George H.W. Bush: Post Archives Reveal a Handyman of Politics

George H.W. Bush will be remembered most for his Presidential term, but the New England-born aristocrat served in many capacities of federal government before becoming the chief executive.

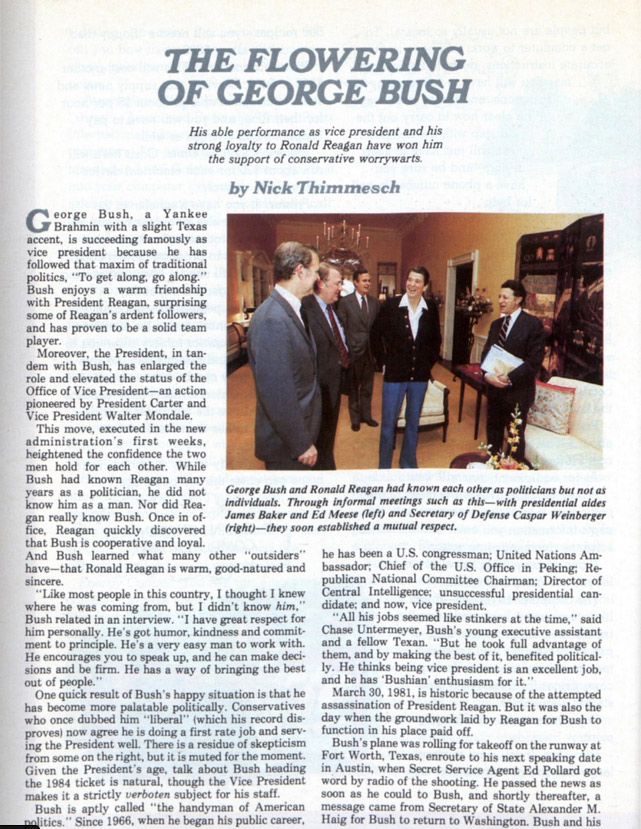

In “The Flowering of George Bush,” the Post covered his rise in a Republican party that was previously reluctant to trust the statesman for his perceived liberal tendencies. He had served as a House representative, U.N. Ambassador, Chief of the U.S. Office in Peking, Republican National Committee Chairman, Director of the C.I.A., and Vice President. “‘All his jobs seemed like stinkers at the time,’ said Chase Untermeyer, Bush’s young executive assistant and a fellow Texan. ‘But he took full advantage of them, and by making the best of it, benefited politically. He thinks being vice president is an excellent job, and he has ‘Bushian’ enthusiasm for it.’”

During the attempted assassination of Reagan in March 1981, Bush demonstrated his loyalty to the President as well as his willingness to rise to whatever the occasion called of him: “Everything went smoothly because the President had laid the groundwork,” Bush said. “It was a judgmental call for me on some occasions. I didn’t want to make it appear as though I was making presidential decisions, although I did have a substantial role.” Bush’s Vice Presidency continued in a larger scope, similarly to Walter Mondale’s before him.

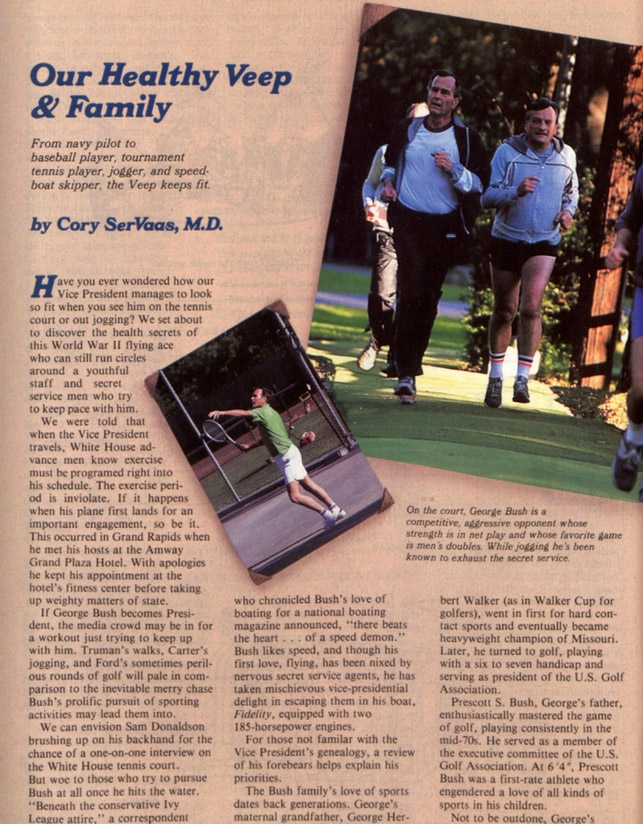

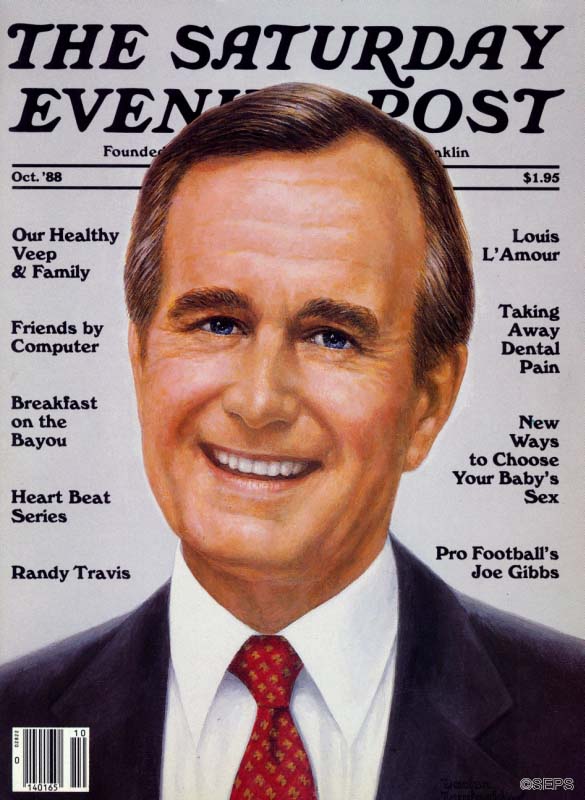

Years later, in 1988, Bush’s health habits were the focus of a feature, “Our Healthy Veep & Family,” by Saturday Evening Post Publisher Cory SerVaas, An avid golfer, runner, baseballer, and tennis player, the Veep was about to win his election when this magazine detailed the exercise habits of Bush Sr. Despite his busy campaign schedule, exercise was non-negotiable for the future President: “The exercise period is inviolate. If it happens when his plane first lands for an important engagement, so be it.” The article also featured a candid interview with his wife, Barbara. Mrs. Bush extoled her husband’s virtues and shared why she wanted to marry him: “I figured anyone who was as nice to his little sister as this young man was would surely make a fine father for our future children.”

Become a subscriber to gain access to all of the issues of The Saturday Evening Post dating back to 1821.

Considering History: The Presidency and Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

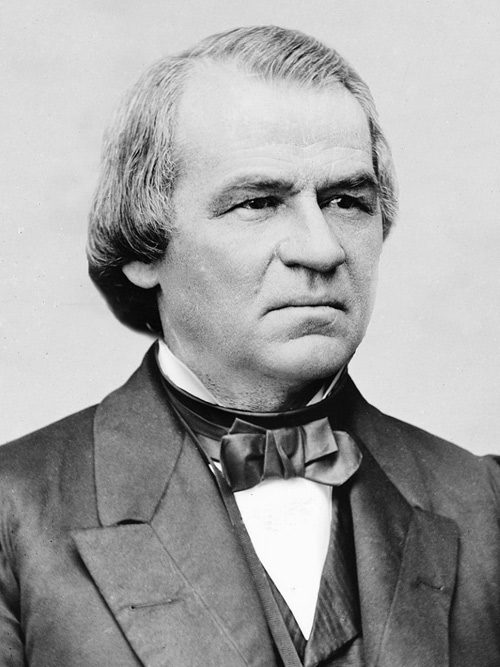

One hundred fifty years ago, Andrew Johnson became the first president of the United States to be impeached.

In 1864, facing a stiff challenge to his reelection campaign from Democratic nominee (and former Union general) George McClellan, President Abraham Lincoln decided to replace his current vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, on the ticket with a Democrat, Tennessee Senator and military governor Andrew Johnson. This choice allowed Lincoln and Johnson to run under the banner of the newly created National Union Party, emphasizing opposition to the Confederacy across the nation (and especially in contested border states like Tennessee). It was a pragmatic and clever strategic move, and likely contributed greatly to Lincoln’s eventual easy victory over McClellan in November 1864.

