Considering History: Voter Suppression and Racial Terrorism, the Twin Pillars of White Supremacy

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

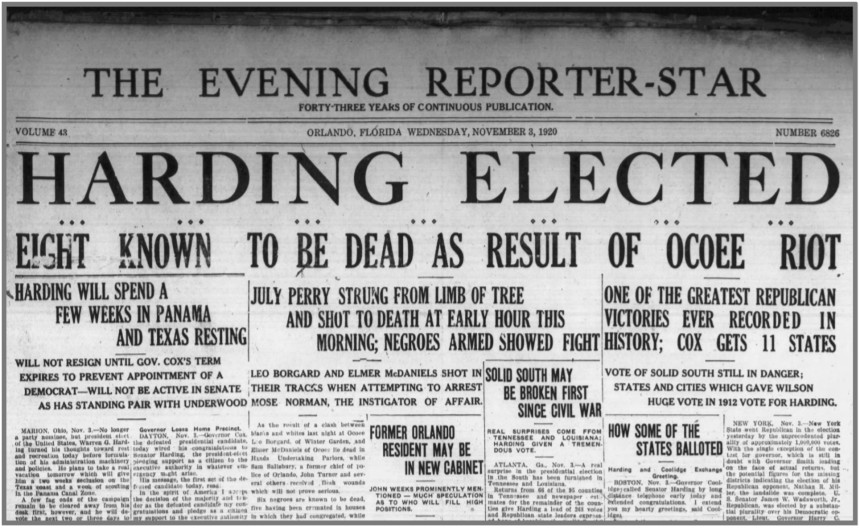

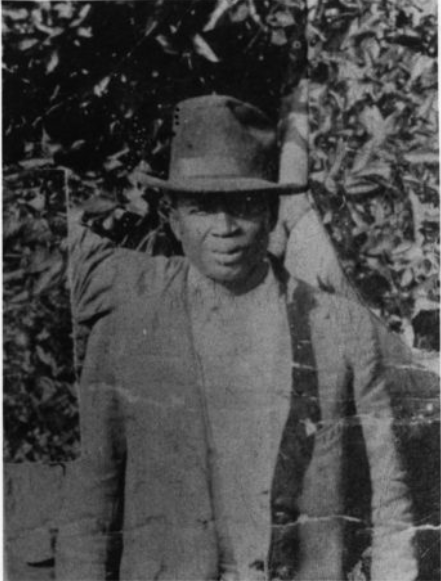

On November 2, 1920, as voters across the country went to the polls to decide a presidential election between two Ohio politicians, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding and Democratic Governor James M. Cox, violence erupted in the Florida town of Ocoee. Local African-American farmer Mose Norman tried to exercise his Constitutional right to vote, and was turned away twice under the pretense of the state’s Jim Crow efforts to disenfranchise black voters. An angry white mob then pursued Norman, laying siege to the home of another man, Julius “July” Perry. Perry fired on the attackers in self-defense, and the mob seized upon that action to terrorize the town’s Black community, eventually killing Perry and more than fifty other African-American residents, burning down homes and businesses, and forcing much of the rest of the community to flee the town.

The Ocoee massacre, known as the “single bloodiest day in modern American political history,” had its roots in multiple historical trends. Like states throughout the Jim Crow South, Florida had developed in the 50 years since the 15th Amendment’s ratification numerous legal measures and social practices intended to make it impossible for African Americans to vote. But those longstanding voter suppression measures were complemented by a much more immediate, violent threat of force: the day before the election, members of the newly resurgent, 2nd Ku Klux Klan had marched through Ocoee, proclaiming through megaphones that “not a single Negro will be permitted to vote.” And no 1920 act of racial terrorism can be separated from the prior year’s epidemic of such violence, the year-long series of lynchings and massacres that came to be called the “Red Summer of 1919.”

Those factors help us understand the divisions and discriminations at the heart of American culture in 1920. But on the 100th anniversary of the Ocoee massacre, and as we approach another election day, that specific historical event can also help us to better recognize an overarching, profoundly relevant American trend: the way in which voter suppression has consistently gone hand in hand with racial terrorism to prop up white supremacy.

