“If I Couldn’t Tell These Stories, I Would Die”: Lincoln and Laughter

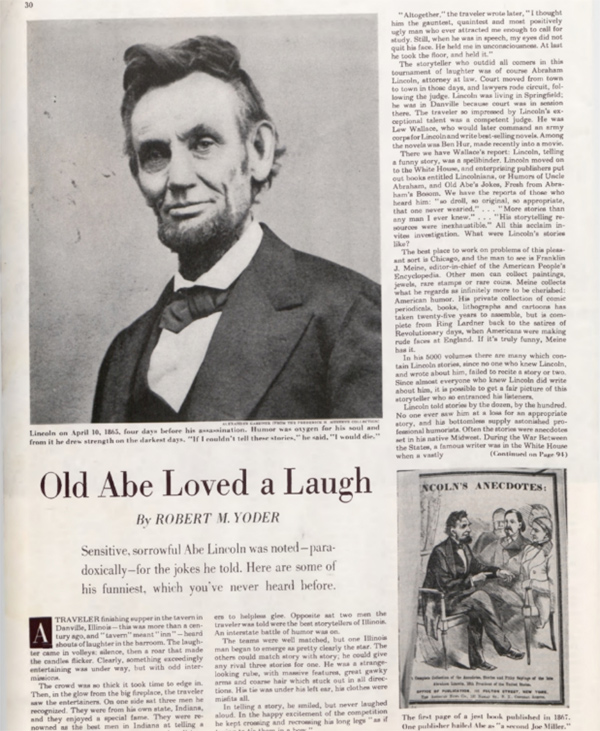

Imagine the unknown Lincoln. Picture the frontier lawyer who stepped onto the national stage — unkempt, gawky, blunt, speaking with a prairie twang in a high voice. And homely. Lord, he was homely.

Lincoln’s contemporaries, seeing him for the first time, might have noticed the same two things that struck Lew Wallace when he first saw Lincoln.

Later in life, Wallace was a best-selling author, a celebrated Union general, and a territorial governor. But in 1851, he was just another attorney who rode the judicial circuit with other lawyers. One evening, just after sundown, he rode into Danville, Illinois, and entered the local tavern. He found it crowded with people attending court business. As he edged his way into the crowd, he heard occasional bursts of laughter over the noise of the bar. Working his way toward the sound, he found that two teams of lawyers from Indiana and Illinois were have a joke-telling contest.

He took particular note of one of the contestants representing Illinois.

He arrested my attention early, partly by his stories, partly by his appearance. Out of the mist of years he comes to me now exactly as he appeared then. His hair was thick, coarse, and defiant; it stood out in every direction. His features were massive, nose long, eyebrows protrusive, mouth large, cheeks hollow, eyes gray and always responsive to the humor. He smiled all the time, but never once did he laugh outright. His hands were large, his arms slender and disproportionately long. His legs were a wonder, particularly when he was in narration; he kept crossing and uncrossing them; sometime it actually seemed he was trying to tie them into a bow-knot. His dress was more than plain; no part of it fit him… Altogether I thought him the gauntest, quaintest, and most positively ugly man.

What was even more memorable to Wallace was Lincoln’s ability to hold a room’s attention — and his apparently bottomless fund of jokes.

About midnight, his competitors were disposed to give in; either their stores were exhausted, or they were tacitly conceding him the crown. From answering them story for story, he gave two or three to their one. At last he took the floor and held it… Such was Abraham Lincoln. And to be perfectly candid, had one stood at my elbow that night in the old tavern and whispered: “Look at him closely. He will one day be president and the savior of his country,” I had laughed at the idea but a little less heartily than I laughed at the man. Afterwards I came to know him better, and then I did not laugh.

Humor was an essential part of Lincoln, and a critical element in his success. As a Congressional candidate, he used it to fire up crowds and put down hecklers. Running for the senate, his humor enabled him to score points off the well known and skilled politician, Stephen Douglas. When, for example, Douglas told a debate crowd that Lincoln was unqualified and unskilled, he added that Lincoln had once run a general store, selling cigars and whiskey. He added, “Mr. Lincoln was a very good bartender.” Lincoln retorted, “Many a time have I stood on one side of the counter… and sold Mr. Douglas whiskey on the other side.”

When Douglas accused Lincoln of being “two faced,” Lincoln shot back, “If I really had two faces, do you think I’d hide behind this one?”

Humor also proved valuable to Lincoln as president. As Robert M. Yoder noted in a 1954 Post article,

If a time-wasting friend lingered too long, Lincoln could disengage himself by telling a story which ended the conversation. He answered questions with stories; he avoided answering by telling stories. If the conversation headed in directions he didn’t like, he could change the subject with a story.

And, as we know now, humor helped Lincoln maintain his sanity.

“If I couldn’t tell these stories,” Lincoln once told a congressman — and gravely—”I would die.” Humor was of tremendous importance to this sensitive and sorrowful man; almost a sort of oxygen for the soul. It offended a good many citizens that Lincoln could joke in times so tragic, but those close to Lincoln understood the emotional process involved. It was jesting-that-I-may-not-weep.

Yoder offered several examples of Lincoln’s jokes. Some are familiar, but the number of unfamiliar stories suggests that Lincoln knew far more jokes than have been recorded.

When a courier appeared at the War Office to announce a major Union victory, the officers were surprised that Lincoln showed no excitement. Lincoln dismissed the courier and cheerfully told the men in the room,

Pay no attention to him… He’s the biggest liar in Washington. He reminds me of an old fisherman I used to know who got such a reputation for stretching the truth that he bought a pair of scales and insisted on weighing every fish in the presence of witnesses. One day a baby was born next door and the doctor borrowed the fisherman’s scales. The baby weighed forty-seven pounds.

Once when he found all his advisers solidly against him, he told this story:

A drunk wandered into a revival meeting and, after mumbling, “Amen,” a few times, fell asleep. As the meeting closed, the preacher cried, “Who are on the Lord’s side?” The congregation stood as one — all except the slumbering drunk. That shout didn’t wake him, but the next one did. “Who are on the devil’s side?” the revivalist cried. That roused the sleeper. Seeing the preacher standing, the drunk rose too. “I didn’t exactly understand the question,” he said warmly, “but I’m with you, parson, to the end.” He looked around at the silent crowd, all seated. “But it seems to me,” said the drunk, “that we’re in a hopeless minority.”

Lincoln’s easy use of humor changed America’s taste in politicians. Previously, Americans had preferred solemn, humorless men with the gravity of Old Testament prophets. We now expect our legislators and presidents to occasionally tell, and laugh at, jokes. We believe a sense of humor reflects a sense of reason and proportion, and an ability to perceive the outrageous.

In many regards, Lincoln was a man ahead of his times. He saw, sooner than most of his contemporaries, what we all recognize: laughter is necessary for keeping our sanity.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Easter Madness Takes Manhattan

Every Easter, New York natives and tourists gather on Fifth Avenue for the annual Easter Parade. The parade is less of an organized march and more of a stroll to see and be seen. Bonnets feature everything from bunny ears to bee hives. Men sport straw boaters and bedazzled top hats, and pets get in on the action, too (reluctantly, by the looks of it).

The history of the parade dates back to the mid-1800s, when churchgoers would take to Fifth Avenue like a Paris fashion show runway after morning services. Locals would gather along the avenue to admire their latest attire. By the middle of the 20th century, more than million people would show up.

In the April, 9, 1955, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, writer Rufus Jarman explored the parade’s fanciful behavior in “Manhattan’s Easter Madness.” Jarman reported that the police would try to maintain some semblance or order, including the ouster of “poseurs in weird raiment and women wearing ridiculously exhibitionistic hats.”

But the mid-century paraders would not be denied. One woman’s hat featured “a model of the Last Supper, the Crucifixion, a troop of Roman soldiery and a live parakeet.” There were kids in space suits, dogs with pipes, and a man in a silver sombrero hawking trips to Mexico.

Jarman proclaimed the whole affair to be completely out-of-hand. The proof? “These things horrified even New Yorkers.”

Featured image: April 7, 1906 Easter cover by J.C. Leyendecker (©SEPS)

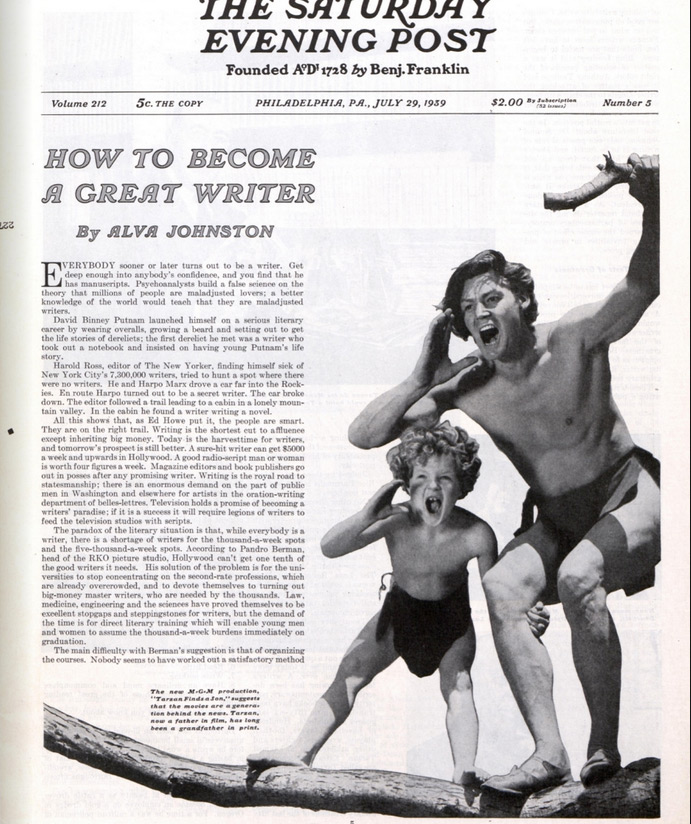

Edgar Rice Burroughs on How to Become a Great Writer

This article was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on July 29, 1939.

