North Country Girl: Chapter 21 — Youth in Revolt

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

The day after I saw The Who, I took the bus downtown to Musicland and bought my first record, The Who Sell Out; the album cover was a photo of Roger Daltrey bathing in Heinz Baked Beans. My mother shook her head at what she saw as a waste of $2.99. “You can listen to that music on the radio for free.” That was my cue, Youth in Revolt, to go back to Musicland and buy the new Rolling Stones album, Between the Buttons. I spent hours in my room listening to these two records, song after song, till the needle hit the sizzling rain drop song that indicated the end of that side, then flipping the record over, searching for clues to that other world like a radio astronomer listening for signs of life from distant stars.

I had no one who shared my new obsessions: rock and roll, drugs, sit-ins, protest marches, love-ins, be-ins, boys with long hair and romantic lacy shirts. Wendy’s mom’s two-year gig as dorm mother was up and they moved back to International Falls before the start of school. We promised to stay in touch, but phone calls would have been the dreaded Long Distance, so frowned on by my dad that my mom limited her calls to Aberdeen to two a year, one at Christmas and the other to let them know when we would be arriving for our summer visit. Wendy and I wrote, but letters didn’t capture the immediacy and high drama of the day-to-day junior high experience.

Despite my best friend’s departure, I wasn’t quite as lonely as a cloud when ninth grade started. I had a few girlfriends I sat with at lunch: Kathy O’Dell, Karen Ringwald, and Cindy Moreland, another newcomer to Duluth who had been taken in by our little group. But where were my fellow Youths in Revolt? Where were the readers of John Barth and John Updike, the fans of op art and experimental theatre, the anti-war protesters? Most importantly, where were kids who could get drugs? They were not at Woodland.

Kathy was a dreamy poet and painter, with long, blonde Michelle Phillips hair and perfect skin. She was waiting to be teleported to a garret in Paris, a black beret magically appearing on her head. Karen and I shared a reputation, guaranteed to impress no one, as the smartest girls in ninth grade, Karen slightly edging me out in math and routing me in Spanish. She was a 14-year-old cynic, dismissive of popular opinion, who regarded ninth grade boys as lower life forms. She vanished the next year, supposedly to some boarding school for super-smarties; this would have been the fodder of pregnancy rumors if it were any other girl besides Karen who disappeared.

Cindy Moreland was cute, perky, and as boy-crazy as I was, so the two of us eventually gravitated towards each other. We were far from soulmates; if I went to her house I had to listen to Gary Puckett’s “Young Girl” and “Girl You’ll be a Woman Soon” on repeat while we went through a box of Bugles and bottles of Coke and fretted over how to get boys to like us. At my house, I forced her to listen to The Who and The Rolling Stones, while we guzzled ginger ale (which was supposed to be for cocktails, not kids) and continued the discussion.

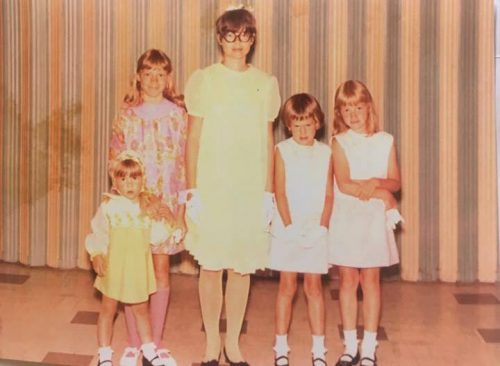

My mother, who generally ignored all kid goings-on, overheard us bemoaning our lack of success with boys. She was a former beauty queen, rising from Miss Aberdeen S.D. to Miss Upper Midwest, who had boyfriends coming out of her ears. Her advice was, along with always wearing cute clothes, to go up to a boy we like, say “Hi!” and start a conversation. This was the equivalent in my mind of suggesting I climb Everest.

Cindy was an optimist. Her taste ran strictly to jocks and she had a plan to reel one in: cheerleading. Football players and cheerleaders were as natural a combination as peanut butter and jelly. No actual gymnastic ability was required to be a Woodland Junior High cheerleader: all you had to do for the eight or so home games was yell and shake your pom poms. Since there is no justice in junior high, cute, peppy Cindy Moreland did not make the cheerleading squad; only the already gilded popular girls were chosen. Cindy was heartbroken and spent the rest of the year practicing splits and hand springs, determined to win a spot next fall on the East High School cheerleading squad.

The very idea of cheerleading made me want to puke, but I had enough Minnesota nice left that I did not make fun of Cindy’s goal. My own aspirations to become a war-protesting, civil-rights-marching, free-love-practicing pot smoker were much more ridiculous.

