How Dodge City Became The Ultimate Wild West

Everywhere American popular culture has penetrated, people use the phrase “Get out of Dodge” or “Gettin’ outta Dodge” when referring to some dangerous or threatening or generally unpleasant situation. The metaphor is thought to have originated among U.S. troops during the Vietnam War, but it anchors the idea that early Dodge City, Kansas, was an epic, world-class theater of interpersonal violence and civic disorder.

Consider this passage from the 2013 British crime novel Missing in Malmö by Torquil MacLeod: “The drive to Carlisle took about 25 minutes. The ancient city had seen its fair share of violent history over the centuries as warring Scots and English families had clashed. The whole Border area between the two fractious countries had been like the American Wild West, and Carlisle was the Dodge City of the Middle Ages.”

So, just how bad was Dodge, really, and why do we remember it that way?

“A gentleman wishing to go from Wichita to Dodge City, applied to a friend for a letter of introduction. He was handed a double-barreled shotgun and a Colt’s revolver.”

The story begins in 1872, when a miscellaneous collection of a dozen male pioneers — six of them immigrants — founded Dodge astride the newly laid tracks of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. The town’s early years as a major shipping center for buffalo hides, its longer period as a “cowboy town” serving the cattle trails from Texas, and its easy accessibility by rail to tourists and newspaper reporters made Dodge famous. For 14 years, the media embellished the town’s belligerence and bedlam — both genuine and created — to produce the iconic Dodge City that was, and remains, a cultural metaphor for violence and anarchy in a celebrated Old West.

Newspapers in the 1870s crafted Dodge City’s reputation as a major theater of frontier disorder by centering attention on the town’s single year of living dangerously, which lasted from July 1872 to July 1873. As an unorganized village, Dodge then lacked judicial and law-enforcement structures. A documented 18 men died from gunshot wounds, and newspapers identified nearly half again that number as wounded.

But the newspapers didn’t merely report that news: They interwove it with myths and metaphors of the West that had emerged in the mid-century writings of Western travelers such as Frederick Law Olmsted, Albert D. Richardson, Horace Greeley, and Mark Twain, and in the “genteel” Western fiction of Bret Harte and its working-class counterpart, the popular yellow-back novels featuring cowboys, Indians, and outlaws.

Consequently, headlines about seriously lethal doings in Dodge echoed the make-believe West: “BORDER PASTIMES. THREE MEN BORED WITH BULLETS AND THROWN INTO THE STREET”; “FROLICS ON THE FRONTIER. VIGILANTES AMUSING THEMSELVES IN THE SOUTHWEST … SIXTEEN BODIES TO START A GRAVEYARD AT DODGE CITY”; “TERRIBLE TIMES ON THE BORDER. HOW THINGS ARE DONE OUT WEST.”

One visiting reporter remarked that “The Kansas papers are inclined to make mouths at Dodge, because she has existed only one month or thereabouts and already has a cemetery started without the importation of corpses.” Another quipped, “Only two men killed at Dodge City last week.” A joke circulated among Kansas weeklies: “A gentleman wishing to go from Wichita to Dodge City, applied to a friend for a letter of introduction. He was handed a double-barreled shot-gun and a Colt’s revolver.”

The bad news out of Dodge made its major East Coast debut in 10 column inches in the nation’s then most prestigious newspaper, the late Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Titled “THE DIVERSIONS OF DODGE CITY,” it condemned the village for the lynching of a black entrepreneur. “The fact is that in charming Dodge City there is no law,” it concluded. “There are no sheriffs and no constables. … Consequently there are a dozen well-developed murderers walking unmolested about Dodge City doing as they please.”

Conditions of well-publicized anarchy, though they sold out-of-town papers, were not what Dodge City’s business and professional men wanted. From the town’s founding they had feared more for their pocketbooks than for their lives. Their investments in buildings and goods, to say nothing of the settlement’s future as a collective real-estate venture, stood at risk. For their common business enterprise to pay off, they had to attract aspiring middle-class newcomers like themselves.

And so, in the summer of 1873, Dodge’s economic elite wrested control of the situation. The General Land Office in Washington at last approved its group title to the town’s land, and the electorate chose a slate of county officers, of whom the most important was a sheriff. Two years later, Kansas granted Dodge municipal status, authorizing it to hire a city marshal and as many assistant lawmen as needed.

