Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: The Story of Dan

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

“HI, Dan, how are you today?”

Dan walked toward me with his arthritic limp, grinned, and held out his hand. “Better than I was,” he answered predictably, “but not quite where I wanna be.”

Dan was a client I always looked forward to seeing. A witty 46-year-old, he owned a flooring business in a nearby town. He’d managed to finish college after a childhood of poverty, worked hard, and built his business from the ground up. He often smiled as he talked about his loyal employees, many of whom had stayed with him since the business opened 15 years earlier. When he talked about his family, Dan’s eyes would soften and shine. “My wife is the greatest woman in the world. My daughter’s getting married in the fall and my son will graduate with his engineering degree next spring.”

Dan was living a life that far exceeded his childhood dreams. Though not wealthy by Wall Street standards, in his mind he was the richest man in the world. However, while living the American dream Dan had ignored his health to focus on business and family. Although his doctor advised him to make lifestyle changes, Dan didn’t follow that advice. His wife worried about his weight, bad knees, and rising blood pressure. He responded to her concerns with his usual you-only-live-once, happy-go-lucky attitude and continued his unhealthy patterns.

Dan’s eating habits were to blame for his worsening health. He often bought lunch for his entire office staff and would eat whatever they ordered on any given day. Although his wife was willing to cook, Dan enjoyed taking her out to eat. He spent most evenings winding down with one or two rum and cokes and a salty snack or two. This lifestyle led to a steady weight gain over ten years.

An eye-opening experience led Dan to seek treatment at our center. One morning after a restless night of sleep, he decided to check his weight. Maybe the seeds planted by his wife or doctor had started to germinate, or perhaps for some reason he noticed the dusty scale tucked away in the bathroom closet. He dragged the old analog scale out from behind a box of cleaning supplies, set the scale on his tiled floor, and stepped on the black rubber surface. The red dial quickly snapped to the 300-pound maximum and vibrated slightly as it tried to go beyond its limits.

Dan was shocked. He had no idea he weighed that much. “This is really bad,” he muttered. “I can’t even weigh myself on a normal bathroom scale.” All day he thought about his weight, his blood pressure, the difficulty he had playing a round of golf, and the sleep apnea that left him feeling drowsy throughout the day, even occasionally dozing off at his desk during work. And he had pain. A once-in-awhile ibuprofen pill had become a regular medication to help him walk during the day and control the knee pain that awakened him in the middle of the night.

Dan’s wake-up call came from seeing that red dial max out on his bathroom scale. He realized if he didn’t stop this weight trajectory, he wouldn’t be able to live the way he wanted — and he had a lot to live for.

Dan’s motivation translated into action. Every two weeks he came to my office, down another four or five pounds. Occasionally Sheila, his office manager, called to tell me Dan was running five or ten minutes late, but he never missed.

After five months of treatment, Dan had lost 60 pounds. He was playing more golf, helping prepare dinners at home, and his office staff had shaped up too, keeping the refrigerator stocked with fruit, raw veggies, and low-fat dip to accompany the sandwiches they ordered for lunch. Dan told me Sheila and one of his salesmen had lost over 20 pounds each since he started the program.

Even though he’d found his groove for weight loss, Dan wanted to keep meeting with me every other week because it kept him accountable. We discussed that at some point in time things would get harder and he accepted this as a challenge.

Then one day Dan didn’t show up for his usual Tuesday afternoon appointment; Sheila didn’t call either. Somewhat concerned about his out-of-character absence, I called his personal phone and office phone, but nobody answered, so I left messages. No one returned my call. A week went by and I called his home phone and again had to leave a message. A month had passed and I had thought a lot about Dan. Why did he stop treatment? Although I don’t make a habit of harassing patients who no longer want to remain in treatment, Dan wasn’t a typical patient and his absence didn’t make sense. “I’ll try one last time,” I thought. Like before, six rings and voice mail. Three weeks passed and finally I got a return call.

“Hello Dave, this is Suzanne Smith. My husband Dan Smith was one of your patients at the weight loss center.”

“Of course, Suzanne, thank you for calling me.”

“You left a couple of messages for Dan and he wanted me to call you. He would talk to you himself, but he’s very sick and weak. A few days after you last met with him he started to have abdominal pain and nausea that wouldn’t go away. He went to his doctor and at first they thought it was his gallbladder. Then they ran some other tests and found out he had pancreatic cancer.” She spoke in a matter-of-fact, well- rehearsed tone.

