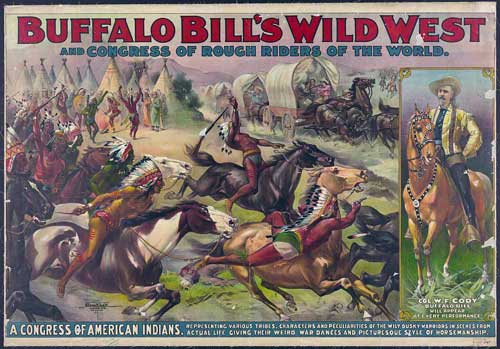

There had never been a celebrity like him. At the height of his popularity, William F. Cody was probably the most recognized man on earth. He received the adulation normally reserved for kings and presidents. And he became the idol of a generation through thousands of appearances in his own extravaganza: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.

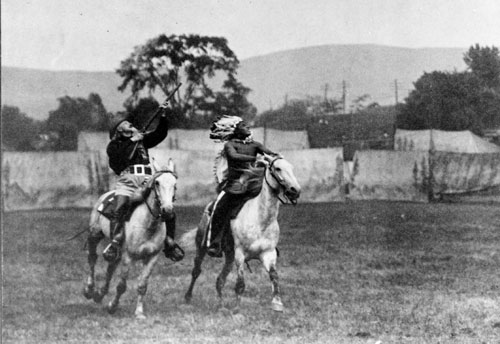

The show was as unique as the man. Far more than a circus or rodeo, his 1,000-member troupe featured exhibitions by talented riders and marksmen of the west. A typical show would include trick riding and races between cowboys as well as Native Americans. One of the big stars was the diminutive (4’11”) Annie Oakley who, shooting at a distance of 30 paces, could split playing cards edge-wise, hit dimes tossed in the air, or knock a cigarette from the lips of her husband.

The show also included western melodramas that mixed historical fact and fiction, like the re-enactment of Custer’s last stand, in which a regiment of cowboys dressed as soldiers were defeated by Indian riders. After the last man has fallen, Cody and his men would ride onto the scene too late to save Custer or his men. Next came the re-enactment of Cody’s shooting and scalping of the Cheyenne warrior Yellow Hand—a true occurrence—which was presented as his revenge for Custer. The final number was an attack by Native American horsemen on the cabin of a pioneer family. In this case, Buffalo Bill and his men arrived in time to drive off the Indians and save the white settlers.

Source: Library of Congress

The secret to the show’s remarkable success and long run—from 1883 to 1906—was Cody himself. He was more than a skilled marksman and horseman, he was the real thing—a true hero of the old west.

At the age of 11, he was working as a rider for a wagon train. Over the years, he found work as buffalo hunter, pony-express rider, trapper, prospector, and Army scout (which is how he earned the Medal of Honor).

In 1869, he came to the public’s attention when writer Ned Buntline made him the hero of one of his dime novels Buffalo Bill, The King of the Border Men. The book became a successful play. When Buntline wrote a second Cody play, Scout of the West, Cody agreed to play the lead, and for the next ten years, he appeared before the public as a theatrical version of himself.

During this time years, it appears Cody tried to copy Buntline’s success by writing a novel of his own. Prairie Prince, The Boy Outlaw; or, Trailed to His Doom, appeared in our October 16, 1875 issue.

The story opens with a young woman…

“A maiden upon whose sunny head but fifteen summer suns have shone.” She is wandering the prairie, stalked by a pair of hungry wolves. She is saved at the last minute by “a mere lad… tall in stature, well formed, with broad, square shoulders, small waist, and limbs of which an Apollo might well have been proud, while his every movement was graceful” etc.

When the young lady’s father, Major Racine, asks the identity of his daughter’s rescuer, an orderly says, “It is the Prairie Prince, sir.”

“No!” exclaims the Major. “Can this be that daring boy whose wonderful deeds have gone along the whole border, and have gained him the name of the Prairie Prince?” And Major Racine gazed with a strange interest into the boy’s face, while the soldiers crowded around and bent upon him looks of admiration and respect. Quietly, and with a proud smile upon his lip, the youth sat his horse, his clear, piercing eyes meeting the gaze of the military commander” etc.

