The True Story of Kelly’s Heroes

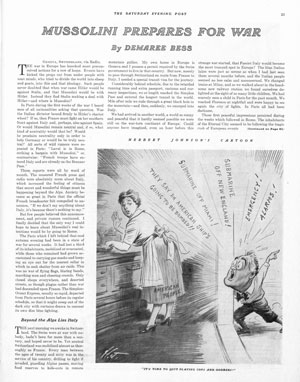

When Kelly’s Heroes hit theatres 50 years ago this week, it came amid a run of incredible success for its star, Clint Eastwood. While the film was not his biggest that year (that would be Two Mules for Sister Sara), it earned mostly positive reviews, recouped its budget, produced a Top 40 hit with the song “Burning Bridges,” and went on enjoy cult status and a place on many lists of the best war films. Most of the negative reviews focused on the uneasy balance between violence and comedy, but Arthur D. Murphy’s dismissal of the film as “preposterous” in Variety is ironic in hindsight. It certainly might seem that the idea of American soldiers in World War II teaming up with German locals to steal gold behind enemy lines is a flight of fancy; the shocking thing is that part is absolutely true.

The trailer for Kelly’s Heroes. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Kelly’s Heroes drew attention from the outset for the obvious reasons, like its cast. Eastwood’s star had been rising steadily for years, coming off of the Sergio Leone “Man with No Name” trilogy, WWII drama Where Eagles Dare, and other Westerns, while the following year would bring him The Beguiled, Play Misty for Me, and his most famous character in Dirty Harry. Kelly’s Heroes co-stars Telly Savalas and Donald Sutherland had both been standouts in The Dirty Dozen; Sutherland had also made a war picture mark in M*A*S*H earlier in the year. Don Rickles was, well, Don Rickles, and Carroll O’Connor was a tireless and familiar character actor one year out from his iconic turn as Archie Bunker.

The plot of the film follows Private Kelly (Eastwood) who discovers the existence of a cache of German gold after capturing a Wehrmacht intelligence officer. He assembles a misfit crew (including Sutherland’s tank squad), and the group makes a sustained effort to find and capture the gold. After fighting their way through a German tank blockade, the soldiers end up making a deal with the last German tank crew to share the gold. The characters split nearly $900,000 apiece and go their separate ways before they’re caught. And yes, something very similar to that actually happened.

The movies theme, Burning Bridges by The Mike Curb Congregation, went Top 40. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Mike Curb Congregation – Topic / Universal Music Group)

Writer Troy Kennedy Martin based the screenplay on an incident that he learned about from, of all places, The Guinness Book of World Records. “The Greatest Robbery on Record,” first listed in 1956 (and holding the spot until 2000), “was of the German National Gold Reserves in Bavaria by a combination of U.S. military personnel and German civilians in 1945.” MGM was so excited by the prospect that their head of production, Elliot Morgan, wrote Guinness for more information. Guinness’s understanding was that more details than that weren’t really available, possibly due to pieces of the story being classified. Martin used the entry as a starting point and wrote the screenplay.

However, the moviemakers weren’t the only intrigued parties. Ian Sayer is a British journalist, entrepreneur, and historian who has led an extremely colorful life. He founded a delivery service that helped pioneer overnight door-to-door delivery on the European continent. His work debunked fake Hitler diaries. And beginning in 1975, he started work on a book that would uncover the true story behind the gold heist.

Sayer’s book with Douglas Botting, Nazi Gold: The Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And Its Aftermath finally saw publication in 1984 (a second version, Nazi Gold: The Sensational Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And the Greatest Criminal Cover-Up, was published in 2012). The books detail that the U.S. Government covered up the theft of millions in Nazi gold from the German National Gold Reserve in Bavaria. The heist was executed by members of the U.S. military cooperating with former German officers, including one-time members of the Wehrmacht and SS. When Sayer sent his information to the U.S. State Department in 1978, it set the wheels turning for an investigation that began in the early 1980s. Eventually, the U.S. recovered two of the gold bars, identified by Nazi-stamped markings, and announced the finding in a press release in 1997. The two bars were valued at over $1 million and eventually found their way to the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold, the body that recovers and redistributes the gold that was seized by the Nazis during the war.

There’s one final twist. In 1984, Sayer spoke to Members of Parliament in an effort to get information about Nazi gold held by the Bank of England. Jeff Rooker, an MP who he had spoken to on the matter, asked Sayer in 1988 to check out an aid fund to ensure that the money was getting to the veterans it was supposed to serve. It turned out that that the citizen who had asked Rooker about the aid fund had been a survivor of the Wormhoudt massacre, when 90 unarmed British troops were killed by the SS in 1940. The officer responsible for the slaughter was SS General Wilhelm Mohnke, who had also guarded Hitler’s bunker and disappeared after World War II. Amazingly, Sayer realized that he’d met Mohnke while researching Nazi Gold without realizing the man’s identity; Sayer informed the authorities, leading to investigations into Mohnke from multiple countries. He was never charged due to insufficient evidence, and lived until 2000.

Today, Kelly’s Heroes is regarded as a classic war film, noted for its ensemble, its humor, and its willingness to show the dark moments of war even among a more lighthearted story. But the story of the film rests atop a much more complex true story, elements of which still remain hidden from view. It’s a good reminder that even as much as we think we know about history, there are always some secrets, and maybe some gold, hidden somewhere.

Featured image: Shutterstock

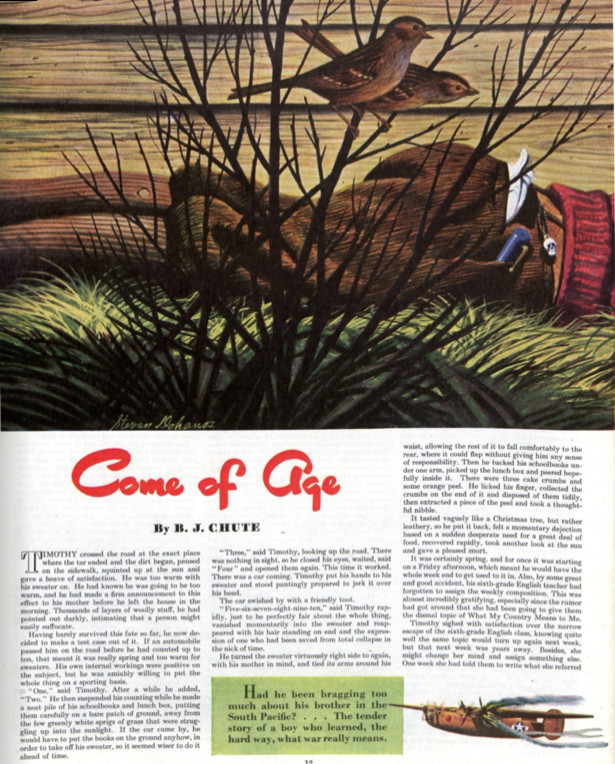

“Come of Age” by B.J. Chute

Writing young adult fiction in Boy’s Life, Child Life, and Boy Scout Magazine, B.J. Chute’s work ranges from fantastical romance to silly farce. In 1944’s “Come of Age,” her short story about a young boy coping with the unimaginable, Chute depicts the innocence of World War II-era America alongside devastating grief in the eyes of a child. As a product of its time, the story gives a snapshot of idyllic family life interrupted by the horror of war.

Published on September 30, 1944

Content Warning: A racial slur

Timothy crossed the road at the exact place where the tar ended and the dirt began, paused on the sidewalk, squinted up at the sun and gave a heave of satisfaction. He was too warm with his sweater on. He had known he was going to be too warm, and he had made a firm announcement to this effect to his mother before he left the house in the morning. Thousands of layers of woolly stuff, he had pointed out darkly, intimating that a person might easily suffocate.

Having barely survived this fate so far, he now decided to make a test case out of it. If an automobile passed him on the road before he had counted up to ten, that meant it was really spring and too warm for sweaters. His own internal workings were positive on the subject, but he was amiably willing to put the whole thing on a sporting basis.

“One,” said Timothy. After a while he added, “Two.” He then suspended his counting while he made a neat pile of his schoolbooks and lunch box, putting them carefully on a bare patch of ground, away from the few greenly white sprigs of grass that were struggling up into the sunlight. If the car came by, he would have to put the books on the ground anyhow, in order to take off his sweater, so it seemed wiser to do it ahead of time.

“Three,” said Timothy, looking up the road. There was nothing in sight, so he closed his eyes, waited, said “Four” and opened them again. This time it worked. There was a car coming. Timothy put his hands to his sweater and stood pantingly prepared to jerk it over his head.

The car swished by with a friendly toot.

“Five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten,” said Timothy rapidly, just to be perfectly fair about the whole thing, vanished momentarily into the sweater and reappeared with his hair standing on end and the expression of one who had been saved from total collapse in the nick of time.

