News of the Week: Star Trek 4, Retro Nintendo, and a Little Penuche (What the Heck Is Penuche?)

Beyond Star Trek Beyond

The third of J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek movies, Star Trek Beyond, hasn’t even hit theaters yet — it opens later today — but we’re already getting news about the fourth one. And this movie will be tied into events from the first.

In a press release this week, Abrams says that the fourth film will feature Chris Hemsworth as Kirk’s father. Hemsworth played the role in the first film in the series but only for what amounted to a cameo, as he quickly died. So it looks like this will be another time-travel adventure. I wonder if they’ll once again mess with the Trek timeline, maybe somehow putting it back to the way it was after changing it in the first film.

Abrams also says that the role of Chekov will not be recast in the fourth movie, following the death of Anton Yelchin.

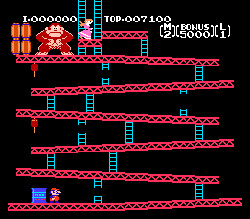

Nintendo Goes Retro

I don’t play video games anymore, but if I did, I might buy something like this. It’s not the first game system of its type, but it comes with a lot of games and it’s pretty inexpensive. It’s the NES Classic Edition. It’s a mini-console that comes with 30 games already built in (no need for cartridges), including The Legend of Zelda, Donkey Kong, Galaga (which I was addicted to as a teen), Mario Bros., and Pac-Man. It will sell for $59.99 and will come out in November, just in time for Christmas.

Los Angeles: 1940s vs. 2016

The most recent video game I’ve played is L.A. Noire, a fun game that makes you a detective in 1940’s Los Angeles. It looks fantastic, with beautifully rendered cars and buildings. It’s the type of game where you don’t even have to play it. It’s a joy just to get into one of the cars and drive around.

I thought of the game after watching this video by Keven McAlester. It’s a 2016 retracing of a car trip someone made in the Bunker Hill section of Los Angeles in 1940. You get to watch the two videos side by side to see the changes (and there are many) to the area in the past 70 years. Bunker Hill was used in a lot of movies back then, especially film noir, but the city started a large redevelopment project in the area in 1959, which ended only a few years ago.

Confessions of a Republican, Part II

Remember back in March when I posted the video of the famous 1964 LBJ ad “Confessions of a Republican”? A lot of people thought that if you inserted the name “Trump” for “Goldwater,” it still works today. Well, it looks like Hillary Clinton’s campaign thought the same thing, as this week they released an update of the ad … with the same actor, William Bogert!

Oddly, I didn’t see this ad played at this week’s GOP convention in Cleveland.

RIP Garry Marshall and Norman Abbott

Garry Marshall passed away Tuesday at the age of 81. Before directing such movies as Pretty Woman, The Flamingo Kid, and The Princess Diaries, he was a writer/director/producer on a ton of classic shows, including The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Odd Couple, Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley, Mork & Mindy, The Lucy Show, and Make Room For Daddy. He acted in over 80 TV shows and movies, too. His sister is director and actress Penny Marshall.

The Washington Post has a list of careers that Marshall helped launch.

Norman Abbott was the nephew of comic Bud Abbott. After starting out as an actor, appearing in such films as the Abbott and Costello comedy Who Done It? and Walking My Baby Back Home, he became a top sitcom director. He directed many episodes of Leave It to Beaver, including the classic episode where Beaver falls into a giant bowl of soup, as well as The Jack Benny Program, Get Smart, McHale’s Navy, The Brady Bunch, Welcome Back, Kotter, Alice, The Munsters, and Sanford and Son. He was also a stage manager on I Love Lucy and the man behind the Broadway hit Sugar Babies. He served in World War II in the original Navy SEALs unit.

Abbott passed away at the age of 93 in Valencia, California.

How Did They Do That?

Last week I showed you a video of one of the finalists for the 2016 Illusion of the Year Award, and I promised that this week I’d tell you how it’s done.

The answer: It’s real magic!

Well, no. It’s actually simpler than that. There really is no “trick”; the shapes used look different depending on what angle you’re viewing them from. You can even see that if you pause the video when the shapes are turned around in front of the mirror.

Here’s a video that explains how it’s done:

Today Is National Penuche Day

Penuche is one of those foods that I’ve never heard of before but have eaten plenty of. Does that make sense? I mean I’ve eaten it but never knew what it was really called. I always just called it fudge, But penuche is lighter in color and made with brown sugar.

Here’s a recipe for penuche from Fearless Fresh. In fact, it’s two recipes. A new recipe was created for the site because the original didn’t set right. Both are included if you want to experiment and see which one works.

Or if you don’t want to bother making penuche, you could just buy some.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

Pioneer Day in Utah (July 24)

This official holiday celebrates the arrival of Brigham Young and his group of Mormon pioneers into Salt Lake Valley.

Discovery of Machu Picchu (July 24, 1911)

Archaeologists believe the mountain sanctuary was built for Incan emperor Pachacuti.

Mick Jagger born (July 25, 1943)

He may have been born during World War II, but he’s about to become a father again.

Sinking of the Andrea Doria (July 25, 1956)

The Italian passenger liner collided with the Stockholm near Nantucket, Massachusetts; 46 passengers and crew died.

United States Post Office established (July 26, 1775)

What became the United States Postal Service in 1970 has gone through financial problems in recent years, and the idea of stopping Saturday delivery is brought up every now and then.

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis born (July 28, 1929)

After the deaths of husbands John F. Kennedy and Aristotle Onassis, she became a respected editor at Viking Press and Doubleday.

News of the Week: Led Zep & Lawsuits, Books & Beer, Podcasts & Picnics

Led Zeppelin 1, Spirit 0

A jury in Los Angeles has decided that Led Zeppelin didn’t rip off another song when they wrote “Stairway to Heaven.”

It took them five hours to decide that Robert Plant and Jimmy Page didn’t copy parts of the song “Taurus” by the band Spirit when creating the opening melody to “Stairway to Heaven.” The plaintiffs tried to show that Plant and Page had seen Spirit in concert in the ’60s and even owned the band’s album, while the defendants tried to show that the chord progression used in the song’s intro was common. Interestingly, Plant admitted that Led Zeppelin did use parts of another Spirit song in a medley early in their career.

Here’s that passage from “Stairway to Heaven” followed by “Taurus.” You make the call:

Barnes & Noble, Beer & Wine

These days, a bookstore can’t survive by just selling books.

Barnes & Noble is trying something new later this year: They’re opening up four “concept” locations that will feature beer and wine in redesigned cafes, along with table service and a new menu. The first store will open in Eastchester, New York, in October.

This is actually a great idea. I’ve been to combo restaurants/bookstores before (like Trident on Newbury Street in Boston), but I hope they’re massively redesigned cafes. The Barnes & Noble location I frequent has the tiniest tables inside a really crowded cafe. It’s almost as if they don’t want you to stay there and drink their drinks and eat their food (Borders was a lot better). But I’m sure they won’t mind if you want to meet people for dinner and buy several glasses of wine.

A B&N exec described their forthcoming comestible fare as “shareable, American food.” I’m not exactly sure what that is. Pizza? Apple pie? Cookies shaped like Abraham Lincoln?

RIP Scotty Moore

Scotty Moore was Elvis Presley’s guitarist. In 1954, he was in a band called Doug Poindexter and the Starlite Wranglers — they had the best band names in the ’50s — when he was asked by producer Sam Phillips to audition a young singer. Moore told Phillips that Presley wasn’t great but he might be okay with some work.

Here they are performing “Hound Dog” in 1956:

It’s hard to overstate how influential and important Moore was. He was one of the people who invented rock ’n’ roll and rockabilly, and many guitarists will tell you how much they were influenced by him.

Moore passed away on Tuesday at the age of 84 in Nashville. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000.

In happier RIP news, writer Cormac McCarthy — who won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for The Road — didn’t die this week, no matter what USA Today said.

WWI Tunnels Found

Here’s a cool find deep in the forests of Northern France: secret tunnels from World War I!

An explorer recently found the tunnels, which were created by the American Expeditionary Force sent to the area to help out Britain and France. Inside the tunnels, the explorer found 250 ornate insignias and faces carved into the walls and pillars of the tunnels by the soldiers.

You think that everything that could be discovered about World War I and World War II has already been discovered, and then something like this happens.

Bob Barker Wants CBS to Be Spayed or Neutered

I haven’t seen any of CBS’s sci-fi drama Zoo, though I feel like I have. I’m pretty sure they run the promos for it on a continuous loop in a little box in the corner of the TV screen, 24/7. I’ve seen so many commercials for it that I feel like I already know what’s going on and don’t really have to watch it every week.

Bob Barker isn’t a fan of the show. The former Price Is Right host wants CBS to use special effects on the show instead of actual animals. Barker wrote a letter to the network outlining why he and PETA think that CGI should be used on the show instead of subjecting animals to “abusive training methods” and keeping them “locked inside tiny cages.” It should be noted that there haven’t been any reports of animals being abused for Zoo and that Barker is talking more about the general mistreatment of animals in Hollywood over the years.