In recent years, we’ve started to do a better job of remembering the history of white supremacist racial terrorism in America through such vehicles as public memorials and pop culture texts, including horrific individual events such as the 1921 Tulsa massacre and the century-long lynching epidemic. But too often the stunning brutality and destruction of those acts of violence can make them seem like impromptu explosions, perhaps reflecting consistent undercurrents of racism but not the result of purposeful, extensive, organized political planning.

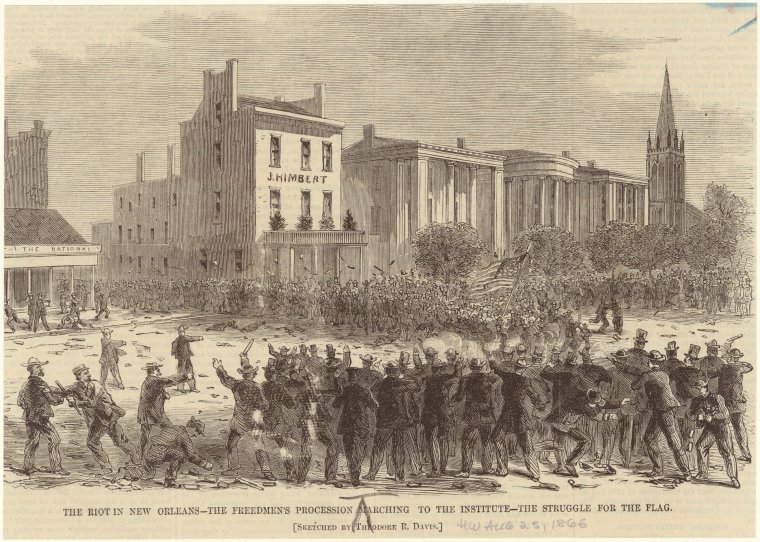

Yet the truth is that these acts of racial terrorism have consistently been tied to planned, organized, systematic plans for voter suppression and related political agendas, as illustrated by not just Ocoee in 1920, but also three prominent 19th century massacres and one from the Civil Rights era. The July 30, 1866 New Orleans massacre began when white supremacists attacked 130 African-American residents marching toward the Louisiana Constitutional Convention at Mechanics’ Institute; the state legislature had passed a series of Black Codes barring Black men from voting (among many other discriminatory effects), and the marchers were hoping to join the Convention to advocate for their rights. New Orleans’ newly re-elected Confederate mayor, John T. Monroe, led a group of ex-Confederates, police officers, and other white supremacists to attack the marchers, starting a massacre that would end with more than 200 African-American Union Army veterans and another 200+ Black civilians killed.

Despite such racial terrorism, African Americans continued to exercise their Constitutional right and active patriotic goal of voting, and were consistently met with extensive suppression and violence. On November 3, 1874, African-American voters at the polls in Eufaula and Spring Hill, towns in Alabama’s Barbour County, were attacked by members of the widespread white supremacist organization The White League; seven African Americans were killed and another 70 wounded. The Barbour County massacre was one of many such events throughout the South on that 1874 election day, a planned campaign of voter suppression and violence after which League-affiliated officials also threw out legitimate votes for Republican candidates and helped install sympathetic Democratic officials in their place (a shift often defined as the beginning of the end of Federal Reconstruction).