He turned the sweater virtuously right side to again, with his mother in mind, and tied its arms around his waist, allowing the rest of it to fall comfortably to the rear, where it could flap without giving him any sense of responsibility. Then he tucked his schoolbooks under one arm, picked up the lunchbox and peered hopefully inside it. There were three cake crumbs and some orange peel. He licked his finger, collected the crumbs on the end of it and disposed of them tidily, then extracted a piece of the peel and took a thoughtful nibble.

It tasted vaguely like a Christmas tree, but rather leathery, so he put it back, felt a momentary dejection based on a sudden desperate need for a great deal of food, recovered rapidly, took another look at the sun and gave a pleased snort.

It was certainly spring, and for once it was starting on a Friday afternoon, which meant he would have the whole weekend to get used to it in. Also, by some great and good accident, his sixth-grade English teacher had forgotten to assign the weekly composition. This was almost incredibly gratifying, especially since the rumor had got around that she had been going to give them the dismal topic of What My Country Means to Me.

Timothy sighed with satisfaction over the narrow escape of the sixth-grade English class, knowing quite well the same topic would turn up again next week, but that next week was years away. Besides, she might change her mind and assign something else. One week she had told them to write what she referred to as a word portrait, called A Member of My Family. Timothy had enjoyed that richly. He had written, inevitably, about his brother Bricky, and it was the longest composition he had ever achieved in his life. He felt a great pity for his classmates, who didn’t have Bricky to write about, since Bricky was not only the most remarkable person in the world but he was at that moment engaged in being a hero in the South Pacific. He was a pilot with silver wings and a bomber, and Timothy basked luxuriously in the warmth of his glory.

“Yoicks,” said Timothy, addressing the spring and life in general. “Yoicks” was Bricky’s favorite expression.

“Yoicks,” he said again.

He was, at the moment, five blocks from home. The first block he used up in not stepping on the cracks in the sidewalk, which was not the mindless process it appeared to be. He was actually conducting an elaborate reconnaissance program, and the cracks were vital supply lines. By the second block, however, his attitude on supplies had taken a more personal turn, and he spent the distance reflecting that this was the day his mother baked cookies. His imagination carried him willingly up the back steps, through the unlatched screen door and to the cooky jar, but there it gave up for lack of specific information on the type of cookies involved.

Besides, he was now at the third block, and the third block was important, consisting largely of a vacant lot with a run-down little shack lurching sideways in a corner of it. The old brown grass of last autumn and the matted tangle of vines and weeds were showing a faint stirring of greenness like a pale web.

At the edge of the lot, Timothy paused and his whole manner changed. He became alert and his eyes narrowed, shifting from left to right. He was listening intently. The only sound was the peevish chirp of a sparrow; but Timothy was a world away from it. What he was listening for was the warning roar of revved-up motors.

In a moment now, from behind that shack, from beyond those tangled vines, Japanese planes would swarm upward viciously, in squadron attack.

Timothy put down the books and the lunch box, then he stepped back, holding himself steady. His hand moved, fingers curved knowingly, to control and throttle, and from his parted lips there suddenly burst a chattering roar.

The Liberator surged forward gallantly to meet the attackers. Timothy’s face became tense, and he interrupted the engine’s explosive revolutions for a moment to warn himself grimly, “This is it. Watch yourselves, men.” He then nodded soberly. It was a grave responsibility for the pilot, knowing the crew trusted him to see them through.

The pilot, of course, was Bricky. It was Bricky who was holding the plane steady on its course, nerving himself for the final instant of action. The deadly swarm of Zeros swept forward, but the pilot’s face remained impassive.

Z-z-z-zoom, they spread across the sky, their evil advance punctuated by the hail of machine-gun fire. The Liberator climbed, settling back on her tail in instant response to the pilot’s sure hand. As she scaled the clouds, the bright silver of her name, painted along the side, shone defiantly — The Hornet. Bricky had at one time piloted a plane called The Hornet. It was the best name that Timothy knew.

After that, it was short and sharp. A Jap fighter detached itself from the humming swarm. The Hornet rolled and the tail gunner squeezed the triggers. The plane exploded in midair, disintegrated and streamered to earth in flaming wreckage.

“Right on the nose,” said the gunner with satisfaction.

The Hornet had their range now. Zero after Zero fluttered helplessly down out of the sky, dissolving into the earth. The others turned and skittered for their home base, terrified before the invincibility of American man and machine.

A faint smile flickered across the face of The Hornet’s pilot, and he permitted himself a nod of satisfaction. “Good show,” he said.

Timothy sat down on the ground and drew a deep breath. Then he said “Gosh!” and scrambled back to his feet. At home, even now, there might be a letter waiting from Bricky, full of breathless and wonderful details that could be relayed to the fellows at school. A few of them, of course, had brothers of their own in the Air Force, but none of them had Bricky, and that made all the difference. He was quite sorry for them, but most willing to share and to expound.

Gosh, he missed Bricky, but, gosh, it was worth it.

A dream crept across his mind. Maybe the war would last for years. Maybe some one of these days, a new pilot would stand before his commanding officer somewhere in Pacific territory and make a firm salute. “Lieutenant Baker reporting for duty, sir.”

His commanding officer would look up quickly from his notes. “Timothy!” Bricky would say, holding it all back. They would shake hands.

For the entire next block toward home, Timothy shook hands with his brother, but on the last block spring got into his heels and he raced the distance like a lunatic, yelling his jubilee. The porch steps he took in two leaps, crashed happily into the front hall and smacked his books and his lunchbox down on the hall table. He then opened his mouth to shout for his mother, not because he wanted her for anything specific, but because he simply needed to know her exact location.

His mouth, opened to “Hey, mom!” closed suddenly in surprise. His father’s hat was lying on the hall table. There was nothing to prepare him for his father’s hat on the hall table at three-thirty in the afternoon. His father’s hat kept regular hours. An unaccountable sense of formality descended on Timothy. He looked anxiously into the hall mirror and made a gesture toward flattening the top lock of his hair. It sprang up again under his hand, and he compromised on untying the sleeves of his sweater from around his waist and putting it firmly down on top of his books. None of this had anything to do with his father, who maintained strict neutrality on the subject of his son’s appearance. It was entirely a matter between Timothy, the time of day, and that unexpected gray felt hat on the hall table.

There were a dozen reasons for dad’s having come home early. There was nothing to get excited about. Timothy turned his back on the hall table and the hat, opened the door and went through into the living room. There was no one there, but he could hear his father’s voice in the kitchen, and, because the kitchen was a reassuring place, he felt better. He went on into the kitchen, shoving the door only part open and easing himself through it.

His mother was sitting on the kitchen chair beside the kitchen table. She was just sitting there, not doing anything. She never sat anywhere like that, doing nothing.

The formal, pressed-down feeling returned to Timothy and stuck in his throat.

He looked toward his father appealingly, but his father was leaning against the sink, with his hands behind him pressed against it, and staring down at the floor.

“Mom — ” said Timothy.

They both looked at him then, but it was his father who answered. He answered right away, as if it had to be said fast. “You’ll have to know, Tim,” he said, almost roughly. “It’s Bricky. He’s missing in action.” Missing in action. He had met the phrase so many times that it wasn’t frightening. There was no possible connection in his mind between “missing in action” and Bricky …

Missing in action. It was a picture on a movie screen, nothing more. Bricky, the invincible, would have bailed out, perhaps somewhere in the jungle. Or he would have nursed his damaged crate down to earth in a fantastically cool exhibition of flying skill, his men trusting him to see them through.

A hot, fierce pride surged up in Timothy. He wanted to tell his mother and father not to look that way; that Bricky, wherever he was, was safe. He wanted to reassure them, so that they would be smiling at him again and all the old cozy confidence would return to the kitchen.

His father was dragging words out, one by one. “The plane didn’t come back,” he said. “They were on a bombing mission, and they didn’t come back. We just got the telegram.”

An awful thing happened then. Timothy’s mother began to cry. He had never in his life seen her cry. It had never occurred to him that she was capable of it, and a monstrous chasm of insecurity yawned suddenly at his feet.

His father went over to her and got down on his knees on the kitchen linoleum, and he stayed there with his arm around her shoulders, murmuring, with his cheek against her hair, “Don’t, Ellen. Don’t, dearest.”

Timothy stood there in the middle of the floor with his hands jammed stiffly into his pockets and his eyes turned away from his father and mother. He was much more frightened by their sudden unfamiliarity than by what his father had told him. “Missing in action” was just words. His mother crying was a sheer impossibility, made visible before him.

He realized that he had to get out of the kitchen right away, because it was the place he had always been safest, and now that made it unendurable. He couldn’t do anything, anyway. Later, when his mother wasn’t — when his mother felt better, he could explain to her about Bricky being safe. He slid out of the room like a ghost, and, linked in their fear, neither of them even looked up.

