Walter Winchell: He Snooped to Conquer

If he is remembered, the journalist and radio man Walter Winchell evokes a few different types of memories. Baby boomers might recall the narrator of the 1959 series The Untouchables. Their children might have caught the HBO biopic Winchell that starred Stanley Tucci as the fedora-donning gossip columnist. Younger people likely won’t recognize the name Walter Winchell at all. But consider this: every time you guiltily click on a link promising a juicy scoop on a washed-up actor, Winchell is somewhere, smiling.

In his heyday, Winchell commanded a collective audience of about 50 million Americans — two-thirds of the adult population in the 1930s. As biographer Neal Gabler claims in American Heritage magazine, anyone walking the streets on a warm Sunday evening in any city in America at the time would hear Winchell’s staccato voice through successive open windows on their way, giving updates on the war in Europe or a famous couple who might be “infanticipating.”

Making and breaking celebrities and politicians in his syndicated columns and radio broadcasts, Winchell built a complicated legacy. Though he often leveraged his platform to give a voice to everyday Americans, Winchell’s lifelong quest for popularity became his own undoing.

A new PBS American Masters documentary, Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, offers viewers a new look at how, for better or for worse, Winchell created “infotainment.” The documentary tracks the gadfly’s rise during the Great Depression and his slow decline in the McCarthy era, with Whoopi Goldberg as narrator and Stanley Tucci reprising his role as Winchell.

Director Ben Loeterman says that he was drawn to Winchell’s story as a sort of explanation of the current state of news media: “I think understanding the origins of how news is shaped and delivered and the importance of story, that has become absolutely part of journalism today, started in that sense, I think, with Walter Winchell.”

Winchell’s career arc can be simply understood with his own words: “From my childhood, I knew what I didn’t want: I didn’t want to be cold, I didn’t want to be hungry, homeless, or anonymous.”

In his early years reporting Broadway gossip at Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic (a tabloid commonly called the “Porno-Graphic”), Winchell learned that “the way to become famous fast is to throw a brick at someone who is famous.” He quickly made enemies, namely the Schuberts, who banned him from their theaters. Winchell secured a hefty readership, though, with his euphemistic claims about Jazz Age New Yorkers. Soon enough, he was rubbing elbows with Ernest Hemingway, Al Capone, and plenty of others who feared and respected his power of the press. He regularly attended Manhattan’s Stork Club, where anyone who was anyone knew to find him.

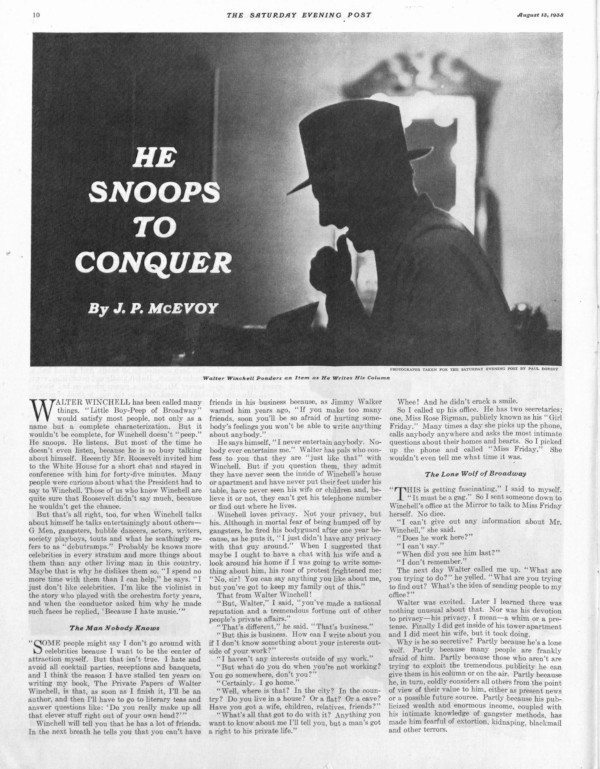

J.P. McEvoy turned a journalistic eye onto Winchell and his brand of “personal journalism,” writing the profile “He Snoops to Conquer” in this magazine in 1938. “Because he was fearless, talented, tireless and tormented by an unappeasable itch for success,” McEvoy wrote, “he arrived at his present peak — where he lives in a state of ingenuous surprise that he has arrived and a gnawing fear that he cannot remain.” Winchell was making about $300,000 a year at the time, between movies, radio, and his column at the Daily Mirror, which was syndicated to thousands of papers across the country. He had become famous for, among other things, coining provocative slang many called “New Yorkese.” H.L. Mencken, in The American Language, noted Winchell’s introduction of several words and phrases into the lexicon. Reno-vated (divorced), obnoxicated, Hard Times Square, intelligentleman. A young couple might be cupiding or “makin’ whoopee.”

Winchell’s reports weren’t limited to celebrity gossip, though. He was an early, outspoken critic of Nazism, taking shots at Hitler as a “homosexualist” called “Adele Hitler” (“he put a hand on a Hipler … ”) and regularly blasting antisemitic Nazi propaganda. When a German-American man named Fritz Kuhn began rallying Nazi sympathizers, first in the Friends of New Germany and later in the German-American Bund, Winchell found a nearer target for derision (“the SHAMerican”). Kuhn thought of himself as a sort of “American Führer,” organizing youth camps and rallies with the growing Bund in the ’30s. Right before more than 20,000 Nazis and Nazi sympathizers descended on Madison Square Garden in 1939 for George Washington’s birthday, Winchell tore into “the Ratzis … claiming G.W. to be the nation’s first Fritz Kuhn … There must be some mistake. Don’t they mean Benedict Arnold?” Winchell was delighted when Kuhn was sentenced to prison for embezzlement that year, writing about how the warden would be “the chief sufferer.”

At the start of President Roosevelt’s first term, Winchell praised the president as “the nation’s new hero,” sparking a close relationship with the administration that would prove fruitful for both of them. Years later, Post editor and former Roosevelt liaison Ernest Cuneo wrote all about how prominently Winchell had figured into their strategy to get FDR a third term (“Look, Walter,” I wanted to say, “you are the Third Term campaign.”).

Winchell was taken with President Roosevelt — and perfectly happy to act as a patriotic mouthpiece for the New Deal and American intervention in the war — but after Roosevelt left office, the gossip reporter found himself politically stranded. In 1951, Winchell affronted African-American performer Josephine Baker when he failed to defend her allegations of racism at his beloved Stork Club. Then, in 1954, he frustrated public health efforts by incorrectly announcing on his broadcast that a new polio immunization “may be a killer,” contributing to a dangerous anti-vaccination backlash. Winchell was really sunk, however, after he aligned himself closely with Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn.

“If he thought there was a star he could hitch himself to,” Loeterman says, “that was more important than the politics or any of the rest of it.”

Winchell transferred his disdain for Nazism into the anti-Communist witch hunts of the ’50s. He had vocalized his opposition to communism throughout his career, but McCarthy and Cohn made him an honorary member of a new — doomed — club. As Gabler put it, “he would lose because his populism had transmogrified into something cruel and unmanageable, just as his detractors had charged. Once a lovable rogue, Walter Winchell had become detestable.” He had brief stints on television in the ’50s, but nothing stuck. Winchell’s newspaper and radio routines were things of the past, and he had cultivated too much public distrust.

Although he faded from the public eye, Winchell’s mark was already made: the “welding” of news and entertainment. Two years after his death, People magazine was launched, and no shortage of commentators and gossips have haunted our screens and papers since. Kurt Andersen wrote in the Times about the evolution of Winchell’s personal journalism, “As star columnists leveraged their columns to accumulate personal celebrity and their personal celebrity to generate more readers, the market for their sort of journalism grew.”

If Winchell isn’t remembered, then he ought to be, if only so that we can more clearly understand that clickbait has a snappy, five-foot-seven predecessor who was one of the most famous men of his time.

Featured image taken by Paul Dorsey, The Saturday Evening Post, August 13, 1938

“Partisan” by Michael Shaara

A former boxer and policeman, Michael Shaara published his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Killer Angels, in 1974. Shaara had published many science fiction stories in publications like Galaxy Magazine, but his work in The Saturday Evening Post appears to be his first foray into historical fiction. His story “Partisan” follows an American soldier revisiting Yugoslavia years after the country was devastated by World War II.

