50 Years Ago: Arthur Ashe Makes Tennis History at the First U.S. Open

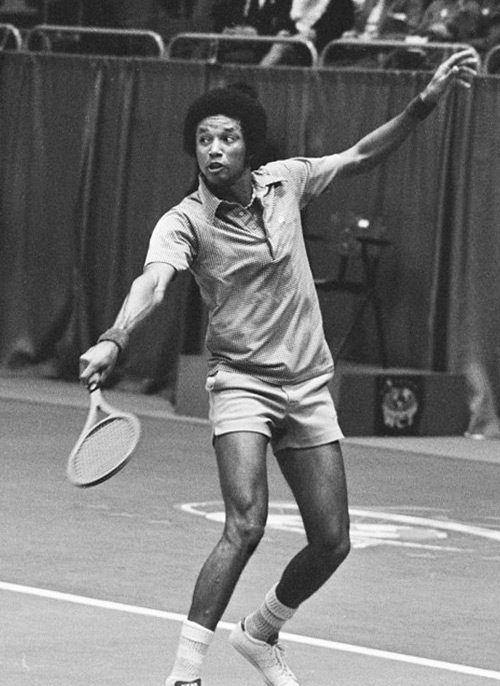

The course of sports history changed 50 years ago when the Open Era of tennis arrived. What had been the U.S. National Championships since 1881 transformed into the U.S. Open, a tournament that allowed the amateurs of the sport to face off against the professionals. In that first Open, 63 women and 96 men competed, including one of the biggest names of all time, Arthur Ashe.

That first Open didn’t look much like the Open of today. It was held at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, New York, and played on grass (it would switch to hard clay in 1975 before settling on the current hard court DecoTurf in 1978). There was also no Mixed Doubles category; the four championships on the line were men’s singles, women’s singles, men’s doubles, and women’s doubles.

The finals line-ups read like a roll call of legends. Women’s doubles featured the team of Brazilian Maria Bueno (lifetime winner of 19 Grand Slam titles and the first South American woman to win Wimbledon) and Australian Margaret Court (winner of more majors than any other tennis player and the first women’s Grand Slam winner), defeating Americans Rosemary Casals (90-tournament winner and activist for female athletes) and Billie Jean King (all-time legend and recipient of Presidential Medal of Freedom, among other accolades). In men’s doubles, the American duo of Bob Lutz and Stan Smith (Davis Cup teammates who had tremendous individual successes but won 37 titles together), won against Ashe and Andrés Gimeno, a Spanish player who would go on to win the 1972 French Open. In singles action, King lost to Virginia Wade, still the only British woman to win a Grand Slam title. And on the men’s side, Ashe beat the heavy-hitting Tom Okker, a Dutch player who would spend the remainder of 1968 and the next six years in the top ten rankings.

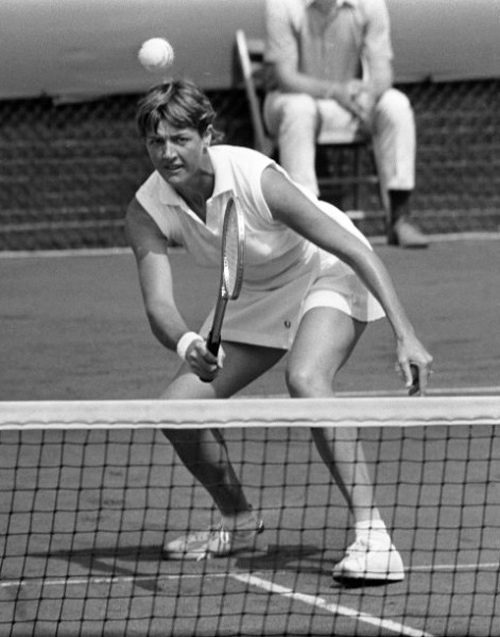

Arthur Ashe wins the first U.S. Open.

While this was obviously a case of legends of display, the biggest story was probably Ashe, in part because his story was so improbable. Born the son of a handyman and his wife in Richmond, Virginia, Ashe lost his mother when he was seven. Ashe lived with his father and brother in caretaker’s quarters in Brookfield Park, a blacks-only park where he learned to play the game. Fortunate enough to find a string of mentors who recognized his talent and helped him navigate school systems that wouldn’t allow him to compete on the basis of race, Ashe eventually won the National Junior Indoor title and a scholarship to UCLA in 1963. He enrolled in ROTC, was recruited for the Davis Cup team, and in 1965, won the NCAA singles and doubles titles (with Ian Crookenden).

By 1968, Ashe would also win the Unites States Amateur Championships before heading to the U.S. Open. By all rights, Ashe shouldn’t have been in the Open, due to his military obligation stemming from his ROTC status; remarkably, his brother Johnnie was allowed to serve in his place so that Ashe could compete in the tournament. When he eventually beat Okker, Ashe became the first black man to win the new Open and the National Championships that had preceded it. It also made him the only person to win the USAC and the Open in the same year. However, due to a rule of the time that demanded that Ashe stay an amateur in order to compete on the Davis Cup, he had to decline the U.S. Open prize money. The $14,000 winnings were given to Okker.

Ashe went on to have an incredible career, winning 66 singles titles and 18 doubles. He is the only black man to win the U.S. Open, Wimbledon, and the Australian Open. He used his celebrity for education and activism, founding children’s leagues and events and protesting South African apartheid. Unfortunately, heart problems that were likely inherited from his mother led to a pair of bypass operations through which he contracted HIV. Going public with his disease in 1992, he became an advocate for HIV and AIDS education, even addressing the United Nations. He died from AIDS-related pneumonia on February 6, 1993.

Today, the main court of the four stadiums at the USTA National Tennis Center, the Open’s home since 1978, bears Arthur Ashe’s name. Since 1987, the Open has been the final of the four Grand Slam tournaments in the calendar year, following the Australian, the French, and Wimbledon. The 2018 U.S. Open kicks off today, August 27, and runs until September 9.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Relapse Prevention, Part I

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Batter Up

Weight management is unlike many disciplines in the medical field. When a surgeon operates to remove a gallbladder, the operation is almost always successful. When you take an antibiotic for an infection, you usually get better. When you wear a cast, the bone generally heals. Weight management is more like baseball than medicine. If you’re a good major league hitting coach, your players may get a base hit three out of ten times. Your hitter may only hit a home run once every 20-30 at bats. Like hitting a 90-mile per hour fastball, weight management is hard. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a program of studies that includes ongoing assessment of weight. One study from data including over 14,000 people sheds light on how difficult weight management can be.

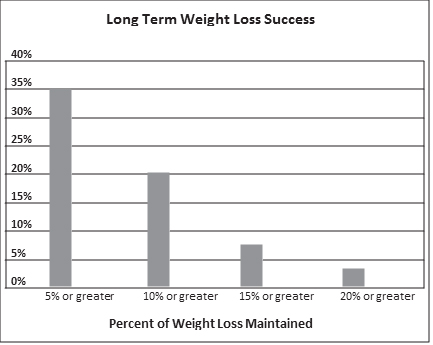

The figure below shows the percentages of people able to lose weight and keep it off for at least one year. As you can see, losing and keeping off 5 percent of weight (a 12-pound weight loss if you weigh 240 pounds) happens for just over one-third of people. This is sort of like hitting singles. The probability of losing and keeping off 20 percent of your body weight (48 pounds if you weigh 240 pounds) is similar to the average professional baseball player’s chances of hitting a homerun at any given at bat — 4.4 percent, or 1 out of 23.

One big problem with weight management is that most of us want to hit a home run; we forget that singles matter. Additional research tells us that a 5 to 10 percent weight loss improves health, helps prevent diseases like type 2 diabetes, and improves other health conditions such as high blood pressure.

It’s important to point out that the NHANES data don’t differentiate between people who had bariatric surgery and those who lost weight without it. However, during the time of the study only about one out of every 2500 people had bariatric surgery, suggesting almost all these data relate to people who chose not to have surgery.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery is much greater than this, but those patients also risk short and long-term complications. In addition, most bariatric surgery procedures aren’t appropriate for people who have less than 75 pounds of excess weight (gastric banding procedures are exceptions and can be performed for people with various medical conditions who are 30 to 40 pounds or more overweight).

The following section on relapse prevention isn’t about hitting home runs or being happy with singles. Instead, I want to explore your approach to hitting with questions such as these:

- Can you keep your head in the game even after consecutive strikeouts or making an error in the field? That is, how do you handle holiday mishaps without falling back into old habits for an extended period of time?

- What is your approach to vacations, eating chocolate, or getting back on track after a binge?

- Do you continue to exercise even when you’re struggling with your eating?