Yet as early as inauguration day, March 4, 1865, there were indications that Lincoln’s practical decision might have also been a mistake. Johnson may have been drunk at the inauguration (he had been witnessed drinking heavily at a party the night before and asked Hannibal Hamlin for two additional drinks just before the inauguration began), and in any case delivered a rambling, belligerent speech that was hastily cut off when Hamlin swore him in as the new vice president. And this ominous opening foreshadowed what would become, after Lincoln’s tragic April 14th assassination, one of the most divisive and destructive presidencies in American history.

Johnson continued his pattern of belligerent and bellicose public statements as President. When supporters came to the White House in February 1866 for a Washington’s Birthday celebration, Johnson addressed them in another long, rambling speech, highlighting his own accomplishments more than 200 times and attacking “men still opposed to the Union” who were “as much laboring to pervert or destroy [fundamental American principles] as were the men who fought against us.” When pressed by audience members, he named Congressman Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner (among others) as these enemies. In August and September of that year he would embark on a national speaking tour unprecedented for a sitting president; known as the “Swing Around the Circle,” the tour featured more than twenty rallies in which Johnson continued to attack Congressional “enemies” and make the case for his divisive Presidential Reconstruction policies ahead of the November midterm elections.

Those extreme Presidential Reconstruction policies truly defined Johnson’s divisive and disastrous administration, both on their own terms and in contrast to what might have been the case had Lincoln not been killed. Although Johnson had been perceived as a moderate on issues of slavery and sectionalism prior to and during the Civil War, as president he revealed himself to be both a staunch ally of the neo-Confederate South and a virulent white supremacist. Among his earliest presidential proclamations, Johnson first recognized a provisional Virginia government that was practicing policies of forgiveness toward ex-Confederates and then provided federal amnesty for nearly all ex-rebels. He went on to support additional amnesty policies such as one that allowed ex-Confederates (such as former vice president of the Confederacy Alexander Stephens) to serve in Congress; since Johnson’s administration likewise opposed proposals for African American voting rights, nearly all of the Southerners elected to Congress in these early post-war years were former Confederates.

Johnson’s opposition to post-war rights for African Americans went far beyond opposing suffrage proposals. In February 1866 he vetoed a bill that would have extended the vital operations of the Freedmen’s Bureau beyond the agency’s scheduled 1867 abolition, claiming that the law “would not be consistent with the public welfare.” In March of the same year he vetoed the groundbreaking Civil Rights Bill, arguing in his veto message that “the distinction of race and color is by the bill made to operate in favor of the colored against the white race.” Johnson also opposed the 14th Amendment and campaigned extensively (if unsuccessfully) against its ratification by the states, solidifying his administration’s overall hostility to nearly all Reconstruction measures that focused on civil rights rather than reintegrating the Confederate South into the nation as smoothly as possible.

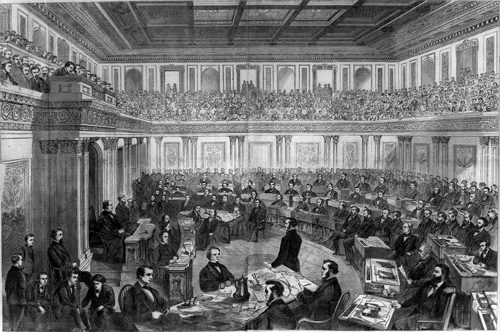

All those conflicts contributed to Johnson’s February 1868 impeachment by the House of Representatives, but it was his blatant, authoritarian violation of a specific law that directly precipitated the Congressional action. During his 1866 speaking tour, Johnson had pledged to fire Cabinet secretaries who did not agree with him (especially those who had been appointed under Lincoln), and in March 1867 he vetoed the Tenure of Office Act, which required Senate approval for such firings; Congress overrode his veto and passed the act into law. Throughout that year Johnson battled with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Lincoln appointee and advocate of Congressional Reconstruction, harsher treatment of former Confederates, and African American rights. In August, with Congress out of session and unable to approve any Cabinet actions, Johnson demanded Stanton’s resignation; when Stanton refused, Johnson suspended him and replaced him with General of the Army Ulysses S. Grant. The conflict continued for many months, and when Johnson permanently dismissed Stanton in February 1868 without gaining Senate approval as required by law, the House of Representatives voted 128 to 47 to impeach.

After a three-month trial in the Senate, featuring so much wheeling and dealing that Johnson and his allies would later be investigated by Representative Benjamin Butler for bribery, the Senate on May 16, 1868, fell a single vote short of the two-thirds majority necessary to convict the president. Johnson would complete the remainder of his term, but as a deeply unpopular president; even his own Democratic Party denied him the 1868 presidential nomination in favor of former New York Governor Horatio Seymour (who would lose to the Republican nominee Ulysses S. Grant). On Christmas Day, 1868, Johnson took advantage of one of his last opportunities to further his neo-Confederate and white supremacist agendas, issuing a blanket amnesty that covered all former Confederates including the Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Johnson’s political career did not quite end with Grant’s election, as he made a successful run for a Tennessee Senate seat (at that time still decided by the state legislature) in early 1875. He would only serve for a few months before dying unexpectedly of a stroke in July, but during that time expressed his neo-Confederate views one last time (his only official remarks during his brief Senate term), criticizing Grant’s use of federal troops in Louisiana and asking, “How far off is military despotism?” One final belligerent and extreme remark from a president who remains one of the most divisive and destructive in American history.

Cover Gallery: Presidents

The Saturday Evening Post has featured many U.S. presidents on its cover in its nearly 200-year history. Here is a gallery of the men who have helped shape our nation.

By Karl Kleinschmidt

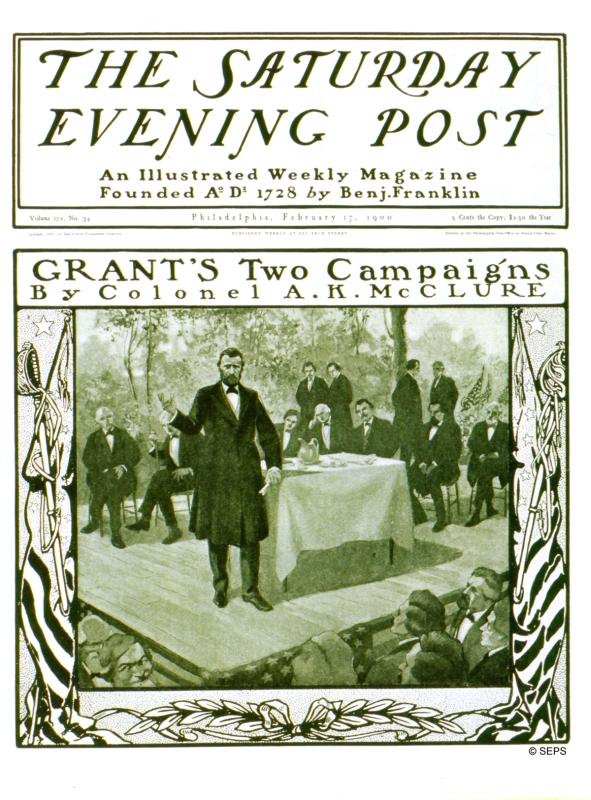

February 17, 1900

Fifteen years after his death and 23 years after leaving office, Grant appeared on the cover of the Post, in one of a series of articles by Colonel A. K. McClure on “How We Make Presidents.” Grant oversaw the elimination of Confederate nationalism and slavery, protected African-American citizenship, and supported industrial expansion.