My throat tightened. “Oh, no, I am so sorry, Suzanne.”

Her voice softened as she explained his prognosis. “The cancer is progressing fast and there isn’t much we can do other than try to keep him comfortable. We wanted to thank you for your help; Dan felt so good until his symptoms came on all of a sudden.”

“I can only imagine everything that’s going on for you guys right now, and your call means a lot to me. Please tell Dan hello for me.” I hung up the phone and stared at my office wall.

The news shattered my expectations. Dan worked so hard to change his lifestyle — and what was his reward? The things we both believed would prolong his life probably wouldn’t give him a single extra second on this earth. Everything he worked for was taken away without warning. I wondered if he had regrets. If Dan had known he’d become so ill, would he have tried to lose weight? About three weeks after my conversation with his wife, Dan died.

I decided to attend his wake with the plan of quietly signing the registry, introducing myself to his wife, and then leaving. I wanted to pay my respects, and to be honest, I needed to find closure to my relationship with him. I arrived at the funeral home to find the parking lot overflowing with cars and a mass of people gathered outside. I quickly realized what I learned about Dan in a clinical setting only scratched the surface of who he was and the impact he made on people in his community. The visitation line stretched from the front to the back of the seating area and then twisted back and forth in the foyer like an amusement park line. The length of the line told me it would be hours before I reached the front to pay my respects. On another night I might have been able to wait, but that night I needed to lead a bariatric support group.

Even though I wouldn’t be able to see Dan or his family members, I wanted to stay as long as possible. So I stood in the back of the barely moving line, far from the seriousness of what was taking place at the front of the funeral home. No one was crying, hugging, or being introduced to family members. I couldn’t hear anyone saying “I’m so sorry” or “If you need anything, please let me know.” At the back of the line I was in a space somewhat removed from the emotion, stuffed into the foyer with seventy or eighty other people. I saw middle- aged people with their young adult children waiting in line. These were probably families who knew Dan through his kids. I spotted a few fidgety men wearing khakis and three-button shirts who seemed to be talking about sports or something more superficial than the event of the evening. “Golfing buddies,” I told myself.

I listened to the conversation from a small group of Dan’s close friends in front of me. They had seen him regularly over the past year and began discussing his intentional weight loss as well as the weight loss he suffered from cancer.

“He looked and felt so good before he got sick,” one man said.

“Yeah, I’d never seen him that trim,” another responded before changing the subject.

After hearing those brief comments, I felt a sense of accomplishment. Even though our time together was short, I had a part in helping Dan feel better and achieve something important to him. Dan was not on a miserable diet, denying himself everything he wanted. He didn’t isolate himself from others to eat special food or to spend hours at a gym. In fact, it was quite the opposite. Dan unintentionally became a health advocate, a leader of sorts. People saw what he had and they wanted it, too.

Dan’s death reminded me that our time on this planet isn’t guaranteed and can be cut short for no apparent reason. As a result, I became less interested in helping people follow pitifully unpleasant diets. I focused more on encouraging people to find a peaceful balance in their journey to a healthier weight.

Purposeful living often means finding joy in self-denial. The daily satisfaction we feel when overcoming challenges, caring for ourselves, and knowing we’re an inspiration to others far outweighs the feelings we get from feeding our immediate desires. Although Dan didn’t reap all the long-term benefits of losing weight and living a longer life, the short-term effects of his efforts were just as meaningful. He lived life fully until he became sick and his weight loss was part of a broader personal transformation that made an impact on others, even me.

I began to wonder what would have happened with Dan if the cancer cells hadn’t invaded his body. Could he have kept the weight off? Or, like most others, would he have succumbed to the neurochemical, metabolic, psychological, and environmental influences that contribute to weight regain? Would those weight-gain promoting factors have been as powerful and persistent as his unstoppable cancer cells?

Even though statistics tell me Dan would probably have regained his weight, he seemed to have a perspective that could defy the odds and prevent a relapse into old patterns. My time with Dan led me to think a great deal about who succeeds long-term with weight management efforts. I began considering relapse prevention early in my work with other clients, focusing on behavior and perspectives they could sustain long-term.

Are Cars Making Us Fat?

Well it sure seemed like it in 1905. On the other hand, was it possible that fat people were more likely to buy cars?