In the front hall, he stopped for a moment. The spring sun outside was shining, bright and warm, on the street, and he knew exactly how the heat of it would feel slanting across his shoulders. But his mother had thought he ought to wear his sweater today. He wanted very badly to do something to make her feel better. He frowned and pulled the sweater on over his head, jamming his arms into the sleeves and resisting the temptation to push up the cuffs. It stretched them, his mother said.

He went slowly down the front steps, worrying about his mother. The words “missing in action” still meant exactly nothing to him. They were only another installment in the exciting war serial that was Bricky’s Pacific adventures, and there was not the slightest shadow of doubt in his mind about Bricky’s safe return, though he was eager for details. He guessed none of the other fellows at school had members of their family gallantly missing in action.

No, it wasn’t Bricky that made him feel funny in the pit of his stomach. The thing was he hadn’t known that grownups cried, and the discovery took a good deal of stability out of his world.

His mother might go on being frightened for days ahead, until they heard that Bricky was all right, and he would be tiptoeing around her in his mind all the time to make things better for her, and what he would really be wanting would be for things to be again the way they had been before.

He didn’t want to feel all unsettled inside. The way he felt now was the way he had felt the time they had been waiting to hear from his sister in California when the baby came. He had known quite well that Margaret would be fine and everything, but just the same, the baby’s coming had got into the house and filled it with uncertainties. Now it was the War Department. He was suddenly quite angry with the War Department. Bricky wasn’t going to like it, either, when he got back. He wouldn’t like mom worrying. Timothy wished now he had stayed a little longer in the kitchen and asked a few questions. He would have liked to know what that War Department had said, and, as he went down the street without any particular aim or direction, he turned it over and over in his mind.

He had walked back, without meaning to, to the vacant lot with the old shack on it, and it occurred to him that, while he had been shooting down those Jap planes in Bricky’s Hornet, his mother and father had been there in the kitchen. Looking like that.

He left the sidewalk and walked into the grassy tangle, scuffing his shoes through last autumn’s leaves. He would have liked some company, and he toyed for a moment with going over to Davy Peters’ house and telling him that the War Department had sent them a telegram about Bricky, but decided against it.

He sat down on the grass with his back against the wall of the shack. He could feel the rough coolness of the brown boards even through his sweater, and the sun spilled warmth down his front. It was unthinkable that the shack should ever be more comforting than the kitchen at home, but this time it was.

He wished he knew just what the telegram had said. There was something, he thought, that they always put in. Something about “We regret to inform you,” but maybe that was just for soldiers’ families when the soldier had got killed. He had seen a movie that had that in it once, and it had made quite an impression, because in the movie it was all tied up with not talking about the things you knew, and for days Timothy had gone around with a tightly shut mouth and the look of one who is giving no aid and comfort to the enemy. He had even torn the corners off all Bricky’s letters and burned them up with a fine secret feeling of citizenship, and then he had regretted it afterward, when he remembered it was only the United States APO address and no good to anyone. It was too bad, in a way, because they would have made a good collection. On the other hand, he already had eighteen separate and distinct collections, and the shelf in his room, the corner of the second drawer down in the living room desk, and the excellent location behind the laundry tub in the basement were all getting seriously overcrowded.

He wondered if maybe later he could have the telegram. He could start a good collection with the telegram, he thought. He would print on a piece of paper, “Things Relating to My Brother Bricky,” and paste it onto a box. He even knew the box he would use. It held his father’s golf shoes, but some kind of arrangement could be worked out for putting the shoes somewhere else. His father was very good about that sort of thing, once he understood boxes were really needed, and, later on, this one could hold all the souvenirs and medals and things Bricky would bring home.

The telegram, which maybe began “We regret to inform you,” would fit neatly into the box without having to be folded. It would go on with something about “your son, Lieutenant Ronald Baker,” and then there would be something more, not quite clear in his mind, about “He is reported missing in action over the South Pacific, having failed to return from an important bombing mission.”

Timothy scowled at a sparrow. There was another part that went with the “missing in action” part. Missing, believed — Missing, believed killed.

That was when it hit him. That was the moment when he suddenly realized what had happened — when the thing that the telegram stood for took shape clearly before him, not as something that had frightened his mother and made his father hold her very tight, but as something real about Bricky.

Bricky, his brother. Bricky, with whom he had sat a hundred times in this exact place and talked and talked, Bricky who went fishing with him, who showed him how to tie a sheepshank, who was going to help him build a radio when he came back.

“When he comes back,” said Timothy aloud, licking his lips because they had unaccountably gone dry. But suppose now that Bricky didn’t come back? Suppose that telegram was the end of everything?

It was the vacant lot and the shack that weren’t safe anymore. In the kitchen, he had known, without questioning it, that Bricky was all right. It was here, out in the open, that fear had come crawling. Bricky was dead. He knew Bricky was dead, and he was dead thousands of miles from anywhere, and they wouldn’t see him again ever.

Timothy sat there, and the pain in his stomach wasn’t anything like the pain you got from eating too much or being hungry. He rocked back and forth, not very much, but enough to cradle the sharpness of it, being careful not to breathe, because if he breathed it went down too far inside and hurt too much. If he could just sit there, maybe, not breathing

He couldn’t. There came a time when his lungs took a deep gulp of air without his having anything to do with it, and when that time came there was no way of holding out any longer.

Bricky was dead. He gave a great strangled sob and rolled over on his face, sprawling across the ground, and everything that was good and safe and beautiful quit the earth and left him with nothing to hold on to. He clung to the grass, shaking desperately with fear and pain and loss, and the immensity and the loneliness and the danger of being a human rolled over and over him in drowning waves.

Behind him, the shack, which only a little while ago had been a shelter for the sneak attack of Zero planes, was immobile and solid in the sunshine. It was only a shack in a vacant lot. The tumbled weeds and vines above which The Hornet had swooped and soared were weeds and vines, not a battleground for airborne knights.

It wasn’t that way. It wasn’t that way at all. It had nothing to do with a gallant plane, outnumbered but triumphant. It had nothing to do with the Bricky who had flown in his brother’s dreams, as safe and invincible as Saint George.

A plane was a thing that could be shot down out of the safe sky by murderous gunfire. Bricky was a man whose body could be thrown from the cockpit and spin senselessly down into cold water. It was a cheat. The whole thing was a cheat.

The war — this vague big thing that moved in shadowy headlines, in a glorious pageantry of medals and flags and brave men shaking hands — wasn’t that at all. He had thought it was something like the Holy Grail and King Arthur, that it shone with beauty and was very high and proud.

And it wasn’t. It was fear and this hollowed panic inside him, and it was not seeing Bricky again. Not seeing him again ever. That was why his mother had cried.

That was why his father’s voice had been so rough and quick. And it wasn’t to be endured. He breathed in shivering gasps, there with his face buried in cool-smelling grass and earth and the sun friendly and gentle on his shoulders that didn’t feel it anymore. It would go on like this, day after day and week after week. Bricky was dead, and the place where Bricky had been would never be filled in.

That was what war was, and he knew about it now, and the knowledge was too awful and too immense to be borne. He wanted his mother. He wanted to run to her and to hold to her tightly and to cry his heart out with her arms around his shoulders and her reassuring voice in his ears.

But his mother felt like this, too, and his father. There was no safety anywhere. No one could help him, except himself, and he was eleven years old. He didn’t want to know about all these things. He didn’t want to know what war really was. He wanted it to be a picture on a movie screen again, with excitement and glory and men being brave. Not this immense, unendurable fear and emptiness. He couldn’t even cry.

He was eleven years old, and he lay there face down in the grass, and he couldn’t cry. He groped for anything to ease him, and he thought perhaps Bricky’s plane hadn’t been alone when it crashed to the flat blue water. He thought that other planes might have been blotted out with it — planes with big red suns painted on them.

But even that didn’t do any good. There were men in those planes with the suns on them. Not men like men he knew, not Americans, but real people just the same. No one had told him that he would one day know that the enemy were real people, no one had warned him against finding it out.

He pressed closer against the ground, trying to draw comfort up from it, but he kept shaking. “Now I lay me down to sleep,” said Timothy into the grass. “Now I lay me down to sleep. Now I lay me — ”

It was a long, long time before the shaking stopped. He was surprised, at the end of it, to find that he was still there on the ground. He pushed away from it and sat up, his head swimming. The sun was much lower now, and a little wind had sprung up to move the vines around him so they swayed against the shack. The sweater felt good around his shoulders, and it was the sweater that made him realize suddenly that he couldn’t go on lying there waiting for the world to stop and end the pain.