By Sarony & Bell

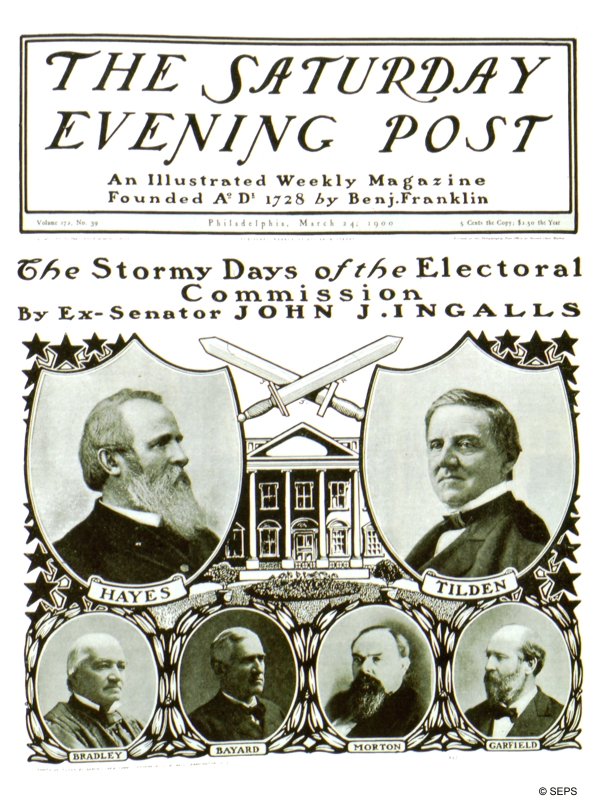

March 24, 1900

The election of 1876 was one of the most contentious in U. S. history. It was one of only five elections in which the person who won the most popular votes did not win the election. At one point, Tilden had 19 more electoral votes than Hayes. But a deal was brokered in which 20 disputed electoral votes were awarded to Hayes in exchange for withdrawal of federal troops from the South, putting Hayes in the White House by one vote.

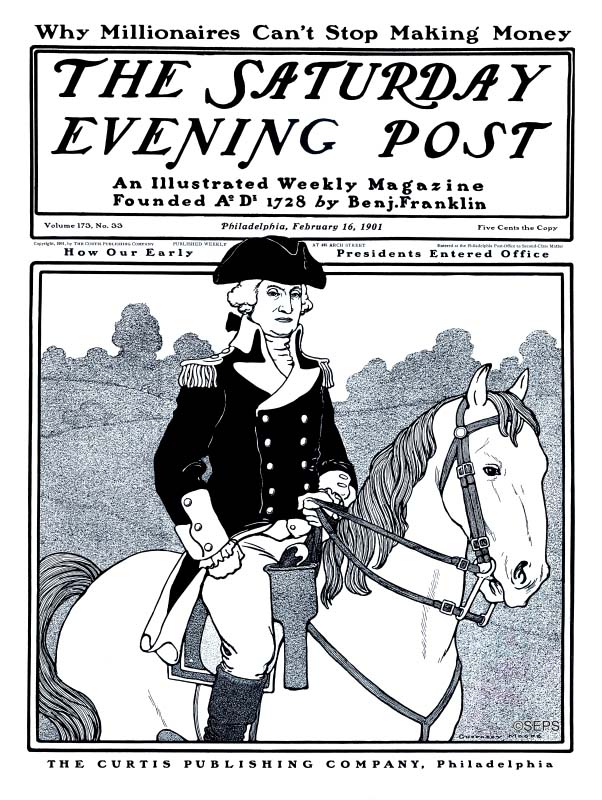

By Guernsey Moore

February 16, 1901

As he was handing over the reins of the presidency to his successor, John Adams, Washington wrote, “I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy.”

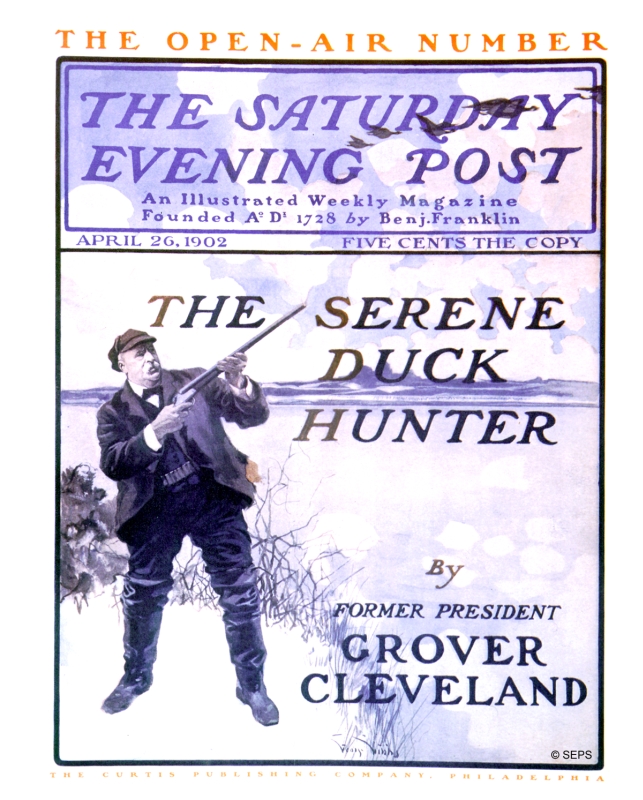

By George Gibbs

April 26, 1902

Grover Cleveland was only U. S. President to serve two non-consecutive terms in office. He appeared on seven Saturday Evening Post covers and wrote several articles for the magazine on hunting, fishing, and the plight of democracy (not necessarily in that order of importance). He is remembered for being the only president to marry while in the White House, and for his deathless statement, “What is the use of being elected or re-elected unless you stand for something?”

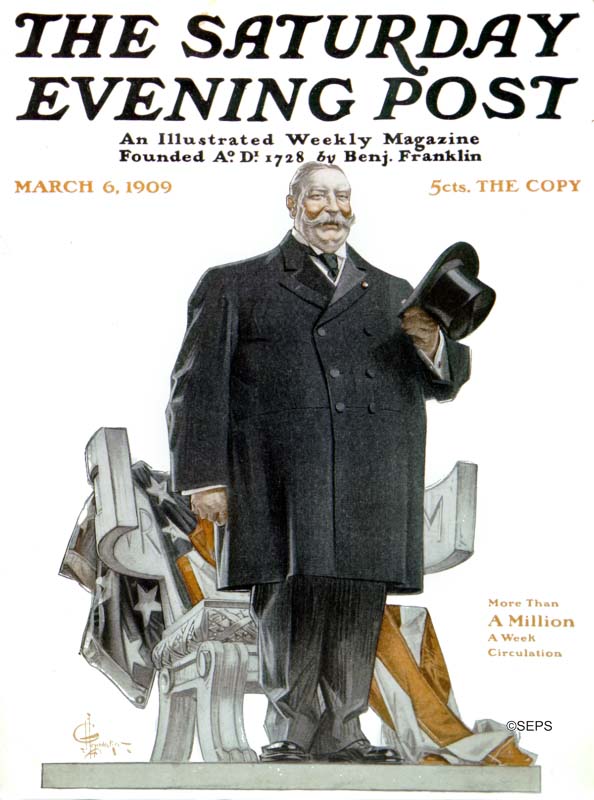

By J. C. Leyendecker

March 6, 1909

An article in this issue of the Post proclaimed Taft to be “the heaviest President, the most traveled President, the best-natured President and the first golf player to occupy the White House.” He was among the most amiable and least ambitious men to be elected to the office. He continued most of the policies of his predecessor and friend, Teddy Roosevelt, but the two became estranged and ran against each other in 1912.

All his life, Taft tried in vain to reduce his weight. He reached 355 pounds while he served unhappily as president. He was also the only president to also serve as a justice on the Supreme Court, where he was far happier.

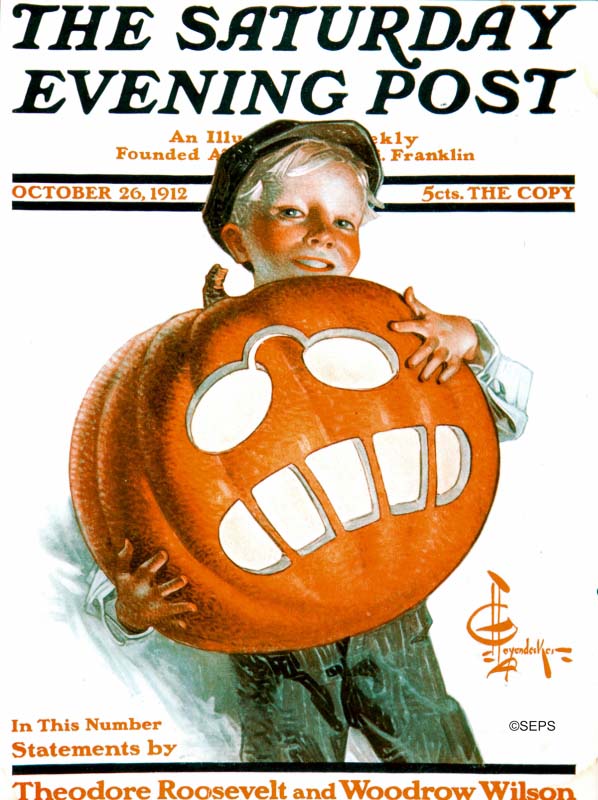

By J. C. Leyendecker

October 26, 1912

The Post was fascinated and charmed by Theodore Roosevelt, an energetic, progressive, young president who interrupted the long line of serious old men in the White House. Post editorials applauded his campaigns against “malefactors of great wealth” and his enthusiasm for making the U.S. a global power. Coming to the presidency in 1901 after President McKinley was shot, he was elected to a full term in 1904. He stepped aside in 1908 to let his friend, William H. Taft, successfully run for office. But in 1912, when this boy carved his pumpkin with TR’s toothy grimace and pince nez glasses, he was trying unsuccessfully for another term.