If you will note the occupants of every automobile on any day, and will keep a record of the total number of persons and the total number of overweights, you will be astonished by the result. Are people of big bulk also above the average of prosperity and so able to enjoy the newest and most fascinating of luxuries? Or does the habit of coursing about in the automobile superinduce the fat-assimilation, which ends in ponderous preponderance of adipose?

Does getting fat improve one’s chances of owning an auto and having the leisure to use it? Does owning an auto improve one’s chances of getting fat?

—“Fat Men and Automobiles,” Editorial, September 30, 1905

10 Years Ago: Michael Phelps Becomes The Greatest Olympian

Maybe there’s something special about August 17 and sports. In 1933, Lou Gehrig played his 1,308th consecutive game. In 1969, the New York Jets and the New York Giants played each other for the first time. In 1973, Willie Mays turned a pitch from Reds leftie Don Gullett into the 660th and final home run of his peerless career. And 10 years ago today in 2008, Michael Phelps did the seemingly impossible by taking eight gold medals in a single Olympic Games.

The previous record of seven golds in a single Games had been set in 1972 by another American swimmer, Mark Spitz. Spitz was a legitimate superstar. Not only did he win seven events in ’72, he broke the world record in each one. His career gold medal total would be nine, while also notching a silver and a bronze. In addition, he would take five Pan American Games golds, 31 Amateur Athletic Union titles, and eight NCAA championships. In addition to the seven at the ’72 games, he would set another 28 world records during his career. He retired at the ripe old age of 22.

Spitz’s record was viewed as untouchable, a once in a generation, or maybe millennium, achievement. Then came Phelps. He began swimming at seven, and was the national youth record holder in the 100m butterfly by age 10. Even then, pundits were dissecting the details of what exactly made Phelps an ideal swimmer. Bob Bowman, who has coached Phelps since he turned 11, attributes some of his success to “rigid focus.” Bob Schaller, author of Michael Phelps: The Untold Story of a Champion, elaborated on another element of Phelps’s success: his relationship with Bowman. Schaller says, “The fit was perfect. Bob was made to coach Michael . . . That he and Michael were in perfect step is part of the miracle that was Michael’s career.” In fact, at the outset of the Bowman/Phelps partnership, Schaller had the chance to ask Bowman how he planned to coach the “Gangly with a capital G” young man. Bowman told him, “”There is no blueprint for this. I will either screw this up so badly that no one will forgive me, or we’ll get it right and no one will forget me.”

Others have commented on Phelps’s unusual physique, including the swimmer himself. In his 2009 book with Alan Abrahamson, No Limits: The Will to Succeed, Phelps suggests that his body type played a large role in his success in the pool. His 6’4” height, his unusually long wingspan (6’ 7”), his lean frame, and his size-14 feet would each contribute advantages in terms of start, propulsion, and movement in the water.

Going into the 2008 Games, Phelps had already notched an incredible record of achievement. He qualified for the 2000 Olympics at age 15 but finished out of the medals. At the 2001 World Championships, before turning 16, Phelps broke the 200m butterfly world record and took gold. This was a significant indicator of the future for Phelps. As Schaller says, “The 200 fly is the kingmaker in men’s swimming.” After that win, Phelps embarked on an incredible winning streak; through the 2002 Pan Pacific championships to the 2003 Worlds, he pulled down another seven golds (two in relays), four silvers (two in relays), and four world records. The 2004 Olympic Games assured the world of Phelps’s place in history; he won six golds (two in relays) and two bronzes (one in a relay).

Highlights of Phelps from the 2004 Olympic Games.

Shortly after the opening of the 2008 Olympic Games on August 8, Phelps set an Olympic record in his preliminary heat for the 400m individual medley; he subsequently won gold in the event while breaking his own brand-new record by two seconds. As the event went on, whether alone or on relay squads, Phelps dominated the competition, shattering records in every event. Phelps took his seventh gold medal of the games in the 100m butterfly.

But one more race remained. On August 17, Phelps joined teammates Brendan Hansen, Aaron Peirsol, and Jason Lezak in the pool for the 4x100m medley relay. The U.S. team was behind Japan and Australia heading into the third leg. When Phelps hit the water to do the 100m butterfly, he moved at a record-breaking pace, turning in the fastest time ever for the butterfly split in the event. When Lezak dove in, Phelps had handed him a half-second lead. It would be enough. Michael Phelps had eight gold medals in one Olympics.

Team USA compiled a highlight reel of Phelps’s eight Olympic gold medal wins in 2008.