You may hit homeruns with the amount of weight you lose — or you may hit singles. The important part is staying in the game without giving up, and continuing to focus on your health while balancing other parts of your life.

As previously discussed, bariatric surgery is a bigger bat, so to speak, and only certain folks should use it. Surgery is not better in all cases, and many of you will be using a smaller bat. However, all great baseball players have common characteristics to their swing, no matter what size bat they use. Along those same lines, we need certain attributes for successful weight management.

Check Your Weight, AND Keep Your Eye on Behavior

Research shows that frequent weighing helps prevent relapse. People who keep weight off tend to step on the scale at least weekly. By comparison, those who are unsuccessful with their weight often view the scale as a tripwire that punishes them if they take a step in the wrong direction. They weigh when they know they’re following a safe path, but avoid the scale when they veer a little off course.

In previous posts we covered ways to adjust our thinking in order to view the scale as a dependable friend giving us positive feedback to help correct our course. I encourage each client to use these skills and eventually reach a point of weighing regularly, especially when the body reaches a natural plateau after weight loss.

Even though regular weighing is extremely helpful to prevent relapse, weight doesn’t tell the whole story about progress. For example, a 40-pound weight loss can represent different things for different people, based on starting weight and weight-loss treatment. If a 400-pound man has gastric bypass surgery, loses 40 pounds, and then has a six-month weight plateau, he has probably relapsed. His lack of expected weight loss tells us there are problems. He probably returned to unhealthy eating patterns that might include high-fat snacks, sweet tea, or fast food.

Let’s compare this surgery patient to a woman who is less overweight, lost 40 pounds, and kept it off for three years without bariatric surgery. In her case, the weight plateau is probably a sign that she’s following a healthy eating plan and regular physical activity — even if she’s still 30 pounds overweight by medical definition. Her metabolism and appetite have adjusted to her new weight, so the plateau isn’t necessarily a sign of unhealthy habits.

As the previous figure suggests, most people who lose weight are still considered overweight or obese by body mass index (BMI), a simple weight to height calculation. It’s crucial for you to remember that maintaining weight loss has many health benefits even if the charts still indicate you’re overweight. Just because your weight plateaus at a number higher than you desire (or a BMI chart recommends) doesn’t mean you’re doing something wrong or you relapsed into old behavior. The only way to truly evaluate how you’re doing is to look at what you’re doing.

We can rarely define weight-related relapse with one behavior, so you need to look at many daily decisions when examining your lifestyle.

Comparing eating behavior relapse to drug abuse gives us another way to look at this concept. With drug use, an addicted person relapses when he returns to using drugs. It’s usually black or white — he’s either clean or relapsed. Although the addict often starts behaving in ways that predict relapse, we define relapse with specific behavior: He’s using again.

Weight management is different because the behaviors aren’t black and white. Eating cheesecake can be part of an overall healthy eating plan — or it may be one of many signals that someone has relapsed into old patterns. For successful long-term weight loss, you need to maintain a variety of healthy practices such as regular exercise, portion control, balance between food groups, and limiting calorie-dense foods.

Frequent weighing is a simple and helpful way to create a centerpiece for your relapse prevention plan. But remember, we weigh ourselves to become more aware of our behavior. And behavior should be the focus of our plan to get back on track when we struggle.

Identify and Plan for High-Risk Situations

If you have an important work-related meeting at eight o’clock in the morning and a snowstorm is supposed to hit your area at 4:00 a.m., what would you do? If you’re planning a long car trip, how do you prepare? What if your child complains of a stomachache before bed? Experienced snowy weather residents, veteran travelers, and wise parents understand each of these situations is high-risk for something undesirable to happen. Being on time for a meeting may require getting up early to shovel the driveway and allow for a longer commute. An experienced traveler packs in advance and has the car serviced before a long trip. When a child complains of stomach problems before bedtime, parents soon learn to prepare for a possible upchuck in the middle of the night. (My mother sent us to bed with “puke sacks,” and my wife’s family used bowls, which makes me leery of eating soup when visiting them.)

My point is, most of us know how to identify, plan, and prepare for high-risk situations in our lives. We know what works and what doesn’t. Based on experience, we change our approach over time.

When it comes to exercising and eating the right foods, high risk situations are all around us. What events jeopardize your weight management goals? Weekends, vacations, holidays, celebrations, stress, and any life transition can lead to lapses and even full-blown relapses. Think about the last time you lost weight and then began regaining it. What was going on? If similar things happened again, how could you prepare beforehand and how could you handle things differently?

Some high-risk situations are small, day-to-day events that throw us off course. Matt told me he had an issue with overeating cashews at work. He always kept a can of nuts in his desk drawer in case he worked late or missed lunch. But during normal work hours when he did have lunch, the cashews presented a problem. When things got hectic or he felt a bit hungry he’d help himself to “just one handful.” That small snack turned into mindlessly picking at cashews all afternoon until the entire can was empty. He could keep other foods at his desk without a problem, just not cashews. He said cashews weren’t a problem at home. But the combination of his work environment, plus cashews, created a perfect storm for Matt.

Other people may be overcome by shopping when hungry, having homemade cookies at home during a stressful time, driving with snack food in the passenger seat, and a dozen other scenarios that can be avoided by planning ahead.

Other high-risk situations are unavoidable. Only a hermit could totally avoid social events that challenge healthy eating. Still, we need to anticipate problems whenever possible and have a plan to stay on track. Every stressful event you prepare for is helping you develop skills to handle future situations, even the toughest ones. The longer you practice those coping behaviors and the more natural they feel, the less likely you are to fall apart when your life changes.

50 Years Ago: The Beatles Release Two Classics on One Single

One song aimed to comfort a young boy dealing with turbulence in his family life. The other song cautioned against the use of violence in social change, yet somehow managed to anger both ends of the political spectrum. The 45 single they came on hit number one in 15 countries and ended 1968 as the number one release of the year in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and the United States. The songs are “Hey Jude” and “Revolution,” and The Beatles released them 50 years ago on August 26th.

The seeds for “Hey Jude” were planted in May of 1968 when John Lennon split with his wife of six years, Cynthia, after beginning his affair with artist Yoko Ono. In June, Paul McCartney went to visit his bandmate’s soon-to-be ex-wife and their son, Julian. On the drive, a song occurred to McCartney that he called “Hey Jules.” It was meant to help make the separation easier on the young boy. Soon after, McCartney changed “Jules” to “Jude,” as he thought that latter was easier to sing and sounded better.

At the same time, Lennon was dealing with his own feelings and his increasing political consciousness. Vietnam War protests in the United States, protests against the communist government in Poland, and the May 1968 campus uprisings in France roiled together in a stew of news coverage that fed Lennon’s interest in expressing his own anti-war sentiments in song. As related in The Beatles Anthology book released in 2000, which collected interviews with the band, Lennon said, “I thought it was about time we spoke about it [revolution], the same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnamese war.”

Lennon was also deeply influenced by what he and the rest of the band had experienced with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi earlier in the year. The Maharishi introduced Transcendental Meditation to the West and became the spiritual guide for the band in a period where they publicly rejected drugs in favor of their study of TM. In a pair of stories from 1968 by Lewis H. Lapham, The Saturday Evening Post documented the band’s trip to India along with fellow musicians Mike Love of The Beach Boys and Donovan. Lapham wrote, “Lennon referred me both to their photographs and to their records as diaries of their developing consciousness. In the recent photographs, he said, he hoped people might notice “something going on behind the eyes other than guitar boogie.”

The time in India proved to be a wellspring of creativity for the band. Ringo Starr finished his first tune as a songwriter, and the incredibly prolific Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison would write a total of 18 songs used on The Beatles, aka The White Album and two for the later Abbey Road. During the trip, the band would become disillusioned with the Maharishi over what was perceived to be self-interest and alleged impropriety with another famous student, Mia Farrow, though the group softened their split with him over time. Harrison later went so far as to publicly apologize for the way that The Beatles treated the Maharishi at the time.

After their time in India, the band returned to the studio in England in May. The recordings of “Hey Jude” and “Revolution” took place from July 9 to July 13 for “Revolution” and July 31 to August 1 for “Hey Jude.” As usual, George Martin sat in the producer’s chair. The version of “Revolution” that backed “Hey Jude” was actually the third version of the song recorded. The first version is the slower, more bluesy take that kicks off Side four on the double-album The Beatles, aka The White Album. The second, experimental version, named “Revolution 9,” is the next-to-last song on that side. Lennon wanted the first “Revolution” to be the single, but McCartney and George Harrison disagreed; McCartney wasn’t sure about the political reception, and both he and Harrison had misgivings about the slower pace.