The world wasn’t going to stop. It was going right on, and Timothy Baker was still in it. He would go on being in it, and the thing inside him would go on being the thing inside him. He would have, somehow, to live with that too. He would have to go back to the house, to the kitchen, to his mother and father, to school, to coming home and knowing that Bricky wouldn’t be there.

Timothy looked around. He felt weak and dizzy, the way he’d felt once after a fever. The shack was there, with no Jap Zeros behind it. The place where he had stood when he was being Bricky and The Hornet was just a piece of ground. His mouth drew in, with his teeth clipping his lower lip, while he stared. There wasn’t any escape. He would have to go back — along the sidewalk, up the path, through the front door, into the hallway, into the living room, into the kitchen. There wasn’t any escape from his mother’s eyes or his father’s voice. He knew all about it now, and he was stiff and sore from knowing about it.

He saw what he had to do. He had to go home and face that telegram. He got to his feet. He brushed off the dry bits of grass that had clung to the blurred wool of his sweater, and he pulled the cuffs around straight, so they wouldn’t be stretched wrong. Then he walked across the grass, out of the lot and onto the sidewalk, holding himself very carefully against the pain.

He held himself that way all the distance back, and when he got to his own front yard he was able to walk quite directly and quickly up the path and up the steps. He turned the doorknob and he went into the front hall. It was getting darker outdoors already, and the hall was dim. It was a moment before he realized that his father was standing in the hallway, waiting for him.

He stopped where he was, getting the pieces of himself together. He wasn’t even shaking now, and some vague kind of pride stirred deep down inside him.

He said, “Dad” dragging the monosyllable out.

“Yes, Timmy.”

“May I see the telegram, please?”

His father reached into his pocket and took out the brown leather wallet that he carried papers around in. The telegram was on top of some letters and bills, and it was strange to see it already so much a part of their living that it was jostled by business things.

Timothy took the yellow envelope and opened it carefully. There it was. “Lieutenant Ronald Baker, missing in action.” The stiff formality of the printed words made it seem so final that he felt the coldness and the fear spreading through him again, the way it had been at the shack. His mind wanted to drag away from the piece of paper, and he had to force it to think instead.

With careful stubbornness, he read the telegram again. It wasn’t really very much that the War Department said — just that the plane had not returned and that the family would be advised of any further news. He read the last part once more. Any further news. That meant the War Department wasn’t sure what had happened. Bricky might have bailed out somewhere. There had been stories in the newspaper about fliers who bailed out and were picked up later. That was a hope. Timothy weighed it carefully in his mind, not letting himself clutch at it, and it was still a hope. It was a perfectly fair one that they were entitled to, he and his father and mother.

He held his thoughts steady on that for a moment, and then he made them go on logically and precisely. Another thing that could have happened was that Bricky had gone down somewhere over land that was held by the Japanese. If that was it, Bricky might be a prisoner of war. Prisoners of war came back. That was another hope, and it was a perfectly fair one too.

He had two hopes, then. They were reasonable hopes, and he had a right to hang on to them very tightly. The telegram didn’t say “believed killed.” Frowning, he went through it in his head again, adding up as if it were an arithmetic problem. There were three things that the telegram could mean. Two of them were on the side of Bricky’s safety, and one was against it. Two chances to one was almost a promise.

Timothy drew a deep breath and handed the telegram back to his father. His father took it without saying anything, then he put his hand against the back of Timothy’s neck and rubbed his fingers up through the stubbly hair. For just a moment, Timothy turned his head, pressing close against the buttons of his father’s coat, then he pulled away.

“Can I go outdoors for a little while?” he said.

“Sure. I guess supper will be the usual time.”

They nodded to each other, then Timothy turned and went out of the house. He went down the steps, his hands jammed in his pockets, and began to walk along the sidewalk, feeling still a little hollow, but perfectly steady.

His heart fitted him again. It had stopped pounding against the cage of his ribs, and it didn’t hurt anymore. The old feeling of safety and comfort was beginning to come back, but now it wasn’t a part of his home or of the day. It was inside himself and solid, so that he couldn’t mislay it again ever. He pushed his hair away from his forehead, letting the wind get at it. The air was cooler now and felt good, and he had a vague moment of being hungry.

Then he looked around him. He was back at the vacant shack, and the shack had been waiting there for him to come. He eyed it gravely. Behind the shack were the Jap Zeros. They had been waiting for him too. He knew they were there and that their force was overwhelming. Timothy’s fingers reached automatically for the controls of his plane. His jaw tightened and his eyes narrowed, and he opened his mouth to let out the roar of motors.

And, suddenly, he stopped. His hand dropped down to his side and his mouth shut. He stood there quite quietly for a moment, as if he had lost something and were trying to remember what it was. Then he gave a sigh of relinquishment.

His fingers curled firmly around air again and closed, but this time they didn’t close on the controls of a machine. They closed on dangling reins.

“Come on, Silver, old boy,” said Timothy softly to the evening. “They’ve got the jump on us, but we can catch them yet.”

He touched his spurs to his gallant pinto pony, and, wheeling, he loped away across the sunlit plain.

Featured image: Illustration by Stevan Dohanos (© SEPS)

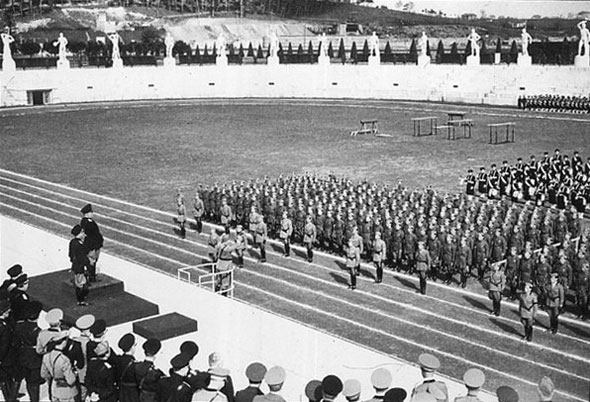

Considering History: Post-9/11 Lessons from America’s Forgotten War in the Philippines

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The effects of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks have defined much of American society over the subsequent two decades. From the creation of new government agencies like the TSA and the Department of Homeland Security (and within it the increasingly visible ICE) to the rise of a ubiquitous surveillance state to countless pop culture texts, 9/11’s influences have been both broad and deep. One of the most significant such effects was also one of the first: the war in Afghanistan, which began on October 7, 2001 as a focused mission to find those responsible for the attacks but evolved into America’s longest war, passing Vietnam for that title in 2010.

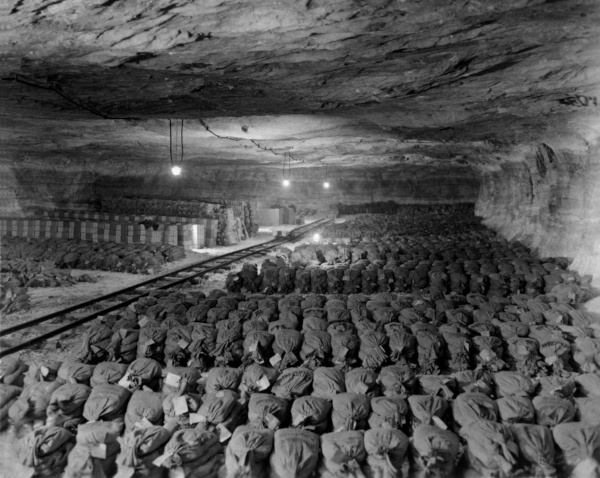

Yet while the conflicts in Afghanistan and Vietnam are indeed two of America’s longest foreign wars, there’s another, far less well-remembered contender for that title: the late 19th and early 20th century war of occupation in the Philippines. That controversial war deserves far more of a presence in our collective memories, for its own sake but also for the lessons it can impart about post-9/11 America.

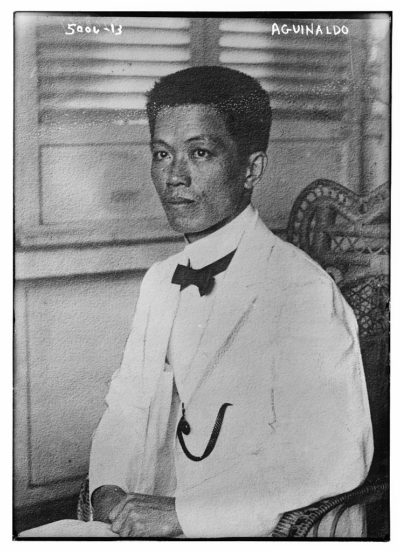

The Philippine-American War emerged directly out of the 1898-99 Spanish-American War, a somewhat more familiar conflict that would likewise be importantly reframed by the war that followed it. After all, the U.S. victory in the Philippines in the Spanish-American War depended on Filipino anti-Spanish revolutionaries, a longstanding group of independence fighters led by the charismatic exile Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy. Much like the CIA worked with the mujahideen (direct predecessors to Al Qaeda and the Taliban) in Afghanistan against the Soviets, the U.S. capitalized on these anti-imperial forces in their opposition to the Spanish in the Philippines.