For a normal human, that might have been enough. But for the swimmer that his teammates, competition, and commentators call “Superman,” that was simply one peak in a career of mountain ranges. He took four golds and two silvers at the 2012 Olympics, and another five golds and one silver in 2016. His World and Pan Pacific success continued, with a combined 17 further golds earned at events between 2009 and 2014, as well as another five silvers and one bronze. Phelps didn’t swim the Worlds in 2015 after being excluded from the team after being cited for DUI; however, he did compete in both the U. S. Nationals and Winter Nationals, winning three golds in each.

At the 2016 Olympic Games in Brazil, Phelps’s teammates voted for him to carry the flag of the United States at the Opening Ceremonies.

News of the Week: Academy Award Changes, Space Force, and It’s Way Too Early for Pumpkin Spice Drinks

“Oscar, Oscar, Oscar”

That line is from The Odd Couple, one of my favorite sitcoms, and I can picture Felix Unger shaking his head in disappointment and saying it to the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences after their recent announcement.

AMPAS actually made a few announcements this week, and most of them were infuriating and ridiculous. They’re going to limit the show to three hours. Now, that sounds fairly benign and logical, but one way they’re going to speed things up is to give away some of the awards during commercial breaks. Hey, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, how about taking out the dance numbers or a rambling segment or a tedious comedy bit to find more time to, you know, honor the people of your own industry on the biggest night of their lives? Am I supposed to go online to see who won during that commercial for Diet Coke, or wait for some highlights later in the show?

If that wasn’t enough to make you slap your forehead, how about this? They’re introducing a Best Popular Film category. Yup, for all those movies that might have gotten a lot of box office cash but weren’t good enough for the Best Picture category, apparently. Are they admitting that Black Panther is a “popular” film but can’t be a Best Picture nominee? It’s almost as if the people in AMPAS don’t understand movies, art, fans, network TV viewing habits, or the movie industry in general. They’re trying to appeal to more people and become more “relevant,” but I think these changes will have the opposite effect. A Best Popular Film award will be looked at as a consolation prize, which it kind of is.

Here’s video #Tsitsipas pic.twitter.com/vfQkqy4Lvk

— Joe Hackman (@joethehack) August 4, 2018

Everything is getting watered down and ruined these days, so I guess it was just a matter of time before it happened to the Oscars.

Hey, here’s a solution, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Why not just have better taste in movies? Realize that even popular films can be quality films and increase the number of films in the Best Picture category from 10 (which you already did from 5 several years ago to include more “popular” films, remember?) to 15 or even 20. Boom! Problem solved.

The Final Frontier

This is a story about the new branch of the military called Space Force, but I don’t want to get into the politics of it. Let’s talk about something more important: the logo.

Here are the choices.

Trump campaign email just went out asking people to vote for a Space Force logo. pic.twitter.com/083DG3pLdo

— Jim Dalrymple II (@Dalrymple) August 9, 2018

I like the one with the shield shape or the blue-and-white one with the rocket, because it looks like the title card from a Space Force cartoon. The red-and-white logo with the yellow ribbon? It’s okay, but it looks too much like a space logo that already exists.

Idris Elba Is the Next 007? (Probably Not!)

For years, fans of Idris Elba have been pushing for him to be the next James Bond. He has never auditioned and there’s been no real serious talk of him taking over the role, but his fans really, really want it to happen. And now it just might, because there’s a report that there are serious talks about it.

Antoine Fuqua, director of the Equalizer movies, says that Bond producer Barbara Broccoli told him that Elba would make a great Bond. Daniel Craig will be leaving the role after the next movie, so there’ll be an opening, and it looks like we can officially add Elba’s name to the ever-growing list of potential onscreen spies, along with Tom Hardy, James Norton, Tom Hiddleston, Henry Cavill, and several others.

That was the story last week. This week we found out — surprise! — Fuqua never had a conversation with Broccoli, never brought up Elba’s name, and the whole thing was made up and hyped by the web. Sorry, fans!

But there’s an obvious reason Elba won’t be the next 007 anyway. You can tell what I mean just by looking at him. It’s pretty obvious, right? I know it might be controversial to say this, but I’m going to say it anyway. Elba wouldn’t be good as James Bond because he’s … too old.