The compromise became the third, and arguably (perhaps also inarguably) most recognizable, version. The Amplifier/Boss Talk column at the Roland musical equipment company website broke down the recording technique used to achieve the legendary, distorted fuzz-tone guitar that opens the record. They reported that, “According to Geoff Emerick (the studio engineer for that session), he had John Lennon and George Harrison running their guitars directly into the mixing desk. The guitar tone is a result of one channel on the mixing desk being run into another. Both of these channels were driven well beyond their normal operating capacity. Bad news for the desk (it could have overheated and caused permanent damage), good news for guitar tone history!”

The official promotional film of “Revolution” by The Beatles.

Though the band would, excuse us, come together on the idea of “Hey Jude” being the A-side, they still needed to record it. For two nights prior to the official session, the band rehearsed the song, laying down 25 takes. During the actual recording, the band did four full takes, but chose the first one as the master for the song. Additional instrumentation and background vocals were added in the overdubbing phase, as was the final coda, which featured a 36-piece orchestra (producer George Martin provided the scoring for their parts). The final version of the single clocked in at 7 minutes and 11 seconds, a mammoth for its time.

“Hey Jude”

Many musicologists and critics have tried to dissect the appeal of “Jude” over time. The sing-along aspect certainly contributes to its popularity. It’s also a classic slow-build song in that it starts simply (McCartney on the piano, singing) as the other pieces gradually come in and build to the grand climactic combination of orchestra and stadium-pleasing “Na Na NA Na Na Na NA” refrain.

Music comes and goes, but The Beatles stubbornly refuse to fade. Dozens of their songs remain staples across a variety of radio formats, and surviving members McCartney and Ringo Starr have vital, ongoing concert and recording careers. The band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, and each member has received an individual induction (as has Martin and their original manager Brian Epstein). As for “Hey, Jude,” Rolling Stone ranked it at number eight on their “500 Greatest Songs of All Time.” It may be, without exaggeration, one song that nearly everyone on the planet knows. It certainly seemed that way when McCartney performed it near the end of the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Summer Games in London. To create music that cuts across all cultures and political differences . . . maybe that was the biggest revolution of all.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

News of the Week: Eagles Hit Number One, the iMac Turns 20, and Millennials Murder Mayonnaise

Michael Jackson vs. the Eagles, Round 36

I hear from a very reliable source that pop music is better than ever. I don’t happen to agree, but then again I’m an old fogey who is set in his ways when it comes to music, and would rather listen to my kitchen faucet drip all night than listen to something by Kanye West. (Note to self: get kitchen faucet fixed.)

There are a lot of people like that, and apparently they’re all buying Eagles and Michael Jackson albums. They’ve been battling for decades. Some years the Eagles’ Greatest Hits (1971-1975) is the number-one-selling album of all time, and other years Jackson’s Thriller is in the top spot. It just so happens that this week Don Henley and company can brag a little bit, though I’m not sure if it’s fair that a greatest hits album goes up against one specific album in an artist’s catalogue. Then again, maybe it’s impressive that one album can challenge a popular band’s greatest hits album. The Eagles 1976 album has sold 38 million copies, while Jackson’s 1982 album has sold 33 million (counting both album sales and online). Elaine’s boyfriend Brett must own several copies of that Eagles album.

Sure, the Eagles are No. 1 right now, but maybe Jackson will come out on top eventually. You know … in the long run.

The Computer That Changed Everything

I remember getting into an argument with a friend of mine in 1997 — actually, a friend of a friend — about the fate and future of Apple. He thought the company was about to go out of business, and I thought they would one day be successful again.

Admittedly, the company went through some really bad times in the ’90s, and it’s not like I had any psychic visions of the iPod or the iPhone (I’d have a bigger bank account if that were the case). But I did know that Apple made great things and that their customers were loyal. I knew they’d be back in a big way eventually.

Apple became the first trillion-dollar company a couple of weeks ago, and it really started with a computer I loved, the iMac (I owned the Bondi Blue one). It’s currently celebrating its 20th anniversary, and I wish Apple still made it, hockey puck mouse and all. It was retro and futuristic, nostalgic and forward-looking, all at the same time.

It’s amazing how the computer influenced not just the computer industry, but pop culture too. Other tech companies started to copy certain features (or lack thereof) of the iMac, and everybody started to release products with rainbow colors. That even continues to this day.

Walmart Honors Shopping Cart Lady

We all have our pet peeves: the little things in life that annoy us. Some of us can’t stand people who drive too slowly, and some of us hate it when people chew their food loudly or cough into their hand. I happen to believe that people who don’t return their shopping carts to the carriage corrals are on par with murderers and arsonists.

Honestly, is there anything lazier? You can’t take 10 seconds to place your cart into the corral after you’ve loaded your groceries into your car? Every time I go to the supermarket, I see random carts all over the place, blocking parking spaces and lanes. I’ve even seen people bring their carts to the side of the carriage corral and leave it there because they’re too damn lazy to bring it a few more feet around to the corral’s opening. It drives me crazy.

So a round of applause to 70-year-old grandmother Sue Johnson of West Virginia, honored by Walmart recently for returning her cart to the corral during a massive rain and wind storm. She got free grocery pickup for a year and a trophy shaped like — you guessed it — a shopping cart.

Think of Sue the next time you don’t return your cart when it’s 70 degrees and sunny.

The Cookie Cage

Score one for PETA.

In 2016, the animal rights organization wrote a letter to Mondelez International, the owner of Nabisco, to get them to update the front of their animal cracker boxes so the animals are out of their cages. Seems like the company actually listened. The new boxes recently made their debut.

Sure, we can be happy that the animal cookies (come on, they’re more cookie than cracker) are now free from their cages, but you know that five minutes later that lion sank his teeth into the giraffe’s neck.

Hold the Mayo

Those damn millennials. They’re responsible for the destruction of everything. They’re destroying the cereal industry because they don’t want to clean their bowls; they don’t go to the movies because they’d rather binge-watch something on Netflix; and they shun going on dinner dates for some reason. They even hate napkins! How are they wiping their faces after they eat their avocado toast and kale salads? With their sleeves?

You can now add mayo to the list of things young people don’t bother with. Yes, they’re mayo-haters, which means they’re missing out on creamy potato salad and tuna fish sandwiches the way tuna fish sandwiches are supposed to be made. One of the reasons is because they don’t like the texture and they think it’s too disgusting to eat. They do know they’re not supposed to eat mayo like ice cream, right?

I hate this story for the simple reason it has introduced me to the phrase “identity condiments.” I had never heard of that concept before and I’m sorry I know what it is now. Soon colleges are going to have to set up safe spaces for students who don’t want to deal with ketchup they don’t agree with.

By the way, can we stop blaming millennials for everything? Not that they don’t deserve a lot of the blame for RUINING EVERYTHING, but we have to direct our ire at the correct age group. Everyone seems to put any “young” person into the millennial category. People in their teens or 20 aren’t millennials! They’re … well, whatever generation comes after that. I have trouble keeping track of all of the different names. Generation Y? Generation Z? As a Gen-Xer, I prefer to call them “the generation who will never know what it’s like not to own a smartphone.”

RIP Barbara Harris, Kofi Annan, Don Cherry, and Miriam Nelson

Barbara Harris was an acclaimed Broadway actress who also appeared in such movies as Nashville, Family Plot, Peggy Sue Got Married, Grosse Pointe Blank, and Who is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me?, for which she received an Oscar nomination. She died last week at the age of 83.

Kofi Annan was a former secretary general of the United Nations and a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. He died Saturday at the age of 80.

Don Cherry was not only a top amateur golfer, he was also a popular singer in the 1950s. That’s him singing “Band of Gold” in the very first scene of Mad Men. Cherry actually died in April, but his death is just now being reported. He was 94.

Miriam Nelson was a dancer and choreographer who not only worked with such people as Judy Garland, Cole Porter, and Doris Day, she also worked on many Academy Award telecasts, worked as a choreographer at Disneyland, and even helped put together several Super Bowl halftime shows. She died last week at the age of 98.

This Week in History

Hawaii Becomes 50th State (August 21, 1959)

As if this summer’s eruption of the Kīlauea volcano wasn’t enough destruction from nature, the islands are now being hit by Hurricane Lane, which reached Category 4 status this week.

“Please Mr. Postman,” First Motown No. 1, Released (August 21, 1961)

The Marvelettes song was later covered by several other bands, including the Beatles and the Carpenters.