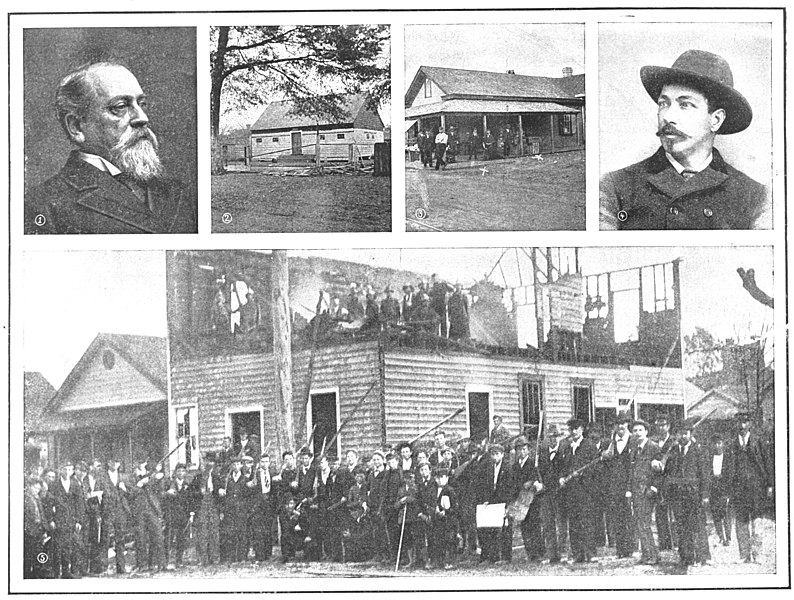

The November 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) coup and massacre originated from even more overtly organized voter suppression goals. By late 1898 Wilmington was one of the last communities in North Carolina (and the entire Jim Crow South) not governed by white supremacists — the so-called “Fusion” Party, featuring African-American political figures and their Republican and Populist white allies, had in the 1896 election held on to many of the city’s positions. White supremacists targeted the next election day, November 8, 1898, as an occasion to reverse that trend by force and violence: planning for months an extensive program of both voter suppression and systemic violence, alongside an accompanying propaganda campaign in the media, that resulted in both a coup d’etat and a massacre that devastated the city’s African-American community.

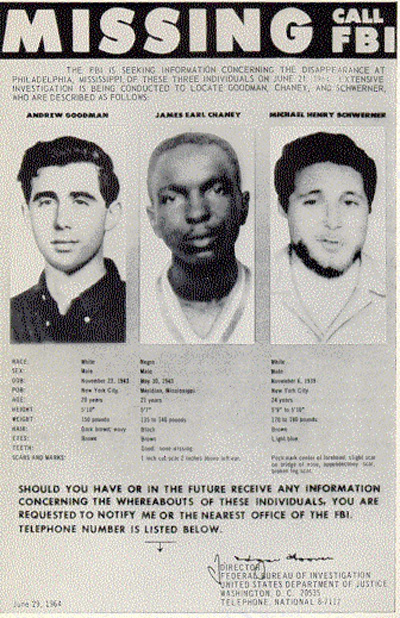

One of the latest documented lynchings, the infamous June 1964 murder of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner near Philadelphia, Mississippi, was similarly interconnected with voter suppression. The three men were working for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as part of its Freedom Summer campaign to register African-American voters in Mississippi and throughout the South, and were on their way to a registration event at a local church when they were pulled over by local law enforcement. An extensive FBI investigation determined that members of the Philadelphia Police Department, the Neshoba county sheriff’s office, and the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan subsequently abducted and killed the men. The collaboration between those official and domestic terrorist organizations doesn’t simply reflect their overlapping membership; it also illustrates that the murder of these voting rights activists was part of a political campaign to suppress African-American votes and keep these white supremacist forces in power.

Throughout American history, those who have fought for the right to vote have had to do so in direct opposition to some of the nation’s most powerful forces, including white supremacist suppression and violence. Those battles continue into the 21st century, and as we continue to fight for and to exercise the right to vote, it’s vital that we remember the foundational and consistent ties between voter suppression and white supremacist racial terrorism.

Featured image: The New Orleans Massacre (Artwork by Theodore R. Davis for Harpers Weekly / Wikimedia Commons)