I looked at the ages of the previous Bonds, from Connery to Craig, and all of them were in their 30s or early 40s when they took on the role. Since Craig still has one more movie to go, and it won’t be released until late 2019, Elba will be close to 50 by the time he would make his first Bond movie. That means if he were to make a second movie, he’d be, what, 52 or 53? I’m 53, and that’s too old to be running around, even if Tom Cruise can still do it somehow (but he started the Mission: Impossible movies when he was 33).

Breaking News: It’s Still Summer

Look at the calendar. It’s August 17. We’re still wearing shorts, and the new TV season hasn’t started yet. But for some reason, stores and restaurants are trying to push the fall season on us already.

Case in point: Starbucks is going to start selling their seasonal favorite Pumpkin Spice Latte on August 28. Yes, that’s just what I want: to sip a hot beverage while sweating from the 90-degree temps and 70-degree dew points.

But this early appearance of pumpkin spice is still not as bad as what I saw at my local supermarket last week: a giant Halloween candy display. At this rate, Christmas decorations will be for sale just after Labor Day.

RIP Aretha Franklin, V.S. Naipaul, Morgana King, Richard H. Kline, Patricia Benoit, and Lorrie Collins

Aretha Franklin was called “the greatest singer of all time” by Rolling Stone. Starting as a gospel singer and pianist, she went on to have a ton of classic hits like “Respect,” “Natural Woman,” “Chain of Fools,” “Freeway of Love,” “Who’s Zoomin’ Who,” and her duet with George Michael, “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me).” A multiple Grammy winner, she also had a memorable role in The Blues Brothers, was the first woman inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005.

The Queen of Soul died yesterday at the age of 76.

V.S. Naipaul was an acclaimed writer of such novels as A House for Mr. Biswas, Guerrillas, and Miguel Street, along with several works of travel writing and other nonfiction. He died last week at the age of 85.

Morgana King was a veteran jazz singer and actress. She had a hit song with her version of “A Taste of Honey” and played Marlon Brando’s wife in The Godfather. She died in March at the age of 87.

Richard H. Kline was a cinematographer and camera operator who worked on such films as Camelot, Body Heat, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and the 1976 remake of King Kong, along with TV shows like The Monkees and Mr. Novak. He died last week at the age of 91.

Patricia Benoit played Wally Cox’s girlfriend on the ’50s sitcom Mr. Peepers. She died last week at the age of 91.

Lorrie Collins was the female half of the brother and sister duo the Collins Kids. They were quite popular in the ’50s and ’60s, singing such songs as “Problems Problems” and “Hoy Hoy.” Collins died last week at the age of 76.

If you’ve never heard of the Collins Kids, take a look at this video. She had a beautiful voice, and her little brother Larry was an incredibly skilled guitarist.

This Week in History

Hedy Lamarr Gets Tech Patent (August 11, 1942)

Do you use Wi-Fi or Bluetooth? You have actress Hedy Lamarr to thank for that. Lamarr and her partner, inventor George Antheil, invented the frequency-hopping technology that led to many of the gizmos we use today.

Will Rogers and Wiley Post Killed in Plane Crash (August 15, 1935)

The humorist and his close friend, aviator Wiley Post, both died when the plane Post was piloting crashed near Point Barrow, Alaska.

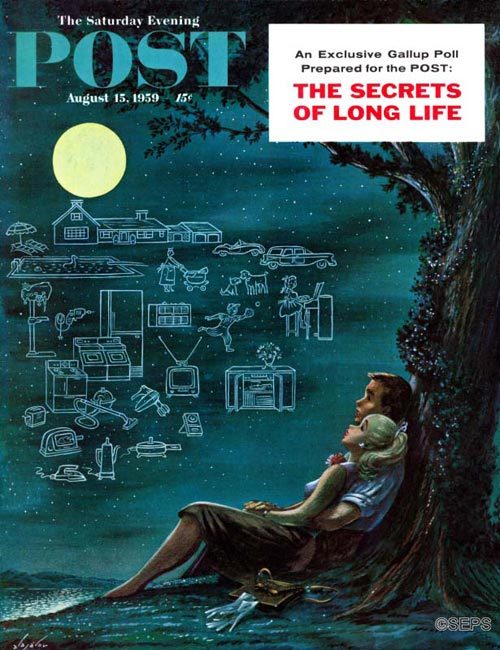

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Moonlit Future (August 15, 1959)

Moonlit Future

Moonlit Future

Constantin Alajalov

August 15, 1959

We should update this Constantin Alajálov cover and include something created with the help of Lamarr and Antheil’s invention.