Published on May 26, 1962

He crossed over the border at Trieste. He was driving a white Mercedes registered in Italy, but he was an American. He stood under a great white concrete star while they checked his passport — the sight of the thing, monolithic, slope-shouldered, not at all like American stars, made him slightly uneasy.

He had never been in a Communist country before. The customs officers were silent and unsmiling, but polite. They did not check his car or his luggage. He saw other tourists come up to the gate, three Germans in a Volkswagen. One got out and wanted to take pictures, but the guard shook his head and became suddenly quietly uncivil, and their car was searched. It was still standing there when the American drove off. No one wished him a pleasant stay in Yugoslavia.

He drove south to Rijeka. It was a new asphalt road, and he made good time. The country was rocky, hilly, very poor. He began to see extensive ruins, the first he had seen in Europe. All along the road there were roofless stone houses, sometimes alone in gray, barren fields, sometimes in clusters of three and four. The American knew something about this; he had fought here during the war. There had been bitter partisan action in these hills, and the Germans had fought back with reprisals. And of course the Germans were always thorough. No one came back after the war to rebuild, because there was no one left. When the Germans suspected a house of partisan activity, they came and shot everyone in it and then satchel-charged the house. They did that sometimes to whole villages. When the roofs blew off, the gray walls still stood, and the American passed them now one after another — dumb, murdered ruins with bushes growing inside. In the cool, gray stillness of the day he felt a gathering chill. He was beginning to remember.

His name was Lawrence Bell. In that summer of 1960 he was forty years old. At the beginning of the war he had been twenty-one. He went into the first-formed paratroop division, served with some distinction, went on from there into the Rangers and finally was transferred to the OSS.

He had parachuted into Yugoslavia early in 1944 with a small knowledge of Croatian and some arms and explosives. He was there to teach partisan bands everything he knew about demolition. He stayed on through the summer and fought often with a small group based in the bare rock mountains above Godice, a few miles in from the Adriatic, near the great resort area of Split.

It had been a very bad time. The people in the villages had been caught between the two fires, the partisans and the Germans. Toward the end he had begun to feel that he was killing more Yugoslavs than Germans. But the group he fought with was very good, under the leadership of an intense, honest, murderous old man named Lalic, who resented him at first, not because he was young, but because he was a foreigner, yet who approved of him enough in the end to give wordless sanction when an affair developed between Bell and one of the Lalic women.

Not a woman, really; she was only a girl, only seventeen. It was a long time ago, so long he could not remember her face, but only the size of her — firm, tall, so very young. He remembered not the things they said, but the yellow light of the afternoon, the fear he felt of the coming dark while he held to her on the grass behind gray rocks. All he could really remember was one warm afternoon alone with her in the mountains. They walked hand in hand and ate blackberries until her lips were blue, and he remembered kissing the blue lips. Her name was Melitta. He remembered that he had called her “Mel,” and it made her laugh, but he still could not see her face.

He had never been in love with her. He needed her desperately at the time, but he knew even then that he was not in love with her, not a Slav peasant, not him. He did not believe either that she really loved him. She was too young to know about love. He was beginning to be very fond of her, and then one night he was wounded in a raid on the naval base at Ploce. He was hit in the legs and stomach and he knew enough about wounds to know that he would probably die.

They got him back a little way into the mountains, and the old man, Lalic, used the radio and called for help. It was a risky thing; the Germans were all around and getting closer, but Lalic and the men carried him down through the night, and a seaplane came in on the Adriatic and picked him up. He did not remember much of that night — he was in considerable pain — but as the plane took off, he was sure he heard shooting. He never remembered saying goodbye to Melitta.

He was taken back to Africa, and the medical people pulled him through. He was in a hospital all that winter and he heard nothing of the group at Godice. He was told by headquarters that radio contact with Lalic had been lost. For a long time he hoped that Lalic had lost only the radio, and, it occurred to him finally with a shock that he was very fond of that brutal old man. He would lie awake in the night thinking of them all back there in the hills, thinking of Melitta.

But the Army nurses were very nice and very pretty, and he was a long time in hospitals and he thought less of them all when he was sent back to the States. He did try to find them when the war ended. He wrote several letters to the old village, Godice, to all the names he could think of. But then the country went Communist, and he never got an answer.

The years went by; he met a wealthy girl from New Jersey; he got married. He was not a man to talk about what had happened in the war and he never told his wife about Melitta. After a few years he no longer thought about her, although he sometimes wondered, whenever Yugoslavia was in the news, if any of the old group had survived. They had been good men. When he had been with them, he had been a pretty good man himself. He stayed married for ten years. He had one child, a son, to whom he was very close. His wife divorced him in 1958. He never clearly understood why that happened; but after ten years, there was nothing left to live with, and he was not even sure if anyone was really to blame. She left him, she said, “while there was still time.” He did not mind her loss so much as the loss of his son. There was no time now for another son, another family. He had mellowed a great deal over the years; he had become gentler and more thoughtful. There seemed to him to be something strongly indecent about having more children, by another woman. He did not know why. But he knew it was all done — he would not marry again. He had nothing much to do then but his work, which was now no longer important. When he came to his fortieth birthday, he had become a silent man, no longer an optimist.

In the summer of 1960 he suddenly took a long vacation. He went to Europe and then on to Yugoslavia, moving instinctively, not so much out of curiosity as because he really had nowhere else to go. Coming down through the windy rock, past the roofless houses, he felt for the first time in years the old emotion slowly stir. He wondered if any of them were alive. He wondered if she was still alive.

He stopped for the night in Zadar. For the first time he was truly aware that he was in a Communist country. The town was bleak, grim, without store fronts, cluttered with rubble. The few cars he saw on the streets belonged to German tourists; he began to see that German tourists were everywhere. There was a grave irony in that — the wealthy Germans strolling once more among the rocky ruins.

Dark people, poorly dressed, stared silently at him as he passed. Children waved, grinning. He guessed that only important people drove cars in this country — commissars and the like, or tourists. He saw several policemen, large clean men in white shirts and blue trousers. He saw them always alone, standing withdrawn and cold, with a hard, watchful indifference. He was to realize later that the entire time that he was in Yugoslavia he never saw anyone speak to a policeman.

In the hotel the desk clerk spoke to him first in German, but when he pulled out the American passport, the man’s face cracked into a startlingly unexpected grin. The clerk, short, thick, heavily mustached, was obviously delighted to see an American. He pumped Bell’s hand and led him personally to his room, helping him carry his luggage. They went down a long dark hall beautifully laid out in smooth stone and marble, lighted in the latest, softest, most indirect fashion. There was a deep red carpet on the floor, but it was surprisingly dirty. There was all over the hotel a confusing mixture of opulence and neglect — a beautifully designed patio, filthy tablecloths. potted plants in great urns, dying. The clerk shook his hand energetically when leaving; Bell sensed no need for a tip. “Dobar America,” the clerk said happily, and it was a moment before Bell remembered the word: “Dobar” — “good.” Good America. At this bit of unexpected warmth he suddenly felt very good. There had certainly been little warmth at the border. But when he lay awake that night, he did not think about it. He was remembering Melitta.

The next morning when he came down to leave, there was a small crowd gathered around his car, old people and many children and several men from the hotel. They were all smiling: an old man came up and took his hand. “You American, you stay long here Yugoslavia. Too many Germans. You stay, swim, have good time. I live San Francisco,” he prodded himself joyfully, “long year, many time.” Bell thanked him. He shook hands all around, trying to remember some Croatian, but all he could remember was “falla,” “thank you.” He left feeling very good. It was a rare thing to be liked just because you were an American. He could not understand it. He knew that they were a loyal people, a stubborn people, and he guessed that was it — the war; they were still fond of their allies. And then, he thought, considering the many armies that have come this way, I guess we’re the only people they know of that never did them any harm.

He went out of Zadar and down the lovely Dalmatian coast. That was another thing he had long forgotten — how beautiful it was. The road was pretty bad, but on his right the Adriatic gleamed a magnificent blue-green, and great rock islands lay long and gray across the sea. When he came down close to the water, he could see people wading, swimming — and he remembered with an abrupt, explosive shock one day with Melitta down in the sea, a day in August toward the end, very bright, very hot, and Melitta standing to her waist in the cool fragrant water and gazing up at him with a shattering look of devotion, hands on hips, her long hair washed sleekly down over the bare brown shoulders, the wide, the lovely smile, and he could see it all so clearly he felt a physical thrust into his stomach.