Is any other town in America named for a character in fiction?

Everybody sooner or later turns out to be a writer. Get deep enough into anybody’s confidence, and you find that he has manuscripts. Psychoanalysts build a false science on the theory that millions of people are maladjusted lovers; a better knowledge of the world would teach that they are maladjusted writers.

David Binney Putnam launched himself on a serious literary career by wearing overalls, growing a beard and setting out to get the life stories of derelicts; the first derelict he met was a writer who took out a notebook and insisted on having young Putnam’s life story.

Harold Ross, editor of The New Yorker, finding himself sick of New York City’s 7,300,000 writers, tried to hunt a spot where there were no writers. He and Harpo Marx drove a car far into the Rockies. En route Harpo turned out to be a secret writer. The car broke down. The editor followed a trail leading to a cabin in a lonely mountain valley. In the cabin he found a writer writing a novel.

All this shows that, as Ed Howe put it, the people are smart. They are on the right trail. Writing is the shortest cut to affluence except inheriting big money. Today is the harvest time for writers, and tomorrow’s prospect is still better. A sure-hit writer can get $5,000 a week and upwards in Hollywood. A good radio-script man or woman is worth four figures a week. Magazine editors and book publishers go out in posses after any promising writer. Writing is the royal road to statesmanship; there is an enormous demand on the part of public men in Washington and elsewhere for artists in the oration-writing department of belles-lettres. Television holds a promise of becoming a writers’ paradise; if it is a success it will require legions of writers to feed the television studios with scripts.

The paradox of the literary situation is that, while everybody is a writer, there is a shortage of writers for the thousand-a-week spots and the five-thousand-a-week spots. According to Pandro Berman, head of the RKO picture studio, Hollywood can’t get one tenth of the good writers it needs. His solution of the problem is for the universities to stop concentrating on the second-rate professions, which are already overcrowded, and to devote themselves to turning out big-money master writers, who are needed by the thousands. Law, medicine, engineering and the sciences have proved themselves to be excellent stopgaps and steppingstones for writers, but the demand of the time is for direct literary training which will enable young men and women to assume the thousand-a-week burdens immediately on graduation.

The main difficulty with Berman’s suggestion is that of organizing the courses. Nobody seems to have worked out a satisfactory method of training writers to write. Colleges are good on punctuation marks, but not on what to put between them. Famous writers seem to have left few hints that are useful to beginners. Ring Lardner said it was a matter of selecting pencils of the right colors. Anthony Trollope said it was a matter of attaching the writer’s pants to the chair with beeswax. Goethe attributed his output to a chair in which it was impossible to get into a restful position. In the vast literature about Dr. Samuel Johnson, only one practical rule of writing is to be found, and Doctor Johnson had that from an old schoolmaster; the rule being that, if you think any sentence you write is particularly good, strike it out. Dickens picked up his technique by accident. As a Parliamentary shorthand reporter during the decadence of parliamentary oratory, he learned the comic effect of presenting trivialities in ornate and sounding prose.

Tests of Greatness

The subject has to be simplified before the universities cap turn out prose masters on belt conveyors. A new approach to the problem would be to take the greatest living writer and make a thorough analysis of the factors, which caused his greatness. Because of differences of opinion as to who is the greatest living writer, it is necessary to adopt arbitrary tests to identify him.

These tests are:

- The size of the writer’s public.

- His success in establishing a character in the consciousness of the world.

- The probability of his being read by posterity.

Judged by these tests, Edgar Rice Burroughs is first and the rest nowhere.

No other literary creation of this century has a following like Tarzan. Another character with a worldwide public is Mickey Mouse, but he belongs to a different art. The only other recent works of imagination in this class are Charlie McCarthy and The Lone Ranger, but their vogue is confined to the English-speaking peoples and they are still novelties rather than assured immortals.

Twenty-five million copies of the Tarzan books have been sold. Taman has established his durability; the first book on the ape boy came out a quarter of a century ago, and he is today more popular than ever. A writer’s foreign following has been described as a contemporary posterity; Tarzan books have been translated into fifty-six languages and dialects. Hundreds of baseball players, football players, wrestlers, fighters and other athletes are nicknamed Tarzan. Extra-large schoolboys are called Tarzan in admiration, and undersized ones are called Tarzan in derision. Sherlock Holmes, Peter Pan, Pollyanna and Babbitt are perhaps the only literary creations of the last fifty years whose names are rooted in the English language as strongly as Tarzan; and Tarzan is a household word on every continent and on the larger islands from Iceland to Java.

Tarzan is a pillar of the American fiscal system. Through his author, his motion-picture company, his cartoon-strip syndicate, his radio sponsors and his various other concessionaires, the African ape boy contributes enough in taxes to pay the salaries of most of the United States senators.

What Makes Him Click

Burroughs is clearly the man to tell the 130,000,000 American writers how to write. His life story ought to be the supreme textbook. The main rules for literary training that can be gathered from the experiences of Burroughs are:

- Be a disappointed man.

- Achieve no success at anything you touch.

- Lead an unbearably drab and uninteresting life.

- Hate civilization.

- Learn no grammar.

- Read little.

- Write nothing.

- Have an ordinary mind and commonplace tastes, approximating those of the great reading public.

- Avoid subjects that you know about.

Burroughs had been an ill-paid employee and an unsuccessful small businessman for fifteen years before he wrote a word of fiction. The great difficulty in basing a college training on his rules is that of compressing into four years all the dullness, wretchedness and futility which it took Burroughs fifteen years to assimilate.

Burroughs started at twenty as a cattle drover and then became an employee on a gold dredge in Oregon. For a time he was a railroad policeman in Salt Lake City. He put in stretches as an accountant, as a clerk and as a peddler. His most important position was that of head of the stenographic department of Sears-Roebuck, in Chicago. A docile employee, he was never fired. An inveterate reader of help-wanted ads, he was constantly obtaining new positions not quite equal to his old ones. Added to that, he was always ready to join his own pennilessness to the pennilessness of some other man, and to found a partnership on any naïve dream of avarice.

King of the Pot-and-Pan Trade

Combining their resources of no capital, no experience and no contacts, Burroughs and a partner founded an advertising agency, which failed. Having no experience with salesmanship beyond that of being repulsed by housewives when he tried to sell sets of Stoddard’s Lectures, Burroughs wrote a correspondence course in salesmanship. After studying by correspondence for a few weeks, his students were to be graduated into fieldwork. Small stocks of aluminum pots and pans were sent to them with instructions to sell them from door to door and remit the money to the home office.

Burroughs and his partner thought there were millions in it. They regarded themselves as aluminum kings about to corner the pot-and-pan trade with the help of peddlers who would pay tuition fees for the privilege of peddling. But the students all quit when they got to the fieldwork stage. Some failed to send back either the money or the pots and pans.

The Burroughs family had been rich when Edgar was a boy, but had lost its money. His allowance at prep-school had been $150 a month. During his entire business career he never earned as much as his prep-school allowance. Twice he was compelled to pawn his family heirlooms in order to buy food for his wife and children. His failure as a businessman was so complete that he was reduced to earning a living by writing hints on how to become a successful businessman.

The businessman’s bible three decades ago was System, the Magazine of Efficiency. It was a pioneer in introducing charts and graphs. Many businessmen worshiped charts and graphs as religious symbols. It was their belief that, if they stared long enough at these mystic curves and angles, red ink would turn into black.

A new department was introduced by the magazine. On payment of fifty dollars a year, a businessman could write to the magazine as often as he liked, and receive detailed advice on his business problems. Burroughs was hired to give the detailed advice. There was also a detailed-advice department for bankers, which was handled by a youth of twenty-one years. Burroughs sat at his desk from morning until night, writing counsel to merchant princes and captains. He used words that rumbled with portentous business wisdom, but were too vague to enable any industrial baron to net on them. Burroughs had a conscience, and it was always his fear that, if his advice ever became understandable, it would land his clients in the bankruptcy courts. With his letters he would enclose some of the awe-inspiring hieroglyphics now known as “barometrics.”

Burroughs’ advice never brought a complaint, and he may have been as good as anybody else in this field. Nothing is definitely known on the subject today except that the more the charts and graphs flourish, the faster business decays.

Burroughs’ first contact with literature came in 1911 through his connection with Alcola, a cure for alcoholism. Alcola cured alcoholism all right, but the Federal Pure Food and Drug people took the position that there were worse things than alcoholism, and forbade the sale of Alcola.