Quote of the Week

“At the end of the day, it’s adults getting trophies. Why should that be taken seriously?”

—Saturday Night Live’s Colin Jost, co-host of next month’s Emmy Awards, on award shows

More Summer Desserts

I don’t eat a lot of dessert during the summer months. I’m more of a cold-weather dessert kind of guy. The only “desserts” I’ll have in the summer are ice cream and Popsicles, and even those are half taste enjoyment, half “oh my God how am I going to cool down?”

But if you’re in the mood for something fruity and refreshing to make during the next several weeks, how about this Kiwi Summer Limeade Pie, this Mini Peach Melba Ice Cream Cake, the elegant Strawberries Romanoff, or maybe an icy cold Galaxy Milkshake?

Just don’t include any pumpkin. Fall and winter will be here soon enough. There’s plenty of time.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Bad Poetry Day (August 18)

Here’s my contribution:

Roses are red

Violets are blue

Sugar is sweet

Hey, does anybody know when the new season of Game of Thrones starts?

I think in early 2019

Great, thanks

No problem

I know that’s pretty bad, but for Bad Poetry Day, it’s pretty good.

Logophile Language Puzzlers: Goofs, Grumps, and Cheese

1. In a ______ that would follow him to his dying day, Geoffrey greeted the Queen by saying, “It is my majesty, Your Honor.”

- gaff

- gaffe

- guff

2. Which type of protester is likely to be the most disruptive?

- A truculent trucker

- A taciturn attorney

- A tractable actor

3. Sherry prefers daiquiris to margaritas, asiago to mozzarella, tangerines to oranges, and fig newtons to macarons. What’s the key to Sherry’s tastes?

Answers and Explanations

1) b. gaffe

Gaffe with that final e is the word that means “a social or political blunder,” which is certainly what Geoffrey committed when he transposed the words majesty and honor.

The e-less gaff has had a number of meanings over the years, including “a cheap theater,” “a painful ordeal,” and “a deception.” But most use of the word these days comes down to hooks: metal leg spurs used in cockfights, large hooks for moving heavy fish or hanging meat to be butchered, and smaller spikes affixed to boots to aid in climbing are all different types of gaffs.

On a film set, the gaffer is the head electrician, which doesn’t seem to have an obvious connection to hooks. It’s believed, though, that the term came from the name of the person in charge of stage lighting in the early theater. Gaffers would use a gaff — a long rod with a hook on the end — to adjust overhead lights.

Guff is a completely unrelated word that simply means “nonsense,” as in, “Don’t give me any guff!”

2) a. A truculent trucker

The three words truculent, taciturn, and tractable are by no means obscure, but neither are they common.

Truculent, the correct answer, derives from a Latin word that means “savage,” and that is more or less what the word means today — though it has lost some of its fierceness. A truculent person is easy to anger and likely to argue.

Taciturn, a synonym of reticent, means “inclined to silence” — the very opposite of disruptive. You might recognize the related word tacit in there, which usually describes a type of communication without the use of words or speech, as in giving tacit consent. A taciturn attorney might be effective for creating and interpreting complex paperwork but would likely underperform in a courtroom setting.

Tractable isn’t related to tractor but is a relative of treatise. From the Latin tractare “to handle, treat,” tractable means “malleable or easily controlled.” Far from being disruptive, a tractable actor would be easy to direct.

3) Sherry likes foods that are named after places.

- The daiquiri is named after the rum-producing Cuban district of Daiquirí, whereas margaritas are named after a woman.

- Many (I daresay most) cheeses are named after the regions where they were developed, including asiago, which is a town in Italy. You’ve also probably tasted cheeses from Cheddar, England; the Gruyère district of Switzerland; Gouda, Netherlands; France’s Brie district; and Limburg, Belgium. Mozzarella, on the other hand, is from an Italian word that means “to cut off” and is etymologically related to the word mutilate.

- The mandarin oranges we call tangerines got their name from the Moroccan city of Tangier (through its French spelling, Tanger), while the word orange traces its roots to Sanskrit.

- As many people learned in the early seasons of The Big Bang Theory, fig newtons are named after the town of Newton, Massachusetts. The word macarons — describing a type of French sandwich cookie — is etymologically related to the Italian macaroni, “a stuffed pasta.”