The vision vanished. He was alone again on the long, dusty road. He looked up from the sea toward the gray mountains inland, saw clouds clustered as if snagged on the sharp rock peaks. He began to feel a deep edge of excitement.

He made Split that evening. He drove past the great stone columns of the Palace of Diocletian, went by just at sunset, saw the ragged children of the People’s Republic playing in the rubble below the vast Roman stones.

This was beginning to be his country; from here on in he would recognize the land. But here also the coast was crowded with tourists, still mostly German, thronging the streets so thickly he had trouble driving through. He checked into another hotel, and it was the same as the first, beautifully designed, badly neglected, and the clerk again was delighted to see an American. He spoke fairly good English, welcomed Bell to the hotel. There were three men lounging sleepily behind the desk. They all waked at the same time and smiled at him. He felt a broad grin break over his own face. He could not get over how pleased they were to see an American.

He went down that evening to sit in the restaurant out near the sea. Tourists still moved down the wide street, empty of cars. Many of them were Yugoslav, strong brown people, many quite tall, most of them poorly dressed. He noticed that many of the men were unshaven, but the girls were invariably neat and clean. He was lightly surprised to look down the street and see a bright neon sign — Hotel Bellevue.

Late in the evening the crowd had begun to thin, the tables near him were empty. He sat drinking small glasses of slivovitz — Yugoslav plum brandy — and listening to the quiet sea. A tall, thin waiter in a shabby white jacket came over and regarded him fondly.

“You first time Yugoslavia?”

“No. I was here in the war.”

“The war. You here?”

“Yes. At Godice.”

“Godice?” The man stared at him. “You at Godice. Partisan?”

Bell nodded.

“But — you young man.”

“Yes,” Bell said. The man went on staring at him with gathering awe. Then he excused himself suddenly and dashed off and got another waiter and talked excitedly to him for a moment, and they both came back grinning. Bell asked them to sit down. They shook hands all around, and Bell caught the thin one’s name; it was Evo. They sat across from him, staring at him with delight.

They chattered for a moment in sputtering English, and then Evo dashed off again. “We drink to partisan!” he shouted and returned with more slivovitz and a short stubby man from the hotel desk. Bell began to feel very good. The stubby man sat down and asked with somber authority about the partisans, and Bell told him briefly. Bell asked if they’d ever heard of the Lalic group.

“No,” the stubby man said and shook his head apologetically. “Is not possible. We work in hotel, you see? And go to state school. We learn little English, French, German. Sometime learn Russian.” He chuckled. “But no more.” Everyone grinned. Evo poured more slivovitz. “But is no man here from Godice. I from Zagreb. Where you from?”

“Florida.”

That meant nothing. He mentioned Miami. There were slow dawns of awed recognition. “Florida? Meeahmee? Many millionaires!” They knew about Miami from American movies. From then on they regarded him as an immensely wealthy man, but it seemed to make no difference. It was not until much later that he realized how truly wealthy, in comparison to them, he was. Most of what they knew about America had come from the movies. They kidded him about the movies, the cowboys, the gangsters, but it was not all light fun.

“America very beautiful,” Evo said suddenly. A quiet came over the group. “America.” A deeply wistful look came over the gaunt face. He paused, held out his hands gravely. “America,” he said again softly. He shook his head. Bell was moved. The stubby man grunted.

“Your country has much luck,” the stubby man said. “Here” — he gestured toward the mountains and grimaced — “here is very poor. Too many wars. The people — but we build. We be better soon.” He said this almost defiantly, looking not at Bell but at the two waiters. They sat staring into the table.

“I like the mountains,” Bell said. “We have no mountains in Florida.”

“You grow no food in mountains,” the stubby man said gloomily. “In rock you grow nothing. Here is nothing.” He leaned suddenly, earnestly across the table. “I want explain you. No Communist your country. But you understand, please. Here is nothing. Is no electric, no power, no roads, no factories. If no electric, then is no cold, no — icebox. Food not keep, is no good, spoil. Is no machines like in your country. Is much rock. People all poor. How we get roads if state not do it? How we get electric if state not do it? No money here, Yugoslavia. We must build new, but no money. So must take from people, from Yugoslavs, or must ask from America. Everything — very hard. With no roads, can ship nothing. With no electric, no can raise many chickens, milk many cows. But is cost money; and America help, and that is very good. You understand?”

He was in deadly earnest. He wanted desperately for Bell to understand.

“For Yugoslav this only way — Communist. Not for you; you no need. King no good, no want schools for people, want keep them down. But government help now, you see? But no war. Too many wars. Someday we have all — factories, electric, food. People eat, be happy. Then no more war. Why be war if people eat? You see? We do this.”

Bell nodded. The two waiters sat silently, still staring at the table. After a moment, the stubby man excused himself, saying he had to get back to the desk. Bell poured more slivovitz. The two waiters brightened.

Evo raised a glass. “Hai hai uzhivai!” he cried suddenly. “Toast!” Bell repeated it after him, grinning. They drank. Evo fixed Bell with a fond, approving smile, then gestured with distaste at people sitting at other tables, who had looked over at him when he called the toast.

“Germans,” he said. “Too many Germans.” He spat. “I fight. I no forget.” He leaned forward, grinning. “But we take their money.” He chuckled. “For Germans Yugoslavia is cheap; so we let them come and we take their money. Everywhere for Germans prices go up.” He chortled, then grew suddenly grave. “You make sure, you, where you go, they know you not German.”

Bell said he would. Evo suggested he get an American flag and put it on his car. They considered this and drank. Evo glanced around, saw the stubby man nowhere about, leaned forward again.

“In America,” he asked, “all waiters have cars?”

Surprised, Bell nodded.

“All waiters?”

“Most,” Bell said. He explained about waiters’ salaries, and it came to him suddenly that in this country Evo was really an important waiter. He served in one of the largest hotels in one of the most important tourist areas in the country. His equivalent would be a topflight waiter in New York or Miami. In America, Evo would be making very good money, and Bell tried to explain this diplomatically and also to explain unions, which interested both waiters profoundly.

After a moment, Evo smiled. He explained his salary to Bell. It amounted to about eight hundred dollars a year. He said it would take him twenty years to save enough money for a car, any car. He said he had a wife and two children. He picked up the bottle. “Hai hai uzhivai,” he said, and they had another round.

They sat silently for a while, and then Evo roused himself. He looked round again cautiously, then said, “You know one thing? Is Communist now here” — he struggled for the words — “is Communist from here, Yugoslavia, all the way there, all the way — ” He motioned east. “From here to Pacific Ocean,” he said quietly, “is Communist.”

It was a chilling thing. Bell nodded.

Evo grinned faintly. “All those people … very hungry. If you fight Russians … all gone. Everything die. But” — he paused and smiled grimly — “if you fight Russians, make long war. Make four, five year. You eat, yes, but they no eat. They have no … system. They starve, have other revolution. Here we say win war with food, not guns.”

He regarded Bell thoughtfully, hopefully. “They not ahead of you, Russians? They not really ahead?”

Bell shook his head. “I don’t know. I don’t think so. I hope not.”

“I no think so either.” Evo smiled. “You have engineers, but all work television.” He grinned widely. “Russians … I have one friend once, from Osterreich, Austria … come here after war. Was Communist in Austria, all in war Communists. Love Russians. Love Russian like woman. Then war end, and Russians come his little town. Rape all women, all little girls, old women, rape everybody. Rape his family. He come here then.” Evo grinned. “Russians — ” He looked up and saw the stubby man coming. He was silent.

The stubby man sat down and went off again explaining Communism. He did this by right, as if anything they were talking about before he came was without consequence. Bell sat politely, but he was beginning to understand. He had a stark sense of tragedy. These starved and grave and battered people had been overrun with enemies for centuries.

At the next table there were suddenly two very pretty, well-dressed blondes. They sat looking around for a waiter, but neither man at Bell’s table moved. The blondes became annoyed. Bell was uncomfortable but said nothing. Eventually Evo rose, yawning, and started toward the table. He winked at Bell.

“Germans,” he said and shrugged. The stubby man excused himself again and left. The last waiter sighed and drained one more glass of slivovitz. He looked up at Bell, holding the glass, and smiled.

“The brewery changes,” he said softly, “but the wine remains the same.”

He left. While Evo was gone, one of the blondes looked over at Bell and smiled.

“You are American?” she said. She had a really lovely smile. He was surprised to have her pick him for an American so quickly. “Isn’t the service here terrible?” she said.