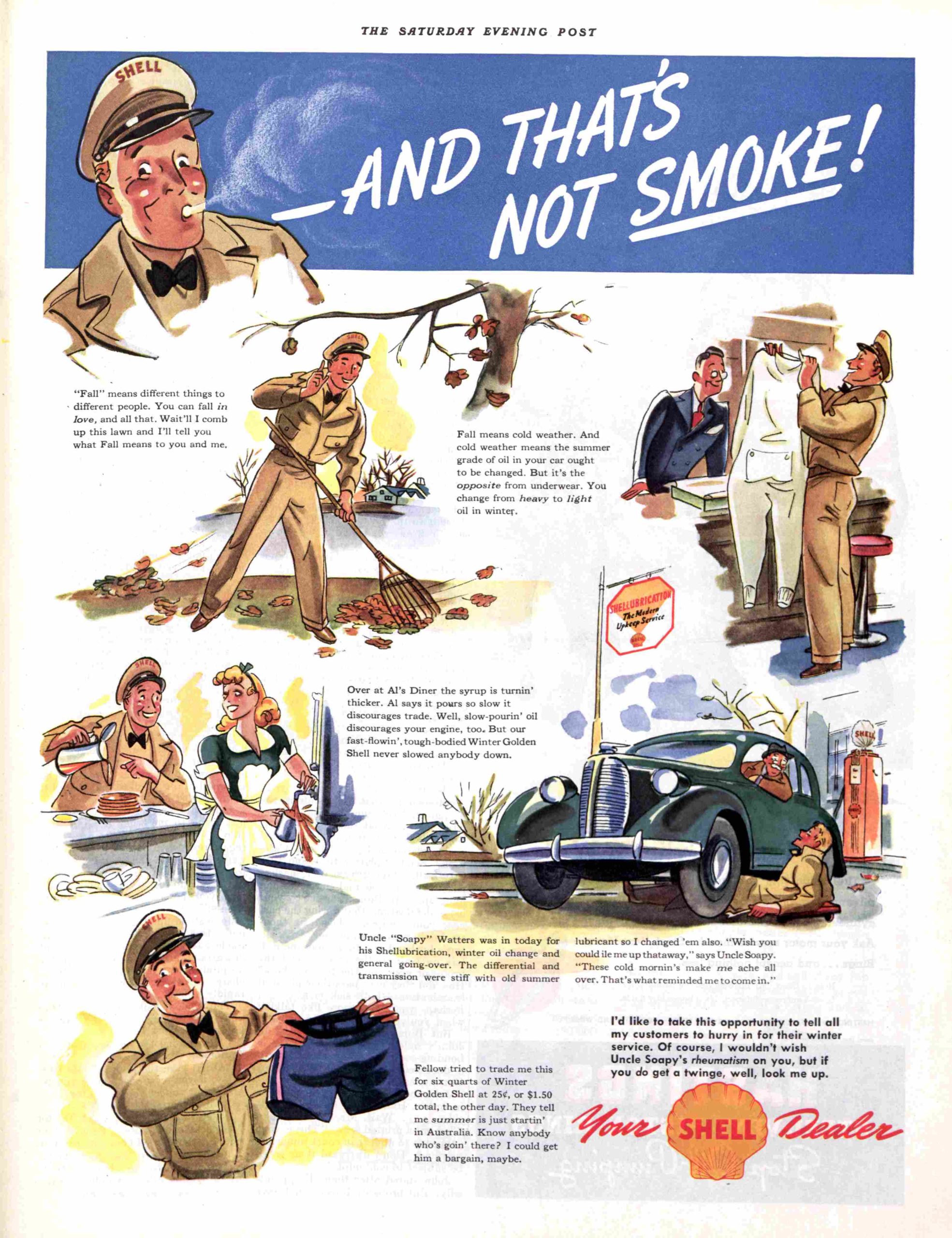

Barker actually talked about what he thought of zoos in his Saturday Evening Post chat with Jeanne Wolf.

Podcasts You Should Listen To

I don’t listen to enough podcasts. There are just so many, and so many that are good, that I get overwhelmed and don’t want to investigate to find out which ones are worth listening to regularly. But I’ve found a few — beyond This American Life, which everyone already knows about — that really stand out:

Karina Longworth hosts this really entertaining look at “the secret and/or forgotten history of Hollywood.” This season focused on the Hollywood blacklist of the ’40s and ’50s, and it was outstanding. This isn’t just one of the best podcasts online, it’s one of the best things online, period.

The Vanity Fair writer and humor book author hosts this really unpredictable show that includes interviews with people like David Sedaris and Bill Hader, along with segments with titles like “Colonel Sanders Babbling” and “NPR Fan Fiction.” Really fun stuff.

This is billed as “a stage show and podcast in the style of old-time radio,” and that’s exactly what it is, with pulpy stories about a marshal sent to protect Mars, ghosts, detectives, and time travel. Regulars include Paul F. Tompkins, Paget Brewster, and Josh Malina, along with lots of famous guest stars.

This is hosted by comedian/writer Michael Ian Black and actor Tom Cavanagh (his old castmate from Ed, currently on The Flash). The title says it all, really: The two guys sit around and eat snacks and talk about them!

I’ll have a lot more in the future, but that’s a good start.

Safety Begins with You!

I think too many people spend too much time looking down at their phones and tablets and not watching where they’re going. They deserve to walk into poles and fall into water fountains. So I like this L.A. Metro subway safety ad, even if it’s a little … extreme:

Not sure why Joan comes apart after being hit. Maybe she didn’t drink enough milk?

National Picnic Month

I have not been on a picnic in … wait, have I ever been on a picnic? I can’t even remember. If I have, it wasn’t one of those lay-a-blanket-down-in-the-park type of scenarios. I do have a memory of eating on a picnic table a few times, but it was when Carter or Reagan was president.

But hey, July is National Picnic Month! Here are three recipes to try if you want to make the picnic just a little healthier, including a mayo-free potato salad.

What, you don’t care about being healthier? Here’s an old-fashioned potato salad recipe that uses lots of mayo and eggs, and here’s one from Rachael Ray that has yellow mustard and pickle relish along with the mayo. Throw in some corn on the cob with Parmesan cheese, some cold brews, and some fireworks, and your Fourth of July is all set.

Upcoming Events and Anniversaries

Independence Day

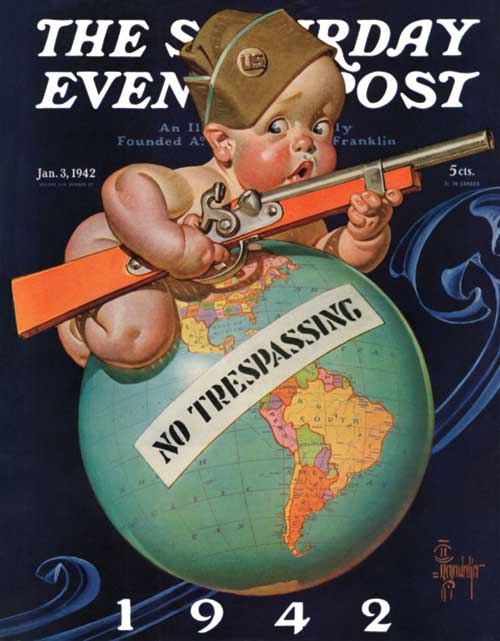

Take a look at some of our favorite Saturday Evening Post Fourth of July covers going back over 100 years.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams die (July 4, 1826)

Yup, two of our Founding Fathers died on the exact same day. And not just any day, it was The Fourth of July.

Chicago Black Sox trial begins (July 5, 1921)

Eight players from the Chicago White Sox (later nicknamed “The Black Sox”) were banned from baseball for cheating in the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds, even though they were acquitted of criminal charges.

P.T. Barnum born (July 5, 1810)

There’s evidence that the first half of the Barnum & Bailey Circus duo never actually said “There’s a sucker born every minute,” but you can still get some lessons in hype from him.

Donkey Kong released (July 9, 1981)

You can play various versions of the game for free online.

Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” exhibit opens (July 9, 1962)

The artist showcased the work in his first one-man art show as a fine artist at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

America the Smug

The views expressed here do not represent the opinions of The Saturday Evening Post.

Dear Reader: In an election year, one hears many disparate views. But no politician would dare challenge the most sacred tenet of our belief system, namely that American is the greatest nation on Earth. For that, you need to go back to outspoken midcentury theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, best known for having the Serenity Prayer adopted by Alcoholics Anonymous. The following is his essay published in the Post on November 16, 1963:

America the Smug

By Reinhold Niebuhr

Perhaps our gravest fault as a nation is our exalted sense of American virtue. We see the United States as something unique in the world, a nation whose concerns soar above petty national ambitions, whose generosity and goodwill are unequaled. God, we assume, is invariably on our side, thanks to a special covenant with the Almighty.

In one of his books, Sen. Barry Goldwater ^v e voice to this feeling. “We are the bearers of Western civilization, the most noble product of the heart and mind of man. . . .” he said. “Providence has imposed upon us the task of leading the free world’s fight to stay free.” The Republican presidential contender was expressing not merely his own patriotism but also a notion deeply rooted in our history and national character.

This sense of special virtue—with its dear implication that disagreement with us is tantamount to godlessness—offends our allies and affronts the weaker peoples of the world. It tends to obscure the fact that we are actually a normal country, normally seeking our own interests. And it greatly impedes our legitimate and worthwhile endeavors as the world’s most powerful nation.

The news of the day illustrates our moral pretensions and their consequences. When India, for example, asked our help in building a desperately needed steel mill, strong opposition arose in Congress. The mill, congressmen complained, was to be owned by the Indian government, and our aid. therefore, would serve to encourage socialism. The congressmen gave no weight to the Indian feeling that a measure of socialism is beneficial, given India’s problems. In effect, the congressmen were saying that no matter how desperate the need, the Indians would have to follow the American economic pattern or do without its aid. The Indians chose to do without. Tactfully they withdrew their request. And the future prosperity of the Indian economy which is important to the free world, was correspondingly impaired.

Or consider our relations with the new Europe. In the years following World War II the United States stood as the sole protector of Western Europe against the Soviet threat. The Europeans then were weak and could not defend themselves. Today, thanks in part to U.S. assistance. Western Europe is strong and vigorous. It not only is able to assume a larger share of its own defense costs but wants to make its own defense decisions. To the United States, the idea is unthinkable. We have grown so accustomed to dominance in European affairs that we cannot bear to relinquish the role. We fume at our “uncooperative” allies. We paint General de Gaulle, who embodies the new European spirit of independence, as something close to sinister. To a large degree our reaction stems simply from violated self esteem.