Nudity, Fasting, and Eyelid Workouts: The Original Wellness Guru

One man you’ve never heard of is responsible for many of our notions about diet and exercise in America in the last 100 years. Though he was a largely-forgotten quirk of the turn of the century, many of his ideas about wellness have prevailed. Others — like his lifelong refusal to wear glasses — have depicted his movement as a too-natural health crusade.

Part Donald Trump, part Gwyneth Paltrow, and a tinge of Billy Graham. That was Bernarr Macfadden, the publisher, politician, and fitness fanatic born 150 years ago today.

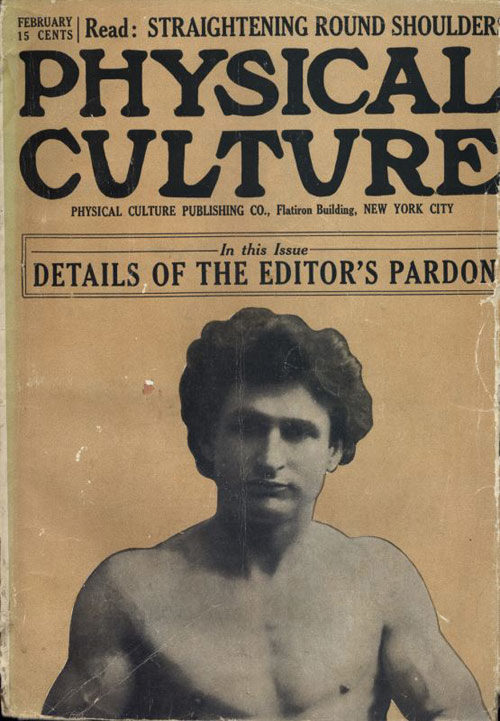

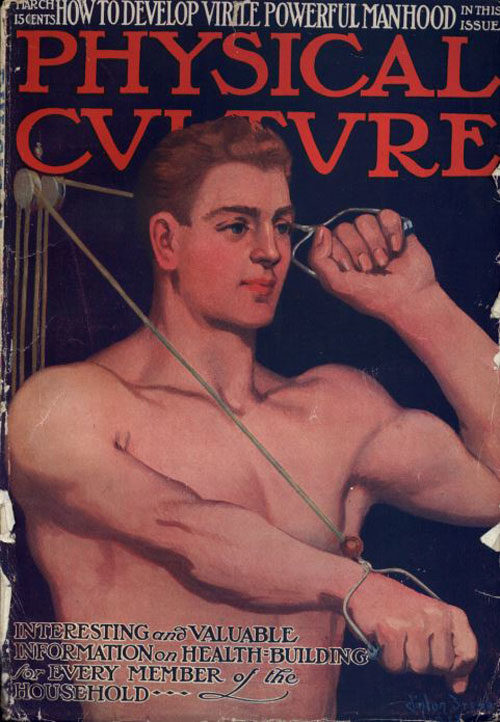

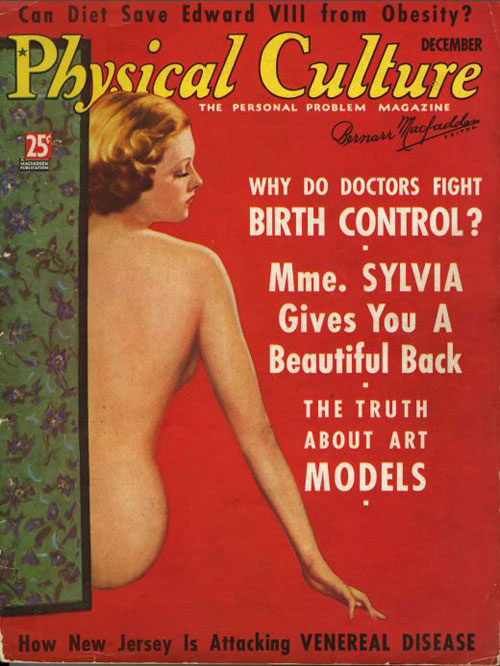

His legacy, the four-decades-published fitness magazine Physical Culture, proclaimed on its cover, “Weakness a Crime, Don’t Be a Criminal.” Early in his publishing career, Macfadden laid out the “curses of humanity” that he would fight until his last breath: prudishness, corsets, muscular inactivity, gluttony, drugs, and alcohol.