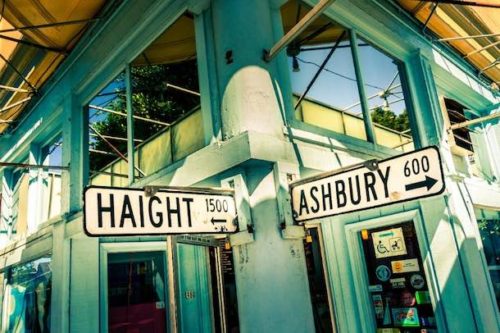

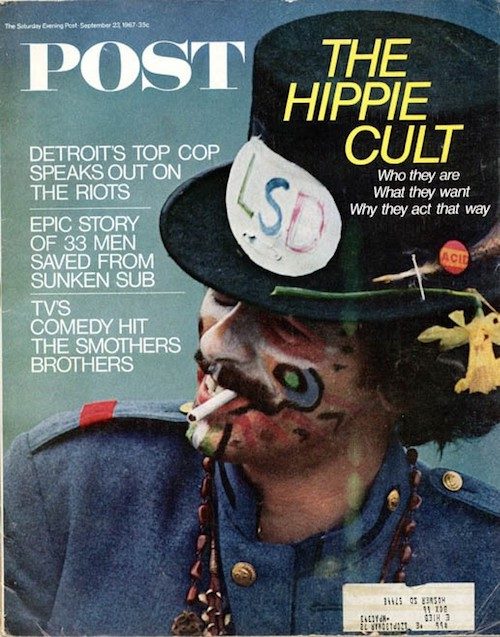

I devoured every bit of information on the counter culture that I could get my hands on. My sources were laughable. I pored over The Saturday Evening Post’s coverage of Haight-Ashbury and tried to figure out how to get there on the twenty-eight dollars I had in the Pioneer National bank.

Time magazine covered the anti-war protests, but with a maiden aunt’s tut tut of disapproval. But in the back pages of Time I found a tiny ad for a new magazine, Avant Garde, which promised to cover every subject needed by Youth in Revolt. I snipped out the ad, filled in my name and address and begged my mom for a five-dollar bill (special introductory price), and handed the envelope off to our mailman. A few months later, after I had forgotten all about it, I received a plain brown wrapper that enclosed a fat, glossy magazine. Avant Garde was all I desired and more: anti-war articles! Photos of stoned, unwashed hippies in squalid New York City apartments! Drawings from the Kama Sutra (what the hell were they doing?)! A whole article on the f-word, which I had never seen in print before! I had found my peephole into the 60s.

Unfortunately, the editors of Avant Garde must have believed that printing schedules were for squares, man; months would go by between issues. Even more unfortunately, my dad came across an issue I had thoughtlessly left on the living room couch. He had to look at only a few pages to know that his eldest daughter was in danger of being ruined by a magazine and thundered into my room, shaking the offending publication, and roaring that whoever wrote crap like this deserved to be horsewhipped. I was careful to hide all my issues after that.

Most unfortunate of all, Avant Garde kept taking my money, but stopped sending magazines. I sadly replaced it with the leftie Saturday Review, a magazine with all of the pretention of Avant Garde but with none of the panache.

***

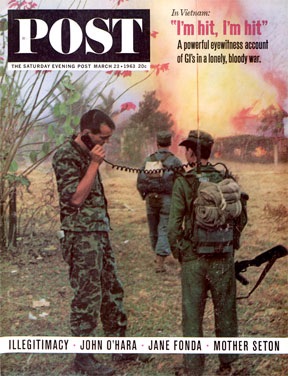

Stuck up in Duluth, I could only glimpse the revolution I knew was going on, a revolution I desperately wanted to be a part of but had no idea how to join. No one in Duluth marched against the Vietnam War.

The war was something on the TV news, or below the fold on the front page of the Duluth Tribune. I announced myself as anti-war at every opportunity, even though everyone I knew at that point, kids included, believed in the domino theory, that we needed to stop communism in Southeast Asia or we’d all be wearing Mao suits. My own parents didn’t give two sh*ts about the war; the biggest response I could get out of them when I spouted my revolutionary rhetoric was the eye roll. They did forbid me from letting slip any of my wacky new-found opinions in front of my commie-hating grandpa Haubner, lest I give the old man a heart attack.

Civil rights were also a non-starter in almost all-white Duluth. The only black person I had seen in Duluth in my ten years of living there was the elevator operator at Oreck’s department store. When she was five, my sister Lani had stared at the slight, well-dressed woman perched on her stool for a full minute before announcing “I don’t like your black face.” The elevator operator snapped back, “And I don’t like your little white face,” and my mother hustled us out of the elevator and we took the stairs up to Better Dresses.

I got my first chance to stick it to the man thanks to the Woodland Junior High dress code, which stipulated that girls’ skirts must be knee-length. It was the height of the miniskirt craze, and my mother, the slave to fashion, made sure that all my skirts for ninth grade were stylishly short.

My revolt would have sputtered out if it hadn’t been for my English teacher, Mr. Koch. No one else at Woodland cared about the length of the skirt worn by a boring, nerdy honor student with stumpy legs. The dress code ruled that when you got down on your knees, the hem of the skirt had to touch the floor. (No one acknowledged how demeaning it was to have to kneel down in public on the grubby linoleum school floor.)