We were born with a sense of having a virtuous mission. Thomas Jefferson expressed it succinctly and admirably: “We exist and are quoted as standing proofs that a government, modeled to rest continually on the whole of society, is a practical government. As members of the universal society of mankind, and as standing high in our responsibility to them, it is our sacred duty not to blast the confidence that a government based in reason is better than one of force.” These sentiments, a typical expression of 18thcentury liberal idealism, claimed more democratic uniqueness for our Government than it possessed. For the nations of Western Europe—including Britain, whose government we had mistakenly defined as an absolute monarchy—were slowly developing democratic institutions and changing into constitutional monarchies. Certainly this exaggeration was excusable in Jefferson’s day. America was a weak infant, and to keep its self-esteem in a world of old and powerful empires, it had to believe that it was new, different and better than any other country ever founded. Jefferson the idealist was enough of a realist, however, to see the potential national domain in the wide open spaces of our virtually uninhabited continent. He engineered the purchase of the Louisiana territory from Napoleon and prompted the Lewis and Clark exploration of the northwest. Nor did Jefferson’s idealism in any way cloud his practical sense of power. “We must marry ourselves,” he said, “to the British fleet and nation.” Already self-interest and virtue were thoroughly entangled in our national character.

The normal expansive impulses of a young nation and the land hunger of our pioneers began to press against all the vestigial European sovereignties on this continent. We risked war with Britain for the sake of Oregon and had a war with Mexico for the sake of Texas. Significantly, we veiled this expansive impulse under the concept of “Manifest Destiny.” “It is our Manifest Destiny,” said the diplomat John Louis O’Sullivan in 1845, “to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” Our sense of virtue, in short, was both a spur and a veil for our sense of expanding power. Thus early in the 19th century we laid the foundation for a confusion about the relation of our power to our virtue. We have never quite overcome that confusion. It still troubles us in the days of our great power, and lies at the base of what the English scholar Denis Brogan has denned as “the illusion of American omnipotence.”

The real conflict between our sense of virtue, power and responsibilities on the one hand, and our normal concern for the national interest on the other, did not begin until the First World War. The war was our first encounter with the forces which were to lead us to the pinnacle of global responsibility. The encounter, fittingly, occurred under the last of our Jeffersonian idealists, Woodrow Wilson, who thought that America was “the most unselfish of the nations,” and was elected for a second term with the slogan “He kept us out of the war.” Idealism, however, had little to do with our entry into the war. Rather, it was in our national interest that Britain keep her influence in Europe; our peace depended on the power of the British navy. The nation was only dimly conscious of this fact, and Wilson never explicitly acknowledged it. Once embarked on the war, he defined it idealistically as a war “to make the world safe for democracy.” His most cherished object was the League of Nations.

America reacted to this first venture in world politics in almost neurotic proportions. The idealists were naturally affronted with the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles. The nationalists scorned the peace and the League because our national interests were not sufficiently protected. The period between the two world wars proved only to be a long armistice; and in the long “interventionist” debate our nation tried desperately to escape its obvious role in the world and to crawl back into the now impossible continental security. The nationalists and the idealists formed a coalition against involvement so strong that we might not have made the plunge into World War II had the Japanese not made the decision for us by attacking Pearl Harbor.

During the interventionist debate í was a member of a committee advocating an affirmative responsibility toward the war in Europe, The very name of the committee was an indication of our moral ambivalence. It was the ‘Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies.’ The very name of the committee would have outraged Woodrow Wilson; but it was shrewdly designed to avoid his too consistent idealism. Many Americans were not willing to admit that the Nazis had to be defeated at whatever cost, because both the national interest and a human value were at stake.

The Second World War raised the old tension in our national soul—between our senses of virtue, power and responsibility—to a global dimension. For we emerged from the war the strongest democratic nation. The war had increased our productive capacity and had impoverished Europe. We were cured of our old nostalgia for innocence at the price of irresponsibility; the very degree of our power made our responsibilities all too clear. In 1946, American mothers were pleading to “bring the boys home by Christmas,” a sentiment that resulted in our leaving our potential foes, the Russians, in possession of much of a defeated and devastated Europe. But by 1948 we were engaged in the Marshall Plan, and our wealth and power were turned to European reconstruction. We had learned our lesson. A powerful and wealthy nation must assume responsibilities commensurate with its power and wealth.

But the old problem of virtue and power assailed us in a new way. We claimed a unique virtue for a policy which actually was an act of wise self-interest. We almost spoiled the virtue of our prudence by remarks such as that of the politician who crowed, “The Marshall Plan was the most generous act ever undertaken by any nation.” That claim prompted derision even among our allies and friends in Europe. The Marshall Plan was not generous but prudent. It saved the European continent for democracy, when all of its wealth, skills and talents were imperiled, and when their loss would have meant our isolation.

The fact is that a nation with a sense of virtuous mission finds it difficult to understand that the moral norm for nations, as distinct from individuals, is not generosity but a wise self-interest— a self-interest that lies somewhere between the parochial and the general interest. Since the Marshall Plan we have wisely sought to help the nations of Africa and Asia up the steep path to modern industrialism and consequent freedom from age old poverty. Our foreign aid program does not exceed one percent of our gross national product and is only a tenth of our total defense budget. Yet it is an unpopular part of our budget, perhaps because there is no bloc of voters to defend it. We constantly worry that we may have become “too generous,” letting the designing nations of Europe and the world take advantage of our pure hearts. However, we are dealing here with moral realities, and moral realities do not fit neatly into the usual moral categories of “unselfishness” and “generosity.” Foreign aid involves relations in which our interests are inextricably intertwined in a whole web of mutual interests.

Many circumstances, in fact, make it difficult for us to view our responsibilities soberly, without undue pretensions of unique virtue. Our living standards, for example, arc twice those of the more advanced nations of Europe and are beyond the dreams of avarice of the Asian and African continents. Further complicating the problem of keeping our national self-esteem in sober bounds is our outrage over the “ingratitude” of widespread anti-Americanism. Some of this anti-Americanism is prompted by envy. Some of it, as in the case of Gaullist France, may be prompted by aspirations to national glory. Some of it is also due to the fact that no human agent is ever as wise or as disinterested as he thinks he is. Criticisms will be directed at us because of our errors and because of our achievements.

Since we are bound to occupy the eminence of world hegemony for a long time (if the uneasy peace of a “balance of terror” does not make an end of us and our civilization in a nuclear catastrophe). We must be prepared to exercise our power with more soberness than our original sense of virtue inclines us to. We have become one of the two “super nations” in the modem world; and the only one of the two which must deal with the great and small allies in the spirit of free accommodation of competing interests. We must be prepared to be unpopular, even if our decisions in crucial issues are right, and to accept unpopularity because our decisions may be wrong. For we are not as omniscient as we seem to be in the day of our seeming omnipotence, and certainly not as virtuous as our whole tradition has persuaded us that we are.

An end to arrogance

One of our chief problems will be to avoid what has been called the “unconscious arrogance of conscious power” as we deal particularly with our great allies, many of them in Europe. Their greatness cannot be diminished by the new magnitudes of modern “super nations,” and their memories of past glories and experience of present frustrations are bound to lead to jealousies.

The moral problems of our national life are so complex that they cannot be understood by the simple categories of good and evil—of “selfishness” and “unselfishness”—which individuals recognize. It is ironic, in view of our early passion for displaying the purity of our virtue, that today the responsibilities of our role should include the mounting of a nuclear deterrent, thus involving us in the proleptic guilt of a nuclear catastrophe. The moral ambiguity of the political order, which we have desperately tried to veil or to ignore, has been raised to the nth degree in our experience of power and responsibility.

Our best chance of avoiding the moral pretension that besets us is to analyze the circumstances that have brought us to this perilous condition. Two points are especially significant. First, it is our power, not our unselfish virtue, that makes the survival of Western civilization depend upon our own survival. Second, the degree of our power is not the fruit of the virtue of our own generation—the generation that wields the power. We are strong because many “gifts of Providence” have contributed to our power. Among them are a hemisphere richly stored with natural resources; the fact that the expansion of our nation coincided with the industrial revolution, enabling us to unify a whole continental economy; and, of course, the fact that the Civil War preserved our national unity.

By steadfastly keeping these two points in mind, we can prevent such virtue as we possess from exuding the sweat of self-righteousness.

The World War II Struggle That Time Forgot

As a child in the New Jersey suburbs in the 1970s, I grew up hearing harrowing tales of the Holocaust, often while playing in the backyards of the grandchildren of survivors. In the summer, glimpses of numbered tattoos peeked from loose clothing, permanent proof of what this generation had gone through, sometimes leading to reluctant conversations against the watery backdrop of sprinklers, iced tea, and swimming pools.

I was raised in a non-Jewish family in a largely Jewish suburban neighborhood. Come December, our house was among the few on the street with a Christmas tree. The holiday season was when our Polish-born uncle Eddie, who had married into the family via my aunt RoseAnn, would come to visit. He too had stories of the Nazis. The most vivid was his escape from a work camp by hiding inside the wheel carriage of a departing train.

Even with his brush with the Nazis, I think we dismissed his stories because we knew they were not Jewish tales; they lacked the gravity of the stories our neighbors’ grandparents told. Nothing in our schoolbooks backed up his description of the Polish experience during World War II.

The stories stopped when I was 12, the year my uncle divorced my aunt. Though I would see him briefly at my aunt’s and my father’s funerals, 34 years would pass before I would spend any serious time with him, this time in his hometown of Warsaw.

My uncle and I share the same birthday, and as he aged, I decided I would try to use the day to reconnect by calling him. The journalist in me, having covered horrific events in today’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, also wanted to sort out his time under the Nazis, always knowing there was more to it than what he told us. My uncle was a teenager when the war ended, and, at 86, he is among the youngest of those still able to recall a period rapidly slipping out of living memory.