But Aguinaldo and his fellow revolutionaries had their own goals for their country, ones that preceded U.S. involvement, and they began pursuing them even while the Spanish-American War was still unfolding. After Aguinaldo and his forces defeated the Spanish at the May 1898 Battle of Alapan, he raised for the first time a Filipino flag (sewn in Hong Kong during Aguinaldo’s time in exile there). A few weeks later, Aguinaldo issued a Declaration of Philippine Independence and named himself the first President of the Philippine Republic. The U.S. government refused to acknowledge either those actions or that independent nation, however, setting up an extended conflict once their wartime need for Aguinaldo and his forces ended.

In January 1899, as the Spanish-American War neared its conclusion, President McKinley created a commission (known both as the First Philippine Commission and the Schurman Commission) to investigate conditions in the Philippines and make a recommendation about both the nation’s future and the U.S. role there. But given that the five-member commission featured both Admiral George Dewey (one of the war’s military leaders) and Elwell Otis (the U.S. Military Governor of the Philippines), its conclusions seemed preordained. And indeed, the Schurman Commission came to the conclusion that Filipinos were not ready for independence or self-governance and needed further U.S. presence in the islands to pursue those ends, a perspective that echoes closely the “bringing democracy to the world” narrative that fueled the post-9/11 wars in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

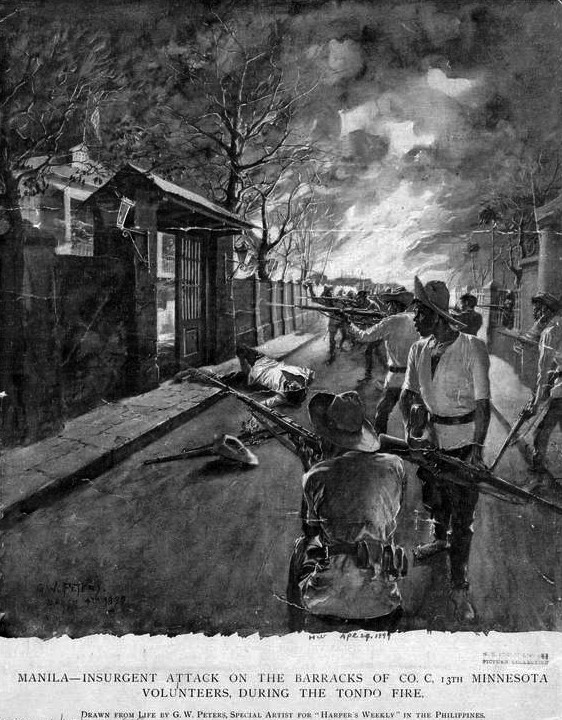

This evolving narrative of the U.S. presence in the islands meant that when the Spanish-American War’s official purpose (liberating the Philippines from Spanish rule) had been achieved, a second, far more extended and bloody war between local forces and occupying U.S. troops commenced. That second conflict began even before the Treaty of Paris between the U.S. and Spain took effect, with the first shots fired between Filipino insurgents and U.S. forces on February 4, 1899 (in what came to be known as the First Battle of Manila), two days before that peace treaty was signed. Many of those Filipino insurgents, like their leader Aguinaldo, had been U.S. allies throughout the war. But just as was the case in Afghanistan and Iraq, as the U.S. forces’ purpose evolved from liberation to occupation, these rebels became obstacles to that ongoing mission.

Thus as was the case in Afghanistan and Iraq, and in Vietnam before them, this became a war of occupation and insurgency, a conflict in which every Filipino was potentially an adversary or at least involved in aiding the revolutionaries fighting against the U.S. forces. That fraught fact meant that every encounter between U.S. troops and Filipino citizens was shadowed by this ongoing conflict, and it concurrently led the U.S. occupying forces to treat all Filipinos as hostile, with destructive effects on both the collective level (such as the destruction of villages) and the individual one (such as the use of torture on perceived enemy combatants, including waterboarding). All of which only pushed more and more Filipinos toward the insurgent cause and reinforced the U.S. as an occupying force in the islands (rather than a liberating presence or a force for democracy).

All those factors contributed to a long, violent conflict between U.S. forces and insurgents. The Philippine-American War officially ended in 1902, but that was just because Aguinaldo had been captured in March 1901 and his allies gradually surrendered over the subsequent months; more than 4,000 U.S. soldiers and more than 20,000 Filipino combatants (and hundreds of thousands of Filipino civilians) died in these first three years of conflict. Filipino insurgents continued fighting U.S. forces in what came to be known as the Moro Rebellion for another decade, only surrendering in 1913. This 15-year war offers vital lessons about what it means to be an occupying force, how a history of realpolitik relationships with revolutionaries can lead to future entanglements, and how a seemingly straightforward military objective can shift through a combination of idealistic and imperialistic factors into a brutal war of occupation and insurgency.

But there are additional lessons from this forgotten long war that are perhaps even more salient for 2019 America. Because of the U.S. occupation, many Filipinos immigrated to America, building on what was already the nation’s oldest Asian-American community but greatly amplifying it in the first decades of the 20th century. These Filipino Americans became hugely significant to every aspect of American society: contributing to the military, like the first Filipino West Point graduate and World War I and World War II hero General Vicente Lim; to civic life, like Agripino Jaucian and the Filipino American Association of Philadelphia, which offered vital medical treatment during the 1918 influenza epidemic; and to activist efforts, like Pablo Manlapit and the ground-breaking Filipino Labor Union in Hawaii.

But this expanding early 20th century Filipino-American community also faced white supremacist xenophobia and prejudice. They were the target of hate crimes and racial terrorism, such as the Watsonville, California “riots” of 1930 in which an entire Filipino-American neighborhood was destroyed. And they were the subject of multiple national exclusionary laws: first redefined as legal “aliens” by the 1934 Tydings-McDuffie Act despite the U.S. occupation of their nation (ironically, the law granted the Philippines eventual independence in order to make that redefinition possible); and then subject to an overt campaign to forcibly remove all 120,000 Filipino Americans back to the Philippines with the 1935 Filipino Repatriation Act.

In 2019, we see many of those same histories playing out when it comes to Arab and Muslim Americans: hate crimes are once more on the rise (as they were in the years after 9/11) against these longstanding American communities; and legal attempts to restrict Muslim immigration are taking place, including ones targeting wartime allies like Afghan and Iraqi military interpreters. These recent events provide one more reason to better remember the histories and legacies of the forgotten Philippine-American War, and to heed the lessons it offers for post-9/11 America.

Featured image: Philippine insurgent soldiers, 1899 (U.S. Army Signal Corps via Wikimedia Commons)

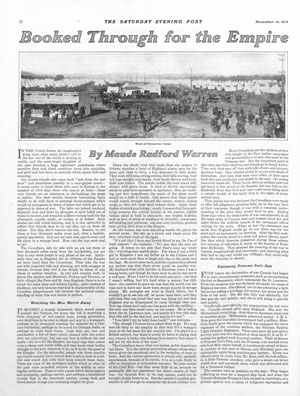

The Heroism of Women in the Boer War

When news came that the Boer women of South Africa were fighting alongside men in their war against the British, the Post applauded.

In war’s long, dreary hours of waiting, the quality of character that can endure quietly represents the very highest bravery that human nature is capable of, and in this greater heroism woman has almost a monopoly.

In their heroism, women are always better than men.

And it’s not only in great things that woman shows her nerve. The other day in Naples, two Boston ladies were leaving a shop. A man seized the purse of one of them, whereupon she took him by the throat, gave him a good shaking, slammed him upon the ground, recovered her property, and then in her cool New England way told him to move on. We can scarcely pick up any newspaper without finding a story of a woman capturing a burglar, stopping a runaway, or doing something of the instant sort that is the very essence of nerve; and we should not forget in this category the Connecticut widow who, although dreadfully afraid of mice, upon finding a lion from Mr. Barnum’s show in one of the stalls of her stable, deliberately whipped the beast away and sent him cowering down the road.

– “The Heroism of Women,” editorial by Lynn Roby Meekins, April 21, 1900.

Featured image: SEPS.

“The Old People” by Ida Alexis Ross Wylie

I.A.R. Wylie spent her childhood on long solo trips bicycling around the English countryside and cruising in Norwegian fjords. The “keen suffragist” published fiction furiously in England and the U.S., and many of her works, like Keeper of the Flame, were adapted into major films. Her 1926 story “The Old People,” set in 19th-century Bavaria, imparts the personal and political aspects of war, as an elderly couple who has lost everything struggles for a meager legacy against a brutal Italian officer.