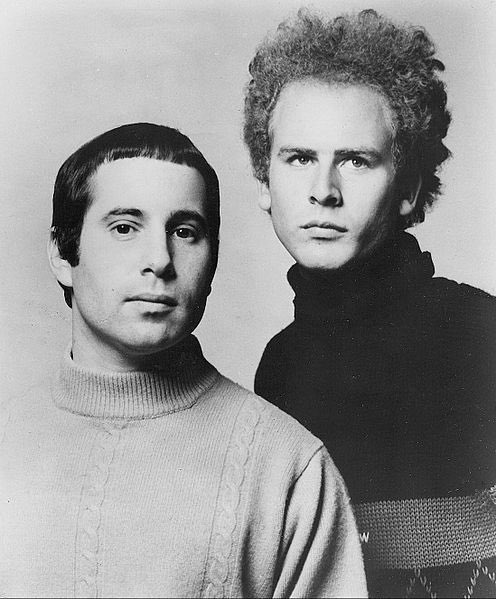

Mr. Koch, short and stubby, had turned his small black eyes on me from the beginning of the year. He wore a peevish look whenever I started in on my anti-war rhetoric. He grumbled when I chose the lyrics to Simon and Garfunkel’s “I am a Rock” for my poetry paper, threatened to make me redo it, and then awarded me a grudging B-.

Showing up in a shiny red pleather miniskirt was a serious transgression. Mr. Koch ordered me up to the front of the room, made me kneel, eyeballed the few inches between skirt and floor, inches occupied by my bony kneecaps, and sent me to the principal’s office. When the bored school secretary reached my mother and told her she needed to bring me a change of clothes, mom said the hell with that and that they better send me back to class or else. After all, she herself had plucked the skirt from the sales rack in Dayton’s Junior Miss department.

I had single-handedly put an end to the Woodland Dress Code. When I returned triumphant to Mr. Koch’s room, my classmates lined up to sign my pleather skirt in indelible black or blue Bic pen. My mother, horrified that I would ruin my clothes like that, threw it out.

My first successful act of rebellion put me directly in Mr. Koch’s sights. I pulled the trigger myself when during a class discussion I piped up to say that I couldn’t wait to try LSD, which sent Mr. Koch into a red-faced paroxysm. When he could speak again, it was to give me a series of mandatory extra assignments. Assignments that for some reason had to be completed in his apartment over several Saturdays. This situation was made even creepier by the flitting about of Mr. Koch’s all too cheerful wife, while I read Romeo and Juliet aloud at their kitchen table and Mr. Koch stared at me.

North Country Girl: Chapter 20 — The 60s Arrive in Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

In 1967, my eighth grade summer, the sixties finally trickled up to northern Minnesota. Up till then, we had existed in our own little insulated pocket of intact families, nosy neighbors, regular church-going, casual drunkenness, and a sincere belief in the virtue of conformity. Children were seen but not heard, teens were just big kids waiting to become adults, God was in his heaven, and all was right with the world.

Somewhere in the South people were marching for civil rights. Duluth had virtually no black people. We had a few grizzled Indians hanging around the liquor stores, waiting to buy booze for teen-agers in exchange for a few bucks or a can of beer. We had a handful of Jewish families, who were regarded suspiciously by my mother, although she had jumped at the chance to dump her two youngest kids in a half-day preschool at the Jewish Educational Center, where Lani, and later Heidi, learned to play the dreidel and build Sukkot tents.

Men were burning their draft cards in Berkeley and New York City; Walter Cronkite led off the news with stories of the war in Vietnam. But the college deferment was still in place, which meant that no boys who grew up in my neighborhood were at risk of being shot at by those awful Viet Cong.

Teen culture had started to seep in with the Beach Boys. But the California world of surfing and woodies seemed as exotic to us as an Indonesian dance troupe on Ed Sullivan. Our one and only radio station, WEBC (AM of course), played Top 40 music in an indiscriminate scramble: on a 15-minute drive to the store, we would hear “Ballad of the Green Berets,” “Monday, Monday,” and “Born Free.” When the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together” came out, WEBC beeped out the title line every time, in the interest of public morality.

But cracks were opening up. Time and The Saturday Evening Post, which arrived weekly at our house, increased their coverage of civil rights and anti-war protests, and I began to tilt left. The TV shows Hullabaloo and Shindig! moved away from Petula Clark and Bobby Darrin and towards the Doors (sex!) and Jefferson Airplane (drugs!).

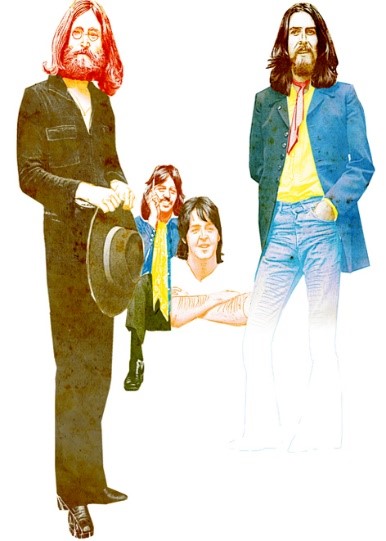

Drug culture took longer to reach us, too damn long as far as I was concerned. I had never succumbed to Beatlemania; the unwashed, sneering Rolling Stores were much more exciting. But it was mandatory that if you were between the ages of 13 and 21, you went gaga over the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I happily joined in, hoping that by listening to “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” I could get an aural contact high.