When I called my uncle on our shared birthday in early 2014, mentioning I wanted to formally record his life in Poland, he told me he would soon be back in Warsaw “for the 70th anniversary of the uprising.”

He added, “The government is inviting me to come and be honored for being in the resistance.” I thought for sure my uncle had gone senile. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was in 1943, and the 70th anniversary commemorations had come and gone. My uncle went on to describe something I had never heard of before: the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, in which he fought as part of the underground resistance.

No, my uncle was not senile. I was simply undereducated. The Warsaw Uprising — when the entire capital rose up against the Nazis, resulting in the destruction of 85 percent of the city — was simply not something Americans are taught. It is instead the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising that we learn about in our schoolbooks and via broadcasts like Holocaust and movies like The Pianist.

I was newly proud of my estranged uncle, and I vowed to travel to Poland with him, to hear the stories where they happened, rather than in a New Jersey living room. Not only had he escaped the Nazis, but he had also fought against them in Poland’s resistance, or Armia Krajowa.

Last summer, in Warsaw, at the sites and memorials where contemporary Polish politicians celebrated Eddie and his surviving compatriots [see “Freedom Fighters”], my uncle’s stories began to align into proper sequence. He is one of perhaps 3,000 surviving Polish resistance fighters, about 700 of whom live outside of Poland. While he now goes by Edward Sutton, his Polish name is Edward Sucholski. His resistance code name was Czarny, or Black. One story my uncle told me was of a shootout on Brzozowa Street near Warsaw’s Old Town close to the Vistula River, at some point on August 31, 1944. From a second-story window, he and another resistance fighter battled German soldiers who were in the basement of a nearby building. Few resistance soldiers had weapons, but my uncle had a Schmeisser, an automatic pistol. My uncle said he and the other fighter were fighting from the second floor of what was called the professor’s house, an assembly site for the resistance. “I was shooting from 200 feet away, but I never knew if I killed anyone.”

He and the other fighter retreated. My uncle remembers fleeing along the Vistula into a sewer with other fighters, Germans throwing grenades in after them. He told me, “After that I couldn’t hear for a couple of days from the explosions.” Inside the sewers, there were masses of people, sloshing through the water. “We were just so many of us,” he said, adding, “we were lucky we came out alive.” He made his way to the Kampinos Forest, where he gave up his gun to another resistance fighter.

After the uprising had been put down, my uncle surrendered and was loaded into a cattle wagon, under the watchful gaze of “a German soldier on each rooftop with a machine gun,” he said. Dachau was his first stop, yet he downplayed this, saying he and his father were there only a week “for sorting” before moving to another work camp in Germany. My step-aunt Teresa who came with us explained, “When you came in to the camp, you went one of two ways: either up the chimney or to work. Thanks God, Eddie went to work.”

It was how he, his brother, and his father survived.

They escaped on Christmas Eve, 1944. “We lied on the beams of the train, trying to make ourselves as invisible as possible,” he said.

I wondered if the date was chosen with the knowledge that the Germans would be drunk. Instead, he said, “No, it was snowing, so we knew they wouldn’t take the trouble to look for us.”

My uncle didn’t make it back to Poland. The train only got him to Augsburg, near Munich, ironically close to Dachau where he had first arrived. There, he and his father pretended to be displaced German Poles. After the Americans liberated this part of Germany, he went to Italy, joining the Polish army there, and later was sent to the United Kingdom. After the war, he had the option to relocate to Palestine, a surprise to me as he is not Jewish, but young Catholic Poles were relocating to orphanages there. In 1951 he finally found true freedom here in the United States, arriving via an El Al flight from London to New York’s Idlewild Airport, now known as JFK.

The intermingling of Jews and Catholics was apparent as we visited his street, inside of what had once been the Jewish ghetto. The Chinese Embassy now sits over his long gone childhood home on Franciszkanska Street, near the ghetto dividing line. Warsaw was almost 40 percent Jewish then, but “they took the Jews away from us, we weren’t allowed to live with them,” my uncle said, including his first girlfriend, Rifka, whose fate he does not know. He lifted his hands above his head, curling his fingers into balls, and twisted them back and forth, saying, “They built a 10-foot wall around them and covered it with barbed wire.” Though he had revisited Poland many times, he had not returned to his street since 1944.

Why is their historical struggle shrouded in such darkness? Pawel Ukielski, the vice director of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, blamed a variety of circumstances. “The Warsaw Uprising was not convenient for anybody to talk about for a long time,” he said, explaining that the Russians — expected to come to the assistance of the resistance fighters — instead camped outside of Warsaw, allowing the Germans to destroy the Polish capital. Their cold calculation was that a devastated country would be easier to occupy at the end of the war. Western Europe and the United States don’t come out much better in this story; they also refused to recognize the exiled Polish government after the war, since the Allied plan was to cede what was left of Poland to the Soviets.

Why is their historical struggle shrouded in such darkness? Pawel Ukielski, the vice director of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, blamed a variety of circumstances. “The Warsaw Uprising was not convenient for anybody to talk about for a long time,” he said, explaining that the Russians — expected to come to the assistance of the resistance fighters — instead camped outside of Warsaw, allowing the Germans to destroy the Polish capital. Their cold calculation was that a devastated country would be easier to occupy at the end of the war. Western Europe and the United States don’t come out much better in this story; they also refused to recognize the exiled Polish government after the war, since the Allied plan was to cede what was left of Poland to the Soviets.

Today, the importance of remembrance has finally trumped the silence over collective guilt. “We are proud that Warsaw was the city of two uprisings. Both of them were unique,” said Ukielski. “We know what happened to Warsaw during the Second World War. It lost almost half of its pre-war population. It lost the whole Jewish population. It was a great loss, a loss of part of our identity. So this is not the question that one such loss should be better known or worse known, we want both of them to be known all over the world.”

I have found, after spending time with my uncle in Warsaw who lived to see both uprisings, that I too know them both better than I ever would have before.

Editor’s note: Portions of this article were previously published in Tablet magazine.

Click here to read a true story from the Post archives about the heroic warriors of the Polish underground.

—

Michael Luongo’s “The World War II Struggle That Time Forgot” won a 2015 North American Travel Journalists Association Gold Prize.

Is World War I Relevant?

“Is anything about World War I even relevant today?”

I’ve often been asked that question since I began this blog last fall. I’ve asked it myself. Is there anything we can learn from 100-year-old wartime experiences?

After reading “War and Hallucinations,” by Corra Harris, I can now answer with an assured yes. Because Harris, though writing 100 years ago, describes the challenge we still face in coming to terms with war and terror.

Back in 1915, American newspapers continued to publish atrocity stories from Europe. The German army was accused of mass executions, rape, and slaughtering children. Journalists couldn’t confirm or deny the reports coming out of Europe, but that didn’t prevent American newspapers from repeating the stories.

Harris didn’t believe the horror stories. Rather than recount them again, she gave her opinion of where they came from, and why so many people believed them. The war, she wrote, had caused the people of Belgium, France, and England to lose some of their sanity:

From the day I entered the war zone till this one upon which I take my departure from it I have been aware of a certain psychic condition, difficult to describe yet so powerful that no one can escape its influence … as if all thought had lost its shape, and reason was no longer reasonable. As if all men and all women were somnambulists walking in a black dream.

They speak with calmness of things so horrible that one is amazed that they do not shriek and wring their hands. And one is still more amazed at having the power to listen with calmness. We see terrible sights, we hear of them, we think of nothing else, and yet we do not go mad. For where everybody is mad no one is.

The French newspapers had carried the news of thousands being killed at the front, and an unstoppable German army was marching on Paris. Fear overpowered reason. The citizens’ anxieties were fed by the terrifying stories — “hallucinations” Harris called them — from refugees arriving in the cities.

Harris described Lille refugees traveling for days, defenseless and hungry, with artillery fire from both sides exploding around them. They knew the Germans were right behind them, and they weren’t permitted to stop in towns along the way. They might collapse in exhaustion in a ditch for a few hours’ sleep, but they’d awake at a strange sound or a suspicious form in the darkness. And as they resumed their march, they picked up bits of conversation from other refugees to weave them into their own fearful imaginings.

When they finally came upon relief workers, they recounted their journeys with a vividness that reflected their terror more than their reality. “The awful thing about war for the helpless,” she wrote, was that war “is what they fear, intensified by the horrible things they have heard.”

It wasn’t just refugees. Harris remembered soldiers claiming to have seen 10,000 men killed every day in one battle. The rivers near Calais, they said, were clogged with the bodies of dead Germans. Calmer observers coming on the scene after the fighting found nothing to justify these claims. These “hallucinations” were the attempts of Frenchmen, who had led routine, peaceful lives before the war, to describe the spectacular horrors of what they’d seen.

(Wikimedia Commons)

“When 70,000 Indian troops landed at Marseilles it was incredible,” Harris added. “The sight fired the imagination, so we heard that a force of 800,000 Japanese were already on their way to join the Allied Armies. Only 800,000! You get the contagion for using big numbers from reading the papers and from listening to the average man talk. Figures, which in normal times are supposed not to lie, have become the medium of fiction in this war.”

This exaggerated language was another sign of the derangement from war, Harris wrote. “Language is … designed to convey the commonplace meanings of life.” But the Europeans were experiencing such atrocities that their minds were “completely divorced from reality, because reality itself surpasses the power of even imagination to conceive.” And language became “the war currency of a bankrupt nation. It has no value. All the lies that words can frame are floating in this atmosphere. The truth itself is the greatest fabrication of all, because it belies all we have called truth.”

Today, it’s difficult to keep a sense of proportion when we think of 9/11, the Boston Marathon bombing, or the grisly murders of captives in the Middle East. We calmly discuss these events, and even try joking about them, as if to laugh off our worries. But the uncertainty and anxiety remain because the limits of the-worst-that-could-happen have been pushed far back. Faceless enemies and random attacks have eroded our sense of what to expect, or whom to trust. When reason can’t make sense of our world, dread and fear can take over.