Considering History: Civil Rights, Racism, and the Question of American Progress

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

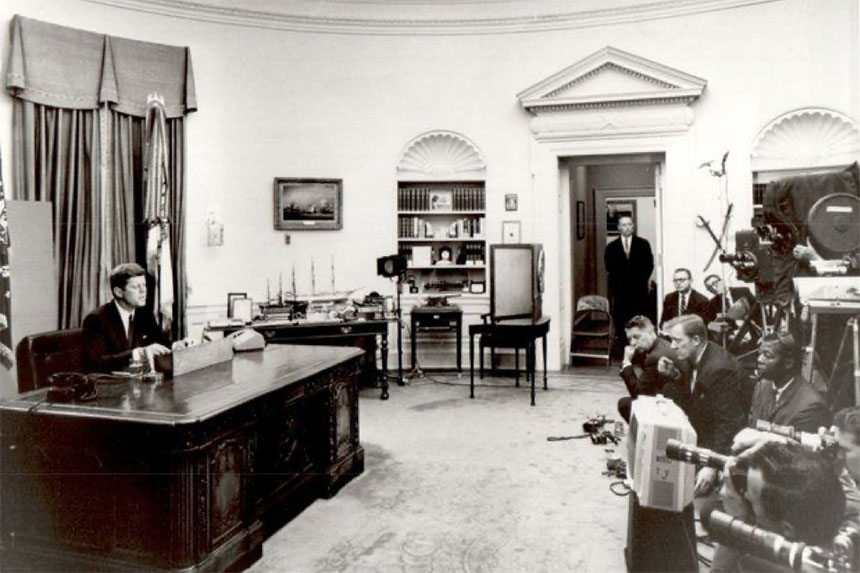

On June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy gave a televised presidential address on the question of race and civil rights. The speech addressed specific, ongoing events: earlier that day Alabama Governor George Wallace had literally blocked two African American students, Vivian Malone and James A. Hood, from enrolling at the University of Alabama; in response Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard, after the arrival of which Wallace backed down and Malone and Hood successfully integrated the university. But Kennedy used his June 11 address and its national platform to go much further than that targeted response, proposing sweeping civil rights legislation that his administration would subsequently send to Congress.

Like Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous March on Washington speech, delivered two-and-a-half months later, Kennedy’s speech frames the events of that time through the fraught question of American progress. As Kennedy notes, “One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free.” In his speech’s opening paragraphs, King extends and deepens that point: “But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free; one hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination; one hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity; one hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.”

A century after the Emancipation Proclamation, America had made painfully little progress on issues of racialdiscrimination, oppression, and violence. But what about now, 57 years after Kennedy’s speech, more than half a century beyond the March on Washington? While some progress has unquestionably been made, when it comes to key issues such as white supremacist violence, voting rights, and structural inequity and inequality, America remains far too close to where it was in the summer of 1963.

The areas on which the most overt progress has been made tend to be those that were directly covered by the Civil Rights Act, the July 1964 law that resulted from Kennedy’s proposal. Institutions like schools and businesses can no longer discriminate against Americans based on their race, nor any other element of their identities (although the legal battle over discrimination based on sexual orientation continues to rage). That progress is about not only access but also equality: institutions can also no longer create separate, segregated spaces for individuals of different races, and must instead offer the same opportunities or face legal and financial penalties; in one of the most famous such cases, In 1994 Denny’s restaurants were proven to be discriminating against African-American patrons and had to pay tens of millions of dollars in settlements.

But as Kennedy’s speech acknowledges, civil rights is about more than just equality of access or opportunity, and instead represents what he calls “a moral issue … as old as the scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution”: “whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated,” whether every American can “enjoy the full and free life which all of us want.” And on a number of levels, African Americans continue to be denied the full protection of the law that would guarantee such freedom from discrimination and oppression.

Protection from racist violence remains frustratingly rare for 21st century African Americans. Some of the foundational incidents of the Civil Rights Movement featured an absence of such protection, from the lynching of Emmett Till and the sham trial that followed it to the ubiquitous sexual violence that precipitated the Montgomery bus boycott. Yet despite civil rights laws and more recent follow-ups like the 2019 anti-lynching legislation, those who commit acts of violence against African Americans still all too often escape justice. Some of those are civilians committing extra-judicial lynchings, like George Zimmerman’s 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin or the two men who killed Ahmaud Arbery in February (and the third who filmed it). But many are officers of the law, such as the police officers involved in the 698 shootings of African Americans between 2017 and March 2020 (22 percent of the 3,215 total shootings over that time; in another 629 shootings the victim’s race was unreported, so the percentage is likely higher still). Many of those citizens and officers were never charged with a crime; of those few who have been indicted, the vast majority were (like George Zimmerman) acquitted on all counts.