Somewhere, out in the real world, people were smoking marijuana and banana peels, ingesting morning glory seeds and LSD, expanding their consciousness in all kind of ways. But I was in a basement in International Falls, sitting around a tinny hi-fi system, with Sgt. Pepper on repeat and repeat, the record coming to a scratchy end and then flipped over, while the boy who lived there was dissolving Bayer aspirin in bottles of Coca-Cola, in an attempt to get himself and his pals, which included me but not my disapproving best friend, Wendy, high. We all claimed to feel something, although what I mostly felt was sick to my stomach.

I was huddled on that basement floor because that summer I was a long-term guest at Wendy’s grandma’s house. I had outgrown camp and the Northland Country Club pool. After the mandatory visit to Aberdeen, where I spent two weeks reading and sulking, my mother gratefully sent me north and out of her hair. International Falls was a small town, a lot like Aberdeen, but smellier, thanks to the paper mill. Wendy and I were regarded as sophisticated big city girls — “Wow, you live in Duluth!” —and welcomed everywhere. The day after the aspirin experiment, we were invited to a taffy pull at a neighbor’s, something I thought existed only in the pages of a Laura Ingalls Wilder book. My hands were buttered to the wrist, as if I were to be part of an adolescent orgy. The taffy was white and ropy and smelled of vanilla, and when finished was tooth-achingly sweet and tooth-shatteringly brittle. My father would have been horrified. I was annoyed at this wholesome party activity; I wanted to be back down in that basement, listening to records with boys and figuring out ways to get high.

I also participated in a bizarre experiment in reversing Down Syndrome. Wendy’s best friend before me had a baby sister with Down’s. I didn’t quite understand what was going on with this big-headed kid who couldn’t talk. The mom, searching for a cure, had fallen under the influence of a crack-pot theory that held that crawling was the basis of all subsequent learning. The mom spent hours manipulating her baby’s arms and legs in a swimming/crawling motion. When she got too tired she recruited anyone within shouting distance to take her place. I have no idea whether it helped or not. It was horribly creepy, moving the baby’s right arm and left leg for ten minutes, then switching to the left arm and right leg, while the kid made noises somewhere between a chortle and a howl. I hated going over to that house of sadness and madness.

The kid with the basement and the aspirin and the Sgt. Pepper’s album was International Fall’s leading Bad Boy. Wendy and I adored him. Several weeks into my visit, all of us 13-year-old aspiring juvenile delinquents were hanging out on a street corner, trying to be much cooler than we actually were. Bad Boy was smoking a cigarette (oooh!) and started lighting matches and tossing them into a red and blue mailbox. Of course, we found this, as everything Bad Boy did, hysterical. At about the twentieth match, smoke began seeping through the mailbox slot. All of us stood gazing horrified as the wisp became a serious plume, a “Yeah something is really burning” smoke signal. One of Bad Boy’s friends helpfully noted that we had probably committed a federal crime, setting the U.S. mail on fire. As the smoke darkened and streamed out of the mailbox, we fled in all four directions. Wendy and I bamboozled her poor grandma with some story about why we had to be back in Duluth immediately, and pooled our money for bus tickets, hoping to stay one step ahead of the law.

***

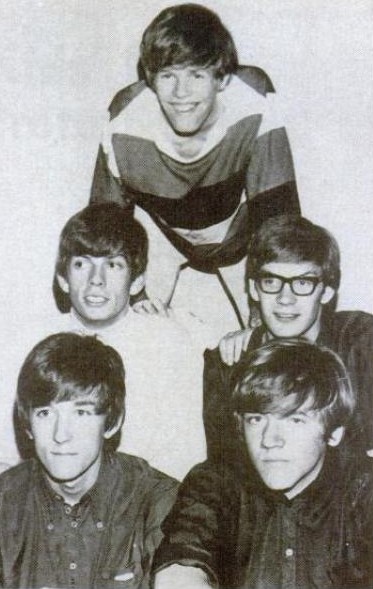

I got back to Duluth to find the entire teen universe abuzz. The Duluth auditorium, which had opened in 1966 and been home to hockey games, Ice Capades, and the Ringling Brothers Circus, was to have its first rock concert: Herman’s Hermits.

Wendy and I were speechless with joy. While Herman, aka Peter Noone, the lead singer, was almost a little too preciously adorable for my tastes (always a smile, never a sneer), he was undeniably cute. And I, like everyone under 25 in the country, had fallen under the perky, head-bobbing spell of “I’m Henry the Eighth, I Am,” which was played by the radio station at least once every hour, causing pre-teen girls to squeal, hop on one foot, and shout out “Second verse, same as the first!”

For weeks before the concert, I was lost in a whirl of daydreams where Peter Noone looked out in the audience, saw my adoring face, and fell madly in love. He would send someone out to escort me backstage, take me in his arms, kiss me, gently remove my clothes…and then stuff would happen that I was still having a difficult time imagining. I would get to that crucial point, sigh, and rewind my daydream back to the beginning.

There was only one problem. I wore glasses, thick, hideous glasses which could kill the sex drive of any boy at ten paces. I could go to the concert without wearing my brown cat’s eye with sparkles (an improvement over the baby blue ones I had worn for years) but then I wouldn’t be able to see a thing onstage. How could I catch Peter Noone’s eye if he were just a fuzzy object? I wouldn’t even be able to tell him from the lesser, unnamed Hermits.