As Harris noted in 1915, “Every ideal by which men aspired and lived is changed. Nothing is familiar and no man is sane — because imagination rules.”

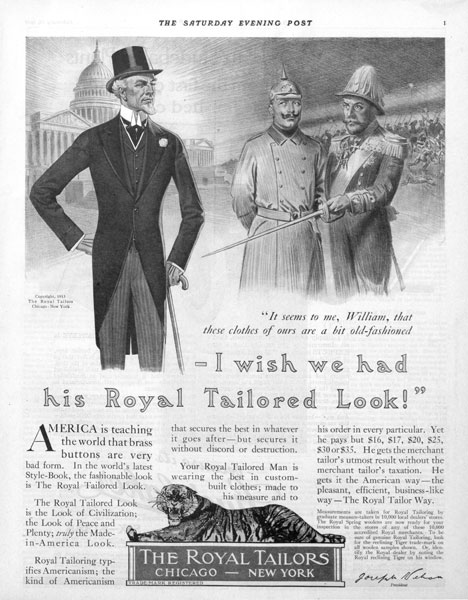

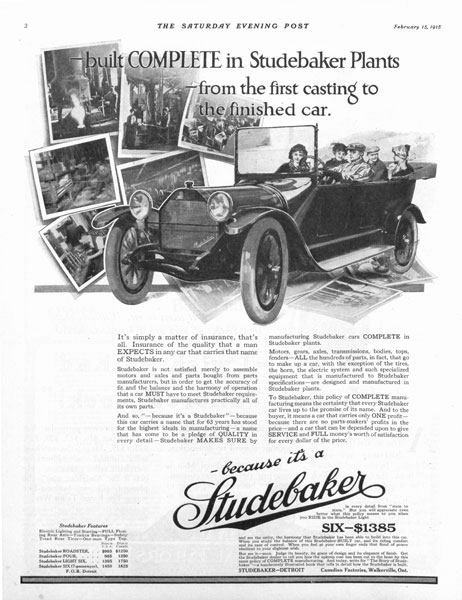

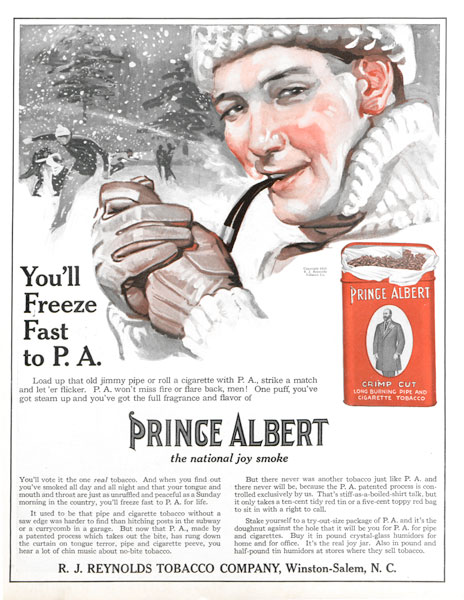

Step into 1915 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post February 13, 1915 issue.

How to Be Neutral

Why does America find it so difficult to remain neutral?

Why do we seem impelled to take sides and get involved in global politics?

A century ago, as the U.S. watched Europe sinking in the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson asked Americans to be “neutral in fact, as well as in name. … We must be impartial in thought, as well as action, must put a curb upon our sentiments, as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference.”

But when war returned to Europe 25 years later, President Roosevelt declared, “This Nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well. Even a neutral has a right to take account of facts. Even a neutral cannot be asked to close his mind or his conscience.”

This was not neutrality, wrote Post contributor Demaree Bess, and he knew what he was talking about. For the previous two years he had been living in Switzerland. The small European republic had maintained its freedom for over a century while observing rigorous neutrality, which he defined as “the state of being friendly to two or more belligerents, or at least not taking the part of any.”

The Swiss, he wrote, couldn’t understand how Americans thought they were being neutral when they were encouraging their government “to line up with one set of European powers against another set, even before a war starts.” According to Bess, Americans thought simply declaring neutrality gave them the right “to take sides violently in every conflict which occurs in any part of the globe.”

The Swiss would stay out of the war, Bess wrote, because they would not fight for the things they believe in. The only cause for which the Swiss would take up weapons — which they were ready and prepared to do — was an invasion of their homeland. “They never even discuss the possibility of fighting for an abstract principle, such as collective security, or for any distant colony … or an ally in Eastern Europe. … They have only their own little country, which they spend all their time and attention cultivating. They are prepared and willing to fight for that country, if it is invaded.”

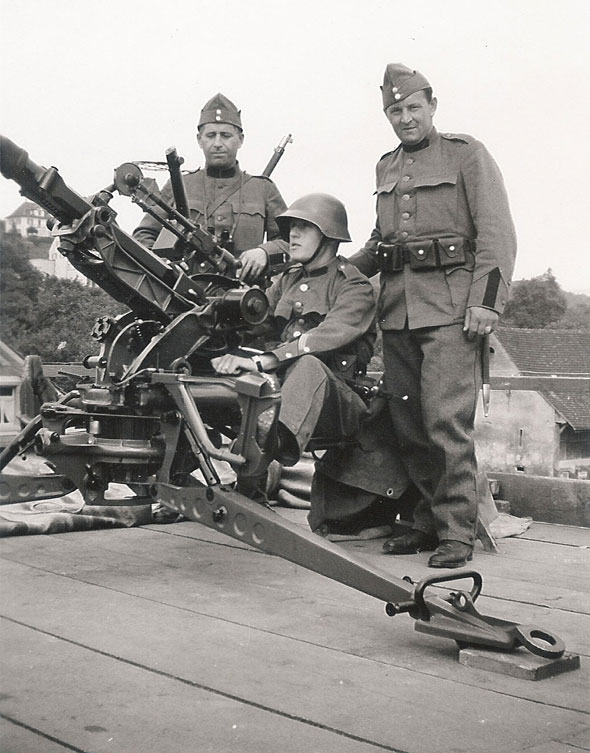

Between 1936 and 1939, the Swiss had spent $230 million to reorganize defenses. They modernized weaponry, especially antiaircraft defense and frontier fortifications. The government also increased the amount of training required of all Swiss citizens between 18 and 60 years of age. “This country of 4 million can put an army of 500,000 into the field within two days or less,” Bess wrote. When the Swiss Federal Council saw Europe sliding toward war, it mobilized the entire army. In just three days, its entire national force was ready.

Bess obviously admired the Swiss system, which, he reported, had created a “democracy united in its determination to preserve its democratic ideals as well as to keep its boundaries intact.” Reading his article, you get a sense that he thought the United States would be smart to adopt the Swiss model, and in his words “mind its own business.”

Could the U.S. have remained neutral, as its isolationists wanted? Probably not, in the long run. As much as its citizens might have wanted to stay out of the conflict, the country’s great wealth, spacious land, and open borders would have proved too tempting for the Axis, who would have found some pretext to seize American soil.

Japan was already anticipating an attack on American interests in the Pacific in 1939. Hitler, though, didn’t draw up concrete plans for conquering America, because he believed it was peopled by mongrel races incapable of defending themselves. He probably assumed that, after subjugating Europe and Russia, America’s manufacturing and agricultural wealth would simply fall into his lap.

Switzerland could make neutrality work because of several advantages America didn’t enjoy. First were its formidable mountainous borders. Admirable as its citizen army might have been, its effectiveness depended as much on the country’s alpine geography as its training and spirit. The Swiss army might have proved far less effective if it had to defend a nation as flat as Poland. Nazi Germany had, indeed, drawn up plans to invade Switzerland, but concluded that that conquering such a mountainous country wouldn’t be worth the cost.

Switzerland also benefitted from Nazi’s leniency toward the Swiss whom the Nazis considered essentially German. Hitler and his followers didn’t feel compelled to dominate the Swiss as they had the Czechs and Poles.

Besides, a small, wealthy neutral country next door offered many attractions to Nazi Germany. Switzerland provided an intelligence post where German agents could pick up Allied information. Also, several banks in Switzerland proved very helpful to Nazi officials who wanted to store their plunder beyond the reach of their own government. They found Swiss bankers more than happy to do business with them, even enabling them to store and trade stolen paintings.

Moreover, factories in neutral Switzerland, which weren’t being bombed by the Allies, could provide Germany with a steady supply of much needed steel and weapons. And, for a price, the Germans could use Switzerland’s transalpine railway to keep supplies flowing to their ally Italy.

But Bess couldn’t have known all this in 1939, when neutrality still seemed a workable response to the world war. The next seven months proved what a bad idea this policy was. One by one, other neutrals — Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Holland — were seized by the Nazis, bringing the war closer to the shores of neutral America.