Published on April 17, 1926

Trumpets. Even Andreas Hofner, who was very deaf, heard them. It was less a sound than a sudden burst of sunlight in the gray winter stillness. The trumpets were blown vigorously but rather unevenly, as though the trumpeters were running, and the faint unsteadiness gave the long blast a thrilling passionate quality, like the break in a human voice. Old Andreas heard it quite distinctly. He looked up from the wooden shield he was carving, absently dusting away some of the delicate shavings that had gathered under his hand, and took off his spectacles as though to listen better.

“Soldiers,” he said aloud.

He stood motionless. In the kitchen next his workshop, Maria, his wife, was clattering busily. He could not hear her, but he knew she was there and he knew that she would be clattering, because it was nearly time for the midday meal. And in the old days, when his hearing had been keen as a hunter’s, he had often smiled to himself, listening to her and thinking how she loved the crisp, clean clatter of her shining copper.

“Maria!” he called in his deep grumbling voice.

But she paid no attention, and he went slowly, with the heaviness of a great strength that has begun to fail, to the inner door. He opened it and the pleasant fragrance that greeted him was like a sound too. It made the fading blue eyes under the thick white brows twinkle. For a moment he forgot what he had wanted to say to her.

“Alterchen, there is something here that smells good.”

“You may well say so,” his wife shouted back cheerfully. “Leberwurst and Spezzel — that’s what it is.”

“Is it a feast day then?” Andreas asked doubtfully.

“Maybe it is. There are so many people on the streets you would think so. Look at them now.”

She pointed a twisted energetic old finger at the window under the smoke-blackened beams, and sure enough the townspeople were moving past in a slow stream. They did not look in as they usually did when they had time to spare. Their faces were grave and anxious, and when Maria Hofner tapped at the panes even Johann Kirsch, who was the Bürgermeister and Andreas’ oldest friend, only nodded hastily and hurried on.

“Perhaps someone has died,” Maria reflected. “But I don’t know who it could be. It is true that Gottfried Baum has had the fever for this last week

“If it had been Gottfried Baum,” Andreas interrupted severely, “I should have been the first to know. The relatives would have sent for me at once. Who else should make his coffin for him? Didn’t he always say, ‘There is no one who can handle wood like Andreas’?”

“It is true, of course,” Maria murmured soothingly. He could not hear her, but he had learned to read her lips.

“It was Gottfried who spoke up for me in the council. He said, ‘No one has a greater claim than Andreas. Andreas lost five sons. And he is the greatest craftsman in Windstättl. He will carve us the finest memorial in the whole of the empire.’”

“They say there isn’t an empire anymore,” Maria broke in. “I don’t understand what they mean, but they say there is no emperor.”

“People chatter a lot of nonsense,” Andreas retorted sternly. “What do the people here know about politics? They hear rumors and they make up fairy tales. If they worked harder they would have more sense.”

He stood watching her, his hand twisted in the short curly white beard that made him look like one of the shepherds that he had carved into the altarpiece for the parish church. These fits of dreaming had grown more frequent of late. While he worked at the memorial he had dreamed — so vividly that once or twice he had looked up and called a name; each time it had been Fritzchen because Fritzchen had been his favorite — and had waited with a thickly beating heart for a door to open. And it took time for him to remember that he was an old man and that Fritzchen and Albert and Kurt and Hans, and even baby Andreas, were all dead.

Maria bustled about. She was the very opposite of her husband. When she had been a girl she had been called the fairy of Windstättl because of her slender figure and tiny hands and feet, and at their marriage the town wits had made jokes about her and Andreas, who could have crushed her with one hand. As a matter of fact, he was very gentle and had never hurt anyone in his life. But all that had changed. The five sons had come and the war had taken them away, and pretty Maria Hofner had become an old misshapen woman, with a bent back and twisted feet that had lost their spring, and a shriveled, hard-bitten little face. But she had plenty of life left. All her movements were quick. She was like a little old sparrow hopping about the dim kitchen.

“Listen!” Andreas commanded.

Maria stopped with the lid of a saucepan in her hand. Yes, there it was again. She had heard it the first time — trumpets. Only this time they sounded nearer and had a harsh, exultant note that hurt the ears.

“Soldiers!”

“There are no soldiers,” Maria protested. “All the soldiers have gone away. Perhaps it is the Schültzenverein making an outing. What day of the year is it, Andreas?”

Andreas Hofner looked at the gaudy calendar that hung by the door. He tore off the forgotten leaves with his thick, strong fingers.

“Saint Hubert’s Day,” he told her.

Maria clucked her satisfaction.

“There then! Of course it’s the Schültzenverein. He’s their patron saint. But why they should make such a noise about it or why anybody should bother about them, goodness knows.”

Andreas went back to his work. Very soon the winter’s light would begin to fail and there was still the lettering to be finished. He had three days left, but his hand had lost something of its steadiness and he had to go slowly. One slip and the work of months might he spoiled. Andreas took the edges of the shield in his hands and bent over it, brooding on each strong, delicate line that for him represented a thought. He had never been outside Windstättl, but he knew in his heart that this was a noble thing that he had made — finer than the altarpiece, finer even than the Christ that from the top of the pass watched over the little town. In a small space Andreas had carved the majesty of the mountains, and at their feet slept a dead Austrian soldier. His face was lifted to the sun that rose just behind the topmost peak of the Königsberg, and even in miniature the peace of its expression was a thing for wonder and pity. Anyone who had known Fritz Hofner would have recognized him.

Fritz and Albert and Kurt and Hans and baby Andreas lay in the crowded military cemetery under the shadow of Königsberg, on whose bitter heights they had fought and died. The place was forlorn and neglected, because the people were too poor even to bring wreaths; and it was Andreas who had cut the simple white crosses and carved in the names and the regimental numbers of the dead heroes. But this was to be their true memorial. On Sunday he would nail it with his own hands to the Rathaus amidst the solemn prayers of the people. So long as the Rathaus stood, Fritz and Albert and Kurt and Hans and baby Andreas would never be forgotten.

Maria came in and stood beside him. A quietness settled about them both, so that they no longer heard the trumpets or the rush of feet. They were alone together. Maria pointed her stiff old finger.

“Für’s Vaterland,” she read aloud. “Ei, that’s got a grand sound to it, Alterchen, and only one more letter left to do.”

He nodded gravely. “It will be finished. I have worked night and day that it should be finished.”

“Ei, but everyone will be pleased when they see it. There isn’t another town in Austria that’ll have such a memorial. It’ll put heart into everyone. When they go past it people will lift their heads again.”

“No one has lost so much,” Andreas said. He said it proudly. Pride had been the only thing that had upheld him. When Fritzchen went — he was the last, swept away with a hundred comrades in an avalanche — the emperor himself had telegraphed. Everyone in Windstättl had seen the telegram. Such a thing had never before happened, and from then onward Andreas and Maria, with their five dead sons, had been set apart.

“There is to be a band,” Maria went on, “and the fire brigade from Eulensee is sending a deputation in uniform, and the bishop is to give the benediction from the Rathaus window. Oh, if they could only see it — the five Buberle — they would be proud too!”

Someone was rattling desperately at the door. Whoever it was was so frightened that they didn’t realize the door wasn’t locked. Maria opened it impatiently. A storm of noise seemed to rush past. There was Elsa, Kurt’s young wife, leaning against the jamb, wide-eyed and panting, her shawl clutched about her and her face grown old.

“Elsa, in Gottes namen what has happened?”

“Haven’t you heard, Mutterle? It’s the Italians — the Italian soldiers. They’ve come over the pass — they’re coming now — hundreds of them!”

She almost screamed, so that her voice sounded like one of the trumpets. The room was full of tumult. It was as though a tidal wave had burst in through the open door and was swirling against the walls, destroying, devastating.

But Andreas held himself steady. He made a proud sweeping gesture with his great arm.

“It’s not true,” he said. “You’re crazy, Elsa, my girl. The war is over. The Italians never came over the Königsberg. We saw to that. Our five sons — ”

Even as he spoke, the Bersaglieri swept past the window. They came at their historic trot, their plumed hats, at a gallant angle, flowing in the gray winter’s wind, their dark intent faces alight, their trumpets shouting.

Andreas strode to the door. “I tell you the war is over,” he said sternly. “It is a mistake. They’ve no right — ”

He was thrust back. The trumpets caught his protest on their hard, shining points of sound and tossed it aside. And Elsa, Kurt’s wife, who was with child, broke into bitter, terrified weeping.

II

The General Beppo Volpi rode with his aide-de-camp down the mountain pass and talked comfortably of old times. The winter’s sun had gone down behind the mountains, and the winding road, still torn by the passage of heavy military traffic, was steeped in cold gray shadow. But the peaks of the Königsberg blazed. The general, wrapped in his wide cloak, pointed at them. Though he was an old man, he had good eyesight; and besides, he knew what he could not see.