One of the principal means through which such legal injustices can be challenged is by voting in new officials, and the Civil Rights Act’s 1965 counterpart, the Voting Rights Act, extended federal voting protections to African Americans. But in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court ruled that key Voting Rights Act protections were unconstitutional, adding that the country “has changed” and that such protections are thus no longer as necessary as they were in 1965. In the half-decade since the decision, that opinion has been proven entirely incorrect, as countless measures have been enacted that work purposefully and effectively to limit and deny the vote for African Americans and other communities of color. The proponents of such measures, which often closely mirror pre-Voting Rights Act practices such as poll taxes and “literary clauses,” have consistently admitted that suppressing the vote among those particular American communities is their goal.

While of course African Americans want the same legal and democratic rights as all Americans, their ultimate goals are even more fundamental and deep-seated: as James Baldwin put it in a 1968 speech, “I simply want to be able to raise my children in peace, and arrive at my own maturity in my own way in peace.” But systemic, structural inequities and inequalities make those goals far less achievable for African Americans than their white fellow citizens. Take two elements of my seemingly progressive home state of Massachusetts, for example. Massachusetts’ public schools are significantly more racially segregated in the 2010s than they were a few decades earlier, with the schools with the highest percentage of students of color receiving over $1000 less in annual funding per pupil. And not coincidentally, a groundbreaking 2017 investigative series by the Boston Globe’s Spotlight team found the median net worth for an African-American family in Boston to be $8 (that’s not a typo, it’s 8 dollars), compared to a median net worth of $247,500 for white families.

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These are the inalienable rights that the Declaration of Independence identifies as core values of the United States of America. In June 1963, the proposed Civil Rights Act (like the Civil Rights Movement) sought to better protect those rights and thus make them more genuinely attainable for African Americans. As of June 2020, it remains an open and crucial question whether the nation has progressed closer to that promise, and what we must do to ensure real progress from here.

Featured image: Lyndon Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act (Wikimedia Commons / LBJ Library / Public Domain)

Considering History: The New Deal, White Supremacy, and How the South Won the Civil War

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On April 9th, 1865, just under four years after the Civil War’s opening salvo at Fort Sumter, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Virginia’s Appomattox Court House, formally ending that divisive and destructive national conflict (although some Confederates refused to surrender for months thereafter). The attempt by 11 Southern states and a few Western territories to create a distinct nation organized around founding principles of slavery and white supremacy, the Confederate States of America (CSA), had failed, and the United States was reconstituted as a unified nation once more.

Yet over the next half-century, as I’ve written about for this column and elsewhere, a neo-Confederate perspective on American history and identity came to dominate the national landscape. A vital new book, historian Heather Cox Richardson’s How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America, links that trend to the development of and battles over the post-Civil War American West. But by the early 20th century a neo-Confederate, white supremacist narrative likewise dominated national politics and policy, as another of this week’s historical anniversaries can help us remember.