One of Burroughs’ duties in the Alcola firm was that of putting advertisements in the pulp fiction magazines. He bought the magazines in order to make sure that his ads were printed. He detested fiction, but when he looked at the ads some of the reading matter entered his field of vision. His reaction was approximately that of Dean Swift, who, under similar circumstances, exclaimed, “No man alive ever writ such damned stuff.”

His next thought was that, if this was literature, any man could be a man of letters if he would abandon his mind to it. He wrote a novel. Thomas Newell Metcalf, editor of the All-Story Magazine, accepted it and sent Burroughs a check for $400. It was published as a serial in All-Story in 1912, under the title of Under the Moon of Mars.

Metcalf wanted to make a Sir Walter Scott out of Burroughs. He induced him to spend months of research on the Wars of the Roses. The result was a novel entitled The Outlaw of Torn. Metcalf rejected it.

Burroughs saw the folly of research. He had located his first novel on Mars because nobody knew the local color of that planet or the psychology of the Martians, and nobody could check up on him. A similar motive influenced him partly in writing his first Tarzan book, Tarzan of the Apes. He created a new race of apes, bigger than gorillas, and placed them in an unknown part of Africa. He knew that nobody could trip him up on the psychology, customs and language of his own private anthropoids.

For African local color he read Stanley’s In Darkest Africa. He got his flora all right, but he made a blunder in his fauna. One of his important characters was Sabor, the tiger. There are no tigers in Africa. Letters from readers were printed in All-Story on this point. A man in Johannesburg confounded the critics, however, by writing that everybody in Africa referred to leopards as tigers. Nevertheless, Burroughs later changed Sabor to a lioness. He got a check for $700 from All-Story for Tarzan of the Apes.

Burroughs had by this time retired from his last business, that of selling a pencil sharpener, and was devoting all his time to writing. His business career had, by its dreary futility, been a genuine literary apprenticeship. During his last few years in commercial pursuits, life had become almost intolerable to him.

He was too poverty-stricken to pay for any of the tired businessman’s relaxations, but he hit upon a free method of making himself feel better. When he went to bed he would lie awake, telling himself stories. His dislike of civilization caused him frequently to pick localities in distant parts of the solar system. Every night he had his one crowded hour of glorious life. Creating noble characters and diabolical monsters, he made them fight in cockpits in the center of the earth or in distant astronomical regions. The duller the day at the office the weirder his nightly adventures. His waking nightmares became long-drawn-out action serials.

The Delirium Road to Success

Psychiatrists consider these reverie addicts as borderline cases. If Burroughs’ family had known of his mental state, they would have called in a medical man, who would have probably insisted on having his teeth out, according to the fashionable method of treating such patients in 1911. Twenty years later, Burroughs would have been advised to save up his money for a few years and go to a psychoanalyst, who would have cured him of an incipient $10,000,000 affliction. A raise of twenty-five dollars a month in 1911, according to Burroughs’ estimate, would have made him happy and caused him to put in nights of sound, refreshing slumber, instead of constructing penny-dreadful deliriums for himself.

Burroughs had given away serials to himself for five years or more before he learned that he could sell them. He had become a master of the slaughterhouse branches of fiction. It is clear from reading the Tarzan and other Burroughs books that he devoted little of his twilight sleep to tea-table and boy-meets-girl imbroglios.

Five years of dark and bloody mysteries gave his pen a high professionalism in pyramiding climaxes and piling up horror; but he was an awkward novice when the structure of his novel required him to introduce scenes of society life or hearts-and-flowers passages. Burroughs is great when Tarzan has a half nelson on a lion or a gorilla, but he has no talent for drawing-room hubble-bubble or boudoir hanky-panky. There is a trace of Homer in him, but not any Noel Coward.

In Tarzan of the Apes the reader can put his finger on the passages where Burroughs is the dream-disciplined artist and on the passages where he is the self-conscious amateur. He wanted to endow his ape-reared infant with a magnificent heredity. He was under the impression that the way to have a glorious moral, mental and physical inheritance was to be a scion of the British aristocracy. So Tarzan’s parents were Lord and Lady Greystoke, the flower of the old nobility. Burroughs created them out of condescending sawdust.

It is obvious that Burroughs in his nightly trances had wasted no time messing around with lords and ladies. The Burroughs noblemen cause the reader to turn instinctively to P. G. Wodehouse for a sympathetic picture of the British aristocracy. But when the real Burroughs gets to work on his wild boy, his colossal anthropoids, his giant carnivora and his cannibals, it is not difficult to see why 3,000,000 copies of Tarzan of the Apes have been sold and why Tarzan is the best-known literary character of the twentieth century.

Burroughs says that his ordinariness explains his success. When he wrote his first novel for All-Story, he used the nom de plume of Normal Bean, meaning common head. By accident the editor changed it to Norman Bean. Burroughs was unwilling to use his own name at the time because he thought it would hurt his standing in the unsuccessful business world. He believes today that his novels are in demand because the things that interest him are bound to interest the ordinary Undoubtedly a certain galloping commonplaceness is one of his assets, but he has others. He did not win his world public solely through mediocrity. There are pages of his books which have the authentic flash and sting of story telling genius.

One brilliant passage is that in which the half-grown Tarzan identifies himself as the being who is reflected in a pool of water. Tarzan had already had reason to suspect that he was not a trueborn ape. Gazing at himself in the waters, he discovers what a poor relation of the higher anthropoids he really is. Burroughs is in a high literary vein when he describes the boy’s chagrin in comparing his parody of a countenance with the pretentious physiognomies of his playmates. Instead of nostrils that spread half across his face, he had a despicable imitation of an organ of smell. He had trifling bits of ivory where competent tusks should have been. Self-pity overwhelmed him when he discovered that his eyes were an insipid gray instead of being big, black and blofldshot. On realizing that he was hairless like a snake, he plastered himself from head to foot with mud.

Tarzan had already suspected that he was not a true ape, because he had discovered in a deserted cabin a number of kindergarten books with pictures of animals. He had begun to fear that he resembled the apes less than he resembled another animal, whose picture was always printed with what appeared to be three little bugs — B, O, and Y. The painful conviction was forced upon him that he was a B-O-Y.

Using these three bugs as a clue, Tarzan works out the secret of all the twenty-six bugs in the alphabet. He learns written English without knowing how to pronounce it. Burroughs’ handling of Tarzan’s self-education is better than the cipher sequences in The Gold Bug or The Dancing Men.

Tarzan’s discovery that he is a member of the human species later lands him in a beautiful ethical dilemma. Having killed an African tribesman, Tarzan is about to help himself. Certain doubts assail him. His bringing up had taught him that eating a member of one’s own species was not done. He has eaten raw gorilla, but the gorilla does not belong to his set. Tarzan now knows himself to be a man, and he recognizes the dead African as a man. On the other hand, Tarzan is hungry, and his political sympathies are all with the apes. It is a pretty case of conscience, and Burroughs does justice to it. In the end Tarzan takes the high ethical stand and never refreshes himself with an African.

Tarzan Gets Slapped

One sequence in Tarzan of the Apes will bear comparison with the much admired passage in Gulliver’s Travels in which the Lilliputians, in an official report on the effects removed from Gulliver’s pockets, suggest that his watch is his god because of the frequency with which he consults it. Tarzan sees Kulonga, son of a savage chief, cook a wild boar and eat it. Tarzan knows fire only as Ara, the lightning. He cannot understand why anybody would spoil raw meat by plunging it into fire. He concludes that Kulonga is a friend of the god of lightning and is sharing the wild boar with him. There is occasionally a touch of poetry in Burroughs, as in describing Tarzan’s grass-woven lasso as “his long arm of many grasses.”

Another source of the author’s strength is his strong grip of character. Not only Tarzan but the apes and animals are highly individualized beings who seldom step out of character. Burroughs edits the Tarzan movies and newspaper strips to see that no liberties are taken with the Tarzan psychology. In one movie scene, for example, Tarzan threw his head back and laughed long and boisterously. “Strike it out,” ordered Burroughs. Tarzan, in spite of his violent activity, is as reserved and contemplative as Hamlet. Nothing could be farther from his personality than brainless uproariousness.

One of the handsome passages in Tarzan of the Apes is the ape-bred boy’s first encounter with white womanhood. Tarzan rescued the heroine, a glamorous but educated American girl, from the clutches of a mate-hunting giant ape. The bronzed and sun-baked Tarzan, accustomed to seeing none but ape women and blacks, was conscious of a sudden prejudice in her favor, in spite of her white body. He wanted her to know that he was favorably disposed toward her. His good will took the form of pawing and nuzzling. She slapped him. Tarzan was astonished. He had assumed that, when a member of a species showed a nice spirit toward another member of the same species, that spirit would be reciprocated. He could not understand why she was returning evil for good.

The Boy Who Escaped Grammar

Burroughs was told that Kipling liked Tarzan and supposed that Tarzan was patterned after Mowgli of The Jungle Book. According to Burroughs, Taman is a literary descendant, not of Mowgli but of Romulus and Remus, who got such a raising from a she-wolf that they founded Rome. Burroughs credits himself with only one stroke of genius—the naming of Tarzan. The impact of those two syllables on the eardrum is, in his opinion, largely responsible for the world success of the Tarzan books. This is one of the few literary secrets of Burroughs that is communicable. In christening his characters he works with syllables as some composers work with musical notes. He tests one sound against another until, after trying perhaps hundreds of combinations, he has a name that rings like a fire bell.