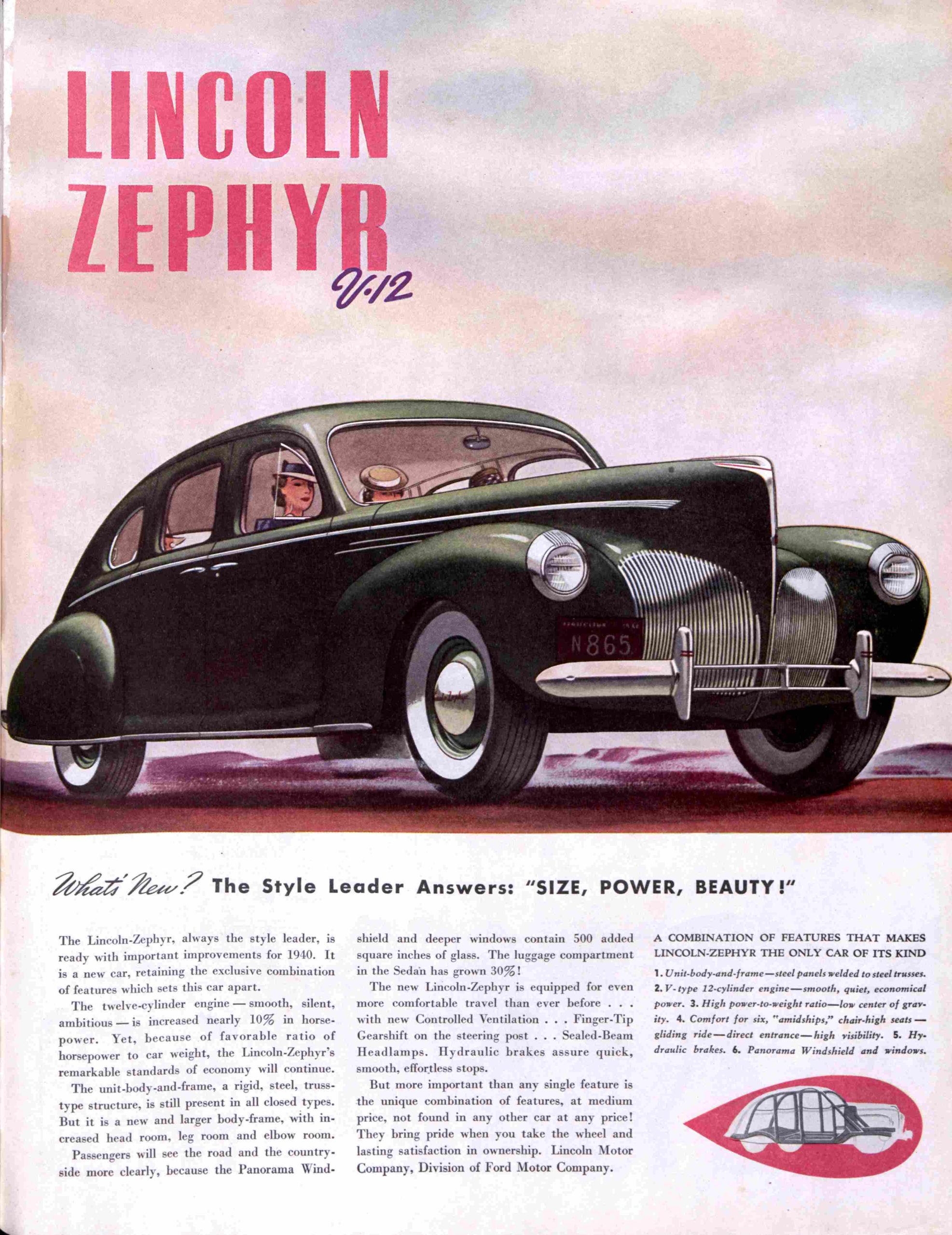

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago:

A Look Inside Germany’s First Conquest

courtesy Wikimedia Commons

By coincidence, a Post article about Czechoslovakia, the first nation conquered by Hitler, appeared just as he was grabbing up his second.

“Nazi Germany’s First Colony” appeared in the Post on August 26, 1939, the day Hitler had originally planned to invade Poland (Read full article here). But his plans were pushed back, and the issue was still on newsstands when Hitler’s armies crossed the border into Poland on September 1. The ensuing blitzkrieg, which brutally crushed all Polish resistance, had little in common with the swift, bloodless conquest of Czechoslovakia.

The Czech republic had already been reduced when Great Britain and France allowed Hitler to occupy its borderlands in 1938. The next year, he returned to grab the remaining provinces of Bohemia and Moravia through threats of invasion. United Press reporter Edward W. Beattie Jr., who was in Czechoslovakia at the time, described the curious manner of the German invasion.

After bribing a taxi driver to take him toward Germany’s advancing forces, Beattie was startled when German scouts suddenly appeared, moving rapidly, coming down the road toward him: “When we met them head-on, the driver tried frantically to turn. It was too late. The unit began passing us. The officer in command leaned out over the side of [his] scout car. I thought he was going to ask for identification but all he said was: ‘From now on in this country, you drive on the right-hand side of the road.’ The occupation was as easy as that” (collected in They Were There: The Story of World War II, edited by Curt Riess, Garden City Publishing, 1945).

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from this week’s Post, 75 years ago:

There was no violence, no popular uprising, no guerilla warfare. The Germans simply took up residence in the capital city, Prague, and began appropriating what they wanted. Resistance was reduced to futile gestures, like the one Beattie recounted when he and other foreign correspondents had visited a nightclub. Taking advantage of their journalistic immunity, the reporters ordered the band to play “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” “Over There,” and other Allied songs from the First World War. In a scene reminiscent of the movie Casablanca, the songs made “a couple of dozen German officers at other tables [get] more and more restless.

“Finally two officers a short distance away pounded for silence,” Beattie wrote, “and one of them came over and demanded that we stop ‘insulting the German army.’ Later in the evening, when everyone was drinking pretty heavily, he drew me to one side and said, ‘You don’t think we like this sort of thing too much, do you? For God’s sake, let us try to make this occupation as decent as possible.’ (The army’s part in the occupation was decent in every way. Of course, the Gestapo and the S.S. arrived later.)”

Beattie’s observation was echoed by the Post’s foreign correspondent Demaree Bess: “Greater Germany has planted her first colony in the heart of Europe. Bohemia and Moravia … have become as much of a colony as any island in the South Seas. The Czechs have assumed the inferior status of natives. … [They] do most of the work and the Germans pull all the wires.” It was the Germans’ goal to turn the republic into an efficient workhouse and profit center for the German Reich.

In these early days, they were careful not to make their exploitation too obvious. As Bess wrote, the Germans still hoped to win the cooperation of Czech workers and industrialists. At least that was the intent of the new government the Germans set up in Prague. Their biggest obstacle, it turned out, was other Germans — the Gestapo, the S.S., and officials of the Nazi party.

Nazi officials descended on Prague with the sole purpose of enriching themselves. They were soon disrupting Czech manufacturing by raising production quotas while limiting managers’ profits. The Nazis were further disrupting the economy by ruthlessly exploiting the Jews.

“When the Germans entered Prague without warning last March, they made it clear at once that life would become intolerable for Jews,” wrote Bess. “Thousands therefore went to the German secret police to apply for permission to leave the country. They were told their applications could not be filed until they had made ‘satisfactory arrangements’ with a Nazi-controlled bank, which demanded full powers of attorney over their property.”

The full savagery of Nazi domination was still in the future. But already, under German rule, life was becoming miserable for the Czechs. Consequently, Bess reported, “I know of only one European country today whose people, in very large numbers, actually desire a general European war. That country is the German protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Czechs say they have discovered that some things are worse than modern war.”

They were about to find out that modern war could be much, much worse.

Listen to President Roosevelt’s August 28, 1939 address to the Herald-Tribune Forum. In talking about the need for peace, he is already distancing himself from the old policy of peace by appeasing Hitler.

Listen to a radio speech on the BBC given on August 27, 1939 by Jan Masaryk, the former head of the Czech nation. He had seen his country betrayed by his allies, Great Britain and France, who allowed Hitler to seize first the border regions of Czechoslovakia, then the entire nation, rather than go to war with Germany.

Listen as Adolf Hitler justifies his invasion of Poland to an ecstatic Reichstag.

Meanwhile, as you’ll hear, Great Britain and France are hurriedly summoning their governments to respond to Germany’s aggression.

Did the Post See World War I Coming?

In the months following the start of World War I, government leaders on both sides expressed surprise and dismay to find themselves at war. Nobody, they said, had expected it, and certainly nobody wanted it. A Serbian terrorist had simply shot the heir to the Austrian empire. The next they knew, Austria had declared war on Serbia, which prompted Russia to mobilize its army. This caused Austria’s ally, Germany, to declare war on Russia. France then declared war on Germany, and soon Great Britain joined in, followed the next year by Italy.

June 20, 1914 © SEPS

Surely someone must have seen “The Great War” approaching. How could something big enough to cause four years of fighting, 10 million deaths, and the end of three monarchies simply show up without any warning?

Americans were baffled. They had been paying little attention to Europe since the U.S. had forced an ailing Spanish empire to relinquish its Cuban and Philippine colonies. Generally, Americans were happy to ignore Europe’s problems and focus on their own prosperity.

The U.S. in 1914 was still a principally rural country, which had changed little since the 19th Century. The average American lived a horse-powered life on a farm or in a small town, and what he knew of the world came from a local newspaper or from magazines arriving by mail. If he was among the two million subscribers to the Post, however, he might not have been as surprised by the outbreak of war as were the crowned heads of Europe.

Just one month prior to the start of the war, Post journalist Will Payne reported from Europe, where he had been researching finances on the Continent. He learned that Italians paid more taxes than any other nation in Europe—and were glad to do it. Taxes were essential to maintaining their army, Italians told him, and preventing France and Austria from returning to rule them. In “Barracks and Beggars,” Payne reported that the people of Italy would pay their last cent and put every one of their men in uniform before submitting again to foreign domination.

When Payne crossed the border into France, he found the same militaristic attitude, but in this case the cause for concern was Germany. The French overwhelmingly supported the stiff taxes that were building up their army, though it consumed nearly half the national budget. Nor did the French object when the government extended the length of mandatory national service from two to three years. A banker told Payne, “I was in favor of that, and so, you will find, were a majority of Frenchmen. Look at what they are doing in Germany, with their new regiments and extraordinary war tax. If they arm, we must arm. It is the price of our life. Germany hates us as much as ever. To disarm would be to commit suicide.” Payne added, “nearly all Frenchmen talk the same way.”

June 20, 1914 © SEPS

The French believed that military training not only kept the country strong but gave pride to its young men, as well as an appreciation of order and hierarchy. “At least a dozen men, first and last, emphasized the point that it taught obedience to authority; or, as one of them more accurately put it, ‘It teaches people that some must command and some must obey.’”