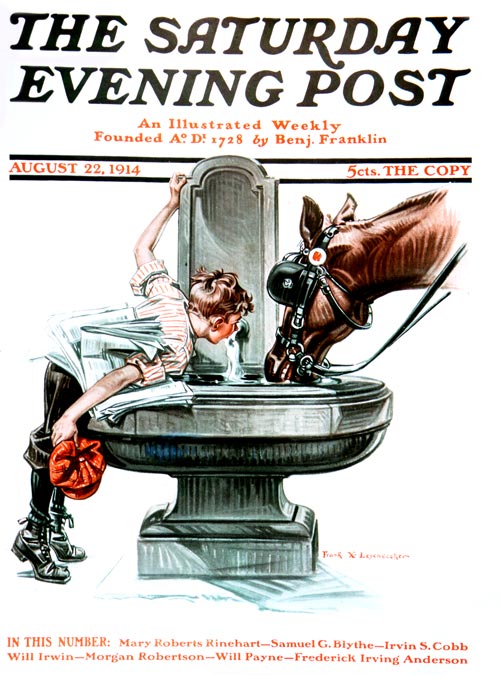

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Drink of Water (August 22, 1914)

The kid on this Frank X. Leyendecker cover should really put those papers down before he drinks from the fountain.

Frank X. Leyendecker

August 22, 1914

(SEPS)

Quote of the Week

“I might not rate her as the single greatest female vocalist of the rock era — Kelly Clarkson and Linda Ronstadt come to mind as more versatile across more genres and more varied in their emotional resonances …”

—an actual sentence written by Dan McLaughlin in his National Review obituary for Aretha Franklin.

National Waffle Day

You ever think of a food and suddenly realize you haven’t eaten it in years? That’s how I felt when I found out today is National Waffle Day. I’m not really a waffle guy and haven’t eaten them in probably 15 or 20 years. If I am going to eat something in that family, it would be pancakes or French toast. But if you like them, here’s a recipe from Curtis Stone for Whole Wheat Waffles with Strawberry-Maple Syrup. Seems like too much work for me. I’d probably just buy a box of Eggo.

Don’t get me wrong. Homemade waffles are good! They’re just not “Kelly Clarkson good.”

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

National Toilet Paper Day (August 26)

I don’t even want to know how you’re going to celebrate it.

U.S. Open (August 27)

The tennis tournament is marking 50 years of being an “open” event, with special celebrations and a brand new Louis Armstrong stadium, which has a retractable roof.

Smoke

She was suffocating, couldn’t suck in enough air, chest imploding. Aster grabbed the L-shaped plastic inhaler off the circular shelf on the standing lamp, pulled off the cover, emptied her lungs, closed her lips around the mouthpiece, and forced the top all the way down. A bitter taste filled her mouth while she breathed in deeply. She was supposed to hold the medicine in her lungs for as long as she could, which, as it turns out, was about three interminable seconds. She exhaled, drew in, exhaled, drew in … such a relief. What she really needed now, really, really needed, was a cigarette. She’d kill for a smoke. She didn’t care what Margie said, smoking helped her emphysema. Aster wished Margie hadn’t found her last pack and taken it away before she left for the hospital this morning. More like a prison guard than a daughter. Always looking for her cigs, throwing them away, sniffing like a hound dog for smoke. And this was Aster’s own big shaker-shingled house with a wrap-around porch. The one she and Billy bought well over 50 years ago, his law firm was doing so well. All this before she had stopped teaching when Margie then Tommy were born. How did this happen, the roles reversed, sweet little Margie now a lumbering old maid — a nurse who should have at least married a doctor — still living in the room she grew up in, ordering her around?

Margie could have done better, if only she’d listened. But to this day, the girl continued to wear those dowdy denim dresses, so-called natural makeup, flats with a skirt for goodness’ sake, and worst of all she absolutely refused to get her hair done. It just didn’t seem right.

And her son — once adorable, loveable, mischievous little Tommy. Why did he have to grow up into a discontent a 50-year-old man with a drinking problem? It struck her that Tommy was now almost as old as his daddy, her darling Billy, when he died suddenly. Neither of their kids ever married. What were the odds? And neither of them would ever give her what she wanted most, which was grandchildren. She wanted to smoke and she wanted grandchildren, was that too much to ask?

She turned her attention back to the golf game on television in her little den off the formal living room.

“He’s the number one putter this morning,” the sportscaster said. Then Justin Rose hit the ball, it stopped just short of the hole, and the crowd groaned.

Aster liked having the television on all the time. The silence would be deadly without it.

She got up, went over to her beautiful green antique desk, and took a glossy photograph off the top. It was a picture of what looked like a close-up of steak with pieces of coal imbedded in it. Margie had brought it home from the hospital.

“This is what your lungs look like by now,” she’d said.

Just looking at it hurt Aster’s chest.

What was to stop her from getting in her car, driving down the hill to the 7-Eleven, and buying a pack of Kents?

Nothing, that’s what. Except … Oh, who was she kidding. Margie was right, smoking was killing her. It was getting hard for her to play golf anymore, could hardly get through a bridge game without hacking up phlegm.

And she did promise Margie she’d quit. And she would quit. She’d quit right now just as she had three times before. She just had to get through this horrible indescribable period of craving. Her whole body ached for a smoke.

The question … the real question … the question everyone had to answer for themselves was: Why keep breathing?

And the only answer she could come up with, now that the kids didn’t need her, was this: It’s the moment-to-moment pleasures, pleasures as ephemeral as air — a thick grilled filet mignon with fried green tomatoes, the thwack on the ball with her driver … But the biggest, most reliable pleasure of all, was the one she’d just given up: the wonderful taste and dizzying feeling of well-being she got from her cigs.

The doorbell rang. It chimed in every room due to devices Margie had installed because she was tired of Aster never hearing it.

Aster slipped on her heels and walked through the formal living room. She could see her neighbor Jolene through one of the long windows on either side of the front door. She was probably coming around to raise money for one of her causes. Charitable work. That’s what seemed to be her reason to keep breathing. Aster put on a big smile and swung the heavy wooden door open.

“Hey Jo, come on in,” she said with a toss of her head.

Jolene was relatively young, in her early 50s; in fact, she’d gone to school with Margie. Aster often ran into her in the beauty parlor and they’d gossip. Jolene was wearing a nice polyester polka-dot blouse and white slacks, not a wrinkle in them. She’d done well for herself. Snagged the local banker, had maids and a cook, and had a married son, also a banker, with two sweet little granddaughters.

“Oh, I wish I could,” said Jolene. “But I have to canvas the whole neighborhood. Not a lot of volunteers came out for this one, and it’s such a good cause.”

She handed Aster a brochure with a photograph of a sorry-looking beagle on it.

“It’s for the Humane Society,” Jolene went on. “We’re having a hog-and-hominy fundraiser at the club.”

The club. Just the thought cheered Aster up. She’d wear her new kelly-green suit.

“I sure would enjoy that,” she said. “Count me in.”

Jolene wrote something on her clipboard.

“Before you run off,” Aster said, “could you do me a favor?” Just this one, then she’d quit. “Could you spare a cigarette? I’m plumb out.”

Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Top 10 “Bookish” Blockbusters

Saturday Evening Post movie critic Bill Newcott lists his top 10 favorite movies where books play a major role in the plot. He also reviews the home movie release of Book Club starring Diane Keaton, Jane Fonda, Candice Bergen and Mary Steenburgen, including interviews with Diane Keaton, director Bill Holderman, and writer Erin Simms.

Post Travels: Down the Shore — The Beautiful Beaches of New Jersey

Come summer, visitors flock to the Jersey Shore’s many boardwalks to eat salt water taffy, play mini-golf and take a whirl on beachside amusement rides.

But the stretch of coastline known as Long Beach Island is bit different than sandy neighbors. Affectionately known as LBI to regulars, summer days here are spent on the beach, swimming, surfing, fishing, and looking for passing wildlife like dolphins and rays.

There’s no boardwalk, but you won’t miss it. Climb the 217 steps up to the top of Barnegat Lighthouse, take a behind-the-scenes tour of the commercial fishing docks at Viking Village, or if you’re lucky enough to be in town for the annual lifeguard races, you can cheer as local squads battle it out for bragging rights.

The Debate Coach: Building Champions at Wiley College

Until the phone call, everything seemed normal. Chris Medina, the debate coach at Wiley College, had offered a scholarship to a student — a young man highly recommended by his high school coach. But there was a problem. The financial aid staff had never received the student’s diploma.

“I called him and said, ‘Hey — what’s going on?’” recalls Medina. “And he revealed that he hadn’t graduated from high school.”

The student was homeless. He was living in a hotel with his family, working at a Chinese restaurant, feeding them with takeout food from his job. But he also knew that Wiley, an HBCU (historically black colleges and universities) in Marshall, Texas, was his best path for a new life. After talking with Medina, the student earned his GED within two weeks and now has a 3.5 GPA at Wiley.