Bell shook his head. “I — they’ve been very nice to me.”

“These people,” the girl said and shrugged. “Would you care to join us?” She smiled again. Her English was very good, with strong traces of British. He did not want to join her, but he could not politely refuse. He sat at their table. Evo came back and stood watching him, a knowing grin on his face. Bell felt at first that he had in some way betrayed him, but Evo winked broadly, and Bell realized that he was wishing him well. Anyway, there was no doubt about the attitude of the one girl. She was bored, and he looked as if he might be interesting. Her name was Ursula. She went on talking about the terrible service she and her friend had seen all over Yugoslavia.

Bell replied that he hadn’t found it bad, but then he was an American, and perhaps the Yugoslavs had no fondness for Germans. He didn’t know why he said that, but he said it. The girl was astonished, did not understand him. He blinked, wondered what she could possibly have thought of all the ruins along the road. He explained that, of course, the war — but she was annoyed, quite annoyed. She said, “That is foolish, really. There is no reason for people to dwell on the war. That is all done. That is no good for world peace.”

Bell shrugged.

“And of course,” the girl said quietly, “we have our ruins too.”

That you do, Bell thought, that you do. He was confused, he did not want to talk about it. He was also very tired. He excused himself; she gave him another very warm smile.

“You will be here tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow evening, yes.”

“We will see you then? Perhaps you will go with us to the Palace of Diocletian.”

Of course, Bell said. The girl smiled with promise. Bell left, passed Evo standing by a stone column.

“You get the German girl,” Evo chuckled. Then he said, “You go tomorrow to Godice?”

“Yes.”

“You come back, yes? We talk about America.”

“Yes,” Bell said.

In the morning he passed through a cleft in which the partisans had once ambushed a German convoy. He stopped and looked and smelled the silent air. There were no traces. The day came back vividly; layers of his memory peeled away. There it was — blood pools in the gray rock, bodies, brains, flecks of red flesh stuck to bright, hot metal, cartridge cases gleaming in the sun. He remembered an old man dying, a gray-haired partisan, such a little man — what was his name? Crying. And then a young German, very young, and the look on his face when Lalic came up and pointed the gun down to finish him. Usually he was not this good at memory; he could remember feelings better than sights, he could remember the sense of loss, the smell of fear. Sometimes he thought that was a bad thing, to remember the feeling and not the face, to remember the smell of his lost wife and not what they had done together.

But here he could remember everything. Veils were falling. He felt increasingly alive. He remembered that same night after the fight, back in the hills with Melitta, how hungry he was.

Up above that site was a small village. It was empty; all the roofs were gone. Along the roadside he passed a white concrete monument bearing the names of the dead — KILLED BY THE FASCIST TERROR. On top of the monument was a white star. The Communists were very good at that, at monuments to the dead.

He drove on, feeling oddly cold. He could remember some of the names now — Ivan Maras, Marko Seveli. Some of them must still be alive. And Melitta. It began to be as if no time had passed at all. It was as if he were going back to them, and they were waiting, and there might still be Germans around the next bend.

He passed through small towns, and strong faces turned to stare at him. Children waved. He looked at the girls especially as he passed, and there were many to remind him of her — the long sturdy legs, the square, proud, lovely faces. He remembered what the Germans had done to the girls in some of these towns. He thought of Evo. What had happened to Evo’s women?

But the land was so poor. It was worse even than he had remembered. They had nothing, not even soil. There were no green fields, only small square plots every few miles, tiny hoards of topsoil painfully scraped together, bounded with rock walls to keep the wind and rain from carrying it away. Here grew straggly plants he did not recognize. There were a few places where the government had planted trees, tiny pines, in hope of bringing back the soil, of holding on to what was left. But to recover this area would take forty years.

He thought again, how many armies have passed this way. The Romans, the Germans. In the history of every family, killing, rape. We knew damned little rape in America, thank God, he thought. The grave faces watched him. He wished they could know he was an American. At last he came into Godice.

He turned off the main road, began climbing the mountain. Children watched him go by. A small boy ran alongside screaming, “Bonbon! Bonbon!” He went up the road with his mind a blank, looking for the house, Lalic’s house. It was alone just over the first rise, out of sight of the small town. He knew everything here now clearly, each small rise, each cleft in the rocks. But there had been more trees, many more trees. He followed the road until it gave out. That’s all right, he thought, it was only a path anyway. And he’d be an old man now, very old, seventy anyway. But there should be a path.

There was no path. There were bare rock and thornbushes. It was very hot, very dry. He left the car and began the walk up through the brush. He still did not think; he had an unreasoning hope. He made it over the top of the rise and looked down on the house.

There was no roof. The windows stared back at him like the eyes of a skull. All around him was still. A slight breeze came up from the sea. He took a deep breath and walked down to the house.

There was nothing inside, no trace of pan or bone. A thornbush grew where the stove had been, a pile of crushed stone littered half the dirt floor. He stared across the one big room, the room of the table and wine bottles and long talks in the night; the room of her hand held tightly when no one could see. He could not see them all anymore; they were all gone from his memory; there was no vision left, but only the feeling, only the loss. He looked out through the windows down to the bright green sea. He felt the soft wind, heard the deep silence.

Afterward he went up to the hill above and found the blackberry bush. It was August, the berries had fallen. He sat and looked down to the sea.

He stayed up there most of the afternoon. He had not realized it would hit him this hard; he had an ungovernable feeling of despair. The Yugoslavs — they had fought all that time and the ones that survived had nothing. They had got rid of the king and then the Germans and now they had the Communists. And beyond him to the Pacific — he looked off to the east and remembered Evo’s words — from here to the Pacific, the Communists. He had a terrible feeling of disaster. Where does it end, all the hate? Centuries pass, and it never ends. And they all died, and what does it matter? But what did they accomplish? What does it mean?

He went down to Godice. He thought of the German girl waiting in Split, the bright smile, and he felt nothing. We have our ruins too. Ruins all over the world.

When he came out onto the road, there was a crowd waiting. He got into the car, staring at the faces, the stony faces, but he did not recognize anyone. He was very tired. He tried to smile and pointed to himself and said, “American,” and people began to smile. Then a small, bearded man pushed up through the crowd and stared at him, wild-eyed. The man came closer. The man remembered him.

The man reached out and clutched his hand and said his name. He did not remember the man, but he held the hand and listened while the little man swung to the crowd and told them who he was, and, My gosh, Bell thought, he’s crying!

He was. Bell felt a tremor in his own throat. He got out of the car and began to shake hands. He was walked over to the shade of the trees, and someone brought him a cold beer. From the looks on all their faces he realized suddenly that in this town he had been remembered; here he would be a hero. One man could speak a little English, he was the owner of a small bar and he insisted on explaining to Bell over and over again that his place was “privat,” was not run by the government. They went down together to the bar, in the center of the town, the crowd growing every minute, the little man still sobbing and holding his hand. Bell asked for Lalic and asked what had happened. The little man tugged him wordlessly along to another white monument.

Bell saw all the names. Eight of the Lalics — dead of the fascist terror. In the sudden quiet he bowed his head.

When he looked again, he realized that the name of Melitta was not on the stone. He asked for her — Melitta Lalic.

The little man understood and brightened and waved down the road. The tavern owner smiled and turned him around. “She come. She come now soon, please. She know you here. OK?” Then he smiled and pointed.

Bell looked down the dirt street, straight into the afternoon sun. After a moment he made her out, the woman’s figure with the bright blaze behind it coming toward him in the dust.

“Larry?” the voice said. She stopped. He looked into her face, had to shield his eyes from the sun. She ran to him suddenly and put her arms around him, and he held her very close while all around him the crowd began laughing and cheering.

He stepped back and looked at her, holding both her hands. “Hello,” he said. He just looked at her — the same strong lovely face, the matchless smile, tears in the gentle eyes, small gleams of silver in the temples, an old faded dress, very clean, heavier, warmer, a stranger but not a stranger, something he had missed, something he had lost.

“How are you?” he said.

She nodded, tried to flick the tears from her face. “I cannot think of the English.”

“I am very happy to see you,” Bell said.

She came in to him again and held him. “I never think you come back,” she said. The crowd surged around him and began to push them back to the shade of the trees. He walked with his arm around her, feeling shaken all the way down in him, looking down at the few gray hairs, and she looked up at his face.

“I learned some English in school,” she said. “I hope if you come back.”