The early life of Burroughs was more interesting than his business career, but it furnishes few hints toward becoming a great writer. His father, who had been a major in the Civil War, grew rich in the distilling business. Later he became a manufacturer of electrical batteries. He had a habit of reading aloud, which partly caused young Edgar’s aversion to literature. When, for example, his father read Dombey and Son, Edgar hated Dombey and had the impression that Dombey and Dickens were one and the same person. When he learned the difference,it was too late for him to overcome his ingrained prejudice against Dickens. He has also cherished a lifelong dislike for Shakespeare, but is big enough to state that he assumes it to be his fault rather than the poet’s.

Burroughs’ escape from grammar was a lucky accident. He was sent first to a private school in Chicago which held that the teaching of English grammar was nonsense and that students should absorb grammar through Latin and Greek. Edgar absorbed no Latin and Greek. He was then sent to Phillips Andover, which, assuming that all freshmen were thoroughly drilled in grammar, ignored that subject. Phillips Andover quickly waived on young Burroughs, and he was sent to military academy, which paid no attention to grammar. Edgar thus became an uninhibited writer, free from the anxieties about moods and tenses which kill spontaneity. Burroughs doesn’t know whether he is grammatical or not, and cares less. He always writes or dictates at top speed in order to get his thoughts on paper while they are fresh and hot. No grammar-scared writer can do that. Burroughs never makes corrections unless he finds an inconsistency in his development of plot.

The battery business led the elder Burroughs to become interested in an electrical horseless carriage. Edgar demonstrated it at the World’s Fair, in 1893. The only time he ever felt that he amounted to something was when he drove a nine-seater horseless surrey about the fairgrounds, starting runaways every hundred feet or so.

A Youthful Glory Seeker

In his youth Burroughs had a craving for glory. He preferred the military variety because his father had been a soldier. After graduating from the Michigan Military Academy he joined its faculty as a cavalry instructor. After the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5, China, which had been defeated because her armament consisted largely of drums and dragon banners, started to reorganize her army. Burroughs sought a commission in the Chinese army, but failed. Later he obtained a commission in the Nicaraguan army, but his family interfered. At the age of twenty he enlisted in the Seventh Cavalry and was sent to Arizona against Geronimo. Instead of cavalry charges, however, the campaign consisted mainly of ditch-digging. Wires were pulled, and, because Burroughs had enlisted while under age, he was discharged. In 1898 he volunteered for the Rough Riders, but received a polite letter of regret from Theodore Roosevelt.

During his brief Regular Army service, Burroughs had committed two grave infractions of the military code. On sentry duty, he was required to shoot to kill if anyone disregarded his warning of “Halt, or I fire.” His warning was twice disregarded, but Burroughs did not shoot. In each case he wrongfully saved the life of a drunken member of his own outfit. He escaped disgrace, his unsoldierly conduct never becoming known.

From the Army Burroughs went directly into cow handling, and then into gold dredging. Years later, after establishing himself as a writer about imaginary worlds and countries, he wrote The Bandit of Hell’s Bend, based on his Western experience. This was a violation of his custom of not writing things personally known to him; but things personally known to him; but Alexander Grosset, of the publishing house of Grosset and Dunlap, pronounced The Bandit of Hell’s Bend the greatest Western ever written.

The old craving for glory was roused in Burroughs only once after the Spanish-American War. He happened to see the regal state in which the president of the Oregon Short Line traveled. He took the only railroad job he could get. In hot pursuit of glory, Burroughs chased bums out of boxcars in the Salt Lake City railroad yards for six months. But the idea of becoming a railroad president—last of his high ambitions—faded, and he drifted into the business career which punished him until he took refuge in literature.

The first Tarzan story did not immediately make Burroughs rich. The idea of bringing it out in book form was rejected by publishing houses, one reason being that they felt that the title, Tarzan of the Apes, would shock refined people. Burroughs wrote a sequel, The Return of Tarzan. It was declined by the Munsey publications, without the knowledge of Bob Davis, editor-in-chief of that organization.

Davis was furious when the Tarzan sequel was printed in a rival magazine. The famous editor took Burroughs under his wing and insisted on publishing everything he wrote. Even Davis, however, did not see the future of Tarzan. He induced Burroughs to cause the original Tarzan to assume his title of Lord Greystoke and take his seat in the House of Lords, while the series was carried on with the son of Tarzan. This caused confusion, and Burroughs finally went back to Tarzan the First. According to rigid rules of biology, the African wild boy is now a grandfather.

In less than, a year after his first work was published, Burroughs was a big pulp name and a ten-cents-a-word writer. As his literary labor consisted largely of transcribing from memory the old phantasmagorias with which he soothed himself during his business life, his production was large. He was making more than $20,000 a year before his first book was published. On his banner day he wrote 9100 words— $910 worth.

An International Institution

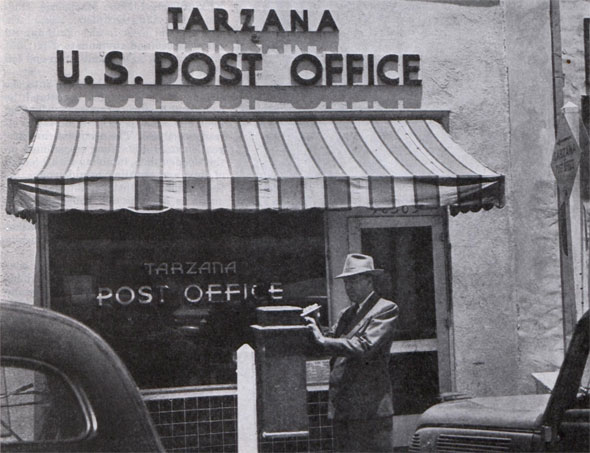

Big money did not immediately soften Burroughs’ hatred of modern life. His great aim was to escape from civilization, and, as soon as he had money, he went to Southern California. In 1919, after he had become wealthy, Burroughs bought the 600-acre Harrison Gray Otis ranch in the San Fernando Valley and founded the town of Tarzana, about half an hour’s auto ride from Hollywood. He delighted to ride, stetson on head, gun across saddle, over his hills and through his valleys and his canyons.

He started to ranch on a large scale with pedigreed animals. It was necessary to write furiously to support the ranch. Scarcity of wells and springs was the trouble. Water had to be brought in from the outside. After some experience with water rates, he found it would be cheaper to take his cattle to a soda fountain. The ranch was turned over to the El Caballero Golf Club, which failed. After running it as a public golf course for a while, Burroughs sold out.

Burroughs had been writing four years before a publishing house would take a chance on printing his novels in book form. The late J. H. Tennant, editor of the New York Evening World, had read Tarzan of the Apes in All-Story and bought the right to print it in his newspaper. Other papers followed suit, and Tarzan fans became an important bloc in the community. A. C. McClurg .& Co., one of the many publishers which had previously rejected Tarzan of the Apes, began publishing the Tarzan books and then other Burroughs novels. Millions of boys took to leaping from limb to limb and from tree to tree. The nation resounded with the Tarzan yell and the snapping of collarbones.

Today Burroughs has forty nine books in print. The sales have exceeded 30,000,000 copies. The Tarzan books are still in great demand in nearly every part of the world except Germany. In 1925 Burroughs was taking more royalties out of Germany than any foreign author, but in that year a German writer printed a book entitled Tarzan the German Devourer. During the World War, Burroughs had, in Tarzan the Untamed, caused Tarzan to do his bit by capturing German officers and feeding them to lions. The sensitive Teutons boycotted Burroughs after 1925.

Tarzan is a radio star today. The Tarzan comic strip is printed in about 150 American newspapers and forty foreign ones, including journals in Java and Ceylon. Tarzan has been a great money-maker in the movies for more than twenty years. Johnny Weissmuller is the ninth actor to play the part in the films.

Tarzan’s importance in the films increased greatly in 1932, when the late Irving Thalberg took charge of his career. Thalberg and Burroughs agreed that Tarzan pictures should be great spectacles and should come out once a year, like a circus. Thalberg’s first two pictures cost more than a million each, and the third, Tarzan Escapes, cost more than a million and a half. After Thalberg’s death, the Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer Company dropped Tarzan as too expensive. But the final audit showed that Tarzan Escapes had grossed more than $2,000,000, and the series was resumed.

The expensiveness of the Tarzan films lies partly in the nature of things and partly in the maniacal perfectionism of Hollywood. In the last picture, Tarzan Finds a Son, the producers wanted an effect of steam rising from a lake. They ransacked the country for steamy lakes and at last found the one they wanted in Florida. The lake refused to steam for them. They found that it would steam only on certain days and then only for about fifteen minutes in the morning. It took the location company seven days to get the pictures they wanted.