By J. C. Leyendecker

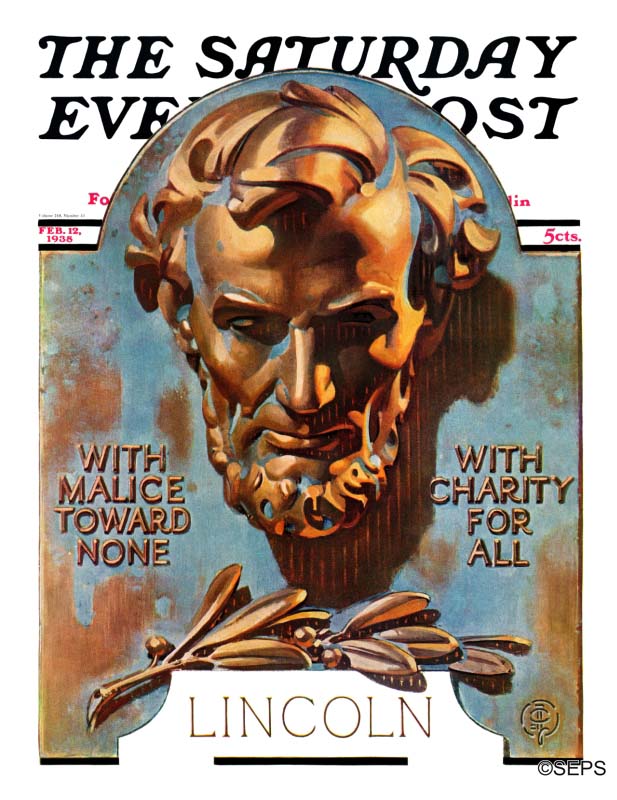

February 12, 1938

In 1862, with the country at the end of a Civil War, Lincoln called on Americans to face the challenges ahead without looking backward. He also reminded members of Congress that they would all be remembered for what they did in those perilous times:

“The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

“Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.”

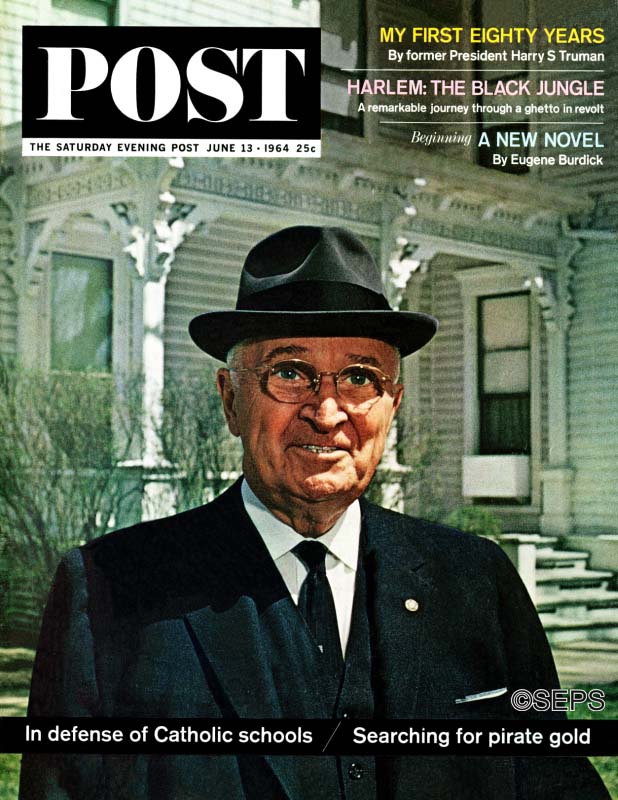

By John Launois

June 13, 1964

This photograph of former President Truman was taken in front of his Independence, Missouri home. In an article that Truman wrote for the Post, the 80-year-old looked back over his controversial career and explained the principles that guided him in making the most difficult decisions of his Administration — including the “firing” of Douglas MacArthur.

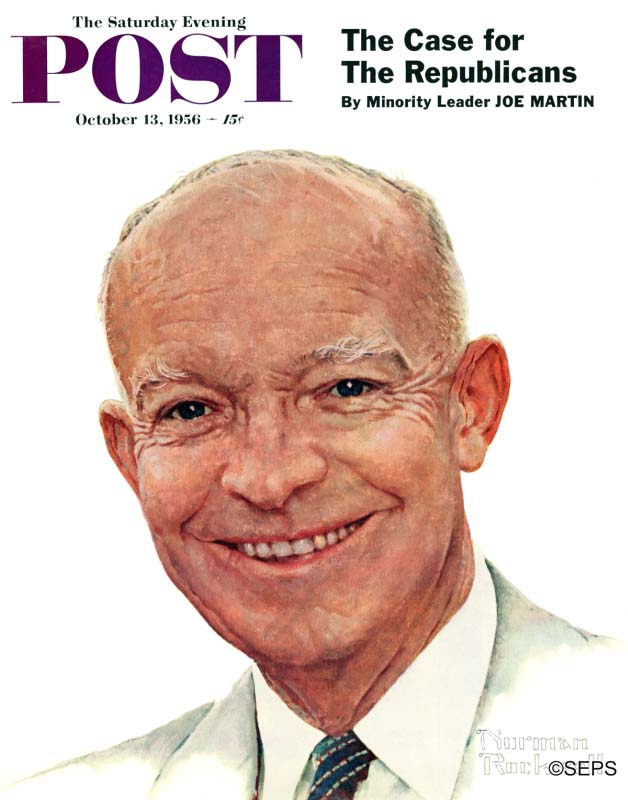

By Norman Rockwell

October 13, 1956

The Post hadn’t featured a sitting president on its cover since Taft’s appearance in 1909. A popular president, Eisenhower authorized the establishment of NASA, invoked executive privilege to help end McCarthyism, expanded social security, launched the interstate highway system, and established the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency which led to the development of computer networking and graphical user interfaces.

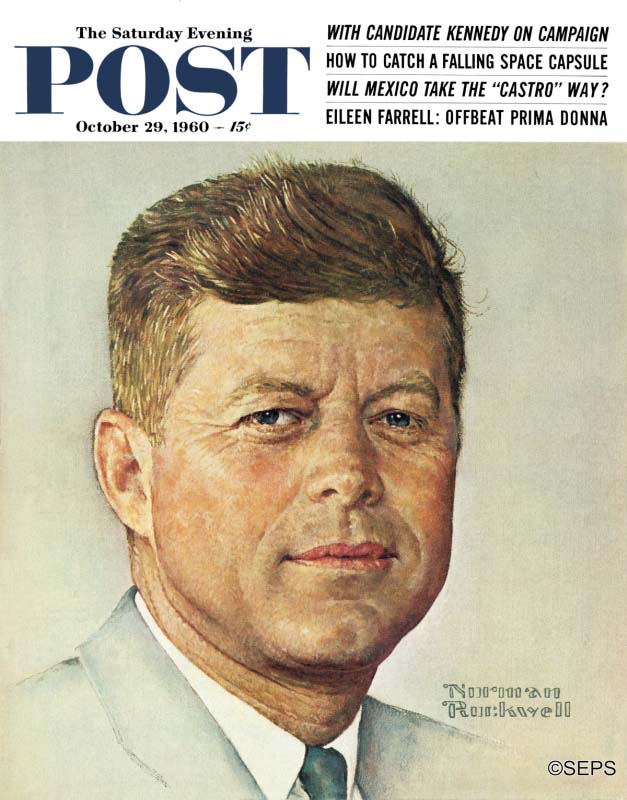

By Norman Rockwell

October 29, 1960

Among his many better known accomplishments, Kennedy also won a Pulitzer Prize (for “Profiles in Courage”), was awarded a Purple Heart, and donated his salary to charity. He represented the new generation of politicians: he was young, good-looking, smart, and funny, and drew international admiration. Kennedy spoke of idealism at a time when the country wanted to move on to new horizons, but his aggressive stance against communism brought the country close to one war and involved it in another, in Vietnam.