From August 1873 through 1875, apparently no violent deaths occurred, and from early 1876 through 1886 (Dodge’s cattle-trading period and during its ban on the open carry of sidearms), the known body count averaged less than two violent deaths per year, hardly shocking. Still, the cultural influence of that infamous first year has colored perceptions of the settlement’s frontier days ever since. Part of the reason was a Swedish immigrant, Harry Gryden, who arrived in Dodge City in 1876, established a law practice, inserted himself into the local sporting crowd, and within two years began penning sensationalist articles about the town for the nation’s leading men’s magazine, New York’s National Police Gazette, known as the “barbershop bible.”

In 1883, a Dodge City reform faction briefly assumed control at City Hall and threatened to start a shooting war with professional gamblers. Alarmist dispatches, including some by Gryden, circulated as Associated Press stories in at least 44 newspapers from Sacramento to New York City. The Kansas governor was preparing to send in the state militia when Wyatt Earp, arriving from Colorado, brokered a peace before anyone got shot. Gryden, having already introduced both Earp and his friend Bat Masterson to a national readership, penned a colorful wrap-up for the Police Gazette.

With the end of the cattle trade at Dodge in 1886, its middle-class citizenry hoped that its bad reputation would at last subside. But interest in the town’s colorful history never disappeared. This enduring attention eventually led to Dodge’s inauguration in 1902 as a staple item in the upscale mass-circulation magazines of the new century, including the very widely read Saturday Evening Post.

With that, the dangers of Dodge became a permanent commodity — a cultural production that was retailed to a primary market of tourists, and wholesaled to readers and viewers. Thereafter, writers catering to the public’s fascination with the town’s violent reputation seemingly tried to outdo one another in lurid generalizations: “In Dodge … the revolver was the only sign of law and order that could command respect.” And: “The court of last resort there was presided over by Judge Lynch.” And: “When one was ‘bumped off,’ the authorities just hustled the body out to Boot Hill and speculated upon what else the day would bring forth in bloodshed.”

Dodge’s local handful of yarn-spinners endorsed such nonsense, and bogus estimates of those interred on Boot Hill ranged from 81 to more than 200. By the 1930s, the town’s consensus had settled on 33, a number that included victims of illness as well as violence — but a best-selling biography of Wyatt Earp, published in 1931 by the California writer Stuart Lake and still in print, boosted the body count back up to 70 or 80. Lake’s book’s success, a burgeoning auto-borne tourism, and the Great Depression’s severe economic effect on southwest Kansas collaborated in wiping out any remaining local resistance to memorializing Dodge City’s bygone days.

Writers catering to the public’s fascination with the town’s violent reputation seemingly tried to outdo one another in lurid generalizations.

Movies and then television also got into the act. As early as 1914, Hollywood had discovered the old frontier town. In 1939 Dodge got major film treatment. But it was a TV series set in Dodge that ensured its continuing cultural importance. Gunsmoke entertained literally millions of Americans for a phenomenal 20 years (1955-1975), becoming one of the longest-running prime-time serials ever aired. Ironically, because the hour-long weekly program appears to have prompted the “Get outta Dodge” trope, the population of Hollywood’s Dodge was an interesting soap-opera collaborative of reasonable citizens beset with weekly onslaughts of assorted trouble-making outsiders. It was a dangerous place only because of the people who did not live there.

Imaginary Dodge is still hard at work helping Americans chart their moral landscape as the archetypal bad civic example. Inserted into the national narrative, it promotes belief that things can never be as dreadful as they were in the Old West, thereby confirming that we Americans have evolved into a civilized society. As it reassures the American psyche, the Dodge City of myth and metaphor also incites it to celebrate a frontier past brimming with aggression and murderous self-defense.

Originally published at Zócalo Public Square. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

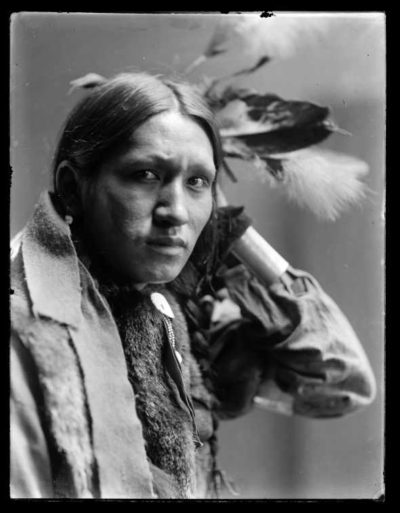

Intimate Portraits of American Indians

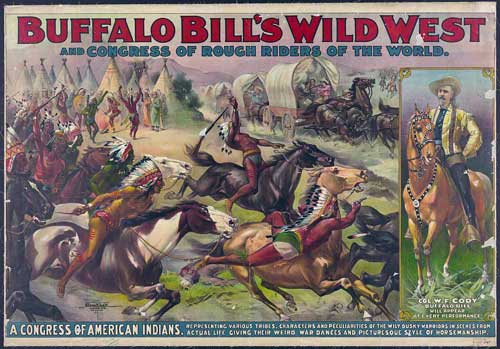

In 1898, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody led a spectacular parade down Fifth Avenue in New York. A troupe of hundreds of performers — American Indians in traditional headdresses, cowboys in 10-gallon hats, and military men from Europe, the Middle East, and other countries who were known as the Congress of Rough Riders of the World in colorful regalia — marched down the broad avenue, accompanied by hundreds of horses, buffalo, and other animals.

