The “Evacuation of Manassas” was, in fact, a retreat.

• Two of the Confederates’ major wins at Bull Run were listed as just one victory.

• The editors counted five Union victories in the Peninsula Campaign, but gave the Confederates just one for winning the entire campaign. Moreover, everything the Union gained at Yorktown, Williamsburg, Hanover Courthouse, Fair Oaks, and Malvern Hill, they lost when driven from these battlefields as they retreated down the peninsula.

• Overall, the editors also didn’t weigh the Union and Rebel successes on the same scale: the South’s victories at Bull Run, the Virginia Peninsula, and Fredericksburg were a greater feat of arms than the minor battle of Drainesville or Mill Spring, but reading the Post article, you’d never know that.

Southerners would have recognized the true disparity in the two armies’ successes. They knew that, for all the North’s small victories, the South had kept them from advancing into Virginia for two years. What they couldn’t see in 1863 was how these little victories were quietly adding up and reducing their ability to wage war. The Confederacy still put its faith in winning with a decisive victory in one, big battle. It had been true in Napoleon’s day, but was no longer. Modern wars, waged across the breadth of a nation, were won by countless small wins with little glory and savage fighting.

But a campaign that relies on countless small wins, as we’ve seen in our current fighting in the Middle East, doesn’t look like progress.

Antietam: Our Post-Battle Report

September 17, 2012, marks the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single-day battle in American history.

Late in the second year of the Civil War, the Confederate army switched from defense to offense. General Robert E. Lee marched the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland, which had remained loyal to the Union.

He had recently defeated the Union forces at the Second Battle of Bull Run and decided it would be better to keep the momentum from this victory by a march into Union territory. Maryland was the natural choice; a large number of slaveholders in the state were strong supporters of the Confederacy. Lee hoped they would join his army and bring needed supplies. If he could score a victory against the Union forces, the Confederacy might win recognition from Great Britain and France. If so, the South could resume trade with Europe. The British Navy would break the Union’s blockade so that cotton could be shipped to the mills that were now laying idle from lack of material. Lincoln would have to fight the Confederacy and the British Empire. If Lee could win a victory.

The odds were in his favor. He was opposed by the Union’s General McClellan—an able administrator but a hesitant commander who always over-estimated the enemy. He had resisted Lincoln’s orders to move south toward Richmond. When Lincoln finally ordered him south, he was bluffed out of a strong position outside Richmond, Virginia, so close he could hear the church bells of the city.

Now Lee was coming at him. For the first time, the great Confederate commander would fight an offensive campaign, which was always more risky. It didn’t help that a union soldier found a copy of his strategy, copied for his generals. McClellan would never again have such an advantage. The Southern command soon realized that the orders had been found by the Union, but Lee stayed with his plan. McClellan attached Lee and, at Antietam, had the advantage for once.

Had he been a more decisive general—as determined as General Grant, for example—he might have defeated and captured Lee’s army. But McClellan wasn’t that bold or imaginative a general. And Lee was. The Confederates were able to withdraw their forces in the face of a large Union army.

All the same, it was a rare defeat for the Confederates. And for both sides, it was particularly bloody. In one day, nearly 23,000 Americans were killed, wounded, or missing.

Lincoln was shocked that General McClellan would not pursue the Confederate army and make it a decisive, war-determining battle. Yet, it was still a victory, and there had been very few for the North. Lincoln used the opportunity to announce a momentous change in policy, and a change in the direction of the war.

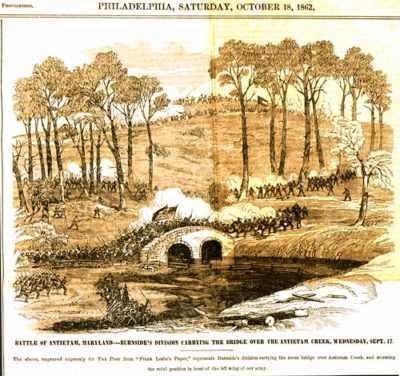

The following is taken from “The Recent Contests” from The Saturday Evening Post, September 27, 1862.

A week of anxiety ends with the joyful assurance that the rebel invaders have been forced to fly from “Maryland, My Maryland,” and entirely give up for the present the prospect of overrunning Pennsylvania.

It is evident that it was a most desperate struggle, in which though we can scarcely claim a decisive victory, the balance of advantages was decidedly in favor of the Union forces. The next day both armies were apparently too much exhausted to recommence the contest, the rebels probably secretly employing themselves in commencing their retreat into Virginia. On Friday, judging from our present advices, they completed their passage of the Potomac—with how much loss of men, trains, and artillery, we are yet unable to say. The amount of such loss of course will determine the extent of the disorganization they have sustained, and the character of the defeat they have suffered.

It is probable that the designs of the rebels in their recent movement were as follows:

1. To capture Harper’s Ferry and the 12,000 men at that place, by surrounding it, and moving on it from the North, from which side it is said to be least defensible, the Maryland heights being higher than the Virginia ones.

2. To replenish their supplies.

3. To raise Maryland in their favor, and largely recruit their forces.

4. To menace Baltimore and Washington, and the railroad communications of those cities with the North.

5. To invade Pennsylvania by way of the Cumberland Valley, allow us in this state to feel the ravages of war, supply themselves at will from our overflowing resources, and sicken us of the contest.

Of all these object the rebels have gained the first, and, it may be, in a degree, the second. Owing to shameful incompetency or treachery, Harper’s Ferry was captured. Whether the report of the recapture is true, we are at present unable to say.

But Maryland would not rise—even her secessionists will not put their property and lives in peril on so desperate a venture. For they see that even if the North were defeated, and the Union allowed to be dissevered, the North and Pennsylvania must at least insist on the Potomac for a border line.

To cross the Potomac is in fact to invade Pennsylvania—recent events have impressed this upon the great majority of our population. It therefore does not seem possible for Maryland to be severed from Pennsylvania without exposing both of them to great peril.