This Rockwell portrait appeared a second time when the Post ran its memorial issue after Kennedy’s assassination.

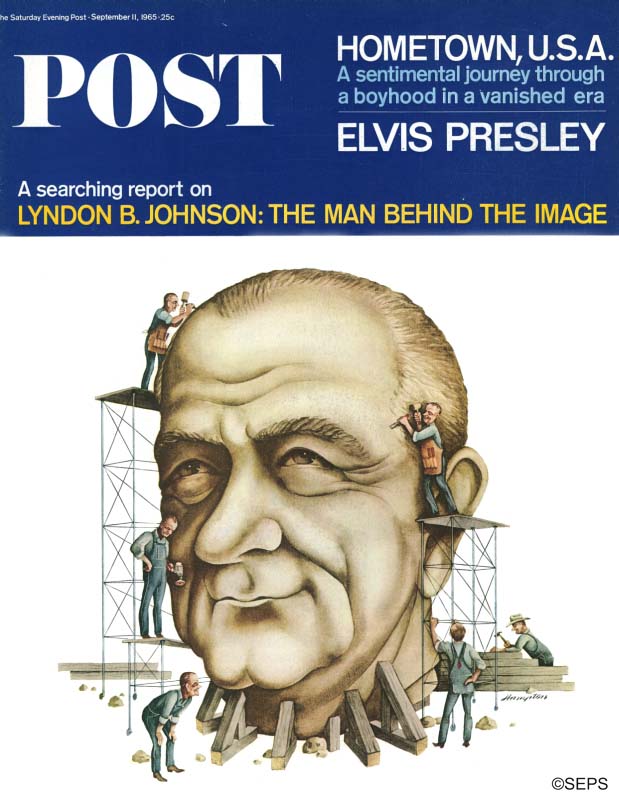

By Blake Hampton

September 11, 1965

President Johnson was a politician’s politician, and he was a paradox. He was cynical and calculating enough to be a powerful force in Washington, but also a champion of the poor and the man who launched a “War on Poverty. Johnson signed several civil rights bills that banned racial discrimination in public facilities, interstate commerce, the workplace, and housing. He signed the Voting Rights Act and the Immigration and Nationality Act into law. When he came to the White House after Kennedy’s assassination, he enjoyed a long honeymoon period with the press. But he lost the support of the media, and many Americans, with his determination to continue sending American soldiers to Vietnam.

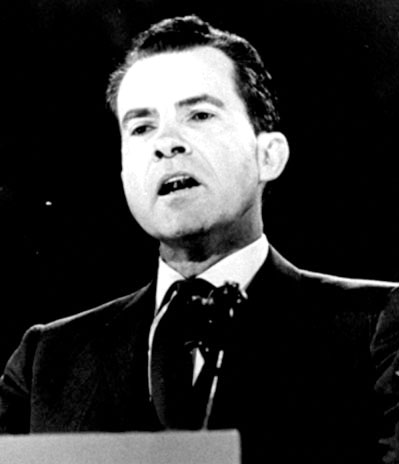

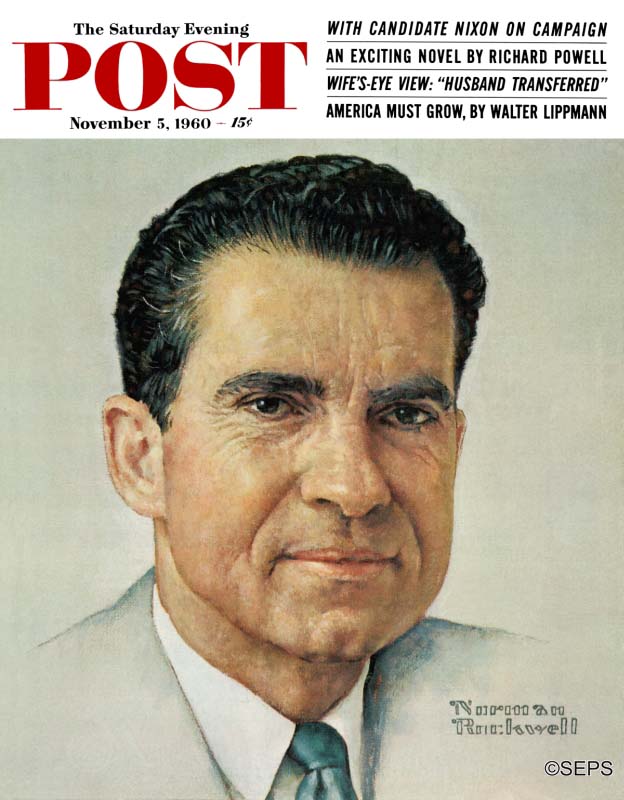

By Norman Rockwell

November 5, 1960

President Nixon is best remembered for the Watergate scandal and his subsequent resignation, but he also opened diplomatic relations with China, initiated détente with the Soviet Union, and established the Environmental Protection Agency. He ended U.S. involvement in Vietnam, and supported the Equal Rights Amendment, affirmative action, and the food stamp program. It was ironic that a man who rose in politics through his anti-communist stance made such significant progress with the communist governments of Russia and China.

Rockwell painted this portrait of candidate Nixon nine years before Nixon won the presidency.

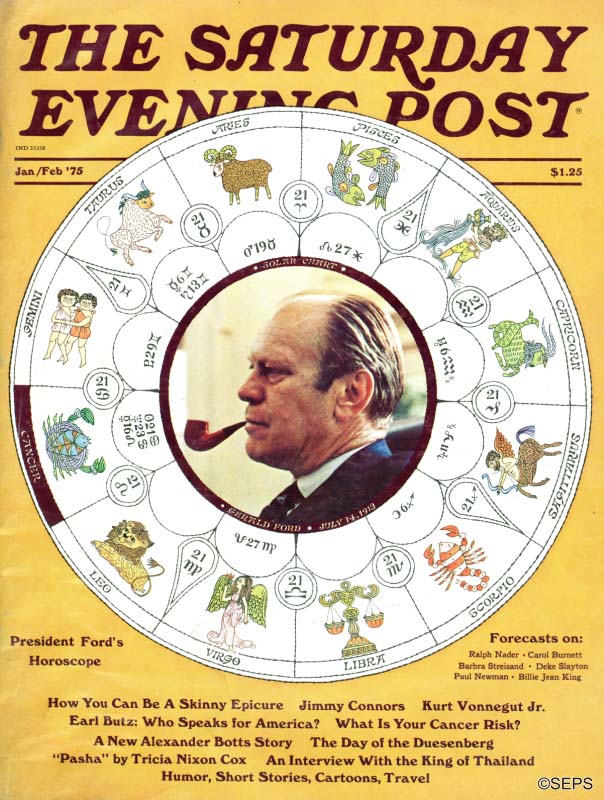

By J. Moore

January 1, 1975

In this feature in the Post, “astrologer to the stars” Carroll Righter analyzed President Ford’s astrological profile, terming him a Moonchild. Ford has the distinction of being the only person to have served as both Vice President and President of the United States without being elected to either office. It has not been determined if the alignment of the stars or planets was a factor.

Entering the White House abruptly when President Nixon resigned, he drew broad support by pardoning the men who’d avoided serving in Vietnam by illegally dodging the draft. But much of his popularity melted away when he also pardoned Nixon, sparing the nation a long, rancorous, divisive spectacle of a trial.

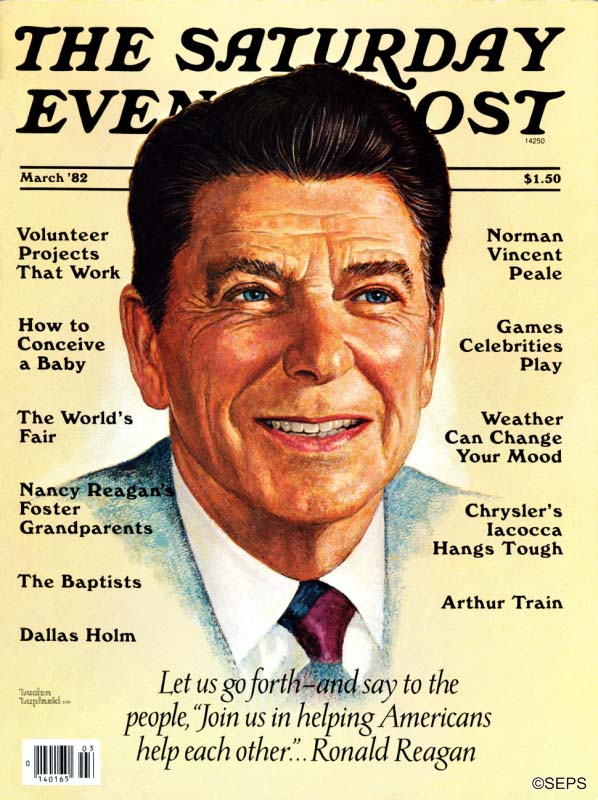

By Lucian Lupinski

March 1, 1982

Once a Democrat, Reagan switched to the Republican party as his views became more conservative. As president, he supported Afghan rebels opposing Russia’s invasion of their land and pushed for a space-based missile system to protect America from a nuclear attack. In the end, though, he was the president whose policies and tactful diplomacy with Russian leaders would end the Cold War.