Medina loves telling these stories. When you ask about his achievements, he brags about his students, not his success as a coach. But let’s be clear: Medina’s teams win. A lot. Since he arrived at Wiley in 2011, the debate program has won more than 50 national championships, even though the 1,300-student college competes against much larger institutions. Medina’s students are shaped more by adversity than privilege, but debate has boosted their self-confidence and self-perceptions, igniting new ambitions and intellectual passions.

Medina experienced these same epiphanies in his teens. He grew up in a tough Los Angeles neighborhood, and he was “heading down the gang road,” as he puts it. His mother worked two jobs to support him and his brother. When he hurt his elbow playing football, the highly competitive Medina needed something to fill the void. He was intrigued by debate, so he joined his high school team — and hated it. “I was terrible my first semester,” he says.

Everything changed when he watched a dramatic interpretation, which in high school speech and debate competition involves performing a passage from a book or play. A teammate interpreted Dr. Faustus, and the would-be gang member was enthralled. “I didn’t know that was part of debate, and I said, ‘Wow — I want to do that.’” He never joined the gang. “I stopped hanging out with those guys,” he says. “My debate team became my family, and they encouraged me to be better than I thought I was. Until then, I didn’t know I was smart. I didn’t know that I could get into college, let alone graduate from college. This activity saved my life.”

The Wiley debate team has a deep and inspiring history. In the 1930s, the team, led by legendary scholar and poet Melvin B. Tolson, participated in the first interracial debate in the United States, the first interracial debate in the Jim Crow South, and the first at a white college. Over a 10-year period, Wiley lost just one match. In 1935, when they defeated the University of Southern California’s all-white national championship squad, the influential speech and debate association Pi Kappa Delta refused to recognize the victory. Students never forgot. In 2014, when Wiley became the first HBCU to win Pi Kappa Delta’s prestigious national championship, the entire team broke into tears.

That history is important to Medina and his students, and his determined teams have a rallying cry: “Uphold the legacy.” Sadly, when Tolson departed the school in 1947, the program ended, and it wasn’t resurrected until 2008, when actor and director Denzel Washington gave Wiley a $1 million gift. (Washington had starred as Tolson in the 2007 film The Great Debaters, and he pledged another $1 million to the program in January 2018.)

To encourage debate at all HBCUs, Medina has created an HBCU national speech and debate championship, which debuted in January 2018, thanks to a grant from the Charles Koch Foundation. Only about 10 percent of college debaters are students of color, and before the competition was announced, fewer than 10 HBCUs had debate teams. By the time the tournament was held, 22 teams were competing.

Subtle racism still exists in collegiate debating, Medina says. At one recent tournament, two students gave a speech based on the second studio album by rapper Kendrick Lamar, Good Kid, M.A.A.D City. A white judge disregarded it. “I just can’t connect to it,” she said.

More frequently, however, the competitions expose students, spectators, and judges alike to new thoughts and ideas. In the final round of a 2016 competition, one of Medina’s star debaters — a student who had overcome homelessness to win 15 national championships — discussed the need for more African-American coaches in speech and debate. His talk was like performance art: angry yet funny, a stinging, spellbinding one-man show mixing stage theatrics and historical thought. “In a world where we fear the ignorant, violent black youth, we must have an example of black excellence,” the student declared.

Medina believes passionately that the skills involved in speech and debate — empathy, respect, open-mindedness — are vital in an increasingly close-minded society. “When you live in an echo chamber, you don’t value what other people say,” Medina says. “The number-one thing that I teach my students is to respect other viewpoints — that everyone is entitled to an opinion. They need to see both sides of an issue.” Case in point: Team captain LaKiyah Sain strongly supports criminal justice reform, but at various tournaments she’s argued against it. “It was difficult,” she admits. “But you learn how other people think.”

Medina believes his job is to develop not just good orators and debaters, but strong, productive citizens. His students have become doctors and lawyers, teachers and coaches. And they are grateful for his guidance. “He’s so giving, and that’s something he instills in us,” says Sain, who wants to start a nonprofit for children raised by single parents. “That regardless of personal gain, you should think about others.”

Medina speaks proudly of a student who wanted to join the team but then disappeared for months. “Come to find out, he didn’t think he could do it,” says Medina. “His family told him not to take the scholarship. They didn’t think he could get his degree.” The student became a four-time national champion, and in May 2018, he’ll graduate with a master’s degree from Medina’s alma mater, Minnesota State University.

Over the past two years, 100 percent of Medina’s students have received scholarship offers to graduate school, which is no surprise. Success is part of the legacy.

Ken Budd is the author of The Voluntourist and the host of 650,000 Hours, an upcoming web series on travel and American heroes.

This article is featured in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Noisy Little Race: The Invention of Go-Karting

Two years ago, ingenious kids in Southern California built a few subminiature racers, powered with lawn-mower engines. Somebody dubbed them “karts,” and the name — and the spelling — stuck. Since then, 150 firms have come forward with such factory brands as Track Rabbit, GoKart, Bug, Gopher, Simplex, Puttnick. Prices begin around $125 for a two-and-a-half-horsepower assemble-it-yourself kit, and go to $600 for a chromed, 24-horsepower, twin-engine model.

Speeds range from 8 mph for the 6- to 12-year-old trade, to 70 mph for adults’ full-race versions. For teenagers, there are race meets all over the country, like this one at Uncle Bim’s midget track near West Palm Beach, Florida. Curves on this one-twelfth-mile oval hold speeds to 30 mph, and drivers are ruled by the “Palm Beach County Families’ Miniature Car Racing Association” — in short, mom and dad. These karts are about 70 inches long and weigh only 85 pounds. Roll bars protect Junior if he turns over. More likely, hard cornering will simply make his low-slung kart spin around and teach him a lesson: You can’t win going backward.

—The Face of America, November 21, 1959

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The State Fair

We take a look at the origins of the state fair, a deep-fried slice of Americana with a combination of old traditions and wild entertainment.

See more History Minute videos.

North Country Girl: Chapter 66 — “Dear Penthouse Forum…”

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

I was no longer a Viva editor, but being fired for cursing out my boss taught me to keep my mouth shut in the face of stupidity, a skill which kept me employed for forty years.

I was now the editorial assistant at Penthouse magazine, foisted on their staff by my old boss Kathy Keeton.

My new boss was Jim Goode, the executive editor, a scraggly 6’3” man with a bloodhound face who wore the same uniform of Levi’s, faded chambray shirt, and work boots every day, as if it were painted on him. Jim bore an unsettling resemblance to Lurch, the Addams Family butler, and laughed about as much, which was a good thing, as his gravely guffaw was blood-chilling, like the clanking of rusty chains.

My first task at Penthouse was to introduce Jim Goode to his newest, and probably unwanted, staff member.

I poked my head into his office. “Mr. Goode?” He looked up from the papers on his desk, fixing me with a blood-shot, Medusa glare.

“What do you want?” rumbled forth like an early warning vibration from a thundercloud.

I sidled into his office, hugging the wall. “I’m Gay Haubner, ah, I was the assistant editor at Viva, and ah, Kathy Keeton thought I might fit in better at Penthouse.”

Jim did not think this worthy of a reply but kept staring at me.

I was pretty sure any talent I had at being charming would fall on stony ground but I had to try; I knew Jim had been fired at least once from both Penthouse and Playboy, so I was hoping for a sympathetic ear.

“Ah, Mr. Goode…”

“Jim.” I took this as permission to approach.

“Ah, I heard you met Marilyn Monroe?” I thought this was an excellent conversation starter. As a reporter, Jim had covered the set of The Misfits for Life magazine, and I had been a fan of Marilyn since I was ten, when I saw Gentlemen Prefer Blondes on Saturday Night at the Movies.

“She was pasty and white, like a loaf of bread dough. If you took her arm,” here Jim grasped my wrist with his huge paw, “there would be deep indentations in her skin that lasted for days.” He released me with a shake. “Get out of here, Haubner.”

From that day forth, Jim never called me by my first name. “HAAAUUUBBNEER” he would boom out, summoning me from my lean-to in the back of the secretarial pool.

No one had clued me into what my responsibilities at Penthouse would be, but I quickly found out that the most important part of my job was taking Jim Goode to lunch, a chore I shared with the rest of the editorial staff.

Cruising on Penthouse’s oceans of cash, all the editors, even the lowly, just-hired editorial assistant, enjoyed a generous expense account. Jim was not about to use his own expense account on anything so unnecessary as a meal (he ate almost nothing, getting through the day on three lunchtime vodka martinis).

He had other things to pay for: his pampered mutts, his almost as cosseted dancer boyfriend, Kevin (who looked like a Ganymede come to life from a Renaissance painting), and French advertising posters from the early 1900s. Jim owned so many of these framed posters that there was no room to hang another in his Greenwich Village townhouse. They rested in stacks against the wall, the target of the occasional raised leg of an underwalked dog.