“That was my dugout,” he said; “there, on the left where the peak is forked. Twice we lost it and twice we won it back. The last time it came to a hand-to-hand struggle and the place was like a charnel house, so full of dead you could hardly move. And the cold — I shall never forget the cold — never, never. Sometimes I felt like a dead man myself; my limbs wouldn’t move. These mountains, which look so beautiful to you, my dear Strazzi, and over which the tourists will soon be swarming, picking up souvenirs, became to us demons semi-human, monstrous torturers. We cursed them, for every foothold cost us blood and agony. But we held on. If it hadn’t been for the peace we’d have taken this damned little rats’ nest at the point of the bayonet.”

“Doubtless,” the aide murmured politely. “The peace came too soon. We could have taught them a lesson.”

“We shall teach it them yet,” the general said, smiling under his gray mustache.

The two men fell silent. The aide was thinking of Rome, whence he came and which would be enjoying its first festivities since the war. It was hard luck. The prospect of spending the next months in this miserable village made him feel more than ever cold and discouraged. But the general was remembering his youth.

“You Romans don’t understand,” he said presently, as though he had guessed his companion’s thoughts. “I was born in Sedena — Kleinstadt they called it — in Italia Irredenta. We were Italians, every man of us, and we dared not even speak our own tongue. They had their heels on our necks and there was nothing for it but to set our teeth and wait. No, you couldn’t possibly understand what it means to me.”

He was a very handsome old man, very upright, with the fine, aquiline features of his race. But the aide, glancing shyly at him, thought involuntarily of the peaks that were now cold and gray as corpses. There was something deathlike in the implacable figure riding beside him. All very well to play avenger and conqueror, but as for the young aide, he would rather have danced at the Quirinal. He glanced up, however, courteously following his superior’s eyes. Though he had been in the war himself, it was hard to believe that men had actually lived and fought on these sinister and threatening heights.

In the shadow of the mountains, but far back from the road, they passed a walled-in space. In the center was a huge, roughly built cross, and at its feet, nestling like sheep at the feet of a shepherd, were hundreds of little crosses. Very ghostlike they looked in the shrouding twilight. The big cross had not been planted strongly enough to withstand the winter’s storms, and was bowed to one side in an attitude of sorrowful and protecting tenderness.

“Yes,” the general murmured, “we made them pay all right. There were more than that, though. Once a whole company was swept away by an avalanche and were never found. It was like an act of God.”

A chill wind, pregnant with snow, blew down the pass, and the general’s cloak spread out about him like black wings. His companion shivered. It looked very lonely up there in the neglected cemetery lonely and bitterly cold. He could not help imagining the place at night with the snow heaped high over the dead. He had to remind himself that, anyhow, the dead are alone and cold.

Lanterns glimmered ahead of them. They moved hither and thither as though they were afraid and were trying to gain courage from one another. As the two men rode up one of the lanterns advanced alone. It was lifted, showing a man’s stern anxious face. He stood at the general’s knee and tried to speak firmly and with dignity. But his lips quivered.

“Eure Excellenz, I am the Bürgermeister of Windstättl, and in the name of the citizens I protest — ”

The general touched his horse with his spurs so that the startled animal bounded to one side and, the man with the lantern had to scramble into safety. The general spoke loudly so that everyone could hear. His voice was so hard and metallic that it seemed to rise to the very tops of the black and silently witnessing mountains.

“The name of this town is Falzaro. You are Italian citizens.” He bent down from his saddle. “And you, sir, are no longer Bürgermeister.”

He rode on. He carried himself magnificently, as though behind him watched a regiment of his dead comrades. But on the lighted outskirts of the town he looked back.

“They shot my father,” he remarked casually. “You understand — he would not speak their language.” And then he laughed — the aide would have supposed at some light, perhaps rather improper story, had he not seen the old man’s face.

III

They sat together at the long oak table, and though the sentry at the door seemed to take no notice of them, they spoke in undertones. There was the ex-Bürgermeister Johann Kirsch, his brother Georg, the Herr Doktor Menzel, who was very old and kept forgetting what they had come about, and five of the chief tradesmen in Windstättl. Once upon a time they had been prosperous men and had carried their heads high and spoken their minds with robust voices. Now they whispered and kept their eyes down, as though they were afraid of what they might see, or as though they were secretly, tragically ashamed.

The Council Room of the old Rathaus was as familiar to them as their own homes. On winter evenings they had sat under the noble age-blackened beams, shrouding themselves in thick tobacco smoke and arguing comfortably about the town’s affairs, whilst the medieval paintings of saints and horribly tortured martyrs looked down on them with a complacent serenity.

But the room had grown cold. It had a dank, melancholy atmosphere, as though someone had died and lay in invisible state. It smelled of death. The sentry, silent and immobile, might have been on guard at the door of a mortuary. From time to time the eight men glanced at him wonderingly. It was like a dream. Even the noises below in the street had a nightmarish, unfamiliar quality. At any moment they might wake up, blink their eyes and clap the embossed lids of their beer mugs with a great sigh of relief.

“I must have dozed off. I had a devilish queer dream too. I’ll tell you what it was — aber zuerst, nosh eins, meine Herren!”

And they would fill up and lift their mugs with a jovial “Prosit, Alterchen!” whilst the smoke would sink in a kindly veil about them, blotting out that sinister, incredible figure.

Gottfried Keller, the baker, sat back, throwing out his chest and speaking in a loud uncertain voice.

“Na, he certainly doesn’t mind keeping us waiting. But Italians are like that — unpunctual, no system. I remember one time — ”

“Take care!” his neighbor whispered. “Take care, can’t you?”

The sentry glanced around. “Speak Italian,” he ordered curtly, “or hold your tongues!”

They held their tongues for a while, making odd self-conscious grimaces like scolded children. Then they began to whisper again, watching the door out of the corners of their eyes.

“Of course, it can’t be true,” the old Bürgermeister muttered. “What right have they? Even savages commemorate their dead. Still, one doesn’t want to make trouble — ”

The door opened. The sentry saluted smartly. The deputation lumbered to their feet. General Beppo Volpi glanced from one to the other of them with a cold military keenness that was without feeling or human curiosity. Compared to their peasant bluntness, he was like a fine rapier. As he came up to the table he tossed his cloak back, showing the array of ribbons on his breast.

“Well?” he queried. “Well, gentlemen?”

They stammered. Each one of them made a little deprecatory sound, so that it was like a subdued hum. The ex-Bürgermeister began in German and then broke off and started again in rough Italian.

“If you please, it is like this: On Sunday we are to put up a memorial to our dead heroes. It had been arranged before you — ” he made a vague gesture like someone who has been mortally wounded and does not yet know what has happened to him “ — before Your Excellency — in fact before we knew of these changes — of what they had done to us up there. It was to have been a great celebration — a religious celebration, you understand. Our master craftsman has carved a shield which is to hang outside the Rathaus — ”

“The Palazzo Municipale,” General Volpi corrected, throwing down his thick military gloves.

“Ah, yes, of course.” The Bürgermeister ducked his head in docile acknowledgment. “A deputation is being sent from all the surrounding villages and the bishop is to pronounce his blessing from the Rathaus — from the Palazzo window.”

“I have already notified the bishop that the ceremony will not take place.”

They looked at one another. Then it was true. The Bürgermeister began again. He was trying to speak firmly yet quietly, as he had done two nights before on the road. But the military figure, standing at the head of the table, locked in an attitude of static impatience, made him tremble.

“Excellenz, that is what we have heard. But we could not believe it. I would not have taken any notice, but I was afraid — I did not want any misunderstanding. After all, authority is authority. I, as Bürgermeister, understand that — ”

The soldier glanced at him — one sharp, ironical glance, and the speaker faltered. “I mean — I understand — my time of office — I did not want any conflict. I wished to work with you to keep the peace. Since nothing can help us, we wish to do our best. That is why we have come so that the matter should be clear.”

“It is clear.”

The Bürgermeister’s mouth opened. It stayed open and began to tremble oddly, like that of a child on the verge of tears. But the Herr Doktor Menzel nodded and rubbed his hands as though he were congratulating everybody on a satisfactory case. He was very old and hadn’t heard clearly.

“You see,” he chirped — “you see, I told you so. What an unnecessary fuss! In these days we are all civilized, decent people. I told you it would be all right.”

They tried to silence him, tugging him by the sleeve and whispering in his ear. They knew they ought not to have brought him, but he had been on the council for years and had done no harm. Therefore it had seemed cruel to leave him out. Besides, he was a gentleman, a university man, not a rough peasant like themselves, and the general would surely be impressed. But the general measured him with a restrained contempt.

“Perhaps it is time you people understood your position once and for all. By the treaty you have become subject to the Italian Government. Your suggestion that you should celebrate your resistance to our arms is therefore a piece of insolence that you would be wise not to repeat.”