By Lucian Lupinski

October 1, 1988

George H. W. Bush appeared on the Post cover when he was still vice president, but was poised to win the presidential election, held a month later. He is the oldest living former president and vice president.

Bush continued many of Reagan’s policies, but he bridled when journalists compared him unfavorably to the charismatic Reagan. He was portrayed by some as being weak, sheltered, and a wimp. Yet it was Bush, not Reagan, who served in World War II and survived being shot down as a Navy pilot. His single term was noted for his authorization of the military overthrow of a corrupt dictator in Panama and the smashing of Iraq’s force in Kuwait though Operation Desert Storm.

FDR Asks, ‘Can Vice Presidents Be Useful?’

Lost in the noise and excitement of a presidential campaign is the quieter contest for the vice presidency. With few exceptions (the 2008 competition between Joe Biden and Sarah Palin being one), it never draws the same public interest as the presidential race because it’s really not a contest between vice presidential candidates.

The vice-presidential hopefuls are more or less surrogates for their presidential running mates. And once elected, the vice president’s job doesn’t draw much fascination from the public. The VP presides over the Senate, attends public functions not important enough to merit the president’s attendance, and, of course, remains ready to step into the big job if the president is killed or incapacitated.

Long before he ran for president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt tried out for the Veep’s job. He’d been appointed assistant secretary of the Navy in 1913 and worked in that capacity through the First World War. Shortly afterward, he was offered a chance to campaign with the Democratic presidential nominee of 1920, James M. Cox.

Being chosen as Cox’s running mate was a step up for FDR, but he was under no illusions about the importance of the VP position. He envisioned bigger things for the office. And so, in 1920, the Post published his article, “Can the Vice President Be Useful?” in which he suggested a new role for the vice president that would help make Congress more efficient.

We aren’t giving away anything by telling you that no one took up Roosevelt’s suggestion. Still, it’s an intriguing idea to give the VPOTUS more substantial work for the position’s $230,700 annual salary.

Can the Vice President Be Useful?

By Franklin D. Roosevelt, Reported by Donald Wilhelm

Excerpted from an article originally published on October 16, 1920

Library of Congress

There is probably no better example of what might be called the industrial waste at Washington than is shown by the traditional conception of the duties of the vice president. Here is a man supposedly fully capable in an emergency to act as President of the United States; who has been nominated and elected by exactly the same procedure as that surrounding the nomination and election of the president himself. No precaution which the framers of our Constitution could design was neglected to assure the people that their vice president would be chosen with the same care with which the president is chosen and elected to office by the will of the majority of the citizens. Yet the only official work devised for him to do is to preside over the Senate, which is in session hardly more than half of each day and hardly more than half the days of each year, and, moreover — notably during long set speeches — is often presided over by a senator called to the chair by the vice president.

I believe that Washington must be reorganized, that voters will insist upon it, and I hope sincerely that the vice president’s job will be one of those which will be attended to. Just what the added duties of the vice president will eventually be, of course, no one can forecast. The most one can do certainly is to suggest the background of the office and of the government and indicate what might be done in the foreground, by the vice president especially.

Clearly, at the very outset, two facts are evident: First, such functions as the vice president may perform strictly in relation to the Senate are for the Senate itself to decide; second, the reorganization of the governmental machinery cannot be achieved in any event by the Senate alone, by Congress alone, or by the president and the department heads alone. All must lend a hand if reorganization is to be achieved at all, and the vice president with the rest.

In a large sense the first step must come in betterment of the relations between Congress and the White House. I think the first count in the nation’s bill of complaint is that the legislative and executive families are all but disastrously too far apart when they are of different political faiths, and still too far apart when they are of the same political faith. In some countries having a parliamentary form of government — England, for instance — the prime minister, who bears analogy to our president, and the members of the cabinet have access to the floors of their legislative bodies, where, though they cannot, of course, vote, they can yet outline personally the pros and cons of their policies. It is worth noting that President Washington several times occupied a seat on the floor of the Senate in order personally to make his views known. Years later, an attempt was made to encourage this practice and to establish it by joint resolution. Again, it is worth noting that President Wilson, in order to present his views to Congress most successfully, personally addressed it on various occasions. The question accordingly comes to mind: Cannot the vice president so utilize his high office as to help bridge the dangerous and increasing gap between Congress and any administration?

The Family Feud

It is my thought that reorganization itself, not only of all the factors that bear on the relationship of Congress with the office of the president but the reorganization of the executive departments themselves, can never be achieved until Congress and the White House are in closer touch. Certainly no commission of experts called in from outside by either Congress or the president can succeed with the gigantic problem of reorganization of this, the biggest and most intricate business in the world.

The proof is in: President Taft tried and signally failed after his commission had all been ground up between the upper and the nether millstones. It is certain that no Congressional commission can succeed in reorganizing the executive departments and bureaus without the cooperation of the president and the heads of the departments and bureaus, though such a body as the Congressional Commission on Reclassification of Government Personnel, which does not disturb the various entities, might succeed in its particular task. And certainly no president can achieve reorganization of even the executive departments without such cooperation from Congress as will result in necessary legislation. It follows, in other words, that harmony is the shibboleth.

The question, then, that occurs to one at this juncture is: Would it be possible for the vice president, who is not tied down to a desk, to help? Especially in relation to problems where the jurisdiction or control does not rest in one department but partly in one and partly in others? In other words, wouldn’t it be practicable for the vice president, at the request of a department head or at the request of the president, to study such a situation and report?

Anyone who has grappled with governmental inertia will understand why such suggestions are in point. Like most young men, when I went to Washington I felt that the traditional inertia in the departments was not a real thing but rather an excuse for laziness. I discovered very soon that though it is intangible and therefore all the harder to grapple with, it is as real as anything in the world, as real a thing as if it had flesh and blood, though you can never put your finger just here or there and say: “Here is the monkey wrench in this machinery!”

Liaison Service

It has been said very frequently, by executives in Washington, and others, that the trouble all lies with Congress.

But the broader view is that the trouble is the result of lack of plan, or, more accurately, our inability to adjust our tremendous growth to the old, existing plan; and running that idea back, you soon discover that the dire need of adjustments — in other words, the dire need of reorganization — is largely due to the wide gap between the executive and the legislative families.

We return thus to our starting point — the need of utilizing every possible aid in overcoming the gap between Congress and the executive branch of the government — and the desirability of making fuller and more satisfactory use of the vice president in overcoming that gap; in Congress, where his duties and prerogatives are in the hands of the Senate, and in the White House and executive departments, where his usefulness depends largely upon his relationship to the president and his willingness to aid the president.

There is hardly any limitation upon the ways in which the vice president might be of service to the president. He might serve as an executive aid to the president, and in that capacity could easily enough, even if he did not possess such executive authority as might without a Constitutional amendment be granted him, exercise considerable influence through his close relationship with the president. He could, at the request of the president, serve in relation to the determination of large matters of policy that do not belong in the province of a member of the president’s cabinet. He might serve as a kind of liaison officer to Congress and aid perhaps in carrying the large burden of interpreting administration policies to Congress and to the public.

Conclusively, when one has thus considered the background of our government and realized the urgent need of accomplishing reforms in the foreground, the desirability of making fuller and from every approach more satisfactory use of the vice president is apparent. The question, then, resolves itself into the problem of ways and means. And in meeting the problem of ways and means, the most that one now can do is to trust to American resourcefulness.

The Worst 10 1/2* Vice Presidents

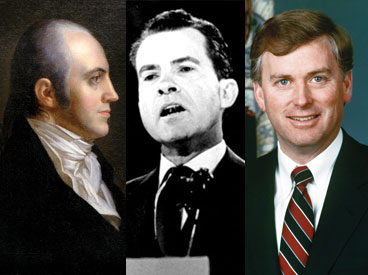

What do Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Hannibal Hamlin, and Millard Fillmore have in common? All are former vice presidents of the United States. Two are on Mount Rushmore; two are not.