Most of the Tarzan scenes are taken out of doors. Bad weather causes losses running into hundreds of thousands of dollars in salaries of actors, technical men and mobs of extras. But the greatest expense is that of getting animals to perform. In making the last picture a lion cost the company tens of thousands of dollars by refusing to chase a small boy. The lion would either walk or lie down or lope off in the wrong direction. When he finally took after the boy, the boy forgot to run. The pay roll ran wild for ten days before the scene could be shot. Flamingos, zebras and other live items of African background, after hours had been consumed in maneuvering them into their places, walked off the set just before the cameras started.

It took weeks to teach the big elephant, Queenie, to limp when she was supposed to have been shot in the foot. In the meantime the baby elephant, Bea, was limping sympathetically, and it took weeks to break her of the habit. A herd of hippopotamuses broke out of their stockade in Sherwood Lake and ate up $25,000 worth of horticulture in the neighborhood. Fresh ostrich eggs, which were used by Tarzan’s mate in making omelets, cost twenty-five dollars each.

MGM spared no expense on the Tarzan yell. Miles of sound track of human, animal and instruments sounds were tested in collecting the ingredients of an unearthly howl. The cry of a mother camel robbed of her young was used until still more mournful sounds were found. A combination of five different sound tracks is used today for the Tarzan yell. These are:

- Sound track of Weissmuller yelling, amplified.

- Track of hyena howl, run backward and volume diminished.

- Soprano note sung by Lorraine Bridges, recorded on sound track at reduced speed; then re-recorded at varying speeds to give a “flutter” in sound.

- Growl of dog, recorded very faintly.

- Raspy note of violin G-string, recorded very faintly. In the experimental stage the five sound tracks were played over five different loud-speakers. From time to time the speed of each sound track was varied and the volume amplified or diminished.

When the orchestration of the yell was perfected, the five loudspeakers were played simultaneously and the blended sounds recorded on the master sound track. By constant practice Weissmuller is now able to let loose an almost perfect imitation of the sound track.

In some advance publicity on the latest picture, Tarzan Finds a Son, MGM let it become known that Tarzan’s mate, Jane Porter, was to die. Burroughs was in consternation. This was an awful tragedy to him. His second best literary property was to be callously abolished by a film company. He looked up his contract. It stipulated that MGM could not kill, cripple, or undermine the character of Tarzan, but it was silent as to his mate. Burroughs regarded Tarzan as a fundamental monogamist and would not look forward to building up a new romance around a widower. But shrieks from the fans all over the country changed MGM’s mind, and Jane’s life was spared. The movie company had nothing against Jane, but it was tired of losing the services of Maureen O’Sullivan, who played Jane, during the interminable months while bad weather and perverse animals were delaying Tarzan productions.

The movie company is sending an expedition to Africa for the next Tarzan picture. It is planned to make the okapi, least seen and known of large animals, a sort of co-star with Johnny

Weissmuller. The okapi is a relative of the giraffe and the extinct samotherium. It stands five feet high at the shoulders; its colors are purple and puce; its legs are striped like a zebra’s.

Dwelling in dense forests, rendered almost invisible by its coloring, the okapi — pronounced “okappi“ — is the cameraman’s toughest assignment. Burroughs has been asked to accompany the expedition for publicity purposes and is inclined to accept. He began to take a great interest in Africa after writing his first few books about it. He has a library on the subject today and has become a sort of authority on Africa. He would like to see some of the country about which he has written hundreds of thousands of words. Aside from brief excursions to Canada and Mexico and one trip to Hawaii, he has never been out of the United States.

Burroughs is sixty-three years old. He is a little above medium height, and powerfully built. Horseback riding and tennis keep him fairly rugged, but he is always planning more strenuous measures to take off the extra ten pounds.

He leads a fairly busy life at his office at Tarzana, where he not only knocks off two novels a year but superintends the publication of his books and his other Tarzan enterprises.

The creator of Tarzan has a big poker face surmounted by close-cropped iron-gray bristles. He still looks a little military. Interviewers always complain that he does not look literary, but it is a convention of the interviewing craft to expect writers to resemble either Robert Louis Stevenson or Irvin S. Cobb.

Portrait of a Realist

There is probably less literary foppery about Burroughs than about any other living writer. He has enough fame for a thousand ordinary lions of the literary teas, but it has never meant anything to him except as it has boosted royalties. He has known few writers personally and does not like them as a class; he thinks they spend their leisure sitting around and trying pathetically to say smart things.

Burroughs travels with a non-Tarzan-reading set. If a personal friend ever tells Burroughs of looking into a Tarzan book, he mentions the matter with an apology or a hearty laugh. “My son,” says the friend, “left it lying open on a table and I happened to pick it up. Ha! Ha! Ha! I read a little of it. Ha! Ha! Ha!” If anybody compliments him to his face, Burroughs bristles, supposing that he is being heckled. But he is not mortified to learn that over in Japan little boys have been named Edgar after the author of Tarzan.

In his office at Tarzana, Burroughs has a soundproof study. At first that seems to be in the classic literary tradition. It recalls Carlyle’s everlasting campaign to fortify his study against the crowing of the demon fowls. Burroughs, however, soundproofed his study so that he can dictate his novels to a recording machine without disturbing his secretarial staff in the adjoining room.

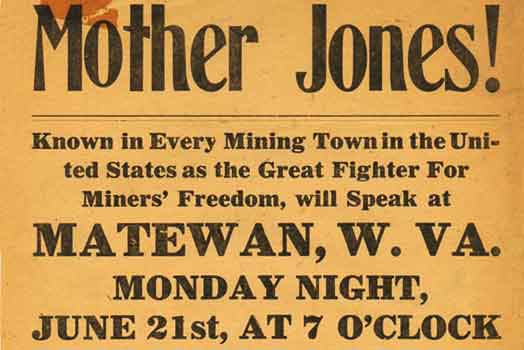

The Buried History of West Virginia’s Coal Wars

Unlike most holiday imagery, a symbol for Labor Day can be difficult for many Americans to conjure. Is it a muscled arm wielding a tool? An American flag? The dreaded hammer and sickle?

To West Virginians like Wilma Steele, the perfect symbol for Labor Day is a red paisley bandanna. This was, after all, the unifying costume of West Virginia coal miners during the largest labor uprising in American history.

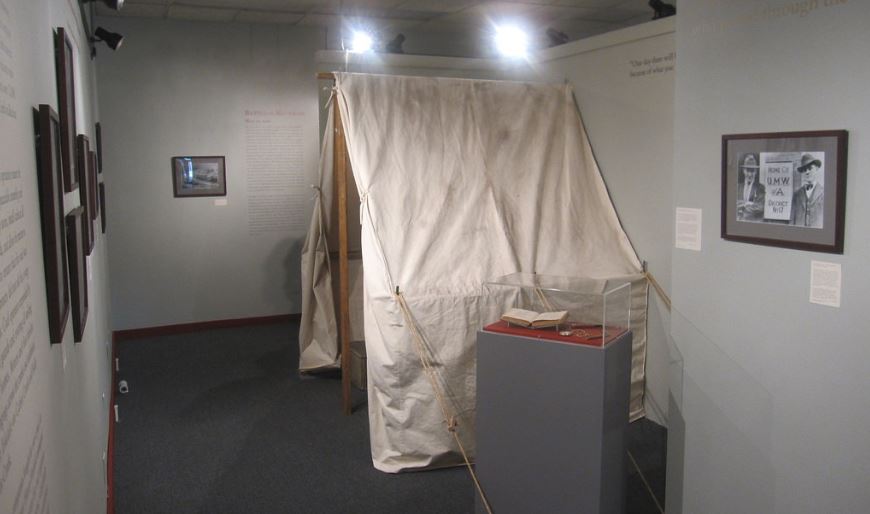

Steele is a board member and co-founder of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, a humble collection of artifacts and displays in Matewan, West Virginia. The museum is one of the only surviving testaments to the struggles of the state’s coal miners in the early 20th century – a labor story that Wilma believes more people ought to know.

Matewan sits in Hatfield-McCoy country, in the southwest corner of the state, just across the Tug Fork River from Kentucky. The town of 500 people includes a downtown district designated a National Historic Landmark for its role in the escalation of the mine wars.

At the turn of the 20th century, southern West Virginian coal miners faced uniquely squalid working circumstances. While the United Mine Workers of America had organized many of the mines in Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, mine owners in West Virginia discouraged their workers from unionizing, hiring guards from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to squash dissent and evict striking miners. West Virginian mine workers lived in company housing and bought their groceries (and mining tools) from company stores with their pay, a company currency called scrip.

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, a brassy and bold labor leader, began speaking to miners around the state in the 1890s, giving powerful calls to action laced with obscenities. According to James Green’s The Devil Is Here in These Hills, a U.S. district attorney “named her ‘the most dangerous woman in America’ because she could, by her own words and deeds, persuade hundreds of men to walk out the mines.”

And she did. The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strikes brought a year and a half of armed conflict between miners and mine guards to the Kanawha Valley southeast of Charleston in 1912. After striking for better wages, an eight-hour workday, and the right to assemble and organize – all having been afforded to their northern counterparts – miners were evicted from their houses and took to canvas tents in the hills provided by the UMWA. Mother Jones called on the workers to take up arms against the Baldwin-Felts agents, who had shot at the miners’ tents from train cars, and the workers retaliated. Miners fired on trains bringing in mine guards and strikebreakers and blew up railways with dynamite. Governor William Glasscock declared martial law and sent the National Guard to bring order to the region three times, and his successor Henry Hatfield finally established a lasting – albeit all-around unsatisfying – negotiation between mine owners and strikers.