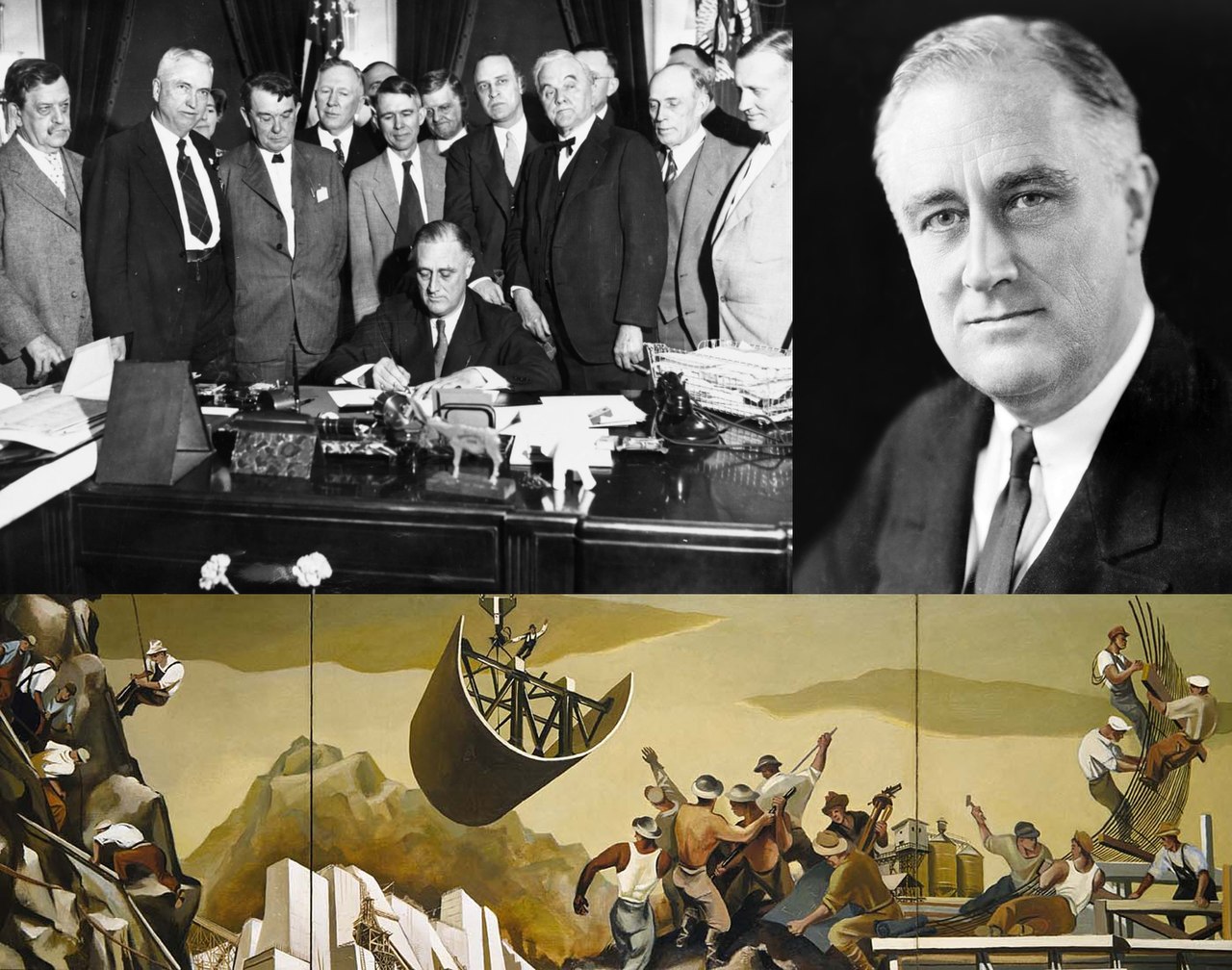

On April 8th, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, a request to Congress for $4.88 billion to create and support a number of public works programs within the overarching frame of the era’s evolving New Deal responses to the Great Depression. Although the Act’s targeted unemployment relief was controversial and much of it was eventually never allocated, the Act did lead directly to the creation of many of the New Deal’s most famous and successful public works programs, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and its subsidiaries such as the Federal Art Project and the Federal Theatre Project, the National Youth Administration, and the Rural Electrification Administration.

Yet the New Deal’s programs, like the Roosevelt Administration overall, consistently gave in to the demands of Southern white supremacists and discriminated against African Americans (and other Americans of color) in a number of distinct yet interconnected ways. Many of those Southern white supremacists were Democratic Congressmen whose votes Roosevelt was courting to secure passage of the New Deal, a political reality for the Democratic Party in this early 20th century period (before the party realignment of the 1950s and ’60s). Yet the very fact that Roosevelt needed those Southern Congressmen’s votes reflects the political and social power of this white supremacist community in 1930s America. And the various forms taken by these New Deal racial discriminations illustrate the destructive effects of white supremacy on millions of Americans.

The most overt such discriminations were the ways in which numerous New Deal programs were crafted to either exclude entirely or limit the opportunities of African Americans. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) excluded the African-American community overtly, refusing to guarantee mortgages for many African Americans seeking to buy homes; the Social Security Act (SSA) did so more indirectly but just as potently, excluding agricultural and domestic workers (two categories in which the majority of African Americans and many other Americans of color worked) from its protections. Other programs discriminated by creating segregated and unequal structures that mirrored Jim Crow systems: the National Recovery Administration (NRA) offered white Americans the first opportunity at its jobs, and paid African American workers substantially less; the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) maintained segregated and significantly less well-maintained camps for African Americans.