Shindig!, the TV music show, saved me. It was on during a school night, so Wendy and I had to watch it at our own homes, one ear glued to the phone, discussing which bands and boys we liked. Shindig! had a troupe of cute girl dancers (now there was a career!). One of these dancers wore, along with her mini skirts, Mondrian-inspired dresses, and go-go boots, a pair of perfectly round tortoise shell glasses. Thanks to some mysterious seismic movement or an alignment of the stars, a pair of those exact glasses showed up at my eye doctor’s, where before my choice had been between the baby blue or shit brown cat’s eyes with sparkles. My mother, the slave to fashion, was always delighted when I paid attention to what I wore and how I looked — which was still, with my badly cut mousy blonde hair, not good. But at least with my outrageously stylish new glasses, I commanded some attention from boys, most of it a startled reaction of “Weird.”

With my Shindig glasses and my own Mondrian color block mini dress, I was ready for Peter Noone to sweep me off my feet. I don’t remember what Wendy was wearing. It didn’t matter, she was only there to report back to all of Woodland Junior High that I was not in ninth grade because I had eloped with Herman.

My dad, who had been known to whistle “Henry the Eighth” himself occasionally, scored us seats a few rows from the stage. We had to sit through an opening act before Herman’s Hermits came on. That band was The Who. I had heard “I Can See for Miles” on WEBC a few times the winter before, enjoyed it, but relegated The Who to the category of British Bands I Kinda Liked: The Kinks, The Animals, The Zombies.

Seeing The Who live rocked my little Duluthian world. There I was, nicely dressed, waiting to see that sweet young man who politely told Mrs. Brown she had a lovely daughter. I got Roger Daltrey’s unhinged vocals (ooh, he was really cute!), Keith Moon’s spastic flailing over his drums, and Pete Townsend smashing his guitar on the stage floor over and over (and John Entwhistle noodling about in the background). The Who killed off any residual Minnesota nice girl in me and I was pitched head first into full-fledged Youth in Revolt. At the end of “I Can See for Miles” Townsend stomped offstage with the splintered neck of his guitar in hand while everyone around me politely applauded while muttering “Were they on drugs? What was that all about?” I knew what it was about, it was about smashing the old to make way for something completely new, whether the world or Duluth or Woodland Junior High was ready for it or not.

The crowd stood and roared when Herman’s Hermits took the stage; I was still in a daze; sorry Peter Noone, you are no longer my type.

North Country Girl: Chapter 16 — Junior High School: Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

The back to school letter from Congdon did not bring good news. The enrichment program at Endion was supposed to be for two years: fifth and sixth grade. But yet another revolution in educational theory had hit Congdon, and the school pulled the five of us smarty pants out of the program, so we could enjoy all the benefits of the new system.

A modern extension had been wadded on to the old brick school building for Congdon fifth and sixth graders; we were to be the guinea pigs for a new “modular” elementary education. Someone had finally realized that teachers who graduated from college before World War II, and whose educational ideal was a pin-drop quiet classroom with seasonally decorated bulletin boards might not be capable of instructing students in higher math skills or science that wasn’t a slowly dying terrarium. Miss Ritchie, I’m afraid they were looking at you.

Instead of a single classroom teacher, we now had four, each one with a specialty: English, Social Science, Math, and Science. The new teachers were all under forty and to our shock, two of them were male—I didn’t think men were allowed to be elementary school teachers. The teachers each had their own room with new lightweight desks, so we had four different desks to keep our stuff in. Since each class of students moved from room to room during the school day, none of us except the most anal of twelve-year-old girls ever had the right books, pencils, or writing paper for the class we were in. The first ten minutes of every class was spent repositioning our desks in small groups or a big circle or in rows, or an original configuration, if the teacher could think of one, with chair legs screeching against the linoleum, and “ouches” and “ows” as we banged into each other, jockeying for position next to the most popular kids. The next ten minutes was spent scrounging for supplies that had been left in the previous classroom. Under this new regime, art and music fell by the wayside. I guess the amount of time we had spent in previous years creating shoebox dioramas and learning to sing “White Coral Bells” as a round was considered adequate.

The male teachers took over gym, and competitive games ruled. Out went square dancing, in came high velocity dodgeball. I was not only always chosen last, but also managed to get hit as soon as possible by placing myself directly in front of the first ball languidly tossed over by a girl on the other side. In this way I avoided being concussed by one of the boys’ vicious fastballs, and I got to spend gym period sitting dreamily on the sidelines, missing my wonderful enrichment class and imagining I was watching the Olympics in ancient Greece before strolling down to the Acropolis. During one particularly brutal game, when it got down to two players on each side, husky Mr. Levine, nominally our math teacher, pointed at Billy Shaw and called “Out!” to which Billy Shaw replied “F**k you, Mr. Levine.” Mr. Levine charged Billy like a freight train and proceeded to beat the shit out of him all around the gym. The rest of us huddled together, like wildebeests watching one of our own being devoured by a lion, and tried to get as far away as possible from the pummeling. This incident did not result in a dodgeball ban, or even in a reduction of the fierceness of the competition, which remained at major head injury level; there was just less audible cursing from the boys, and I continued to be able to avoid getting any exercise in gym.