The West Virginia mines saw relative peace during World War I, but the next eruption of violence put little Matewan on the map in 1920. After a significant rise in UMWA membership in Matewan, Baldwin-Felts agents arrived to oust union members from Stone Mountain Coal Company housing. The town mayor, Cabell Testerman, and union-sympathizing police chief, Sid Hatfield, confronted the agents near Matewan’s train station on their way out, and the ensuing shootout left 10 dead: seven agents, two miners, and mayor Testerman. No one could agree on who shot first, but the Matewan Massacre rallied UMWA members in West Virginia to boost their southern membership and begin a general strike.

Martial law was declared in Mingo County, and scores of miners were arrested under suspicion of union activity. The governor sent over 1,000 special police to Mingo, strengthening UMWA claims around the state that the county’s miners were under attack.

Meanwhile, Sid Hatfield was acquitted in the murder trial and became a hometown hero to Mingo County miners. But when Hatfield and his deputy were gunned down by Baldwin-Felts agents on August 1, 1921, the already-volatile strike became an all-out war.

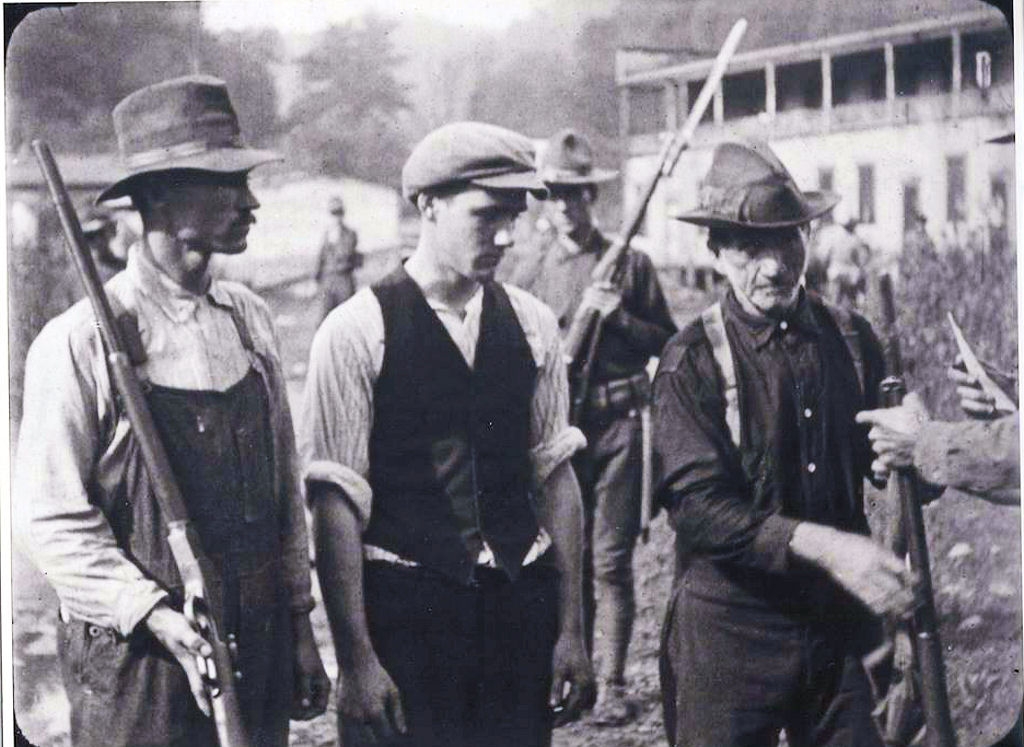

“The only way to get your rights is with a high-powered rifle,” claimed organizer and longtime miner Frank Keeney, as he gathered thousands of miners in Lens Creek in the weeks following Hatfield’s assassination. The “Redneck Army” consisted of immigrants, black miners, and generational West Virginians wearing red bandannas around their necks. The plan was to march to Mingo County to free their jailed comrades, but first the army would have to cross Logan County, where Sheriff Don Chafin had assembled the Logan Defenders, made up of thousands of local and state police as well as Baldwin-Felts agents.

The 10,000-strong Redneck Army clashed with the Logan Defenders at Blair Mountain. Chafin’s men utilized machine guns and even biplanes with homemade bombs against the miners in the five-day skirmish. Even so, only about 20 men died overall in the Battle of Blair Mountain. Two thousand federal troops broke up the fighting and dispersed the respective forces under the command of President Harding.

The leaders behind the Redneck Army, Keeney and others, were indicted for state treason, but most escaped conviction. The harshest blow was to the UMWA, whose numbers dwindled in the coming decade. It wasn’t until F.D.R.’s New Deal programs of the 1930s that the miner’s union picked up again.

The stories of Mother Jones, Frank Keeney, Sid Hatfield, and the rest of those involved in the mine wars were kept among West Virginians for generations – along with the physical remnants of the state’s difficult past.

Long before they opened the Virginia Mine Wars Museum in 2015, Wilma Steele teamed up with some other West Virginians to incorporate their heirlooms, artifacts, and local history in a way that could benefit everyone. A canary cage used by miners during the period kept the birds that would warn the workers of dangerous methane in the mines. Oil-wick cap lamps kept an open flame on a wick attached to the workers’ hats that both allowed them to see their work and also posed the severe risk of igniting explosions. Metal scrip pieces could buy provisions at the company store while only going for about 75 percent of their worth for cash. Rusted remnants of an 1873 Remington carbine and some bullet casings recovered from Blair Mountain illustrate well the tools of a miner who has put down his pickaxe.

Kimberly McCoy, a museum guide who grew up in Matewan, shows guests the bulletholes on the back of the museum’s brick building from the Matewan Massacre while explaining how folks in town always felt about “Smilin” Sid Hatfield. “Children around here are generational coal-mining children. They need to know how their grandparents and great-grandparents struggled for them to be able to choose a profession today instead of going into the coal mines at 15 years old,” she says.

The museum believes the story of the mine wars should be taught to all West Virginian schoolchildren. That’s why, this year, they’ve created curricula for fourth-, fifth-, eighth-, and eleventh-grade students to learn about the decades-long struggle of the state’s miners. Given the complicated and contradicting historical accounts of the events, students are encouraged to read primary sources and think critically about the working conditions of miners and child laborers and to take part in role-play, considering how they would’ve acted 100 years ago.

Keeping the history of the mine wars alive for West Virginians has been a battle of its own. In 2011, Wilma Steele marched on Blair Mountain with hundreds of others in the group Appalachia Rising to call for an end to mountaintop removal mining and declare the mountain a protected historic site. The place where 10,000 “rednecks” took up arms against big coal was, coincidentally, at risk of being mined itself by several companies who claimed surface mining permits on Blair Mountain.

Mountaintop removal mining began in the 1960s, but it became more prevalent in Appalachia in the ’90s. The widely-criticized form of coal mining is executed by blasting off mountaintops with explosives to reach coal seams underneath. According to the EPA, mountaintop mining poses significant risks of contaminating nearby streams and rivers. Many Appalachians, like Steele, have long opposed the practice because of the detriment on nearby communities: deforestation, loud explosions, and dust accompany the mountaintop mining process. The landscape is often spoiled, and the number of jobs created in the region cannot begin to reconcile with the damage.

Blair Mountain Battlefield was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, then de-listed after a few months due to objections from the coal companies with permits in the area. Just this June, the site was added back to the list after years of legal battles and advocacy from groups like The Sierra Club and Friends of Blair Mountain.

The spirit of the Redneck Army was also present in the state this past February when West Virginia public school teachers protested in Charleston during a nine-day strike for higher wages while wearing red shirts and – for some – red bandannas. The demonstration set off a chain of teacher strikes and marches in Oklahoma, Arizona, and Kentucky.

Wilma Steele believes in the historical significance of the red bandanna, and that’s why she shares them with activists everywhere she goes. “The paisley pattern on a bandanna shows organic designs and geometric designs in balance,” she says, “the figures in paisley could look like a tear, or a drop of blood, or they could come together to form a heart.” Her husband Terry was a 4th-generation coal miner, and he belongs to UMWA 1440 in Matewan. The building housing the union presides over the historic town, and it’s a short walk from where Sid Hatfield confronted agents from Baldwin-Felts. Kimberly McCoy comes from generations of miners too. The historic labor struggles of West Virginians might be difficult for outsiders to grasp, but – like the bulletholes in the brick of the museum’s exterior – the implications of the mine wars are imprinted on the people. “I know the history,” McCoy says, “it’s my history.” When asked what the stories of Sit Hatfield and Frank Keeney can mean for others, she says, “We are the story of the working class. We’re proud of rednecks here.”

Sources and further reading:

The Devil Is Here in These Hills by James Green

Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922 by David Corbin

http://www.wvculture.org/hiStory/journal_wvh/wvh50-1.html

https://www.pbs.org/video/american-experience-mine-wars/

Eleven Jewish Korean Vets

“You come from a family of addicts,” her mother warns her. Amy’s been slipping away to the alley behind their Chicago apartment for many more purposes than her mother knows. But her mother has just washed Amy’s favorite jacket, and behold! (oy!) found a soggy remnant of a cigarette stub in the pocket.