It was a similar story in Berlin, where Payne found “the German businessman speaks of his war taxes as insurance—that is, he regards the tax receipt as a policy of insurance that for another twelve months no British cruiser will shoot the roof off his warehouse.”

The militant spirit had infected Great Britain as well. The British feared losing the global dominance of its navy, particularly since Germany had begun expanding the number of warships. And so Parliament was continually increasing the budget to expand the Royal Navy. But a naval victory over Germany would be useless, the ministers argued, unless a strong, well-drilled British army could secure victory on land as well. So the army’s budget had to be increased as well. Meanwhile, “elderly gentlemen in possession of pleasant jobs and comfortable incomes” insisted that the young men of England required military drill and discipline to guard their character and protect them from dangerous social ideas.

June 20, 1914 © SEPS

All the nations of Europe, Payne found, were locked in an ever-escalating spiral of military preparation. Every country feared the imminent domination by another.

So, for example, the German Kaiser would call on his nation to ensure its security with more men for its army and more millions for weapons. Russia and France would then call up more men for service and hike their taxes to regain the balance of power. And so Germany would launch yet another campaign to gain a strategic edge.

“Militarism is costing Europe about two and a half billion dollars a year to support in idleness some five million able-bodied men who might be productively employed,” Payne wrote, “and its path still pursues an upward spiral.”

He recognized the militant attitude would seem strange to readers of the Post. “Americans think of war about twice in a decade, and then with no very keen interest,” he wrote. “In Europe they think of it all the time.”

It wouldn’t have surprised him that, when the governments of Europe declared war, the news was welcomed by delirious crowds, who jubilantly marched up and down the streets of Berlin, Paris, St. Petersburg, and London. Men not already in uniform rushed to join the great cause, which would liberate their country, at last, from the perennial threat of some neighboring country.

The leaders of Europe’s government might have been surprised that the war came as it did, when it did, but they shouldn’t have been shocked by the war itself. As the Post had been reporting, they had been stoking the enthusiasm for it for years.

A New American Isolationism?

For the past century, the United States has frequently gone to war in the interests of freedom and democracy–often with the unstated (but not necessarily secondary) purpose of protecting our sources of oil or for access to populations who would buy our goods or services.

But the costs lately have become overwhelming, whether measured in cold, hard cash or in lives lost. America has lost its appetite to serve as policeman in the earth’s most horrific trouble spots. We just want to be left alone.

March 2014 marked the first month in more than a decade without a single American combat casualty anywhere in the world. For the vast mass of the American people, getting out of military entanglements is now the expectation rather than some vague hope. After two wars stretching back 13 years, American sentiment has once again tilted toward the isolationism that marked the end of the First World War. “[That conflict] was followed in the ’20s and ’30s by something that…was in fact a rejection of a certain role in the world,” says Robert Kagan of the Brookings Institution and a foreign policy advisor to Senator John McCain’s presidential campaign. “It wasn’t just, ‘Let’s have a little time out here.’ It was, ‘We are not going to be doing that.’”

In fact, it would take a challenge to our very way of life–in the form of Hitler, Mussolini, and that dastardly backdoor attack on Pearl Harbor–to draw us into World War II. And we never really emerged. The Korean War followed just a few years afterward, then it was on into Vietnam, and almost before we all realized what happened, we were on to the Balkans and Sarajevo; the Middle East, Iraq and Afghanistan; and now there’s Syria and Crimea and Ukraine.

And each such adventure has its own price tag. Iraq, a country from which we have already technically departed, is still costing us $3 billion per year. The overall Department of Defense budget totals some $496 billion, or 13.6 percent of the total federal budget today–and that’s with a rapidly shrinking military.

Compare these numbers to those of the Korean War, which cost us $30 billion ($262 billion in today’s dollars) or less than one-third of the cost of the post-9/11 war on terror that includes Iraq and Afghanistan, which the non-partisan Congressional Research Service puts at $859 billion.

With 20/20 hindsight, it’s beginning to look increasingly like our all but universally accepted role as the world’s policeman really peaked sometime during the Korean War. Then began a long, slow descent, largely perceptible only to the most astute observers positioned outside the Beltway. When John F. Kennedy sent us swaggering into the Indochina Wars at the very moment a far more nimble Charles de Gaulle was already extricating France, we were still operating under the assumption that America somehow had a higher calling we needed to fulfill. It seemed only America had the might, and the moral will, to prevent the rapid spread of that evil virus called communism across Indochina, into Thailand, down the Malay Peninsula and across Southeast Asia.

As it happens, I was present as a journalist to witness the final days of America’s foray into Southeast Asia. The final days and weeks of the takeover of Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge were not amusing. Seeing the conflict at this late stage, one forgot the original point of the American mission, to serve in a police capacity in this region.

But was that even an appropriate use of American power and influence? Neither in Korea nor in Vietnam nor in any other police action since–certainly not in Afghanistan or Iraq–has America had the kind of influence over the outcome envisioned at the start of our engagement. Our role was always presented to the public as a limited exercise: Act the role of the good cop, oust the bad guys, clap them in jail, then get the heck out of Dodge.

Of course, it’s never quite worked that way, and we have never learned our lesson. The failure derives not from a lack of good faith, but rather from a lack of vision. When we entered each of these rabbit holes, we never had a real understanding of how we’d emerge. As is clear now, the end game is in most respects far more significant than the entry point.

But if the American people have come full circle in the past century, arriving today at a reluctance for combat that mirrors post-World War I isolationism, many nations still look to the U.S. to play the role of global cop–if only because no other nation has the might or the will to play such a role. “I fear that what is going on now is that Americans are quite understandably not only tired of the burden, but they no longer understand the reasons why we even took on this burden in the first place,” Kagan says.

About those reasons: Sixty years ago, The Saturday Evening Post article “Can We Remake the World Without Going Broke?” observed that the nation’s Mutual Security Program, newly signed into law by Truman with bipartisan support in Congress, was staking the future of the American economy upon “the hope of revolutionizing the non-Soviet world.”

The piece continued: “This program pushes American military frontiers far out into Europe, Asia, and Africa. It consolidates an American pattern for reorganization of the entire non-Soviet world through combined military, economic, financial, and social measures.…It appeals to those who believe that ‘sharing our wealth’ is speeding up some form of world government.…On the other side, it appalls those Americans who are chiefly concerned with the radical changes which ‘mutual security’ means for the American traditional system: indefinite conscription of our young men, Federal expenditures greatly in excess of revenues, unparalleled taxes which are certain to increase, the overhanging threat of monetary inflation which already has reduced the purchasing power of the dollar by more than half.” (For more selections from the Post archive, see page 37.)

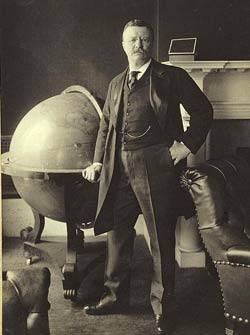

Teddy Roosevelt And World War I: An Alternative History

It’s impossible to declare precisely what would have happened had Theodore Roosevelt been re-elected in 1912. But throughout his career, he was interested in global politics and spreading American influence. There is no question that, as president in 1913, he would have taken a far different course during World War I than the one taken by Wilson. Here’s how we think it might have happened.

In this alternative history …

• America enters World War I two years earlier.

Teddy Roosevelt could never sit by and watch a fight: he either had to break it up or join in. So when the old Rough Rider hears, in 1914, that Germany has marched over neutral Belgium to attack France, he commits our resources, and then our soldiers, to the Allied cause.

• World War I ends two years sooner.

It takes almost a year to build the ships, arm the troops, train them, and land them in France. By late 1915, though, the American Expeditionary Force of 10 million soldiers is fighting alongside the French and English armies on the Western Front. Even with the wasteful tactics of the European generals, which sometimes wipe out thousands of soldiers in hours, the Allies put enough pressure on the Germans to crack their defenses. The Kaiser’s army falls back, across France, into Germany, with the Allies in pursuit. As winter begins in 1916, the Germans are asking for peace terms.

• Adolf Hitler never comes to power.

The German people see their army in retreat, and the Allied armies occupying their cities. They blame their defeat on the military adventurers who run the Kaiser’s government. When young Adolf Hitler starts proclaiming the invincibility of the German army, and the need to prepare again for war, few Germans are interested. Mostly, they’re relieved when the occupying Allied forces arrest him and keep him in a French prison. Without him, the National Socialist party withers away.

• The Communists never gain power in Russia.

Although the Russian army suffers a paralyzing defeat on the Eastern Front, it is mostly intact when the war ends and the troops march home. The German government is too busy saving itself in 1917 to send the exiled Lenin back into Russia. Without their charismatic leader, the Bolsheviks of Moscow make little progress stirring up revolution. Russian veterans happily round up the loudest revolutionaries and ship them off to Siberia. By November, when the Bolsheviks would have seized the government, they have disappeared underground.

• Europe forms a union.

Since the war ends almost two years earlier, Roosevelt is able to talk the Allies into seeking reasonable reparation costs from the Germans and their allies, the Austrians. Before he dies in office in 1918, he has convinced England, France, and Italy to a continental plan similar to that created for France after Napoleon’s defeat. Having exiled its Kaiser and become a Republic, Germany is invited to rejoin the European nations. For the next 30 years, the Congress of Paris ensures the status quo between nations and suppresses any talk of revolution or nationalism.

All these benefits wouldn’t have accrued without some problems. According to one way of looking at history, if Communism didn’t get a strong foothold in Russia, it would have done so in Germany. Japan would still have emerged as a world power and very likely would still have invaded China. If successful, Japan and the US would have very likely found themselves in conflict over control of the Pacific.