I’m not sure Jim Goode and I became friends. I can’t even say that he had friends. We did spend a lot of time together, at midtown restaurants, in the office, and at his place. I amused him, like a misplaced Pomeranian he picked up at the Bide-a-Wee animal shelter.

By the end of my first week at Penthouse I had taken Jim out to lunch once for crepes and martinis at The Magic Pan and twice at Mary’s, a bare-bones, fluorescent-lit joint that served unseasoned food and oversized, very strong drinks, and I still had no idea of what my editorial duties would be. I was tottering back from one of these lunches when I was stopped in the hall by a handsome young man who stuck out his hand.

“Hi, I’m Robert Hofler. You’re the new editorial assistant, right? Come into my office.”

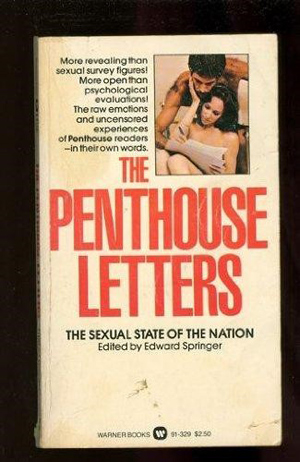

Robert placed on his desk a bulging manila envelope and that month’s issue of Penthouse, open to the letters to the editor.

Robert Hofler beamed as if he were about to give me a Major Award. “You’re going to be taking over the Penthouse letters!”

Robert had thoughtfully selected and marked up the next issue’s letters; using the tip of his thumb and index finger, and trying not to make a face, he fastidiously pulled out a few letters from the envelope to show me what to do. After that, I was on my own.

Penthouse Letters was the editorial staff’s least favorite section and (according to market research, which was squashed as did nothing to help ad sales) the most favorite of the Penthouse readers (that they actually read, as opposed to just gaping at photos of nude women). Bob Guccione, with his love of all things pseudo-Roman, titled the readers’ letters “Penthouse Forum.”

In a normal magazine, letters to the editor express the writers’ agreement or disagreement on articles in previous issues. In men’s magazines, they also include comments on the hotness of Playmates or Pets or Vixens or what have you. At some point in Penthouse history, readers began sending in letters hot-dogging their wild sexual experiences, always starting with “I know you won’t believe this but it’s true.” An extremely profitable spin-off, the Reader’s Digest-size Penthouse Forum was nothing more than letters too filthy to run in the magazine, accompanied by cheaply reproduced black and white photos of past Pets who had signed away all their rights in perpetuity.

Editing the letters section was the scut work of Penthouse, a task that had plagued almost every editor (even the gay ones, who must have looked on these letters as missives from Mars), and which was dumped as rapidly as possible on someone else. Low woman on the editorial totem pole, that was now me.

Every day, a Santa-sized bag was dragged through the secretarial pool and dumped on my desk. I was supposed to read through all the letters, looking for those gems that would titillate readers, which I typed up, correcting grammar and spelling, and embellished if the letter wasn’t detailed enough. I soon learned to recognize and dispose of letters that came in envelopes with odd red stamps. These were from prison inmates; their sexual adventures, real or made up, too often came to violent ends. After opening one letter and having what appeared to be pubic hair drift onto my desk and lap, I started squeezing each envelope before I opened it; if it felt like it contained anything besides paper, it went right in the garbage.

I can’t imagine who found this amateur pornography arousing. Letter after letter, usually scribbled in pencil on stained paper torn out of a loose leaf notebook, lovingly described encounters with randy next-door neighbors, lonely widows, incestuous sisters and aunts, vacuum cleaners and fish tanks; of adventures that occurred outdoors, in stuck elevators, bus station bathrooms, and office supply closets.

After a few months, I started casting about for anyone else I could dump this nasty hot potato of an assignment on. Each day’s mail delivery left me feeling queasy. I developed an obsessive-compulsive disorder, scrubbing my hands a dozen times a day and taking a half hour steaming hot shower as soon as I got home. I turned my back and scooted away from my boyfriend Michael in bed, claiming I was too tired or in the middle of a fascinating book. Penthouse Letters was killing my sex drive.

I could not find anyone to take this discouraging smut off my hands. I approached my first friend at Penthouse, Kathy Lowry, the on-staff writer for girl copy, responsible for transforming big-breasted, small town girls into exotic women of the world. (She was especially good at names: ho-hum Dottie Meyers became the exotic Dominque Mauré.) Kathy and I had become pals when she was suffering from writer’s block, brought on by the daily tumult of her love life.

“I’ll do it, I’ll write the copy for ‘It Takes Two to Tango,’” I volunteered, relieving her from the task of coming up with a backstory to explained why two dark haired beauties had decided to shed their flamenco dresses to engage in the forbidden dance.

Now when I asked her to return the favor, she said “Uh-uh.” Kathy turned me down with a “You can’t fool me” look. “I did those letters for a while. I have enough problems with Larry as it is.”

Kathy was a blonde Texan, lanky and wide-eyed with a slow drawl that disguised how whip smart she really was, and Larry was Larry L. King, a writer who was raking it in from his Tony-nominated musical “Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.” Larry had a reserved seat every night at Joe Allen’s while Kathy was churning out the deep thoughts of a Penthouse Pet who had one hand between her legs and the other clenching a fake pearl necklace. Kathy was convinced that Larry’s meteoric New York success meant that she would lose him. My work days began in Kathy’s tiny windowless office, listening to her whoop over what she and Larry had done the night before, or if she had spent the evening alone waiting for the phone to ring, tending to her crying jags, patting her on the back and handing her Kleenex. (After “Whorehouse” closed, a stinker of a sequel, “The Second Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” ran for all of a week. Kathy dragged me to opening night, where I sat goggled-eyed and opened-mouth with the rest of the non-paying audience, gobsmacked that such a piece of shit could actually be staged on Broadway.)

I tried to return Forum to Robert Hofler, who laughed at my presumption. “Are you kidding? I’m not taking Letters back. I’m already stuck with Xaviera; she refuses to work with anyone but me.” Robert was officially the entertainment editor; I guess entertainment encompassed the dubious sex advice doled out by Xaviera Hollander in her Ask the Happy Hooker column.

I went crying into the office of my second friend at Penthouse, Senior Editor Peter Bloch. Peter usually welcomed any interruption from his job, which was to maintain a delicate balance between Jim Goode’s insanity and Bob Guccione’s insanity. Jim was rabidly anti-government, which, considering he owed thousands of dollars to the IRS, was not surprising. Convinced that the CIA had a file on him, Jim ordered Peter to find investigative reporters who would uncover their dastardly deeds and secrets; many of these writers did ground-breaking work that was almost always ignored by the media establishment and probably by the average Penthouse reader as well.

Guccione wanted Peter to find reputable science writers who could blow the lid off the medical establishment’s suppression of dubious cures for cancer. (Guccione succumbed to cancer of the tongue a few years after Kathy Keeton died of breast cancer.)

The Jim Goode/Bob Guccione Venn diagram met with their shared obsession with the mysterious Trilateral Commission; in their eyes, these shadow men were the modern day Illuminati, bent on world domination, as evil as any comic book cabal. I think Penthouse did a twenty-part series on them.

“I can’t edit the letters anymore, Peter,” I wailed. “I’ll end up with no boyfriend and no skin on the palms of my hands.”

Peter rescued me. “We’ll give the letters to my secretary,” a woman who was gasping for her own promotion to editorial assistant.

This was great news but left open the question of what my job would be, outside of picking up Jim Goode’s three-martini lunches. I regarded these lunches as on-the-job editorial training, prepping me for whatever my real job at Penthouse would be. Jim spent lunch lecturing me on the evils of Guccione, Hefner, and the entire Penthouse advertising staff, and almost convinced me that if it were left up to him, Penthouse would have the editorial integrity of The New Republic.

These two-hour, well-lubricated lunches also taught me to do all my work in the morning. Between nine and one I was a beaver of an editor: if Frank Gilbreth had stood over me with a stopwatch, he would have been floored by my efficiency.

Treehouse Hotels Offer Luxurious Arboreal Escapes

Love fall foliage? This year, rather than simply seeing the scenery at ground level, go out on a limb — and check into a treehouse hotel.

These soaring scenic suites — accessible via adventures involving winding stairs, suspended bridges, and dizzying inclines — provide complete immersion into the autumn forest, delivering the scents, sounds, and panoramic peeps of shifting shades and colors as the sun moves across the sky.

Some treehouses are modest, simply mirroring their rustic surroundings. Others aim to indulge, providing lofty amenities like floating hot tubs, glass-enclosed bedrooms, and crackling fireplaces.