Amy the adult will hate cigarette smoking, although she will not be averse to inhaling a little weed now and again. As an 8-year-old, however, her main concern is simply for the safety of her secret stash of Camels hidden under a pile of abandoned Barbie dolls in her closet, cigarettes stolen from E.J. Korvettes, a mere three-block walk from most points of her limited universe.

Despite the confines of her narrow existence, Amy manages to do as she wishes; the secretness of it all, a thing she loves. She is an impetuous, strong-minded child who steals candy, cigarettes, pen knives, small toys — whatever she can easily slip inside her pockets and later stash in the several hiding places she’s discovered around their apartment and in the alley. She also loves to toss basketballs in the alley with some very adult butch women, a thing she will always love to do.

Now watching her mother’s face gradually go from bright red to pink, she understands her mother’s anger is already fading. Her mother is an intelligent woman with the long, slender fingers of a musician and a razor-sharp tongue, though her anger tends to flicker out nearly as fast as it flares; a woman who is as easily distracted by a bug on the wall as a cool fall breeze, or a memory that floats behind her eyes and lands squarely on the forefront of her mind.

Amy calls her parents Mitzi and Morris. Jewel, her sister, she calls Butt Face or sometimes just Butt.

At 13, Jewel weighs more than her mother, Mitzi. More than her father, Morris. She was named Jewel after Morris’ mother, a fact she will never forgive. In the dark shadows of their bedroom, Jewel has confided to Amy she would give up anything, anything at all except maybe food, to have a name like Susan or Linda, or even Babs.

Their father Morris’ addictions are Peppermint Schnapps, baseball, and sleeping on the couch in daylight hours. He works nights driving a cab and these are the only hours on the couch he has. Amy ignores him, ignores everything that doesn’t concern her, which of course is everyone and everything — perhaps the ‘things’ most of all. All the heavy furniture, doilies, old gray-and-white family pictures, silver candle sticks, hand-dipped Shabbat candles, buffet overflowing with Passover dishes, silver platters, stupid ceramic figurines — far too many to count — things which seem to Amy to be overtaking the house, crowding her out.

She will grow from a skinny, 8-year-old tomboy into a small-framed, femme woman, which to a 20-something Amy will mean she fusses with her hair and cares what she wears. Later, her femme identity will acquire more nuances — a certain fluid walk, talk, at times a stance with hands in pockets, as if fearful of what her hands might do if free. She will be attracted to women but there will also be two or three men in her life. She will consider herself a primarily woman-identified woman and (although not strictly) a monogamous person. When she is with women, she won’t think of men at all; then again, there will be a few men she sometimes thinks about, mainly Richard Gere types, i.e., handsome, sexy, and emotionally distant. This might apply to anyone to whom she will be attracted.

Amy the adult will be much like Amy the child, who is attracted to those things not easily within her reach. At eight, she has been shoplifting for over a year and is now quite skillful at it. And there are many stores within walking distance from her school in which to apply her natural aptitude. Amy goes to a public school close to a candy store, drug store, the A&P, and of course E.J. Korvettes.

Amy has always loved that store, maybe even more than Mitzi, and while Mitzi shops for Playtex bras on sale and discount shirts for the family, Amy lifts a set of press-on nails and a Swiss army knife look-alike and slips them into the pockets of her favorite jacket. With elastic around the bottom that hugs her slim hips, it sports a zipper instead of buttons and has two deep pockets both inside and outside. It is 100 percent a boy’s jacket, all the more reason it’s Amy’s favorite, an unconscious but wise choice of Mitzi’s, pulled from a Korvettes sale bin.

Heading home from their shopping trip, the air is brisk and the streets are filled with the woody smell of burnt leaves. Autumn is Amy’s favorite season. She is happy to be skipping through the fallen leaves alongside Mitzi, who swings her arms filled with bags of discounts; she is lighthearted and even cheerful, and then Mitzi announces Amy needs to start Hebrew school so when she reaches 13 she can be bas mitzvahed.

Amy couldn’t care less about being bas mitzvahed. She could care less about religion and even less about being Jewish, which in her 8-year-old opinion has some pretty stupid traditions. She’s been grounded more than once for putting meat silverware into the dairy drawer. She’s never tasted bacon or been allowed inside a McDonald’s, nor has she ever awoken to Hanukkah presents lying in sparkling splendor under a Christmas tree. Why does she need to be bas mitzvahed if she never intends to be Jewish? “Why can’t we be Catholic?” she asks Mitzi.

“You think that’s better? You think you can throw away your ancestry so easily? Well guess what? Guess where E.J. Korvettes gets its name? Take a guess.” Mitzi doesn’t wait for an answer. “Eleven Jewish Korean Vets,” she says, and smiles smugly.

“So?” Amy refuses to show it, but she is surprised. Surprised all the way down to the toes wiggling inside her scuffed-white Keds.

“So you love Korvettes,” says Mitzi. “And it’s Jewish.”

She will never go there again, she sulks, but her fingers are crossed. She has loved that store for as long as she can remember. Longer it seems to her than she’s loved Mitzi.

She would also rather eat bugs, eat dirt, do almost anything than go to Hebrew school. She bounces on the sidewalk, stamping the crisp leaves underfoot as she deftly skips over the cracks, and makes her plans. She’ll make jokes in class and not do her homework. She’ll go behind the temple and smoke Camels and get expelled.

By the time she has thought of all the plans she is able, they are home. Amy heads for the bedroom and plops down on her bed. She is thankfully alone, her sister somewhere else, likely stuffing her face. Her eyes close and behind her lids, she silently greets her friends, Sheri and Diane. She greets them silently because of course they have no need to speak — each knows what the other is thinking — and moments later the three do what they always do, which is to hold their thin arms straight out in front of them and take off out of Amy’s window and over her house with its rules about this and its rules about that. They easily navigate themselves above the tallest buildings, houses, parks and within minutes traverse the great expanse of Lake Michigan to the opposite shore where their hideout lies — a cool, craggy, magical cave, filled with Amy’s stolen loot: three Swiss Army knives; a small screwdriver set; a handheld, battery-run tape player; a collection of the Shirelles (“Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “Soldier Boy,” and of course, “Tonight’s the Night”); two packs of unfiltered Camels; a bag of richly colored glass and quartz marbles; and a cache of Hershey bars. A fine haul, they agree. They listen to the Shirelles while they smoke their Camels and fly in circles around the cave, joyful and buzzed, their gangly bodies free, replete with delicious grace.

Her imaginary adventures with Sheri and Diane will fade with time, almost certainly by the time she reaches the seventh grade, the beginning of her social anxieties. Looking back, Amy the adult will long to recapture the exhilaration of her youthful imagination. She will remember how her flying friends helped her endure a year of Hebrew school, and how she got out of going back for another year of Hebrew school by purposely flunking out, her (and their) best idea yet. She will also remember the lifting of items and hiding them in the alley behind their apartment building, events that will seem to be linked together in her mind as if they have melded into one. Other details, like the now defunct Korvettes department store she so adored and yet wished to disavow, will fade away, a fuzzy memory floating underneath the surface of her mind nearly full with the urgency of everyday things.

Her adult mind will work in a diffused, sometimes incoherent manner, leaving her to wonder exactly what those daily urgencies are. Other times, memories of the past will push up to the edges of her mind and present themselves with great clarity. Memories of being a wild little kid with a flat chest and long, stick-like legs, her childhood mind on the simplest things: not getting caught doing the things she loved, not getting lectured on the family’s addictions, and not having to be bas mitzvahed. Big deals to a kid, her adult self will suppose.

Her sister, Jewel, will go through the whole bas mitzvah thing, and in her 20s become a fearsome coke head. In her 30s, she will voluntarily enter rehab, and marry for the first time at age 40 to a divorced man who pays most of his commissions to child support for his three semi-grown kids.

But Amy the child has too many of her own devils to deal with to pay much attention to Jewel’s current addiction, which of course at 13 is food.

With no small amount of irony (which she will appreciate many years later), it is at Amy’s beloved, bedeviled Korvettes where she gets caught red-handed. In one deep pocket of her fall jacket is a twenty-dollar bill, stolen from her mother’s purse, and in another, a thimble and a pair of sewing shears lifted from Notions. Moving onto Records, she has just placed her hand on a tape by The Supremes, when a tall, prickly-faced boy suddenly grabs her by the jacket sleeve and drags her into the aisle.

“You’re dead meat. I gotta take you to the office now. You know what that means?”

Amy could guess. A picture of fat Butt Face Jewel laughing at her, of Morris and Mitzi yelling at her and maybe grounding her for life, flashes through her brain. She tries thinking of something to say, anything at all, only to discover her brain has stopped working and is trembling like the rest of her, making her tremble all the more.

The boy can see her skinny legs shaking in her pedal pushers. By God, she is one of the scrawniest human beings he’s ever seen. This is his first job, his first promotion from cashier to security one week ago today, and he takes it all very seriously. Serious enough to grab an 8-year-old by the britches and haul her skinny ass to the Security Room. If need be, he’ll carry her there.