“I wrote to you,” Bell said. “I wrote to Lalic. Nobody ever answered.”

“No,” she said. “No letters.” She held him suddenly very tightly, and they sat on a wooden bench under the trees. There were now many bottles of beer, and a young boy came out with an accordion and began to play wild, rolling Slavic songs. Bell sat looking into her face. She had been seventeen then; she was nearly twice that now. She was beautiful.

“Thank God they never got you,” he said. She looked back at him, searching his eyes. “I went up to Lalic’s,” he said. “I thought … everyone was dead. But thank God they never got you.”

She went on looking at him. She bit her lip suddenly and looked away. He didn’t understand. Now beer was being pressed into his hands; he had to begin drinking toasts. At that moment a small boy, very blond, dusty, barefoot, pushed through the crowd and clutched worriedly at her legs. She smiled at Bell and leaned down and folded the boy in. She told him who Bell was, and the boy stared back in open awe.

“My son,” she said proudly. She put her arm around the tiny shoulders. Bell reached out and shook the child’s hand.

“I have a son too,” Bell said.

She smiled. She pressed his hand. She had again begun to cry. She looked up at him once more and she said, “I would have waited, Larry. But you never ask.”

“I know,” Bell said. “I never asked.”

He sat silently with the beer in his hand. After a moment he said, “Well, thank God anyway; thank God you’re all right.”

Her face was turned away from him. But he saw the corner of her eyes and the look there, the sudden spasm, silent and unseeing. She twisted around again to look at him, and the eyes were still unseeing, dim, but the mouth somehow smiled, there was in her now a strange mute softness — and he understood.

Of course he understood. She had not got away. He stared down at her with growing shock. They hadn’t killed her; much too pretty. She had finished the war in a German brothel.

He put a hand to his face and looked down into the dirt. He was aware finally of the little boy’s curious face, bent down in front of him, staring up into his eyes. He had to smile and reach out and touch the boy’s cheek. He looked up again at Melitta. He took another long drink from the bottle of beer.

She knew he understood. He knew she would never mention it. She sat holding his hand warmly, smiling down at her son, once again gentle and patient, once more warm and serene.

They sat together under the trees. The sun had begun to set behind a gray island. She told him of her husband, a good man, a farmer. She said she was very happy. She hoped that one day soon there would be electricity in her home and her boy would read more. He asked her if there was anything he might send her from America. She said no. Then she said, “Just a letter sometimes, for me, for my son.” But he knew he would send her many things.

He sat in the midst of the gathering darkness, the music. They all began to sing; she sang with the rest. She threw back her head and sang with warmth and great sweetness, still holding his hand. He knew now what he had missed. But he knew also that it was still there, still alive in the world, and he could find it again, even if he had to look a long time. He listened, he watched, he breathed deep and felt whole. He gazed around him at the people of the cruel earth, the people who had known so much — war and rape and Communists and kings. He sang with them all that night.

Featured image: Illustrated by John Falter / SEPS.

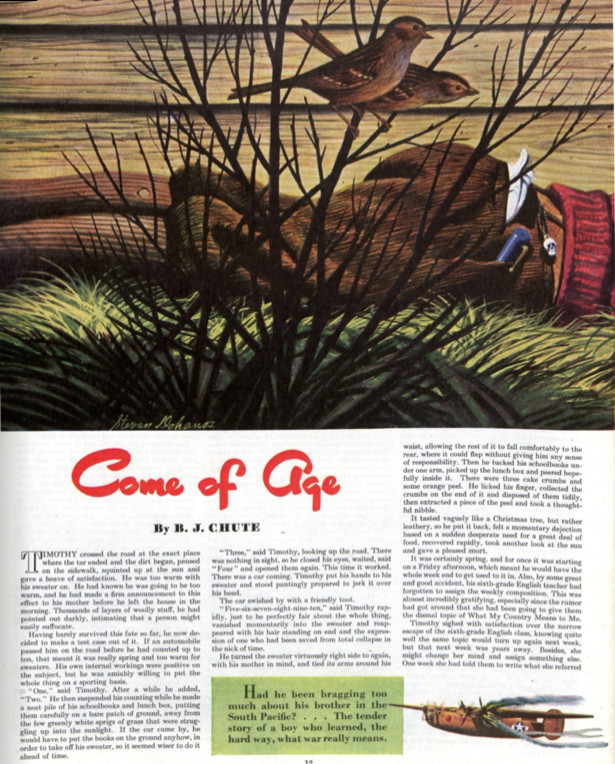

“Come of Age” by B.J. Chute

Writing young adult fiction in Boy’s Life, Child Life, and Boy Scout Magazine, B.J. Chute’s work ranges from fantastical romance to silly farce. In 1944’s “Come of Age,” her short story about a young boy coping with the unimaginable, Chute depicts the innocence of World War II-era America alongside devastating grief in the eyes of a child. As a product of its time, the story gives a snapshot of idyllic family life interrupted by the horror of war.

Published on September 30, 1944

Content Warning: A racial slur

Timothy crossed the road at the exact place where the tar ended and the dirt began, paused on the sidewalk, squinted up at the sun and gave a heave of satisfaction. He was too warm with his sweater on. He had known he was going to be too warm, and he had made a firm announcement to this effect to his mother before he left the house in the morning. Thousands of layers of woolly stuff, he had pointed out darkly, intimating that a person might easily suffocate.

Having barely survived this fate so far, he now decided to make a test case out of it. If an automobile passed him on the road before he had counted up to ten, that meant it was really spring and too warm for sweaters. His own internal workings were positive on the subject, but he was amiably willing to put the whole thing on a sporting basis.

“One,” said Timothy. After a while he added, “Two.” He then suspended his counting while he made a neat pile of his schoolbooks and lunch box, putting them carefully on a bare patch of ground, away from the few greenly white sprigs of grass that were struggling up into the sunlight. If the car came by, he would have to put the books on the ground anyhow, in order to take off his sweater, so it seemed wiser to do it ahead of time.

“Three,” said Timothy, looking up the road. There was nothing in sight, so he closed his eyes, waited, said “Four” and opened them again. This time it worked. There was a car coming. Timothy put his hands to his sweater and stood pantingly prepared to jerk it over his head.

The car swished by with a friendly toot.

“Five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten,” said Timothy rapidly, just to be perfectly fair about the whole thing, vanished momentarily into the sweater and reappeared with his hair standing on end and the expression of one who had been saved from total collapse in the nick of time.

He turned the sweater virtuously right side to again, with his mother in mind, and tied its arms around his waist, allowing the rest of it to fall comfortably to the rear, where it could flap without giving him any sense of responsibility. Then he tucked his schoolbooks under one arm, picked up the lunchbox and peered hopefully inside it. There were three cake crumbs and some orange peel. He licked his finger, collected the crumbs on the end of it and disposed of them tidily, then extracted a piece of the peel and took a thoughtful nibble.

It tasted vaguely like a Christmas tree, but rather leathery, so he put it back, felt a momentary dejection based on a sudden desperate need for a great deal of food, recovered rapidly, took another look at the sun and gave a pleased snort.

It was certainly spring, and for once it was starting on a Friday afternoon, which meant he would have the whole weekend to get used to it in. Also, by some great and good accident, his sixth-grade English teacher had forgotten to assign the weekly composition. This was almost incredibly gratifying, especially since the rumor had got around that she had been going to give them the dismal topic of What My Country Means to Me.

Timothy sighed with satisfaction over the narrow escape of the sixth-grade English class, knowing quite well the same topic would turn up again next week, but that next week was years away. Besides, she might change her mind and assign something else. One week she had told them to write what she referred to as a word portrait, called A Member of My Family. Timothy had enjoyed that richly. He had written, inevitably, about his brother Bricky, and it was the longest composition he had ever achieved in his life. He felt a great pity for his classmates, who didn’t have Bricky to write about, since Bricky was not only the most remarkable person in the world but he was at that moment engaged in being a hero in the South Pacific. He was a pilot with silver wings and a bomber, and Timothy basked luxuriously in the warmth of his glory.

“Yoicks,” said Timothy, addressing the spring and life in general. “Yoicks” was Bricky’s favorite expression.

“Yoicks,” he said again.

He was, at the moment, five blocks from home. The first block he used up in not stepping on the cracks in the sidewalk, which was not the mindless process it appeared to be. He was actually conducting an elaborate reconnaissance program, and the cracks were vital supply lines. By the second block, however, his attitude on supplies had taken a more personal turn, and he spent the distance reflecting that this was the day his mother baked cookies. His imagination carried him willingly up the back steps, through the unlatched screen door and to the cooky jar, but there it gave up for lack of specific information on the type of cookies involved.