The exclusion of agricultural workers from the SSA was paralleled and extended by another, perhaps unintended but still hugely destructive form of discrimination, one exemplified by the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). As created by the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act, the AAA offered farmers subsidies in exchange for limiting their production, a policy intended to limit overproduction and help raise prices. But since many African-American farmers worked as sharecroppers, a system that developed alongside the re-emergence of Southern white supremacy in the late 19th century (part of what historian Douglas Blackmon has called “slavery by another name”), it was their white landlords who received the subsidies, and the farmers who were unable to produce and earn from their crops. The AAA thus pushed more than 100,000 African-American farmers off their land in 1933 and 1934 alone.

Beyond the New Deal’s programs and policies, the Roosevelt Administration likewise appeased white supremacists through its inaction on and even opposition to anti-discrimination laws in the period. The most prominent and ironic example was President Roosevelt’s opposition to an anti-lynching bill on which his wife Eleanor Roosevelt had collaborated with NAACP President Walter White and Congressional allies. Roosevelt told the pair in a private meeting that he could not publicly support the bill, arguing about the Southern white supremacists: “If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass the keep America from collapsing. I just can’t take the risk.” When the bill, known as the Costigan-Wagner Act, nonetheless came before Congress in February 1935, those Southern politicians threatened a lengthy filibuster, and the president remained silent; the bill died without a vote, and no federal anti-lynching legislation would ever be passed (until earlier this year, in a largely symbolic gesture).

The combined effect of all these discriminations and exclusions was that African Americans not only continued to occupy a significantly segregated and disadvantaged position in American society, but also did not receive the same benefits and opportunities from these vital programs as their peers — not during the depths of the Depression, and not over the decades since when many of those programs have continued to aid American communities. In his groundbreaking 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” journalist and public scholar Ta-Nehisi Coates argues that these discriminations (he particularly focuses on housing inequities such as those perpetrated by the Federal Housing Authority) have cost African-American individuals, families, and communities tens of millions of dollars across the 20th century and into the 21st, yet another profound and painful effect to the white supremacist perspective’s powerful hold on American politics and society.

Featured image: An artist’s rendering of the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. (Library of Congress)

Considering History: Charlottesville and the Destructive Effects of White Supremacy

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This week, just before the two-year anniversary of the August 2017 white supremacist and neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, my sons and I will once again drive down for our annual pilgrimage to my hometown. Last August, I used the dual occasions of that anniversary and that trip to write about Charlottesville’s largely hidden histories of Confederate memory and segregation, and how much the 2017 rally echoed those white supremacist legacies. Those lessons are more vital than ever in the summer of 2019.

Yet there are other hidden historical legacies in Charlottesville as well. One of the most pernicious is the longstanding erasure of African-American lives and communities, identities and histories, from both the city’s collective memories and its unfolding story. That erasure comprises one of white supremacy’s most deep and destructive effects, and is painfully relevant today.

One of those long-erased communities were the enslaved African Americans who built and sustained the University of Virginia. Rented enslaved laborers formed a core community during the university’s 1817-1825 construction, with the university paying more than $1,000 in hiring fees (more than $21,000 in contemporary value) to slave owners at the 1820-1821 height of activity. The 800,000-900,000 bricks used to construct the Rotunda, the university’s most famous structure, were manufactured by a group of 15 slaves in 1825. Once the university opened in 1825, enslaved men and women worked in numerous roles to keep it running, with an average of more than 100 enslaved laborers performing housekeeping, culinary, and personal service duties (such as blacking students’ shoes) throughout the pre-Civil War decades.

These enslaved men and women were also the frequent target of abuse and violence from the university’s elite male students. In November 1837, a group of drunken students beat the university bell-ringer, Lewis Commodore; just a few months later, in February 1838, two students savagely beat Fielding, a slave owned by mathematics professor Charles Bonnycastle, and the professor had to intervene “for the purpose of preventing his servant from being murdered.” In April 1850, three students abducted and raped a 17-year-old enslaved girl from Charlottesville; six years later, in 1856, student Noble Noland beat a 10- or 11-year-old enslaved girl unconscious because, he told the Faculty Committee, she had been “insolent to him” and such a beating was “not only tolerated by society, but with proper qualifications may be defended on the ground of the necessity of maintaining due subordination in this class of persons.” Noland, like many of these attackers, went unpunished.