For the first time in our collective student memory, there was a new girl in our class. Becky Sweet, a blonde so slight and pale she looked in danger of toppling over, was a pro at being the new kid: her father was a minister of some obscure Nordic-based Protestant denomination and was assigned to a different Minnesota town every few years. Becky had vast experience in recognizing which girl needed a friend the most and lit on me as her new best friend. I had never had another kid choose me for anything before, and fell into best friendship without a thought.

Becky was obsessed with sex and George Harrison and had the oddest family life I had every seen. She would not come to my home, but insisted that I sleep over at her house every Friday. I never once met her father. His work took him all around upper Minnesota and Wisconsin, driving to small farm towns to stand in for ministers who had dropped dead or shot their wives or been caught tampering with the livestock. Or he was at church, counseling parishioners, or rarely, in his study, NOT TO BE DISTURBED.

Becky’s mother was also a ghostly presence. I would catch a glimpse of her when I walked into their house, wafting from room to room before vanishing into her bedroom. Becky and I were left with her older sister, who supervised the making of huge bowls of popcorn, dinner for the three of us, washed down with Hawaiian Punch, about as transgressive a dinner as I could imagine. Then a car pulled up, a boy shouting and blasting the horn, and big sis would take off for the night. Becky and I settled down on her couch to watch the Friday Night Fright Fest, old black and white sci-fi movies where radiation would create giant women, tiny men, and plants that could walk and eat people. When the Duluth broadcasting day ended at midnight, Becky and I climbed into her bed, back to back. I fell asleep listening to her explicit fantasies about having sex with George Harrison, the important details of the act having been supplied to her by her sister. Had I met Becky the year before, I wouldn’t have cared about missing the “Becoming a Woman” educational film and I would have been voted Most Knowledgeable About Sex at Camp Wanakiwin. Becky’s obsession was almost innocent: she didn’t try to touch me and I don’t think she touched herself. Unlike the other Beatle-crazed girls I knew, Becky didn’t press me to pick a favorite Beatle. I was the audience for her stories about George Harrison and his undying lust for her pre-pubescent body To me it was far from erotic; it was just another piece of Becky’s Bizarro World, like the missing parents, the wooden crosses on every wall, and the fridge that held nothing except can after can of Hawaiian Punch.

These Friday nights were a dark, musky secret at the heart of our friendship. My mom was too busy with an infant and a missing six-year-old to ask about my sleepovers at Becky’s, so she never knew about the popcorn dinners, staying up until midnight, or the lack of adult supervision. Since Mrs. Sweet never seemed to leave the house, she was far out of my mother’s social orbit; mom felt no compunction to invite Becky to sleep over at our house, as she would for a daughter of a matron of long Duluth standing. Becky never showed the least desire to come to my house; a real dinner might have been a serious blow to her digestive system.

Then in the spring, Becky was gone, her father sent off to another parish. Because I had been away from Congdon at the enrichment program for half the year during fifth grade and held in isolation by Becky Sweet for most of sixth, I was now completely friendless. I read, watched TV, held my baby sister, and kept an eye out in case Lani reappeared.

***

The street where I lived, Lakeview Avenue, was on the very border of zoning for two Junior High Schools, Ordean and Woodland, so I could opt to go to either one. I was the only one in the Congdon sixth grade to occupy this geographic odd spot; all of the other kids lived in the Ordean zone and were headed there.

I took stock of my friendless state and decided that I needed a fresh start. I was the four-eyed bookworm, the eternal teacher’s pet, the kid you did not want on your dodgeball, volleyball, or softball team. But if I went to Woodland Junior High, I could re-invent myself! I could be a woman (girl) of mystery. Girls would want to whisper to me about other girls and pass notes about which boys they liked, and boys would want to walk me home, carry my books, and hold my hand. I could be cool.

My fantasies were not unlike Becky’s. Somehow she would meet George Harrison and he would be smitten with love for her. Somehow I would enter Woodland Junior High and be popular. Before our pre-school shopping trip to Minneapolis, I pored over Seventeen magazine, noted that grape and rust were the in colors for fall. From the “Back to School” racks of clothing I carefully selected skirts and dresses in those hideous shades, all at a slightly above knee length, as I had been instructed by Seventeen. My mother, the shopaholic and former beauty queen, was delighted that I was turning into a real girl.

I thought I was ready to conquer Woodland Junior High, an uninspired white brick two-story building, bland as boiled rice on the outside; inside held a disturbing whiff of chlorine from the pool and all the miseries of being a pre-teen girl. The boys contributed their own smell: sweat, Clearasil, Right Guard, and the Jade East cologne worn by sophisticated ninth graders. This smell permeated the halls we streamed through, every hour, year after year, as we traveled from one classroom to the next.

I had been overconfident in my ability to transform myself; the scratchy new sweater the color of Welch’s Grape Jelly and the coordinated plaid skirt were not enough. Clothes do not make the seventh grade girl, a lesson I seemed incapable of learning.

The first morning of Junior High was filled with the excitement and confusion of a hundred new students trying to find their different classrooms, prompted by a confusing buzz of the school bell every fifty minutes, overseen by bored teachers trying to determine if you were in the right class. When the noon bell sounded, I followed the seventh grade shift of lunchers into the gigantic cafeteria.