“Excellenza — ”

The soldier brought his fist crashing on the table. “My father was shot by your people for less,” he said. “Now you can go.”

They shuffled their feet. They wanted to go. They were terrified — they hardly knew at what. Something about this iron old man broke them, so that if he had lifted his fist, resting clenched and hard as a block of stone on the table, they would have winced. But the Bürgermeister held his ground desperately.

“Excellenza, it is our dead we honor.”

“Ah, yes, the men who killed our men — my men up there on the Königsberg — my son, for that matter. Excellent! Evidently you have a sense of humor. . . . Now get out of here. You have had my answer. I am in full authority for the time being and you are under martial law. You know, I suppose, what that means.”

“Si, si, Excellenza.”

They ducked obsequiously. But the Bürgermeister had grown suddenly quite calm. It was as though he had come out of terrifying doubt and darkness into some place where he was not afraid because he knew that nothing mattered anymore.

“Forgive me, Excellenza, I don’t think you understand. Our sons died for the fatherland as yours did. It seems they were beaten, but they did their best. They gave all they had. There are no young men left in Windstättl, Excellenza — only us old people. I do not speak of my own sons — I will not speak of myself at all. I think perhaps it is of no great consequence what you and I decide or what happens to us two. In a very few years the dust will be over everything. But there are those in this town who will feel your order, Excellenza, as though it slew their children a second time. I am thinking of old Andreas Hofner and his wife. Excellenza, all their boys went — five in one year. We thought at first they would lose their minds. If they had not felt that their boys had died gloriously, their hearts would surely have broken. Even now they don’t understand and we dare not tell them. For a whole year Andreas has worked at his shield. It is a fine thing, Excellenza — even you would say so — a thing to touch the heart. He is a great craftsman, our Andreas. He carved the crucifix that stands at the head of the pass. Your Excellency must have seen it.”

The general motioned to the sentry. “Get these men out.”

“Excellenza, they are very old, sad people. I dare not tell them. Think — five sons in one year — even the emperor telegraphed. It is only a little thing to allow them — a wooden shield.”

The sentry came with his rifle crossed and began to push them along, hustling them with an emotionless insistence. They went like frightened sheep scrambling for the exit to their pen. But the Bürgermeister stood quietly at his place, his head bent meditatively, and when the sentry touched him he made a stern gesture so that the man involuntarily fell back from him. At the door he turned and bowed to the general, and the General Beppo Volpi, yielding to an instinct stronger than his purpose, touched his cap.

Outside, the deputation huddled together. It was very cold. An icy wind raced down the medieval little street. But it was not the wind that made their teeth chatter. They were unmanned and ashamed. They did not dare speak or look at one another.

It was market day. The street was full of peasants interlaced with carabinieri parading two and two like solemn twin dolls, and smart Italian officers with their caps at a rakish, victorious angle. Amidst so much movement and color, the deputation had a forlorn gray look like a group of prisoners who have been thrust out into the world and no longer know where to turn.

It was Gottfried Keller who said at last, “We must tell them. You will have to tell them, Herr Bürgermeister.”

“I am not Bürgermeister any more, Herr Keller, and I will not tell them.”

“Who will then?”

“God knows, I cannot.” He clenched his hands. “Let them find out for themselves what men are made of,” he added bitterly.

The Herr Doktor Menzel plucked at his sleeve. “Gentlemen, I will tell them. Who has more right to such a task? Didn’t I bring their five sons into the world?”

“Yes, that is true. Let the Herr Doktor tell them.”

They sighed their relief. No doubt it was true that he was a little mad, the Herr Doktor, but he was kind and had skillful hands. He would break Andreas Hofner’s heart and the heart of Maria his wife very, very gently.

IV

He had forgotten. He knew that he had forgotten. For two whole days he had known, and now he stood at the door of Andreas Hofner’s house, plucking his lips with trembling fingers and making little moaning sounds under his breath like someone in torment. It was terrible. He remembered how eager he had been. He had pushed himself forward, determined to show them all that he still counted for something; and they had trusted him, and for an hour or so he had gone about with his head up, feeling resolute and confident again. Then a kind of drowsy mist had settled on his brain and he had forgotten.

Of course he should have gone frankly to Johann Kirsch and told the truth. But he was too ashamed. Once upon a time he had been the cleverest man in Windstättl and people had looked up to him and asked his advice. Now they shook their heads and said, “He forgets, poor old fellow — he forgets everything.” And he could not bear it. He would rather have died than to have gone to them and said, “I have forgotten.”

Everything seemed to combine together to trouble him. The Sunday morning was so still — so very strangely still. It was as though everyone had deserted him. Except for the inevitable carabinieri, who paraded slowly backward and forward, looking about them with puzzled, doubtful eyes, the streets were empty. The windows of the houses had kept their shutters closed. Even the church bells were silent. There was an air of desolate mourning as though the little town covered its face with its hands and wept.

The Herr Doktor did not understand. Perhaps it was the threat of a storm that kept the people hidden. Certainly there was a queer gray light over the Königsberg, whose final peak stood up like a finger against the livid sky. Yes, there was snow coming. But the people of Windstättl were not afraid of snow. He shook his head and rapped timidly. Perhaps when he saw the Hofners everything would come back.

Maria Hofner opened the door to him. At first he was so astonished that he couldn’t speak. Why, she had been married in that dress! Queer that he should remember so vividly something that belonged to forty years back and couldn’t remember what people had said to him only two days ago. But there it was; he remembered every detail. The light embroidered bodice and full flowered skirt, the close-fitting beaded headdress, such as the Windstättl women had worn in the Herr Doktor’s youth, were more familiar to him than his own shrunken hands. But they made her unfamiliarly gnarled and small and twisted. The dress was so new, as though it had been laid out on the bride’s bed only yesterday, and she was so old. For one grisly moment the Herr Doktor thought that the whole of his life had been a dream and that at the touch of some evil magic Andreas Hofner’s pretty wife had withered in her bridal clothes.

He became more confused. He could see that her bright, birdlike eyes were peeping Past him anxiously, right down the street, seeking for someone.

“Na, na, Herr Doktor, it wasn’t you we expected. But nevermind. Come inside, and the others will be along presently.”

“Presently — presently,” the Herr Doktor murmured.

He followed her into the living room. There, too, something had happened — something solemn and touching. The room had been cluttered with life, with a turmoil and struggle of hard-won existence — the birth of children, their tears, their laughter, farewells, unspoken anxiety, crushing grief and stoic silences. Sometimes it had seemed to the old doktor that he could see the ghosts of all the room had witnessed — that the very walls had been impregnated with voices and unheard sighing.

But now the place was empty, swept and garnished as for the coming of some great event. The copper pots and pans gleamed on the walls. The oak table, drawn up in the corner under the crucifix, gleamed like a dark, empty mirror. The clock ticked solemnly. Life had been put away. It was like a church, austere and hushed. And set against the wall, facing the door, as if in welcome, was the carved shield of the Windstättl memorial.

Ah, yes, the memorial. The Herr Doktor remembered now — dimly. Of course. They were to hang the shield today on the wall of the Rathaus. They had been on a deputation to the Italian general about it and the Italian general had said — what had he said? The Herr Doktor groaned secretly. It was as though a gust of wind had blown to the door of his mind, and though he might fling himself against it pitifully, it would not yield. He had to stand outside, shivering and helpless.

But it couldn’t go on. He had to say something. He could see how puzzled they were. The old woman was watching him with her head a little on one side, and he imagined that there was a look on her wizened face as though she knew the thing he couldn’t remember and was afraid. And Andreas himself was watching — waiting for the solemn, tremendous thing to happen.

The Herr Doktor remembered him as a slim handsome young man, but he had grown stout and heavy, and the Tyrolean wedding dress didn’t fit him anymore. He might have been comic — an old man masquerading — but there was an earnest, touching dignity about him. The Herr Doktor had to turn away. He felt dazed and sick with his uncomprehending pity.

“Well, well, that’s fine — that’s fine,” he stammered. “A grand piece of work. Yes, indeed. You must be very proud, Andreas.”

“Are they coming — the others?” Andreas asked. “They were to have been here by now. I was getting anxious. I thought, ‘Suppose there should have been some mistake. Suppose those Italian scoundrels — ’ Why — why do you look like that, Herr Doktor?”

“It is nothing — nothing at all,” the Herr Doktor declared cheerfully. Somebody behind the closed door had whispered to him, but so faintly he couldn’t hear. He went across to the carved shield and ran his shaking hand over its polished surface. “Yes, most beautiful, most touching, as the Herr Bürgermeister said; a thing to move the hardest heart.”

“Did he say that?”

“Indeed he did. . . . Perhaps — perhaps in a moment I shall remember something more.”