Besides, he was now at the third block, and the third block was important, consisting largely of a vacant lot with a run-down little shack lurching sideways in a corner of it. The old brown grass of last autumn and the matted tangle of vines and weeds were showing a faint stirring of greenness like a pale web.

At the edge of the lot, Timothy paused and his whole manner changed. He became alert and his eyes narrowed, shifting from left to right. He was listening intently. The only sound was the peevish chirp of a sparrow; but Timothy was a world away from it. What he was listening for was the warning roar of revved-up motors.

In a moment now, from behind that shack, from beyond those tangled vines, Japanese planes would swarm upward viciously, in squadron attack.

Timothy put down the books and the lunch box, then he stepped back, holding himself steady. His hand moved, fingers curved knowingly, to control and throttle, and from his parted lips there suddenly burst a chattering roar.

The Liberator surged forward gallantly to meet the attackers. Timothy’s face became tense, and he interrupted the engine’s explosive revolutions for a moment to warn himself grimly, “This is it. Watch yourselves, men.” He then nodded soberly. It was a grave responsibility for the pilot, knowing the crew trusted him to see them through.

The pilot, of course, was Bricky. It was Bricky who was holding the plane steady on its course, nerving himself for the final instant of action. The deadly swarm of Zeros swept forward, but the pilot’s face remained impassive.

Z-z-z-zoom, they spread across the sky, their evil advance punctuated by the hail of machine-gun fire. The Liberator climbed, settling back on her tail in instant response to the pilot’s sure hand. As she scaled the clouds, the bright silver of her name, painted along the side, shone defiantly — The Hornet. Bricky had at one time piloted a plane called The Hornet. It was the best name that Timothy knew.

After that, it was short and sharp. A Jap fighter detached itself from the humming swarm. The Hornet rolled and the tail gunner squeezed the triggers. The plane exploded in midair, disintegrated and streamered to earth in flaming wreckage.

“Right on the nose,” said the gunner with satisfaction.

The Hornet had their range now. Zero after Zero fluttered helplessly down out of the sky, dissolving into the earth. The others turned and skittered for their home base, terrified before the invincibility of American man and machine.

A faint smile flickered across the face of The Hornet’s pilot, and he permitted himself a nod of satisfaction. “Good show,” he said.

Timothy sat down on the ground and drew a deep breath. Then he said “Gosh!” and scrambled back to his feet. At home, even now, there might be a letter waiting from Bricky, full of breathless and wonderful details that could be relayed to the fellows at school. A few of them, of course, had brothers of their own in the Air Force, but none of them had Bricky, and that made all the difference. He was quite sorry for them, but most willing to share and to expound.

Gosh, he missed Bricky, but, gosh, it was worth it.

A dream crept across his mind. Maybe the war would last for years. Maybe some one of these days, a new pilot would stand before his commanding officer somewhere in Pacific territory and make a firm salute. “Lieutenant Baker reporting for duty, sir.”

His commanding officer would look up quickly from his notes. “Timothy!” Bricky would say, holding it all back. They would shake hands.

For the entire next block toward home, Timothy shook hands with his brother, but on the last block spring got into his heels and he raced the distance like a lunatic, yelling his jubilee. The porch steps he took in two leaps, crashed happily into the front hall and smacked his books and his lunchbox down on the hall table. He then opened his mouth to shout for his mother, not because he wanted her for anything specific, but because he simply needed to know her exact location.

His mouth, opened to “Hey, mom!” closed suddenly in surprise. His father’s hat was lying on the hall table. There was nothing to prepare him for his father’s hat on the hall table at three-thirty in the afternoon. His father’s hat kept regular hours. An unaccountable sense of formality descended on Timothy. He looked anxiously into the hall mirror and made a gesture toward flattening the top lock of his hair. It sprang up again under his hand, and he compromised on untying the sleeves of his sweater from around his waist and putting it firmly down on top of his books. None of this had anything to do with his father, who maintained strict neutrality on the subject of his son’s appearance. It was entirely a matter between Timothy, the time of day, and that unexpected gray felt hat on the hall table.

There were a dozen reasons for dad’s having come home early. There was nothing to get excited about. Timothy turned his back on the hall table and the hat, opened the door and went through into the living room. There was no one there, but he could hear his father’s voice in the kitchen, and, because the kitchen was a reassuring place, he felt better. He went on into the kitchen, shoving the door only part open and easing himself through it.

His mother was sitting on the kitchen chair beside the kitchen table. She was just sitting there, not doing anything. She never sat anywhere like that, doing nothing.

The formal, pressed-down feeling returned to Timothy and stuck in his throat.

He looked toward his father appealingly, but his father was leaning against the sink, with his hands behind him pressed against it, and staring down at the floor.

“Mom — ” said Timothy.

They both looked at him then, but it was his father who answered. He answered right away, as if it had to be said fast. “You’ll have to know, Tim,” he said, almost roughly. “It’s Bricky. He’s missing in action.” Missing in action. He had met the phrase so many times that it wasn’t frightening. There was no possible connection in his mind between “missing in action” and Bricky …

Missing in action. It was a picture on a movie screen, nothing more. Bricky, the invincible, would have bailed out, perhaps somewhere in the jungle. Or he would have nursed his damaged crate down to earth in a fantastically cool exhibition of flying skill, his men trusting him to see them through.

A hot, fierce pride surged up in Timothy. He wanted to tell his mother and father not to look that way; that Bricky, wherever he was, was safe. He wanted to reassure them, so that they would be smiling at him again and all the old cozy confidence would return to the kitchen.

His father was dragging words out, one by one. “The plane didn’t come back,” he said. “They were on a bombing mission, and they didn’t come back. We just got the telegram.”

An awful thing happened then. Timothy’s mother began to cry. He had never in his life seen her cry. It had never occurred to him that she was capable of it, and a monstrous chasm of insecurity yawned suddenly at his feet.

His father went over to her and got down on his knees on the kitchen linoleum, and he stayed there with his arm around her shoulders, murmuring, with his cheek against her hair, “Don’t, Ellen. Don’t, dearest.”

Timothy stood there in the middle of the floor with his hands jammed stiffly into his pockets and his eyes turned away from his father and mother. He was much more frightened by their sudden unfamiliarity than by what his father had told him. “Missing in action” was just words. His mother crying was a sheer impossibility, made visible before him.

He realized that he had to get out of the kitchen right away, because it was the place he had always been safest, and now that made it unendurable. He couldn’t do anything, anyway. Later, when his mother wasn’t — when his mother felt better, he could explain to her about Bricky being safe. He slid out of the room like a ghost, and, linked in their fear, neither of them even looked up.

In the front hall, he stopped for a moment. The spring sun outside was shining, bright and warm, on the street, and he knew exactly how the heat of it would feel slanting across his shoulders. But his mother had thought he ought to wear his sweater today. He wanted very badly to do something to make her feel better. He frowned and pulled the sweater on over his head, jamming his arms into the sleeves and resisting the temptation to push up the cuffs. It stretched them, his mother said.

He went slowly down the front steps, worrying about his mother. The words “missing in action” still meant exactly nothing to him. They were only another installment in the exciting war serial that was Bricky’s Pacific adventures, and there was not the slightest shadow of doubt in his mind about Bricky’s safe return, though he was eager for details. He guessed none of the other fellows at school had members of their family gallantly missing in action.

No, it wasn’t Bricky that made him feel funny in the pit of his stomach. The thing was he hadn’t known that grownups cried, and the discovery took a good deal of stability out of his world.

His mother might go on being frightened for days ahead, until they heard that Bricky was all right, and he would be tiptoeing around her in his mind all the time to make things better for her, and what he would really be wanting would be for things to be again the way they had been before.

He didn’t want to feel all unsettled inside. The way he felt now was the way he had felt the time they had been waiting to hear from his sister in California when the baby came. He had known quite well that Margaret would be fine and everything, but just the same, the baby’s coming had got into the house and filled it with uncertainties. Now it was the War Department. He was suddenly quite angry with the War Department. Bricky wasn’t going to like it, either, when he got back. He wouldn’t like mom worrying. Timothy wished now he had stayed a little longer in the kitchen and asked a few questions. He would have liked to know what that War Department had said, and, as he went down the street without any particular aim or direction, he turned it over and over in his mind.