Very probably, the atom bomb would have still been developed. Given human nature, it’s very likely one country or another would have had the curiosity to use it. Which country that might have been is anyone’s guess …

See also “100 Years Ago—A Chaotic Presidential Election.”

Tribute to Our Troops Essay Contest Winners

Thank you to all who participated in The Saturday Evening Post’s Tribute to Our Troops essay contest.

“The Saturday Evening Post, for nearly 300 years, has been proud to showcase the American way, and through this contest we honor soldiers past and present who risk their lives every day for our country,” says Steven Slon, editorial director and associate publisher. “We are very excited to present the inspiring tributes from our readers.”

Each of the winners will receive a watch courtesy of our co-sponsor Speidel.

“Speidel is very proud to have been a part of The Saturday Evening Post Tribute to Our Troops essay contest, and we offer our heartfelt thanks and congratulations to each of the winners,” said Lynn-Marie Cerce, co-owner of Speidel. “We would also like to thank all of our loyal customers—many of them Saturday Evening Post readers—who help us provide critically-needed financial support and services to members of the military and their families through our Change A Band, Change A Life™ charitable giving program.”

As part of the program Speidel is donating a portion of all sales proceeds, including purchases made online at speidel.com to Operation Homefront.

The following essays are the top 20 entries selected by the Post editors:

Honor Thy Brother

By Elizabeth Heaney

Walking through the battalion offices, I see a big, broad-shouldered staff sergeant intently focused on a dark blue uniform lying on his desktop. As I watch from the doorway, he leans over and places a narrow silver pin on the uniform’s chest. Before attaching the pin, he checks its placement in all four directions with a measuring device that calculates tiny, perfect millimeters.

After securing the pin, he checks each brass button down the front of the uniform in those same precise millimeters.

He’s wearing delicately thin white gloves on his huge hands, and touches the uniform gently, reverently. I’d seen soldiers prepare their dress uniforms to go up for promotion; this was different.

“Looks nice—you up for promotion?” I say from the doorway.

“No, ma’am. I’m escorting Tompkins’ body back to Iowa.”

Silence stretches between us.

“I’m so sorry you have to do that.” Then I add, “And I’m very grateful you will.”

“I wouldn’t have it any other way, ma’am. He was my soldier.”

Always a Hero

By Anne Linja

Navy Master Chief David Charles Linja—my husband, my hero—was holding my hand as we headed towards his retirement ceremony. There were many emotions and thoughts going through my mind. The most prevalent was “He’s coming home to us, our family. The U.S. may have had his heart, soul, and body for 30 years—and thankfully he stayed safe throughout all those years—but now he’ll be husband, dad, brother, son.”

As we stepped into the elevator, a fellow squid said, “Good morning, Master Chief!”

I responded, “He’s retiring today. It’s his last day.”

The sailor looked at me and respectfully said, “No, ma’am. He’ll always be a master chief.”

My husband suddenly had the biggest grin on his face, full of pride, knowing that he spent the last 30 years doing exactly what he was supposed to do.

Job Well Done

By Kathy Manier

While growing up in Orange County, I was always taught to thank our military for their service but never really had a full grasp of why I was thanking them—except for the obvious reason, fighting for my freedom.

Within the last couple years, I’ve personally come to know many service members, and their stories are humbling to say the least. To them, they are not heroes nor see any need to be thanked. They go to work every day like the rest of us—to do their job as best as they know how—except they don’t always get to come home at the end of the day.

They leave their families for months on end, work through holidays, and take the weight of the world’s problems on their shoulders. They sacrifice their safety, getting shot at, but for them it’s just another day at the office.

So for all the tears before each deployment, the PTSD that becomes the norm, the loved ones that are lost, the weeks of training in the middle of nowhere with no shower or bed, and the endless sacrifices they make on a daily basis, I thank them for their service, for just doing what they consider their “job.”

In the Steps of Our Ancestors

By Debbi Nelson

As a female child born into a lineage of proud males, I was raised on stories of ancestors who fought and died in the great conflicts—dating back to the American Revolution—of these United States. Images of draft cards and photos and the family stories still hold places of honor in my mind. As a youth, I could recite the stories, but, as an adult, I can feel them.

These were gutsy, in-your-face characters that hid their fears and left their families to benefit something bigger than themselves. Some never returned to their mothers or children. Some carried the horrors of war with them for the rest of their lives. But all of them watched with real pride each time the wind was slapped back by the Stars and Stripes. Their lives, and the lives of their comrades, were gifts that will never be forgotten.

Today, in big cities and small towns across this country, the tradition continues. I see young men and women putting their lives on hold in order to put on uniforms. The transportation and technology are different, but the American soldier is still the same, unafraid to defend. May God bless their every step!

No Thank You Required

By Greg Woodburn

After enjoying a wonderful meal on vacation with our two then-young children, we waited for our check.

Ten minutes became 30.

And we finally left without paying, but let me explain: Two businessmen across the room paid our bill, but requested we not be told until after they left. They saw a happy family, the waiter now explained, and simply wanted to do something kind with no thank you required.

Fourteen years passed, and then, last summer when I was leaving a local steak house, a U.S. soldier dressed in camouflage walked in.

“Hi,” I said. ”I want to thank you for all you do.”

“I appreciate that very much, sir,” the authentic American hero humbly replied while shaking my hand.

I wanted to say more, something less trite, but the table for two was ready and the hostess led the strapping soldier and his happy mother away.

I hope they ordered appetizers, wine to celebrate his homecoming, prime rib, plus dessert. And afterwards, I hope they had to wait a good long while, enjoying each other’s company and some laughs—even as they grew a bit impatient wondering where in the world their waiter was with the check.

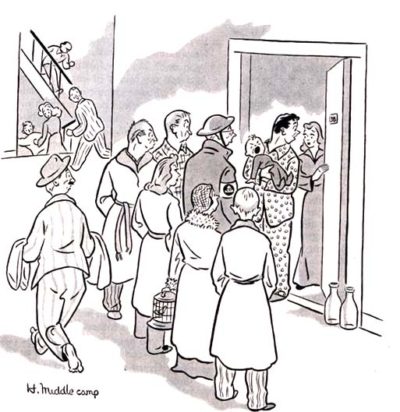

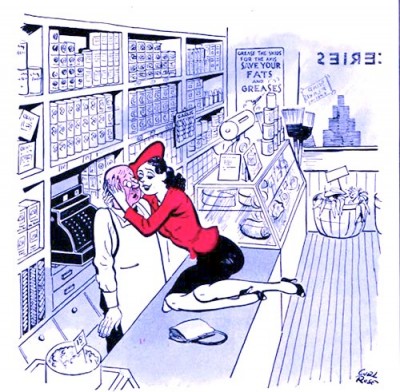

Cartoons: Women of World War II

"Now let's see your pass—this time

without the gestures."

"So, I says to the boss——"

"And when you go forth into the world,

be it as riveters, welders, or mechanics,

keep ever bright before you the slogan of

Sweet Lawn Seminary—'A lady, first, a lady always!'"

"It’s some game she learned in the Army."

"Well, frankly, if he's in the armed forces, you don't need anything at all!"

"Do you suppose my working on an assembly line had anything to do with it?"

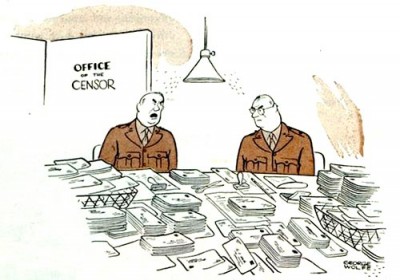

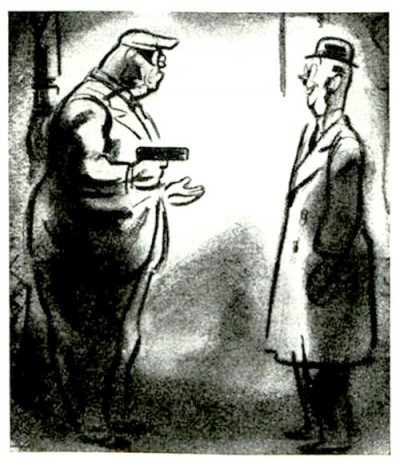

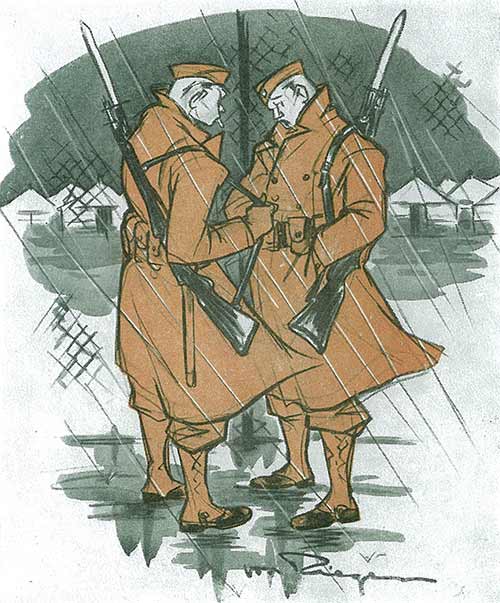

Cartoons: World War II

“By the time you are reading this,” wrote Post editors in an early 1944 issue, “American troops on various war fronts around the world will be reading the first monthly overseas edition of the Post.” The issues were lightweight, since ads were omitted, but they contained several articles, short stories, and many cartoons. The soldiers loved cartoons!

“Hardly any of them have trouble reading that chart."

“They say he sounds like the siren.”

“How would you like to be in that guy’s shoes? Facin’ DiMaggio, with the bases loaded!”

“It’s no use, Mrs. Tuttle, I just don’t have any butter.”

“Well, the way I figure it censor censor censor censor and censor censor censor censor!”

“Oh, come now. With all that’s happening these days you don’t think you could frighten me?”

Click here for another World War II cartoon gallery.

Outsourcing U.S. Military Might