The authorship is debatable. “Prairie Prince” might have been Cody’s own novel, or something Ned Buntline wrote under Cody’s name. If it was Cody’s work, he was smart not to make writing his future.

Source: Library of Congress

After a decade of playing someone else’s version of Buffalo Bill, Cody decided to present his own version of the character. On May 1, 1883, he premiered his Wild West show, appearing with a troupe of veteran cowhands and Indian riders from the Sioux tribe.

Up to that time, much of America’s entertainment was based on European styles and traditions. But Cody introduced the country to something wholly American. It was new, exciting, and home-grown.

A year after the Wild West opened, Cody received a letter from Mark Twain who praised the show–“It brought vividly back the breezy wild life of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, and stirred me like a war-song”–and encouraged Cody to take his “purely and distinctively American” show to Europe.

Three years later, Cody followed Twain’s advice. The Wild West troupe arrived in Great Britain in time for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Over the next four months, over 2.5 million Britons watched Cody’s spectacle and formed a general impression of Americans from this extraordinary showman.

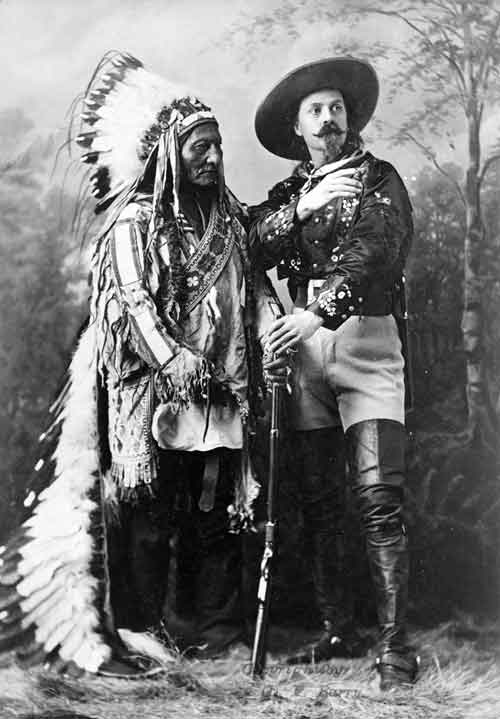

He wasn’t a bad representative of his countrymen. He was well-mannered, good-looking, and could skillfully handle a gun and a horse. And he was highly representative of Americans in his attitude toward the modern age. He regarded the past with a conflicted, sentimental perspective; he liked progress but hated the cost. He celebrated the white settlement of the west but regretted what it had destroyed.

His ambivalence can be seen in “Hunting Down the Buffalo,” which he wrote for the Post on July 15, 1899. “As late as 1869, General Sherman reported nine million buffaloes on the prairies, and this was a conservative estimate. Ten years later these vast herds were completely wiped out—a whole division of the animal kingdom stung to death by the bullets of wasteful professional hunters, who left millions of pounds of fine meat rotting in the sun.”

He assured Post readers that the slaughter was necessary: “It was a sharp, quick way of ridding the plains of a cumbrance that had to give place to a wiser use of these fine grazing lands. It was another instance of civilization getting what it wanted and never minding the cost.” It is a curious attitude for a man who earned his reputation and nickname for killing buffalo.

In the article, he drew a parallel between the fate of the buffalo and the Native American. “We could not make useful citizens of the Indian, and we could not run our brands on the buffalo, so now there are few Indians and no buffaloes.” Both, he believed, had fallen victim to the greed of white settlers.

His audience might not have shared this conclusion, but they were applauding it when they watched his show. His fair-minded attitude was part of the appeal of the Wild West. Like most superstars, his success came from an ability to see a little farther down the road than his audience.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

It was the Golden Jubilee

Of Queen Victoria’s long reign.

She wanted quite amused to be.

Buffalo Bill she did obtain,

His Wild West show from savage land.

The Prince of Wales had too much ale,

And picked a fight with a Sioux band.

The warriors whooped, the Prince did wail.

The Queen ordered all to chill some.

Buffalo Bill to the Prince called,

“Messing with Sioux is kind of dumb.”

“You’re just lucky that you are bald.”

Buffalo Bill amused the Queen,

The wildest stuff she’d ever seen.