He had walked back, without meaning to, to the vacant lot with the old shack on it, and it occurred to him that, while he had been shooting down those Jap planes in Bricky’s Hornet, his mother and father had been there in the kitchen. Looking like that.

He left the sidewalk and walked into the grassy tangle, scuffing his shoes through last autumn’s leaves. He would have liked some company, and he toyed for a moment with going over to Davy Peters’ house and telling him that the War Department had sent them a telegram about Bricky, but decided against it.

He sat down on the grass with his back against the wall of the shack. He could feel the rough coolness of the brown boards even through his sweater, and the sun spilled warmth down his front. It was unthinkable that the shack should ever be more comforting than the kitchen at home, but this time it was.

He wished he knew just what the telegram had said. There was something, he thought, that they always put in. Something about “We regret to inform you,” but maybe that was just for soldiers’ families when the soldier had got killed. He had seen a movie that had that in it once, and it had made quite an impression, because in the movie it was all tied up with not talking about the things you knew, and for days Timothy had gone around with a tightly shut mouth and the look of one who is giving no aid and comfort to the enemy. He had even torn the corners off all Bricky’s letters and burned them up with a fine secret feeling of citizenship, and then he had regretted it afterward, when he remembered it was only the United States APO address and no good to anyone. It was too bad, in a way, because they would have made a good collection. On the other hand, he already had eighteen separate and distinct collections, and the shelf in his room, the corner of the second drawer down in the living room desk, and the excellent location behind the laundry tub in the basement were all getting seriously overcrowded.

He wondered if maybe later he could have the telegram. He could start a good collection with the telegram, he thought. He would print on a piece of paper, “Things Relating to My Brother Bricky,” and paste it onto a box. He even knew the box he would use. It held his father’s golf shoes, but some kind of arrangement could be worked out for putting the shoes somewhere else. His father was very good about that sort of thing, once he understood boxes were really needed, and, later on, this one could hold all the souvenirs and medals and things Bricky would bring home.

The telegram, which maybe began “We regret to inform you,” would fit neatly into the box without having to be folded. It would go on with something about “your son, Lieutenant Ronald Baker,” and then there would be something more, not quite clear in his mind, about “He is reported missing in action over the South Pacific, having failed to return from an important bombing mission.”

Timothy scowled at a sparrow. There was another part that went with the “missing in action” part. Missing, believed — Missing, believed killed.

That was when it hit him. That was the moment when he suddenly realized what had happened — when the thing that the telegram stood for took shape clearly before him, not as something that had frightened his mother and made his father hold her very tight, but as something real about Bricky.

Bricky, his brother. Bricky, with whom he had sat a hundred times in this exact place and talked and talked, Bricky who went fishing with him, who showed him how to tie a sheepshank, who was going to help him build a radio when he came back.

“When he comes back,” said Timothy aloud, licking his lips because they had unaccountably gone dry. But suppose now that Bricky didn’t come back? Suppose that telegram was the end of everything?

It was the vacant lot and the shack that weren’t safe anymore. In the kitchen, he had known, without questioning it, that Bricky was all right. It was here, out in the open, that fear had come crawling. Bricky was dead. He knew Bricky was dead, and he was dead thousands of miles from anywhere, and they wouldn’t see him again ever.

Timothy sat there, and the pain in his stomach wasn’t anything like the pain you got from eating too much or being hungry. He rocked back and forth, not very much, but enough to cradle the sharpness of it, being careful not to breathe, because if he breathed it went down too far inside and hurt too much. If he could just sit there, maybe, not breathing

He couldn’t. There came a time when his lungs took a deep gulp of air without his having anything to do with it, and when that time came there was no way of holding out any longer.

Bricky was dead. He gave a great strangled sob and rolled over on his face, sprawling across the ground, and everything that was good and safe and beautiful quit the earth and left him with nothing to hold on to. He clung to the grass, shaking desperately with fear and pain and loss, and the immensity and the loneliness and the danger of being a human rolled over and over him in drowning waves.

Behind him, the shack, which only a little while ago had been a shelter for the sneak attack of Zero planes, was immobile and solid in the sunshine. It was only a shack in a vacant lot. The tumbled weeds and vines above which The Hornet had swooped and soared were weeds and vines, not a battleground for airborne knights.

It wasn’t that way. It wasn’t that way at all. It had nothing to do with a gallant plane, outnumbered but triumphant. It had nothing to do with the Bricky who had flown in his brother’s dreams, as safe and invincible as Saint George.

A plane was a thing that could be shot down out of the safe sky by murderous gunfire. Bricky was a man whose body could be thrown from the cockpit and spin senselessly down into cold water. It was a cheat. The whole thing was a cheat.

The war — this vague big thing that moved in shadowy headlines, in a glorious pageantry of medals and flags and brave men shaking hands — wasn’t that at all. He had thought it was something like the Holy Grail and King Arthur, that it shone with beauty and was very high and proud.

And it wasn’t. It was fear and this hollowed panic inside him, and it was not seeing Bricky again. Not seeing him again ever. That was why his mother had cried.

That was why his father’s voice had been so rough and quick. And it wasn’t to be endured. He breathed in shivering gasps, there with his face buried in cool-smelling grass and earth and the sun friendly and gentle on his shoulders that didn’t feel it anymore. It would go on like this, day after day and week after week. Bricky was dead, and the place where Bricky had been would never be filled in.

That was what war was, and he knew about it now, and the knowledge was too awful and too immense to be borne. He wanted his mother. He wanted to run to her and to hold to her tightly and to cry his heart out with her arms around his shoulders and her reassuring voice in his ears.

But his mother felt like this, too, and his father. There was no safety anywhere. No one could help him, except himself, and he was eleven years old. He didn’t want to know about all these things. He didn’t want to know what war really was. He wanted it to be a picture on a movie screen again, with excitement and glory and men being brave. Not this immense, unendurable fear and emptiness. He couldn’t even cry.

He was eleven years old, and he lay there face down in the grass, and he couldn’t cry. He groped for anything to ease him, and he thought perhaps Bricky’s plane hadn’t been alone when it crashed to the flat blue water. He thought that other planes might have been blotted out with it — planes with big red suns painted on them.

But even that didn’t do any good. There were men in those planes with the suns on them. Not men like men he knew, not Americans, but real people just the same. No one had told him that he would one day know that the enemy were real people, no one had warned him against finding it out.

He pressed closer against the ground, trying to draw comfort up from it, but he kept shaking. “Now I lay me down to sleep,” said Timothy into the grass. “Now I lay me down to sleep. Now I lay me — ”

It was a long, long time before the shaking stopped. He was surprised, at the end of it, to find that he was still there on the ground. He pushed away from it and sat up, his head swimming. The sun was much lower now, and a little wind had sprung up to move the vines around him so they swayed against the shack. The sweater felt good around his shoulders, and it was the sweater that made him realize suddenly that he couldn’t go on lying there waiting for the world to stop and end the pain.

The world wasn’t going to stop. It was going right on, and Timothy Baker was still in it. He would go on being in it, and the thing inside him would go on being the thing inside him. He would have, somehow, to live with that too. He would have to go back to the house, to the kitchen, to his mother and father, to school, to coming home and knowing that Bricky wouldn’t be there.

Timothy looked around. He felt weak and dizzy, the way he’d felt once after a fever. The shack was there, with no Jap Zeros behind it. The place where he had stood when he was being Bricky and The Hornet was just a piece of ground. His mouth drew in, with his teeth clipping his lower lip, while he stared. There wasn’t any escape. He would have to go back — along the sidewalk, up the path, through the front door, into the hallway, into the living room, into the kitchen. There wasn’t any escape from his mother’s eyes or his father’s voice. He knew all about it now, and he was stiff and sore from knowing about it.

He saw what he had to do. He had to go home and face that telegram. He got to his feet. He brushed off the dry bits of grass that had clung to the blurred wool of his sweater, and he pulled the cuffs around straight, so they wouldn’t be stretched wrong. Then he walked across the grass, out of the lot and onto the sidewalk, holding himself very carefully against the pain.

He held himself that way all the distance back, and when he got to his own front yard he was able to walk quite directly and quickly up the path and up the steps. He turned the doorknob and he went into the front hall. It was getting darker outdoors already, and the hall was dim. It was a moment before he realized that his father was standing in the hallway, waiting for him.