For nearly two centuries, neither the University of Virginia nor the city of Charlottesville acknowledged this history of slavery and racism in any consistent public fashion. Much as Thomas Jefferson’s individual status as a slave owner was largely elided, (enslaved African Americans were frequently referred to as “servants” on tours of Monticello until the early 21st century), so too did narratives of Jefferson’s “academical village” highlight the space’s ideals and minimize (at best) the historical oppression on which it was literally built. Efforts are finally underway to redress those absences, including both the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University and a memorial to a cemetery for enslaved laborers. That cemetery had gone unmarked for more than 150 years, a telling reminder of both how fully this community had been buried and how much work remains to be done.

The destruction and burial of African American communities in Charlottesville continued long after the abolition of slavery, and indeed well into the 20th century. Over the course of the century’s early decades, the Vinegar Hill neighborhood, located between the city’s downtown shopping district and the university grounds, became one of Charlottesville’s most prominent African-American communities, featuring 140 homes, 30 black-owned businesses (everything from a jazz club to a fish market), and a church. As with so many African-American neighborhoods throughout the Jim Crow South (and an increasingly segregated nation), Vinegar Hill came to embody both the civic spaces into which African-American communities were forced and the resilience, solidarity, and power with which those communities responded.

Through a series of 1950s and 1960s efforts, however, Charlottesville demolished that neighborhood in the name of “urban renewal.” In January 1954 the City Council adopted a resolution critiquing the city’s large number of “unsanitary and unsafe inhabited dwelling accommodations”; after a very narrowly decided referendum vote, in June of that year the city established a Housing Authority to address this perceived problem. Over the next few years, that agency focused its attention on plans for “redeveloping” the Vinegar Hill neighborhood, which, as one supportive newspaper editorial put it, “is related closely with the rest of the downtown Charlottesville area which seriously needs room for expansion.” Expansion, redevelopment, renewal — these were all euphemisms for the unnecessary, overtly white supremacist displacement of a thriving African-American neighborhood.

In 1960, the Housing Authority proposed a referendum in support of “redeveloping” Vinegar Hill. Most of the city’s African-American residents could not vote in that referendum, thanks to a longstanding, racist poll tax. On June 14, 1960, the referendum narrowly passed, and by 1964 a plan was in place to bulldoze the entire neighborhood. Despite sustained opposition from African-American residents and their allies, in 1965 the neighborhood was razed, and most of its residents displaced to the city’s newly constructed Westhaven public housing project. Federal law required that the city provide such housing for residents it was displacing, although of course a unit in a project is no equivalent to a single-family home. Moreover, Westhaven was apparently as shoddily constructed as many of the era’s public housing projects, and by the 1980s many of its buildings were deteriorating.

Physician Mindy Thompson Fullilove has coined the term “root shock” to describe “the consequences of African American dispossession.” That shock, like the dispossession and destruction that cause it, is a purposeful and indeed central goal of white supremacy: to not only uproot American communities of color, but to make it impossible for those communities to endure as part of the civic life of cities and of the United States. Erased from both the landscape and memory, absent from both narratives of the past and visions of shared futures, these communities would too often, as Fullilove traces, experience “a profound shift in [their] political and social engagement” with both their local worlds and the nation.

That’s the crucial, tragic irony of white supremacist, exclusionary visions of America — in service of a mythic definition of a homogenous nation that never was, they seek to destroy the thriving, inclusive communities that truly define our shared identity. As I argue throughout my new book, We the People: The 500-Year Battle over Who is American, countering those exclusions requires acknowledging the communities and histories that exemplify an inclusive America. On the two-year anniversary of the Charlottesville white supremacist rally, remembering both enslaved laborers and the Vinegar Hill neighborhood would be a fitting response indeed.

Featured image: White supremacists clash with police in Charlottesville, VA, on August 12, 2017 (Evan Nesterak, Wikimedia Commons, via the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)