I waited in the endless school lunch line and wished I had brought a packed lunch, looking out at the tables already crowded with kids pulling sandwiches out of brown paper bags. When I finally got my tray I stood in the center of the cacophony in my new duds, grinning like Alfred E. Newman, and waiting for someone to wave me to their table. My stomach and my heart squeezed together as I realized that my plan was not going to work. All the girls already had their cliques from elementary school; new comers need not apply. And I am sure that not a single seventh grade boy noticed that I was dressed out the pages of a Seventeen magazine.

I tossed the contents of my tray into the garbage and spent the rest of the lunch hour weeping silently in a bathroom stall.

North Country Girl: Chapter 12 — Country Club Days

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My sister Lani and I arrived home to the big news that my dad had switched country clubs. For years he had played golf at Ridgeway Country Club, a mysterious place with a ramshackle clubhouse that I had only glimpsed from the outside when my mom dropped off my dad and his club. Ridgeway members golfed, drank, smoked, and played cards; there were no Ladies’ Days or children’s programs.

Now my dad was a member at Northland Country Club, about as waspy a place as could be in Duluth. No Jews of course, and the inclination would probably have been to exclude Catholics as well, except that Duluth had a deep base of Norwegians who were local business and government bigwigs, as well as supporters of the Church.

Northland’s clubhouse was a gleaming white pseudo-mansion that would not have looked out of place on an antebellum plantation, complete with porte-cochere in the front and a two-story columned patio on the side. There was even a guardhouse at the turn off of Superior Street where you had to stop to have your name checked against the membership roll before proceeding up the long driveway. At the top, nestled beside the clubhouse, was a (semi-) heated pool. After being frog marched into the frigid water of Hanging Horn Lake for swimming lessons at camp, Lani and I took the Northland pool as if it were the Caribbean. The only other pool I had been to in Duluth was the indoor one at Woodland Junior High, where I was forced to take swimming lessons year after year, never passing into a higher category than Minnow. It was impossible to learn to swim in that over-chlorinated, dimly lit Woodland pool. It had a ledge all around it made of concrete mixed with pumice and bits of sandpaper that would take the skin off your legs and arms, and was surrounded by tiles so slippery that anything faster than a trudge resulted in immediate expulsion from the swimming class. And since the pool was inside the school, it was thought not necessary to heat it.

Thrilled with the chance to swim in water that was over 70 degrees, Lani and I spent the rest of the summer begging, “Can we go to the pool? Can we go to the pool?” from the time we woke up. When we got to Northland, Lani and I (always having to wait the mandatory thirty minutes if we were there after lunch) gleefully plunged into the pool, tossing beach balls, playing water tag, having breath holding contests, going off the diving board (only allowed after you proved you could swim the length of the pool) and staying in the water all afternoon, emerging at five when the pool closed, blue-lipped and prune-fingered.

Oddly enough, none of my classmates’ families belonged to Northland and most of the kids who were regulars at the pool were younger than I. Lani’s best friend Julie Luster often joined us while her mother golfed or drank at the club bar on Ladies’ Day. Children were not allowed to be at the pool by themselves. Your mother or another member had to sign you in and stay there, so there was always a circle of trapped moms trying to get a hint of a tan from the weak Minnesota sun while regularly being drenched by kids cannon-balling or getting in a forbidden game of chicken while the lifeguard’s back was turned.

Northland’s pool, snack bar, hamburgers and fries served on the patio — along with family Fourth of July parties with sack races, hot dogs, and fireworks — was heaven enough for me. But my parents wanted me to enjoy all the benefits of Northland membership, which included golf and tennis lessons for kids. I had learned to hate tennis at camp, but golf brought me to new levels of wishing I never had to do anything besides sit on the sofa and read. Mini-golf was fun; colored balls, little windmills, a chance to hit your sister with the putter. Golf lessons were ten weeks spent just on my stance, swinging the club at an imaginary ball, then having my body manipulated by a creepy assistant golf pro so I could swing at nothing again. When I was finally given a real golf ball, I managed to sideswipe it, knocking the ball off the tee onto the grass. I was ordered back to stance school, at which point I put my club and feet down and refused to go to golf lessons ever again.

***

In fifth grade I was one of the white mice in another of Duluth’s experiments in education. As a result of all that testing the year before, it was determined that five Congdon fifth graders — me and four boys — deserved “enrichment education.” We would spend our mornings in a special class at Endion Elementary and afternoons at Congdon. I have no idea how my Congdon teacher, the huge Miss Johnson, felt about this. During all my previous elementary school years, there was never any schedule for the day. After we said the Pledge of Allegiance, we might have math or social studies or reading, whatever the teacher felt like teaching. We would go weeks without taking out our music books and then sing for an hour every day for three weeks. But because the five of us would receive “enriched” instruction in English and social studies, Miss Johnson was forced to structure her day to cover those subjects in the morning. In the afternoons, when we were back at Congdon, Miss Johnson would teach math, a smidgen of science (none of those spinster teachers cared about science at all), art, music, and whatever else needed to be taught.