The parade was designed to entice the public to attend performances of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which played across the country and Europe in grand outdoor arenas holding as many as 10,000 to 20,000 ticket holders. Between 1883 and 1913, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West toured every year from April through October, preparing a full program of entertainment: feats of horsemanship, marksmanship, and reenactments of Custer’s Last Stand at the Battle of Little Big Horn, the Battle of Summit Springs, the Deadwood Stagecoach robbery, and an “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin.”

Cody and his partners marketed the Wild West program as an educational exhibition and experience, introducing audiences to the American frontier and cowboy life, American Indians, and later, internationally acclaimed military and equestrian teams. Ticketed patrons could visit the Wild West village, the camp where Cody and all of his performers lived at each tour stop.

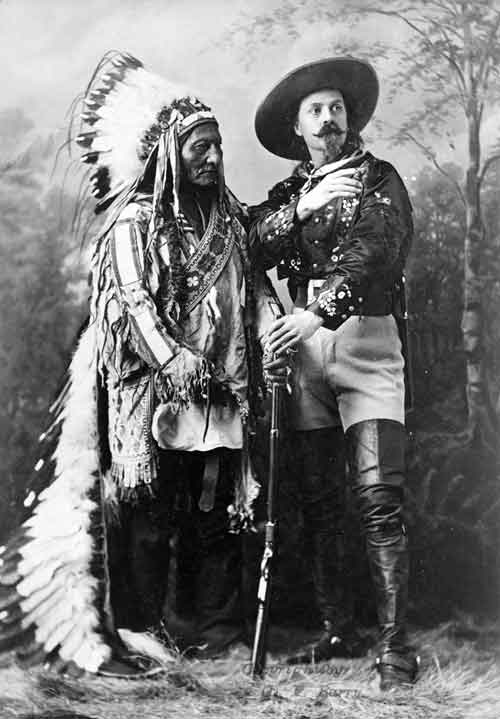

Cody befriended many of the American Indian men performing with his Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, but the daily programs depicted American Indians in the most stereotypical of situations, relentlessly attacking white American settlers or soldiers.

Gallery

Photo by Gertrude Kåsebier.

Photo by Gertrude Kåsebier.

Photo by Gertrude Kåsebier.

Photo by Gertrude Kåsebier.

Photo by Gertrude Kåsebier.

To read the entire article from this and other issues, subscribe to The Saturday Evening Post.

America’s First Superstar: William Cody (AKA Buffalo Bill) and his Wild West

There had never been a celebrity like him. At the height of his popularity, William F. Cody was probably the most recognized man on earth. He received the adulation normally reserved for kings and presidents. And he became the idol of a generation through thousands of appearances in his own extravaganza: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.

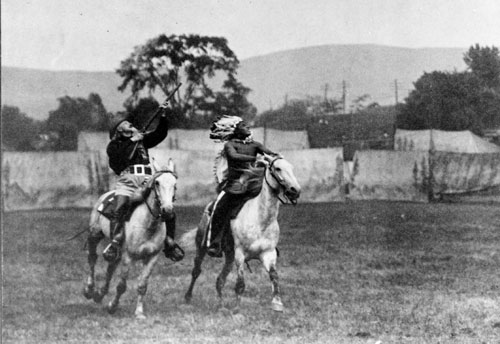

The show was as unique as the man. Far more than a circus or rodeo, his 1,000-member troupe featured exhibitions by talented riders and marksmen of the west. A typical show would include trick riding and races between cowboys as well as Native Americans. One of the big stars was the diminutive (4’11”) Annie Oakley who, shooting at a distance of 30 paces, could split playing cards edge-wise, hit dimes tossed in the air, or knock a cigarette from the lips of her husband.