What do Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Hannibal Hamlin, and Millard Fillmore have in common? All are former vice presidents of the United States. Two are on Mount Rushmore; two are not.

Forty-seven men have occupied the office of vice president, and while they were in there, they did little other than serve as presiding officer of the Senate, their only constitutional mandate.

Vice presidents were chosen more for perceived vote-getting abilities than because of genuine credentials as public servants—which many had. Even so, an aura of veiled weirdness has hovered over the office for more than two centuries.

In 1788, the U.S. held its first presidential election under a flawed system: The man with the most electoral votes got to be president, and the man finishing second became vice president. President John Adams, elected following Washington in 1796, and Vice President Thomas Jefferson detested each other. Imagine George W. Bush with Al Gore as vice president or an Obama-Romney administration, and you’ll understand.

In 1800, Jefferson and Adams faced off—the first time two former vice presidents mutually sought the presidency. But Adams finished third while Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied with 73 votes each. Burr had agreed in advance to serve as Jefferson’s vice president, and that’s how things ultimately worked out.

Jefferson’s near-disaster led to the passage of the 12th Amendment, which required electors to cast separate votes for the two offices. This spared us, up to a point, acrimony between the two top office holders. Since the first vice president was elected in 1788, a motley of murderers, traitors, bribe takers, and outright crooks have paraded through the vice presidency. What’s more, during the 224 years between 1788 and 2012, the office has stood vacant on 18 occasions for a total of almost 38 years.

The nation survived not only those 18 vacancies but also the 10 and one-half vice presidents we examine below.

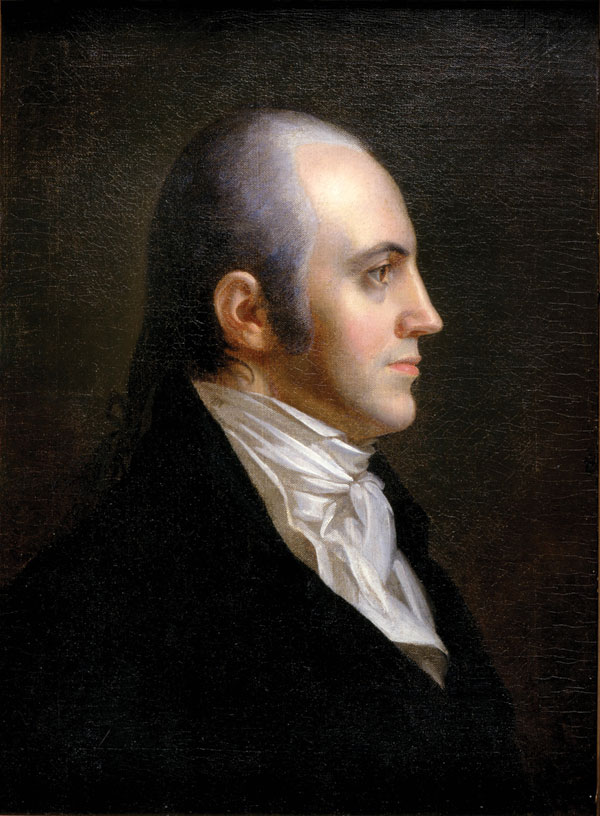

Aaron Burr

(1801-1805)

Our third vice president, Aaron Burr of New York, set the tone of lunacy that so often defines the office. Burr killed Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in an illegal duel and got himself charged with murder in both New York and New Jersey. After leaving office, shady land deals in the western wilderness got him charged with treason. He was never convicted of either crime.

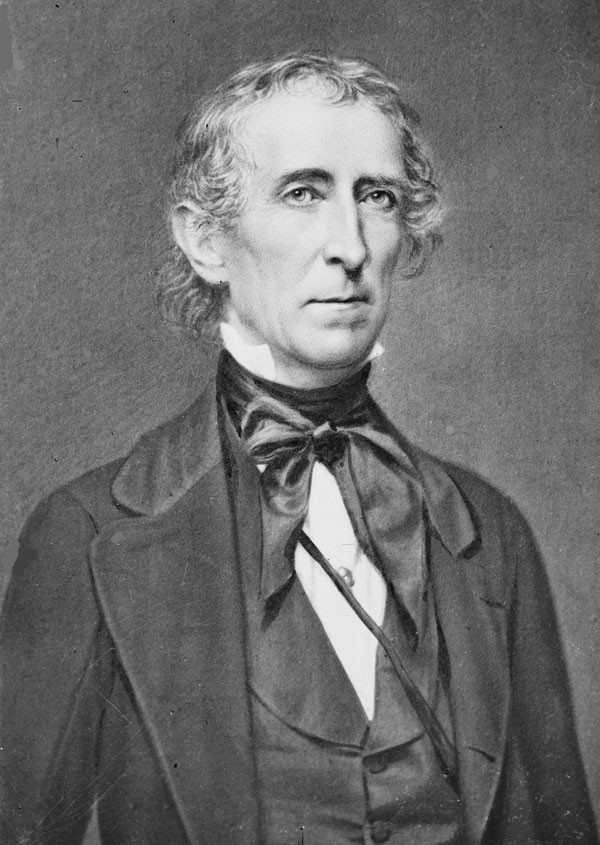

John Tyler*

(1841)

How do you get one-half of a vice president? John Tyler of Virginia did it this way. He was the “too” of the 1840 campaign slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” The “Tippecanoe” half of the ticket was William Henry Harrison who spoke for three hours at his rainy inauguration, caught pneumonia, and died 31 days later, making Tyler our shortest-serving vice president.

Incredibly, though the Constitution provided for a vice president, it did not state expressly that the vice president would assume the office of president following a chief executive’s death. A quick-acting Congress rectified this … in 1967.

Before even being elevated to the presidency, Tyler signaled his lack of interest in his elected position. In fact, immediately after Harrison’s inauguration, Tyler left Washington and didn’t return until he was summoned at the president’s death. On his return, Tyler resisted congressional attempts to name him “temporary” or “acting” president and served almost a full term as a no-asterisk president. In that post, however, he was unremarkable and historians have called him weak. He so alienated his party that he was denied its nomination for the election of 1844.

Millard Fillmore

(1849-1850)

Millard Fillmore, who became chief executive in 1850 when President Zachary Taylor died of natural causes, was the first vice president of urban legend, though not until 43 years after his death. In a 1917 column, humorist H.L. Mencken wrote that Fillmore had introduced the first bathtub into the White House. This was an outright hoax, but people believed it, then and now.

Mencken came clean in 1949, but the story remains alive. As a part of “Fillmore Days” in Moravia, New York—near Fillmore’s birthplace—wheeled bathtubs race through the city’s streets.

William Rufus King

(1853)

King served only slightly longer than Tyler. He was elected with Franklin Pierce in 1852 and served 46 days before expiring. King is best remembered as our only bachelor vice president and as the longtime roommate of James Buchanan, who in 1856 became the only bachelor elected president.

The Buchanan-King duo was known around Washington as the “Siamese twins,” and President Andrew Jackson referred to them as “Aunt Fancy and Miss Nancy.” King’s brief tenure, not his private life, places him on our list.

A footnote to the bachelors: Buchanan’s vice president, John C. Breckenridge, finished his one term and left town in 1861 to join the Confederates. He was one of two vice presidential turncoats, the other being Tyler, who served as a Confederate legislator.

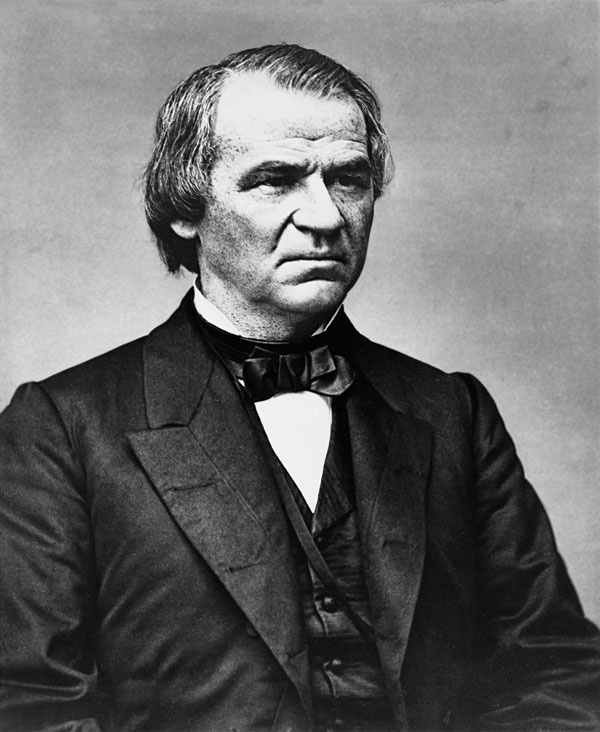

Andrew Johnson

(1865)

Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat and a tailor by trade, ran with Abraham Lincoln in 1864 on something called the National Union ticket. He got things rolling by showing up apparently inebriated for his inauguration. (Honest Abe later said, “Andy ain’t a drunkard”—possibly the only time a president publicly defended a vice president.)

When Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, Johnson took office and found himself at loggerheads with the Republican administration. A former slave owner, Johnson displayed few concerns for the rights of recently freed slaves and was ultimately impeached by the House and put on trial in the Senate.

Johnson avoided expulsion by a single vote and in 1868 joined the growing parade of vice presidents who gained the presidency but were denied their party’s nomination.

Schuyler Colfax

(1869-1873)

Selected to run with Civil War hero Ulysses Grant in 1868, Colfax had previously served as Speaker of the House of Representatives. Grant, 46, and Colfax, 45, formed the youngest team ever to run for the two offices until Bill Clinton and Al Gore ran in 1992.

A native New Yorker and friend of editor Horace Greeley, Colfax took Greeley’s advice and moved west to South Bend, Indiana. He served as a U.S. Representative from his adopted state. During Grant’s first term, Colfax’s involvement in the Crédit Mobilier of America railroad scandal transpired. (Ironically, Colfax would later drop dead on a railroad station platform after walking three-quarters of a mile in subfreezing Minnesota weather.) He was not nominated for a second term.

He was the first of two vice presidents to preside over both houses of Congress, the other being John Nance Garner. Appropriately enough for a vice president, he was a member of the International Order of Odd Fellows.

Colfax is buried in South Bend, one of four vice presidents buried in Indiana. Keeping their distance, the others are buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

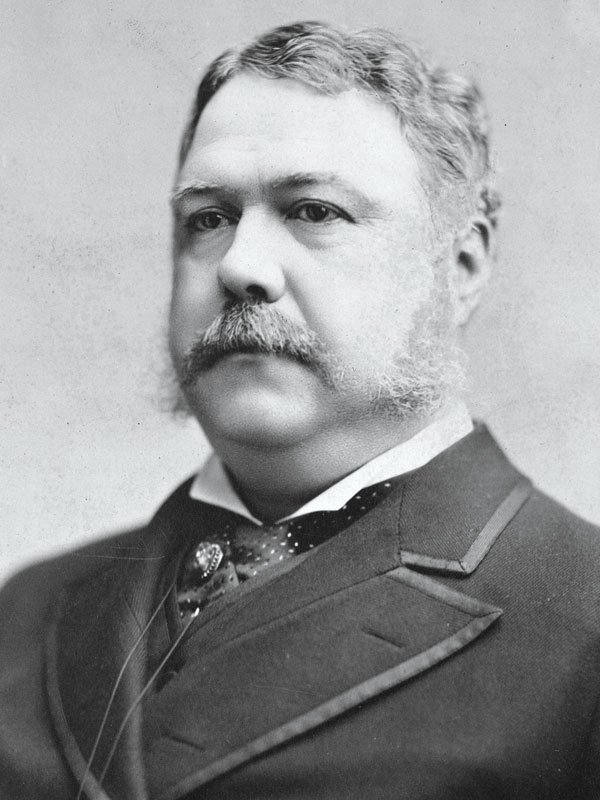

Chester Arthur

(1881-1885)

Utopian religious nut Charles J. Guiteau shot President James Garfield on July 2, 1881, and announced “Arthur is president now!” He was wrong. It took Garfield until September 19 to die.

Arthur came to the vice presidency in a cloud of controversy. He’d been removed from his post as collector of the port of New York 10 years earlier amid charges of corruption. But once in the White House, Arthur is credited by most historians as a reformer. None other than Mark Twain praised his presidency. But the high-living, overweight gourmand would not serve a second term. After learning he was dying of kidney disease, Arthur made only a half-hearted attempt to secure his party’s nomination, and he left office in 1885.

Charles G. Dawes

(1925-1929)

Dawes could not get along with his boss Calvin Coolidge and refused even to attend cabinet meetings. The first time he addressed the Senate, he made a speech denouncing the way it conducted business. Later, he napped through a decisive vote, which resulted in a Coolidge appointee losing his job. Dawes is one of two V.P.s to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. (The other was Teddy Roosevelt.) Dawes received his accolade in 1925 for the Dawes Plan, aimed at restoring German economic equilibrium after World War I. It ultimately did not work, but he got to keep the prize.

Richard Nixon

(1953-1961)

Richard Nixon, elected with Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, gave generously to the dusty storehouse of vice presidential trivia. Asked what Nixon’s principal contribution to foreign affairs was, Eisenhower replied, “If you give me a week, I might think of one.”

To be fair, some historians would counter that Nixon did a good job presiding over Eisenhower’s cabinet for six weeks while the president recovered from a heart attack. (See “Richard Nixon—A Great President!” The Contrarian View, Nov/Dec 2012.) Nixon was the only vice president to be elected president after leaving office and suffering through two opposition presidents: Kennedy and Johnson.

When Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned following a bribery scandal in 1973, Nixon appointed Gerald Ford of Michigan to the post. Then, when Nixon himself resigned in the wake of the Watergate scandals, Ford became president and appointed Nelson Rockefeller vice president.

The presidential nomination of a vice president—who went missing for whatever reason—was not possible until 1967 when the 25th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified.

Spiro Agnew

(1969-1973)

Spiro Agnew oozed onto the political scene with Nixon in 1968. A former governor of Maryland, Agnew was the first vice president to serve his master as an attack dog, and relished uttering such phrases as “nattering nabobs of negativism” to define the Washington press corps. As we have seen, the press had the last laugh.

Dan Quayle

(1989-1993)

Dan Quayle, the fifth vice president elected from Indiana, first got himself roasted in the 1988 vice presidential debate by Democrat Lloyd Bentsen: “You’re no Jack Kennedy.” He then went on to publicly misspell “potato” as “potatoe.” Investigation later revealed that he’d been given a flash card containing the errant spelling, but the damage was done.

Quayle, a sitting U.S. Senator, took office with George H.W. Bush and was somehow invited to run for a second term. In Quayle’s hometown of Huntington, Indiana, stands the Quayle Vice Presidential Learning Center. According to Roadside America, visitors can view such exhibits as Dan Quayle’s grammar-school report cards (Bs and As, thank you very much) and one of Millard Fillmore’s hats.

Were there any good vice presidents? Beginning with Theodore Roosevelt in 1901, there were a few. And remember that, under the original electoral system, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were vice presidents.

Teddy Roosevelt won both the Republican nomination for president in 1904 and the subsequent election. In 1912, he ran unsuccessfully for president with his ill-starred Bull Moose Party (see “100 Years Ago—A Chaotic Presidential Election”). By then, however, he had won the Nobel Peace Prize, served as New York City’s police commissioner, Governor of New York, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and established himself as a dedicated conservationist and successful reformer.

John Nance “Cactus Jack” Garner from Uvalde, Texas, served as vice president for two terms under Franklin Roosevelt. He is most famous for his definitions of the office he occupied, but he was also a former Speaker of the House and a power in Democratic politics. He might well have become president had FDR not run for an unprecedented third term.

Harry Truman, elected vice president for FDR’s even more unprecedented fourth term, assumed the presidency on April 12, 1945, when FDR died less than three months after the inauguration. Truman was nominated for president in 1948 and elected, but his contribution to the vice presidency went far deeper than personal success.

Truman took office with a minimum of preparation—FDR had essentially ignored him—and found his plate filled with such items as World War II, the atomic bomb, peace in Europe, and Soviet expansionism. He vowed that no vice president should ever again be so blindsided, and he put his own vice president, Kentucky’s popular Alben Barkley, on the National Security Council and otherwise involved him in government.

From Truman forward, some but not all vice presidents ran as men (and one woman, Geraldine Ferraro) considered capable of occupying the presidency. Is it our bad luck or our good fortune that only one vice president, George H.W. Bush (whose linguistic contribution was “Voodoo Economics”), has made it to the presidency in the last 44 years?