Since there were five of us, the five mothers each took a day of the week to pick all of us up (two kids in the front, three in the back, and please please please don’t let me be squeezed between two boys) in the morning, then shuttle us back to Congdon in time for lunch. It was kind of a requirement for our enriched education, as no other form of transport was offered. My mother bitched — as probably the other four mothers did — every time her day to drive came around.

I loved the Endion Elementary enrichment classes, and I adored our teacher. Miss Steinbeck, a classicist, took us through ancient history, from Egypt to Rome. We wrote stories set in those eras, acted out Greek myths, built a tiny Acropolis, studied sculpture and urns and pyramids. It was a geek’s paradise.

It was also the perfect way to make a socially awkward girl like me even more so. Just being out of my regular Congdon class half the day made me an oddball. When I had nothing more exciting to report to my classmates about the mysterious doings of our morning enrichment class than “We looked at hieroglyphics,” I went back to being ignored and then even further alienated from fifth grade girls’ society.

The educational powers that be weren’t done yet. Several students were also pulled out of Miss Johnson’s room one afternoon a week for a special creative writing class, including Nancy Erman, the one friend I had left. I was consumed with jealousy, as it was universally accepted that I was the best writer in fifth grade. Being told that the only reason I didn’t get to go to creative writing was because I was already pulled out of class half the day did not make me feel any better, and I am afraid I was a snotty little bitch to Nancy for quite a while.

Because I was not enough of a weirdo, there came the afternoon when Miss Johnson escorted the girls out of the classroom and down to the gym. Everyone, she announced, “except Gay. Your mother didn’t sign the permission slip.” Every eye, boy and girl, turned towards me as I tried to will myself invisible. Two hours later, the girls returned, giggling and pinching each other. I was too humiliated to ask what I had missed.

I finally got Nancy to tell me. It was a movie about menstruation, sponsored by Modess sanitary pads, starring a caterpillar who turns into a butterfly. Obviously all the other girls would now metamorphose into butterflies while I would remain a lowly caterpillar. I held back my tears till I got home, where my hysterics were poo-pooed by my mother, the cause of my shame. She had received the letter from the school about the movie, decided I was too young to learn about these things (I had kept the info shared by the Applebaum cousins to myself), and tossed the permission slip into the garbage. “I didn’t know you’d be the only one,” she shrugged.

My sex education was complete enough to be equally thrilled and embarrassed when my mother announced that she was pregnant. To me, my mother always seemed much younger than other moms; Nancy Erman had a brother and sister who were in college and her grey-haired mother seemed as old as my grandmothers. The year before my parents had been photographed for the Duluth Tribune learning to do that new dance craze, the Twist. The world had not yet been turned over to teen-agers; thirty-year-olds could still be cool.

Around the time my mother’s pregnancy began to show, other women started asking with suspicious frequency how old she was. Mom, who had always been paranoid about revealing her age, thought they were hinting about getting pregnant at her advanced age, and refused to answer. I heard her constantly griping, “Old biddies, why do they want to know how old I am?” Someone clued her in to the fact she was being vetted for the Junior League, a club that believed itself to be the pinnacle of high society among Duluth women. My mom had been nominated for Junior League but there was a hitch: you had to be under 35 to join the Junior League. But no one came out and said that why she was asking about my mom’s age, I guess in case my mom got blackballed, so she wouldn’t have hurt feelings.

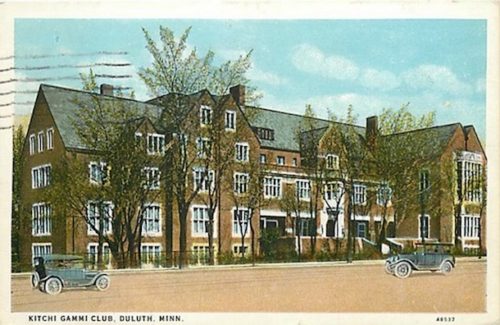

Duluthians of that time loved joining things: churches (everyone belong to some church, Catholic, Lutheran, Congregationalist, even the mysterious Jewish temple), country clubs, Elks, Moose, Rotary, Lion’s Club, the weird Knights of Columbus and the even odder Masons. My mother was a member of the Women’s Dental Auxiliary and drove around the county distributing toothbrushes and toothpaste to rural schools. My Carlton grandmother was a member of the hoity-toity Kitchi Gammi club, where I was once invited to lunch with her in its cavernous, echoing dining room.

I must have done something wrong — pushed my soup spoon the wrong way or stained the snowy table cloth — as the invitation was not repeated. Grandma Marie was also a member of the Women’s Club, the mother organization to the Junior League, a bunch of do-gooders who were best known for the Duluth Women’s Club Parade of Homes, a chance to poke around in other people’s over-decorated houses for charity.

Why my grandmother Marie couldn’t have just shepherded my mom into Junior League is a mystery. Maybe she was too much of a snob and thought a house painter’s daughter from Aberdeen, South Dakota, even if she was her daughter-in-law, wasn’t good enough to raise money for the Duluth Symphony or the Leif Erickson Park rose gardens.

Alas, my mother never became a Junior Leaguer. Even in an organization composed entirely of women, the husbands had to be considered. My father missed the mandatory Saturday breakfast meeting where my mother was to be interviewed for inclusion in the club; he was too hung over. The Junior League gave him a second chance, he missed that one too.