Here are three of our favorite elevated accommodations, where you can channel your inner Swiss Family Robinson. Don’t forget to pack your binoculars!

Out ’n’ About Treehouse Treesort

Cave Junction, Oregon, treehouses.com/joomla

Scenic Setting: A horse ranch in Oregon’s Siskiyou National Forest.

These airy abodes are not for the fainthearted. Many require treks up towering staircases, strolls across suspension and swinging bridges, and operating hoists for lifting luggage. Each is unique, ranging 12 to 47 feet above the forest floor. Interiors are cozy but rustic, offering loft and bunk beds, sinks and toilets — but showers are in the main lodge.

Leaf Peeps: A palate of oaks, willows, and red maples within a sage-toned patchwork of evergreens.

Other amenities: Horseback riding, zip lines, arts and crafts, full breakfasts, and the annual World Treehouse Conference (Oct 5–7), teaching building and climbing techniques.

Rates: $150–$330.

Treehouse Cottages

Eureka Springs, Arkansas, treehousecottages.com

Scenic Setting: Secluded pods perch amid the Ozark wildlife forest, but just minutes from town.

Climb tall staircases or hop-step across swinging bridges to one of eight lifted lodgings outfitted with floor-to-ceiling windows, glass-enclosed, heart-shaped hot tub, fireplace, luxe linens, antique furnishings, and wrap-around decks.

Leaf Peeps: White ash trees showcase rich shades of red, violet, yellow, and green, often within the same tree. Black gums take on brilliant purple and scarlet tones. Practically every view is accented with maples, sassafras, and cedars.

Other Amenities: A private hiking path meanders around the woods, descending to a natural cave and spring. The gift shop offers a variety of local, handmade wares, including pottery made in a studio on the grounds.

Rates: $149–$179.

Treehouse at Moose Meadow Lodge

Waterbury, Vermont, moosemeadowlodge.net/treehouse

Scenic Setting: Look out upon 86 acres pristine Vermont forest.

Enter this two-story, Wi-Fi-enabled treehouse via a stairway circling a maple tree. Level one features a full bath, living and dining areas, and a wrap-around deck. Above is a queen bed loft dressed in cushy bedding and a balcony with panoramic vistas.

Leaf Peeps: Sun-strewn eastern cottonwoods, orange-brown chinkapin oaks, and crimson sugar-leaf maples.

Other Amenities: Hot tub, trout pond, hiking and biking along the Green Mountain byway, and craft breweries in nearby Waterbury. Request “tree-service” at breakfast and hotcakes will be delivered to your door.

Rates: $475–$525.

Other Treehouse Stays

Treehouse accommodations from the primitive to the palatial are sprouting up around the U.S. Check out these as well:

Buckhead Treehouse, Atlanta, Georgia, airbnb.com/rooms/1415908

One of Airbnb’s 2017 “Most Wished-For Properties,” this Zen treehouse, buried in an urban neighborhood, comprises three rooms (named Mind, Body, and Spirit) connected by rope bridges.

Cyprus Valley Treehouses, Spicewood, Texas

cypressvalleycanopytours.com/lofthaven

Connected to a canopy tour operation on a ranch, these wooded treehouses are suspended among the tall cypress trees. Each treehouse is a little different, and some amenities include queen beds, a rope-bridge-connected bathhouse with a waterfall feature, an outdoor shower, and wrap-around porches. Add to the adventure with a zip-line tour.

Historic Banning Mills, Banning, Georgia

historicbanningmills.com/lodging/adventure-room-packages/

Book an adventure package to enjoy zip-lining and wine-tasting during the day. In the evening, enjoy a dinner for two and then relax beside a gas-log fireplace in a luxuriously outfitted treehouse accessible via a sky-bridge, on a 300-acre wooded adventure resort above The Snake Creek Gorge.

Post Ranch Inn, Big Sur, California

postranchinn.com/accommodations/tree/

Triangular cottages on stilts perch above the forest floor and offer private decks, digital stereo systems, wine, snacks, and skylights for stargazing while lounging in an organic-linen-sheeted bed.

River Road Treehouses, New Braunfels, Texas

These treehouses are the opposite of roughing it. Overhanging a wet-weather creek that feeds into the Guadalupe River, these forest digs offer frou-frou creature comforts like Wi-Fi, satellite TV, well-stocked kitchens, and king-sized beds.

Treehouse Point, Fall City, Washington

This rustic adults-only tree-cabin resort only 30 minutes from Seattle offers morning yoga, evening campfires, and homemade breakfast. It’s a great place to book for a wedding, or just for an elopement. Try to snag the Temple of the Blue Moon cabin, which overlooks Washington’s Raging River.

Treehouses at Primland, Meadows of Dan, Virginia

The super-luxe treehouses at this 5-star sporting and nature resort are delicately balanced atop trees on a Blue Ridge mountain peak, overlooking Kimber Valley, North Carolina.

This article is an expanded version of the interview that appears in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

“Love Dies Slowly” by Eileen Tighe

Summer is for steamy romance. Our new series of classic fiction from the 1940s and ‘50s features sexy intrigue from the archives for all of your beach reading needs. In “Love Dies Slowly,” an illustrator will seek a tender affair with her son’s headmaster if she can ever move past the recent death of her free-spirited journalist of an ex-husband.

It had been raining for 10 long days, a steady, relentless downpour that dampened the human spirit as well as the good brown earth. One dreary day followed another with monotonous regularity. The river looked black and threatening and the hedges along its banks were hardly visible through the heavy mist. Even the small ferryboat that crossed from shore to shore had disappeared from sight, but its foghorn tooted eerily all through the day and night. I was working in my studio, an upstairs room with a view of the river and its far shore, when I heard the front door open unceremoniously and close with a shattering bang.

“Chip!” I called. “Haven’t I asked you not to use the front door?”

“It’s raining, Maggie.”

“I know, dear. That’s why I want you to come in the back way.”

“Roger,” said Chip. “Over.”

“Please don’t track up the house. I’ve just finished straightening it.”

“Roger. Anything to eat?”

“Sandwiches in the pantry. Milk and soda pop in the refrigerator.”

“Mille grazie,” said Chip. “Yatcha lubia.”

I went back to my drawing board and the sketches I was doing for a new children’s book. My son walked into the studio nibbling on a three-decker peanut-butter sandwich and drinking his pop from the bottle. His bright hair was wet with rain, but it was as rebellious as ever. He was growing so fast that nothing seemed to fit him. There was always a space around his ankles and his wrists that remained uncovered.

“Are you still working on that silly old book?” he asked.

“I’m working on 500 silly old dollars,” I replied.

His eyes clouded. They were very expressive eyes, full of joy or sadness or wonderment or laughter. He had the fair hair and skin and the chiseled features of his grandfather, but the great dark eyes were strictly his own. They had a disturbing way of looking straight through you and of always seeking the truth. He came over and put an ice-cold pop-bottle hand on my shoulder.

“I love you, Maggie,” he said. “I wish you didn’t have to work so hard.”

He was so sincere and so very young and vulnerable that I longed to put my arms around him. But he was growing up and he didn’t like to be babied.

“I love you, too, darling,” I said, “and I’m a very fortunate woman. I have a wonderful son and work to do that I enjoy. By the way, did you see the lunch box in the pantry?”

He nodded.

“I thought you might like to take it down to your friend, Aristotle. It must be difficult to navigate a ferryboat in this fog.”

“It’s spooky,” said Chip. “Aristotle says that fog is celestial, but I don’t agree. It’s unearthly all right, but it’s not divine. It’s cold and clammy, and it wraps itself around you and blots you out of sight. It’s not like flying through a cloud. It’s more like vanishing into a vacuum.”

“Sounds like a good idea for a composition.”

“I wrote one on it last week and Mr. O ‘Hara told me today that it may win a prize. He was in Japan, Maggie. When we were there.”

“Is that so?”

My son gave me a long, searching look. “He said he met you once in Lisbon and once in Singapore. He said you might not remember him, but he’d like to come over and talk to you. He asks me about you all the time.”

I remembered Mike O’Hara very well. He was a brilliant, charming, supercharged correspondent; a romantic type who got into trouble with a colonel’s wife. I was surprised when I heard he was teaching at Bolton, because he was a really gifted journalist and his father owned a chain of New England newspapers.

“I remember him, Chip.” I said, “but I’m not ready for people yet.”

“It’s almost a year, Maggie.”

“I know, darling, but let’s wait until summer. We’ll invite all your new friends to come and see us and I promise to be very gay.”

Chip studied me in silence and then he washed down his thoughts with the bottle of pop. “OK.,” he said, “but I wish summer would hurry.”