He stopped where he was, getting the pieces of himself together. He wasn’t even shaking now, and some vague kind of pride stirred deep down inside him.

He said, “Dad” dragging the monosyllable out.

“Yes, Timmy.”

“May I see the telegram, please?”

His father reached into his pocket and took out the brown leather wallet that he carried papers around in. The telegram was on top of some letters and bills, and it was strange to see it already so much a part of their living that it was jostled by business things.

Timothy took the yellow envelope and opened it carefully. There it was. “Lieutenant Ronald Baker, missing in action.” The stiff formality of the printed words made it seem so final that he felt the coldness and the fear spreading through him again, the way it had been at the shack. His mind wanted to drag away from the piece of paper, and he had to force it to think instead.

With careful stubbornness, he read the telegram again. It wasn’t really very much that the War Department said — just that the plane had not returned and that the family would be advised of any further news. He read the last part once more. Any further news. That meant the War Department wasn’t sure what had happened. Bricky might have bailed out somewhere. There had been stories in the newspaper about fliers who bailed out and were picked up later. That was a hope. Timothy weighed it carefully in his mind, not letting himself clutch at it, and it was still a hope. It was a perfectly fair one that they were entitled to, he and his father and mother.

He held his thoughts steady on that for a moment, and then he made them go on logically and precisely. Another thing that could have happened was that Bricky had gone down somewhere over land that was held by the Japanese. If that was it, Bricky might be a prisoner of war. Prisoners of war came back. That was another hope, and it was a perfectly fair one too.

He had two hopes, then. They were reasonable hopes, and he had a right to hang on to them very tightly. The telegram didn’t say “believed killed.” Frowning, he went through it in his head again, adding up as if it were an arithmetic problem. There were three things that the telegram could mean. Two of them were on the side of Bricky’s safety, and one was against it. Two chances to one was almost a promise.

Timothy drew a deep breath and handed the telegram back to his father. His father took it without saying anything, then he put his hand against the back of Timothy’s neck and rubbed his fingers up through the stubbly hair. For just a moment, Timothy turned his head, pressing close against the buttons of his father’s coat, then he pulled away.

“Can I go outdoors for a little while?” he said.

“Sure. I guess supper will be the usual time.”

They nodded to each other, then Timothy turned and went out of the house. He went down the steps, his hands jammed in his pockets, and began to walk along the sidewalk, feeling still a little hollow, but perfectly steady.

His heart fitted him again. It had stopped pounding against the cage of his ribs, and it didn’t hurt anymore. The old feeling of safety and comfort was beginning to come back, but now it wasn’t a part of his home or of the day. It was inside himself and solid, so that he couldn’t mislay it again ever. He pushed his hair away from his forehead, letting the wind get at it. The air was cooler now and felt good, and he had a vague moment of being hungry.

Then he looked around him. He was back at the vacant shack, and the shack had been waiting there for him to come. He eyed it gravely. Behind the shack were the Jap Zeros. They had been waiting for him too. He knew they were there and that their force was overwhelming. Timothy’s fingers reached automatically for the controls of his plane. His jaw tightened and his eyes narrowed, and he opened his mouth to let out the roar of motors.

And, suddenly, he stopped. His hand dropped down to his side and his mouth shut. He stood there quite quietly for a moment, as if he had lost something and were trying to remember what it was. Then he gave a sigh of relinquishment.

His fingers curled firmly around air again and closed, but this time they didn’t close on the controls of a machine. They closed on dangling reins.

“Come on, Silver, old boy,” said Timothy softly to the evening. “They’ve got the jump on us, but we can catch them yet.”

He touched his spurs to his gallant pinto pony, and, wheeling, he loped away across the sunlit plain.

Featured image: Illustration by Stevan Dohanos (© SEPS)

3D Printing the Old-Fashioned Way

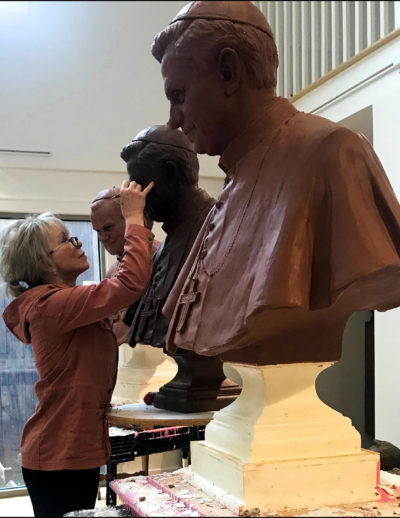

In 2014, a team of imaging experts with Smithsonian created the first-ever 3D-scanned presidential portrait. In a little over seven minutes with a sitting President Obama, the team was able to capture sufficient data to 3D-print a life-size bust of him that was an objectively accurate rendering of his features.

And yet, the resulting model was lacking a lifelike quality.

At least, that’s what bronze sculptor Carolyn Palmer says. She remembers thinking that her profession could be in jeopardy with the arrival of this new technology. Despite Obama’s abundance of soul and personality, the 3D-printed presidential portrait is “very cold,” Palmer says. “In my belief, the sculptor brings life into a piece.”

Her theory about the necessity of the artist in sculpture seems to ring true, even as leaps in technology have made such reproductions possible. Palmer is busier than ever, receiving a constant stream of commissions for sculptures in marble and bronze. Her bronze busts of Franklin D. and Eleanor Roosevelt are currently travelling with Rockwell, Roosevelt, and the Four Freedoms, an exhibit organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum. Opening last May in New York, the exhibition will have made stops in Michigan, Washington, D.C., Normandy, Houston, and Denver before it closes at the Rockwell museum in 2020.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series was originally published in this magazine as an artistic response to a speech President Roosevelt gave to Congress in 1941 on the eve of World War II. The paintings, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear, were published alongside essays by distinguished writers and became emblematic of the war effort.

“Who would say no to travelling with the Norman Rockwell Museum?” Palmer says. She visited the exhibit in New York, and she was thrilled to see her Roosevelt sculptures sitting among the works of the masterful American painter. Rockwell gained a reputation for painting faces so full of personality they seem as though they might come to life, and Palmer strives for a similar effect in her own work.

For 22 years, she has practiced the lost-wax method of casting bronze, which has itself been used for thousands of years. First, the artist creates a model in clay. This is covered with silicone rubber that will capture the finest details of the sculpture, then plaster for support. A wax model is made from this mold, which is then dipped into a ceramic slurry. The wax is “lost” when this new mold is heated. Finally, the bronze can be poured.

At every step, there are ample opportunities for disaster. A completed bronze sculpture requires an artist to oversee the work of many skilled artisans, and it can take months to finish. Palmer says she remains involved in the process at every step, particularly since she lost Edith Wharton. Her small clay model of the writer had been diligently sculpted with fine details, but it was destroyed when she handed it over to a newbie moldmaker.

Palmer received her degree in art education from Nazareth College, and she taught painting privately for a time while taking commissions for portraiture and logo design. She received her first opportunity to sculpt when one of her clients asked her to refer an artist to create a bronze Thomas Jefferson. “I said, ‘Oh please give me this opportunity, because I know I can sculpt!’ I offered to invest in the clays and told him if he didn’t like the piece he didn’t have to pay for it to go further into bronze,” Palmer says. Although she hadn’t studied sculpting much, Palmer remembered visiting her grandparents in Siesta Key when she was a little girl and carving forms at the beach: “Ever since I was a little girl I would make faces and people in the sand, and I would literally make them look like they were coming out of the sand.”

Since that first successful commission, Palmer has racked up an impressive resume of statuary that will stand in public and private spaces for generations. In 2015, she was chosen out of 68 sculptors to replace the infamous “Scary Lucy” statue in Lucille Ball’s hometown in New York. She has also completed likenesses of four popes, the Wright brothers, President Bill Clinton, Mario Cuomo, and Dr. William Osler. The last one might not ring a bell, but he is often described as the “Father of Modern Medicine” for his innovative practice of residency programs and bedside medical education. “There must not be a lot of Osler sculptors out there,” Palmer says, since she’s received orders on her Osler sculpture from around the world.

In the age of 3D-printing and automation, it might be difficult for many viewers of bronze and marble sculptures to appreciate the skilled process that goes into creating a lasting lifelike form. At best, they can be timeless, glowing tributes to humanity to marvel and inspire passersby. At worst, they can resemble the stuff of nightmares and serve as fodder for viral social media snark. The difference is all in the skill of the artist.