Later in life, when her girlfriend stuns her with her sexual prowess, Amy will be shocked to realize she can still be surprised. She will have become a woman who considers herself a person no longer able to be surprised by much in life, who can count on one hand the times she was ever surprised. The day she got busted in the Record department, the day she found out she could hate something she also loved, the first time she made love to a woman and discovered there was no turning back. She will be able to add to her list this woman who gives her an orgasm so fierce her legs shake afterwards for hours. A little like her 8-year-old legs now dangling from a chair in the Security Room as she waits for Mitzi to arrive.

“There are two things I can’t stand: a sneak and a thief,” says Mitzi. Heading home, Amy stepping on the cracks (break your mother’s back), Mitzi so angry she is nearly running. She tosses out question after question. “Don’t we give you all you need? What am I going to do with you? What? How am I going to tell your father? Where did you get twenty dollars anyway? And why would you steal if you could buy it?” Amy doesn’t know, doesn’t know, doesn’t know. Perhaps she will never know.

Not even when she turns 30 and goes into a year of costly therapy will she receive an answer to these questions. Perhaps if the therapist were to tell her stealing was an act of self-love, a way of giving yourself something you want for the pure pleasure of taking it, she might believe it. But the therapist will be a pretty Jewish woman with intelligent brown eyes and big hoop earrings who will invite her out for a drink after their fifth session. A woman more interested in getting into her pants than her brain. Not that Amy won’t be aware.

Amy will be aware of many things during her short year of therapy. Among other painful memories, she will recall she had few real friends before college and ponder the reasons. She may have been a skinny teenager, but if her lovers were any judge, she was definitely not ugly. And she was sometimes entertaining, wasn’t she? Or adventurous at least. Why was it so hard to make friends?

Was she too eager? she will wonder, or too standoffish? Did she reek of desperation, or don’t-come-near-me? High school was the worst of all. She was a good student when she put her mind to it, which was not often. And there was that confusion about friendships and loyalties, and about boys, and girls who didn’t like her clothes, or her sense of humor, or her boastful stories of getting high smoking weed behind the gym during football games with her boyfriend, whomever that was, depending on the day, the month, the year. At least the boys liked her well enough.

In primary school, she will tell the therapist, she had yet to fall in love, although she certainly had her share of crushes — with a tough boy in the seventh grade who bragged he stole cars, with Sally Metzger, a girl in her third-grade class who already had budding, young breasts, and of course, with all of the butch women with whom she played basketball.

One of the butch women in particular, she will remember, was maybe 15 or 16, a lot younger than the rest. She was a tall young woman who gelled her barber-trimmed jet-black hair up into short, sharp spikes. Amy will recall how she was unable to look away from her beautiful milky skin, intense, dark eyes, and those powerfully built arms of hers, so easily able to smack the ball out of Amy’s tiny child hands that were working so hard on mastering the fine points of a defensive slide. She often dreamt of those arms encircling her, pulling her up against the woman’s strong, lean body … Ah, Tara, she will think, her nipples suddenly standing at attention.

Then in her freshman year at college, she will admit to the therapist, she had fallen in love with her roommate’s boyfriend. She was able to set all thoughts of Tara aside, and in fact all thoughts of women were put into a box and locked in a drawer as the intensity of this boy’s emerald eyes sent chills down her spine.

How confusing life is, Amy will think at 8, and then 18, and then one day realize she had experienced herself throughout the decades without noting or observing them, until here she was, a woman in therapy, a woman who perhaps had yet to accept who she was — though even that wasn’t clear — but when it came right down to it, age didn’t seem to matter at all. You could be any age and still be confused.

Then other days, she will see things quite clearly. On these days she will see, for instance, the therapist’s ethics really do stink. But Amy’s attraction to her will be as powerful and mystifying to her as the itch to steal, an itch that thus far as an adult, she will have scratched only once or twice (when the mood and an irresistible occasion coincided), leaving her bewildered and frustrated that her principles aren’t stronger.

The therapist will want to dig into Amy’s past as a way to explain where she is today (which is where? Still anxious, still moody, not exactly happy with herself?). But Amy will spend most of her time in therapy avoiding the subject. Sick of the sound of her own whiny voice, she will be unable to think of anything about her family that could possibly be relevant.

“Let me decide what’s relevant,” the therapist will tell her.

Towards the end of her time in therapy, Amy will come to the conclusion something is sorely missing. Longing for something she can’t quite place, she will eventually find it in Neiman Marcus.

She will catch a young woman’s eye as the woman picks up a T-shirt and begins to walk towards the dressing room. The woman’s furtive glances, the way she holds herself, as if ready to run — Amy will know instinctively the woman has no intention of buying the shirt. She will wait until, sure enough, the woman slips the thin T-shirt easily into a deep pocket of her jacket and soon after exits the store, Amy a few steps behind her. It will become the beginning of their relationship, a story Amy will tell to the therapist, if for no other reason than to watch her discomfort, which Amy will feel the therapist richly deserves.

The therapist will take her to the opera and to plays — always tragedies — and afterwards, to some hip after-theater restaurant where the therapist will seem to always run into one of her self-important friends. But the sex is phenomenal, and Amy will be loath to give it up, perhaps because she and new girlfriend are not yet having sex — the new girlfriend’s idea. She’s old-fashioned, or so she says. Actually it will be because she prefers not to compete. The girlfriend will be a non-confrontational pacifist through and through, from her clumsy square-toed shoes to her flowing, ash-blonde ponytail. And anyway, the girlfriend will know, a little wanting can go a long way.

Amy will spend most of her time with the girlfriend in the mall shoplifting, an activity akin to the thrill of the hunt. The chase and kill will be what it’s all about for them both. For Amy, it will also call up her days dribbling a basketball across the alley, dodging Tara and the onslaught of her large butch friends ready and willing to steal it away from her small, nimble hands. To Amy and the girlfriend, the ‘chase and the kill’ will not be mere code words, but as exhilarating and satisfying as the most outstanding sex between them might be.

Then while in Lord & Taylor one afternoon, the girlfriend will be playing the chaser asking to see the earrings behind the locked case as Amy meanwhile expertly kills several pair of gold earrings from the counter and slips them into her pocket. It will be a neat little job, one they are quite satisfied with, but as they exit the store, an inner alarm will suddenly go off inside the girlfriend’s head.

“Toss ’em,” the girlfriend will whisper fiercely, and Amy will ditch the earrings as fast as she can as two security guards approach.

One of the security guards will be a hefty woman with small black hairs poking out of a mole on her cheek. “Up against the wall,” the guard will growl with her tough-as-gristle voice.

As the woman pats her down, Amy will shudder inside. This will be no small pocked-faced boy grabbing her by the scruff of her collar.

The girlfriend will admit to Amy she was plenty scared, but also excited. Amy will understand. It will be this sort of moment that she has dreaded and thrilled to most of her life.

“But mostly dread, you know?”

The girlfriend will know. It’s the reason, she will tell Amy, that she wears her hair in a ponytail: to affect a look of innocence. “But not foolproof, eh?” she will smile. Her smile is a bit sideways, Amy will notice. Very sexy.

Amy will soon stop dating her therapist and start dating the girlfriend exclusively. But for now, Amy will be happy with things as they are. And at the moment they are: the therapist, the girlfriend, and Amy sitting on Amy’s couch getting stoned, listening to Melissa Etheridge burn down the house.

The cannabis is prime, and Amy’s head will already have begun to feel like it’s underwater, when she will think maybe she should quit the therapist once and for all, an idea that will feel like a grand revelation. That, or perhaps there is potential here for a threesome.

The therapist will be under the impression it is simply Amy’s addictive nature which prevents her from leaving her. In fact, she will be counting on it.

Amy will think, it’s like that old joke about the woman who goes to her psychiatrist, who tells her, “My dear, you’ve got a chicken on your head.”

“Have you heard this one?” she will ask them both.

The therapist will shrug, affecting a look of mild boredom, for surely it will not have been her idea that the girlfriend join them.

The girlfriend, on the other hand, will smile her sexy sideways smile. “Hit me, babe,” she will say, the girlfriend’s uncharacteristic use of the word ‘babe’ sending a chill down Amy’s spine.

At that moment, Amy will see that in a rough sort of way, the girlfriend is quite attractive; feature for feature, maybe even more attractive than the therapist. The girlfriend is what the therapist calls ‘soft butch,’ a category in which the therapist lumps all the quiet or non-aggressive types who aren’t femmes. But Amy won’t care what the therapist calls her, she’s got two girlfriends now (if she counts the therapist), and a year ago she had none.

“So the woman says to the psychiatrist, ‘Yes, I know there’s a chicken on my head.’

‘My dear, why not simply remove it?’ the psychiatrist asks.

‘Well I would,’ says the woman,’” (and here, Amy will pause for affect) “‘but I need the eggs.’”

The therapist will arch one humorless, crescent-shaped brow, suggesting volumes — irony, smugness, disdain.

While the girlfriend smiles. “Love it!” she will say, and wink at Amy, a powerful suggestion to Amy’s roiling mind that will conjure the twinkling lights of Christmas.

The girlfriend will soon walk into a barbershop and watch as the barber cuts off her ponytail in two quick snips. “Ah, just as well,” the girlfriend will sigh, watching mounds of ash-blonde hair cascade to the floor. She’s pressed her luck long enough.