“You know what I wish? I wish you’d stop drinking out of a bottle.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s so unaesthetic. Nice people don’t drink out of bottles.”

“Around here they do. Everyone at school does, and so do the guys at the gas station. Why, even Eddie Fisher drinks out of a bottle on television.”

I couldn’t argue the point because, presumably, these were nice people. “How about the great Mr. O’Toole?” I asked.

Chip grinned. “Y’got me there, Maggie,” he said. “You really got me. I don’t think Mr. O’Toole drinks out of a bottle. He has a mother too.”

“So I’ve discovered. His mother called me today.”

“Did she invite you to tea?”

“Yes.”

Chip whistled shrilly through his front teeth. “That means I’m in some kind of trouble,” he said thoughtfully.

“I got that impression too. Have you any idea what kind of trouble?”

Chip’s eyes widened anxiously. “No, Maggie, I haven’t,” he said. “What did you say to her?”

“I thanked her, but I regretted. I asked her to have Mr. O’Toole call me.”

“And did he?”

“He called and I invited him to dinner.”

“Well, hallelujah!” my son exclaimed. “Will she let him come?”

“Who is she?”

“Macushla, his mother. They say she won’t let him out after dark.”

“Chip,” I said incredulously, “didn’t you tell me that Mr. O’Toole is over six feet tall, weighs almost 200 pounds, and won all kinds of medals for shooting down planes over Europe?”

“Roger. What’s for food?”

I couldn’t help smiling, although I knew this wasn’t a celebration. There was, as my son said, some kind of trouble ahead. But Chip’s eyes were so bright and his cowlicks so unruly that I put my arms around him and gave him a kiss of confidence.

“Your favorite menu, darling,” I said, “and I think you told me it was also a favorite of Mr. O’Toole’s. Steak and apple pie.”

Mr. O’Toole is not only the current authority in our home on everything from Bach to Buchmanism, he is also the headmaster of Bolton, a small private school for boys. It is an old and venerable institution — my father is an alumnus — with a granite façade and disciplinary ideas that are as rock-ribbed as the New England town whose name it bears. It is not a school I would have chosen for my son — mainly, I think, because father is one of the trustees — but when Jeff was killed, father took my affairs in hand, enrolled Chip in Bolton and, because I refused to be separated from him, installed us in this old house which was once the family’s summer home.

Mr. O’Toole was, as my son had so accurately reported, very tall, unemaciated and well-mannered. I was sure he did not drink out of a bottle. He greeted me gravely, hung up his coat in the hall closet and followed me into the long, low-ceilinged living room that looked out through many windows to the river. There was a fire sputtering on the hearth and Mr. O’Toole crossed the room and stood in front of it.

He studied me silently for a second or two and then he said, “I’ve been waiting a long time for this moment.”

It was a provocative opening, but I chose to ignore it. “Chip talks about you constantly,” I said. “You’re one of his real heroes.”

“Before I knew who you were,” Mr. O’Toole continued, “I noticed you driving around the village in an open car. When I inquired about you, I learned that you were an artist and that you were married.”

I couldn’t think of any reply, so I didn’t try to make one. If he had discovered that I was married, he must know that Jeff was a journalist and that we were out of the country most of the time. We never settled down, we never had a home, but we always came back to Bolton. We both liked the old town and the old house, and that was why father thought I would be happier here than anywhere else.

“When your husband was killed,” said Mr. O’Toole, almost inaudibly, “I wanted to write to you, but I was afraid you might think it intrusive. Grief is a very personal thing.”

It was well-spoken and hard to say, and I tried to smile my thanks. “It’s an emotion that can’t be shared,” I said. “I guess that’s why I haven’t been able to face people. You’re the first guest since the accident.”

“I’m honored.”

“And I’m grateful,” I said, “for all you’ve done to help my son.”

“Your son,” said Mr. O’Toole, with a rather shy smile, “is a very unusual 10-year-old. I’ve learned a great deal from him.”

“He’s led an unusual life.”

“It’s been a rewarding one for him in many ways. He’s impressionable and he has a remarkable memory. But you can understand that his background has made it rather difficult for him to adjust to a normal life with boys of more routine interests.”

I knew this was educational double talk, and while I had no doubt that it was sound, I had little patience with it. If I have a blind spot, it is for my son. I think he’s exceptional. I know that he’s honest, kind and courageous. If the boys of Bolton School found it difficult to get along with him, the fault must be theirs. But I didn’t want any trouble. It would bring my father to town on the run, and father is a man of action. He is also fanatically proud of Chip, who so closely resembles him that even strangers remark upon it.

“I don’t know what the problem is,” I said, “but I was thinking today that if Jeff were alive he would say the net result of normal living, in Chip’s case, is that he’s learned to drink out of a bottle.”

Mr. O’Toole smiled. “I’ll have to confess that it’s normal,” he said, “but it’s only a phase. There is a serious problem that I must talk over with you, and I thought we might set up a meeting with the faculty on Saturday, if that day is convenient for you. We can get together in my office and discuss things informally.”

“A serious problem? Has Chip done something dreadful?”

“Not at all,” said Mr. O’Toole. His voice had a soothing quality that was very reassuring. “It’s an educational hurdle that we can’t seem to solve. It has nothing to do with discipline. Believe me, Mrs. Hillyer, I’m very fond of your son. By the way, where is he?”

“In the pantry. Reading a book on how to mix drinks.”

“Has he ever mixed one?”

I shook my head. “Never, but he feels that it’s one of his duties, now that he’s the man of the house.”

“Do you think he’d mind if I gave him a hand?”

“I don’t know. He’s rather touchy about his new responsibilities. I’m sure he’s anxious to impress you, but I’m afraid the result may be lethal.”

“Whatever he concocts we’ll have to drink.”

“That’s what worries me,” I said. “I’ll leave it up to you, Mr. O’Toole. You’re his best friend.”

“If you’ll excuse me,” he replied, “I’ll see what I can do. And please call me John. I’m your friend, too, Mrs. Hillyer.”

On the following Saturday, a day distinguished by brilliant sunshine, I drove across the hills to Bolton School. The week had been an eventful one for me. I was beginning to live again. I had done a lot of thinking and I had found a friend in John O’Toole. It was good to have someone to talk to and I was rediscovering the joys of companionship. I had been too long alone and I had forgotten how exciting it was to be alive.

When I turned in at the gates I was struck with the beauty of the place. The grounds were handsomely planted and there was an air of serenity in the tall trees, the sweeping lawns and the ivy-covered buildings. Seclusion, protection, security — they were all here. These were the things that Chip had never known and I wondered how much they might mean to him, now that he had been given a chance to sample them. He had grown up in many lands; he never had a real home, no close friends, no formal schooling. He learned as he grew by asking questions, and he got his answers from the experts. He went with his father to political meetings, to military headquarters, to palaces and parliaments, to interviews with people of all kinds. And he went with me to market places and museums, to concerts, luncheons and receptions. He talked to anyone and everyone who would talk to him and he learned to speak many languages.

It was not a life my father approved of for a growing boy, but it was the way Jeff wanted it and the only way he would take ii. For Jeff there was no tomorrow; there was only today. If I tried to talk about the future, about a home, about settling down and giving Chip a chance to grow up normally, to have roots and security, I found that I was talking to myself. My loyalties were divided, but I couldn’t find any way out. A boy needs a father even more than a home. So we followed him. We followed to the end.

My marriage, which had ended so abruptly in an airplane crash, was one that father had opposed bitterly, but when his grandson was born he became reconciled to its existence. Now that he was in the driving seat, financially and paternally, he would be hard to handle. He expected a lot of Chip. And he expected even more of the school. Since he was a trustee, it would be like him even to demand a certain amount of special consideration for his grandson.

I parked the car and walked across the pebbled path to the front entrance. I had dressed carefully, with what I hoped was proper solemnity for the occasion, but I felt depressed and inadequate, and wondered if I could rise to whatever the situation demanded. I would never forgive myself if I let my son down with tears or emotional protestations or anything that indicated a soft upper lip.

The door was opened by the headmaster himself, who welcomed me with a friendly smile. “I’ve been on the lookout for you, Maggie,” he said.

“Thank heaven you’re here,” I replied. “I’m beginning to panic.”

“It won’t be that bad. Let me have your coat.”

He led me into a book-lined room with a long table in the center of it. There was a large stone fireplace on one wall and on the other a great bank of windows looked out over the lawns to the river far below. The masters, who were assembled around the long center table, were young or youngish men, conservatively clothed in more subdued fashion than the ubiquitous gray-flannel suit or the journalist’s unpressed tweeds. There was one exception. Mike O’Hara looked as dashing and as handsome as he had several years ago in Tokyo and Singapore and Lisbon. He came over and took my arm and guided me toward the fireplace.