The show also included western melodramas that mixed historical fact and fiction, like the re-enactment of Custer’s last stand, in which a regiment of cowboys dressed as soldiers were defeated by Indian riders. After the last man has fallen, Cody and his men would ride onto the scene too late to save Custer or his men. Next came the re-enactment of Cody’s shooting and scalping of the Cheyenne warrior Yellow Hand—a true occurrence—which was presented as his revenge for Custer. The final number was an attack by Native American horsemen on the cabin of a pioneer family. In this case, Buffalo Bill and his men arrived in time to drive off the Indians and save the white settlers.

Source: Library of Congress

The secret to the show’s remarkable success and long run—from 1883 to 1906—was Cody himself. He was more than a skilled marksman and horseman, he was the real thing—a true hero of the old west.

At the age of 11, he was working as a rider for a wagon train. Over the years, he found work as buffalo hunter, pony-express rider, trapper, prospector, and Army scout (which is how he earned the Medal of Honor).

In 1869, he came to the public’s attention when writer Ned Buntline made him the hero of one of his dime novels Buffalo Bill, The King of the Border Men. The book became a successful play. When Buntline wrote a second Cody play, Scout of the West, Cody agreed to play the lead, and for the next ten years, he appeared before the public as a theatrical version of himself.

During this time years, it appears Cody tried to copy Buntline’s success by writing a novel of his own. Prairie Prince, The Boy Outlaw; or, Trailed to His Doom, appeared in our October 16, 1875 issue.

The story opens with a young woman…

“A maiden upon whose sunny head but fifteen summer suns have shone.” She is wandering the prairie, stalked by a pair of hungry wolves. She is saved at the last minute by “a mere lad… tall in stature, well formed, with broad, square shoulders, small waist, and limbs of which an Apollo might well have been proud, while his every movement was graceful” etc.

When the young lady’s father, Major Racine, asks the identity of his daughter’s rescuer, an orderly says, “It is the Prairie Prince, sir.”

“No!” exclaims the Major. “Can this be that daring boy whose wonderful deeds have gone along the whole border, and have gained him the name of the Prairie Prince?” And Major Racine gazed with a strange interest into the boy’s face, while the soldiers crowded around and bent upon him looks of admiration and respect. Quietly, and with a proud smile upon his lip, the youth sat his horse, his clear, piercing eyes meeting the gaze of the military commander” etc.

The authorship is debatable. “Prairie Prince” might have been Cody’s own novel, or something Ned Buntline wrote under Cody’s name. If it was Cody’s work, he was smart not to make writing his future.

Source: Library of Congress

After a decade of playing someone else’s version of Buffalo Bill, Cody decided to present his own version of the character. On May 1, 1883, he premiered his Wild West show, appearing with a troupe of veteran cowhands and Indian riders from the Sioux tribe.

Up to that time, much of America’s entertainment was based on European styles and traditions. But Cody introduced the country to something wholly American. It was new, exciting, and home-grown.

A year after the Wild West opened, Cody received a letter from Mark Twain who praised the show–“It brought vividly back the breezy wild life of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, and stirred me like a war-song”–and encouraged Cody to take his “purely and distinctively American” show to Europe.

Three years later, Cody followed Twain’s advice. The Wild West troupe arrived in Great Britain in time for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Over the next four months, over 2.5 million Britons watched Cody’s spectacle and formed a general impression of Americans from this extraordinary showman.

He wasn’t a bad representative of his countrymen. He was well-mannered, good-looking, and could skillfully handle a gun and a horse. And he was highly representative of Americans in his attitude toward the modern age. He regarded the past with a conflicted, sentimental perspective; he liked progress but hated the cost. He celebrated the white settlement of the west but regretted what it had destroyed.

His ambivalence can be seen in “Hunting Down the Buffalo,” which he wrote for the Post on July 15, 1899. “As late as 1869, General Sherman reported nine million buffaloes on the prairies, and this was a conservative estimate. Ten years later these vast herds were completely wiped out—a whole division of the animal kingdom stung to death by the bullets of wasteful professional hunters, who left millions of pounds of fine meat rotting in the sun.”

He assured Post readers that the slaughter was necessary: “It was a sharp, quick way of ridding the plains of a cumbrance that had to give place to a wiser use of these fine grazing lands. It was another instance of civilization getting what it wanted and never minding the cost.” It is a curious attitude for a man who earned his reputation and nickname for killing buffalo.

In the article, he drew a parallel between the fate of the buffalo and the Native American. “We could not make useful citizens of the Indian, and we could not run our brands on the buffalo, so now there are few Indians and no buffaloes.” Both, he believed, had fallen victim to the greed of white settlers.

His audience might not have shared this conclusion, but they were applauding it when they watched his show. His fair-minded attitude was part of the appeal of the Wild West. Like most superstars, his success came from an ability to see a little farther down the road than his audience.