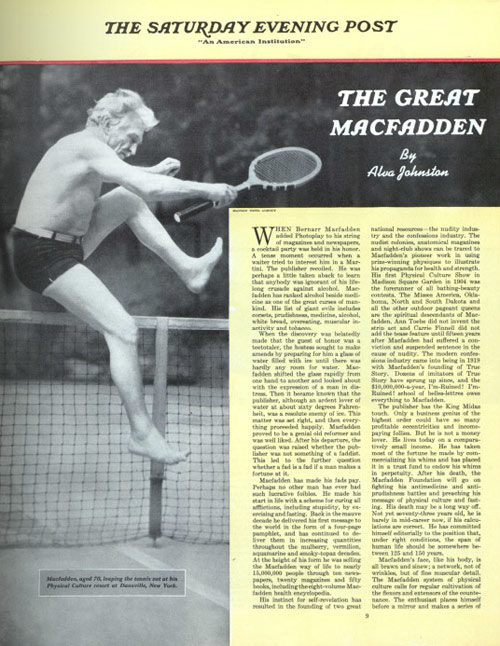

When The Saturday Evening Post profiled Macfadden, in 1941, the 72-year-old wack-of-all-trades was “all brawn and sinew” and running a magazine empire of his own with titles like True Story, Photoplay, and Liberty. It all started in 1899 with Physical Culture. The self-proclaimed “professor” of physicality started the publication in an office in Manhattan. He wrote guides for exercise and fasting and featured half-naked photographs of himself demonstrating his prescriptions.

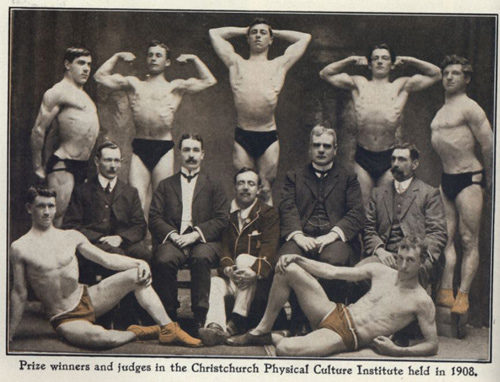

His magazine’s circulation grew to hundreds of thousands in a few years as he proselytized — often under various pen names — about vegetarianism, antivaccination, bodybuilding, and even methods for better sex. Physical Culture was marketed to men and women, and Macfadden edited the rag with a unique philosophy of confessional honesty and reader interaction. Articles on “Straightening Round Shoulders” were followed by “Beauty Culture for the Hair,” and Macfadden’s always-candid editorials railed against white flour and prudery, especially if it came in the way of educating the masses frankly about their bodies.

The obscure American icon could best be characterized by his tendency to stick to his guns, even if it involved doubling down on wild, unsubstantiated claims. “Form your opinion upon a given subject and stick to it, argue it out, fight it out,” he wrote in the first issue, “and this opinion you take up will bring in its trend a wonderful flow of thought, of ideas. Whether these be right or wrong, it does not matter a jot.” Macfadden would argue for workers’ rights, temperance, and appreciation of the nude human form. Most of all, however, he asserted that modern medicine was worthless and that a healthy diet (and some intermittent fasting) could cure any disease imaginable.

The recent migration of Americans from rural to urban surroundings generated all sorts of health complications and societal woes, and so Macfadden’s attempts to stoke a simpler, healthier lifestyle were well-received. In 1905, he opened Physical Culture City, a planned community in northern New Jersey where inhabitants could practice a lifestyle of fitness and clean eating with no red meat, no white bread, and no high-heeled shoes. The publisher had high hopes for his health utopia, but it hosted only a small, dedicated group, and nearby towns were freaked out by the village’s half-dressed, vegetarian populace.

In 1907, Macfadden was arrested for distributing “obscene, lewd, and lascivious” materials through the mail. It was a classic case of prudishness. Unlike most large publications of the time, Physical Culture prided itself in facing head-on issues of sexual health and depicting sexuality. “The exposure of ‘sexual affairs,’” Macfadden wrote, defending a recent serial, “was an essential step toward clean morals.” Still, he was sentenced to two years in the New Jersey Penitentiary and fined $2,000. He urged his readers to plead President Theodore Roosevelt, whose active lifestyle Physical Culture had commended, to commute his sentence, but it was fruitless. Instead, it was Roosevelt’s successor, hefty President Taft, who pardoned Macfadden and saved him from serving time.

The health nut took his affairs to Battle Creek, Michigan, where cereal magnates John Harvey Kellogg and C.W. Post had already built a wellness mecca. The Bernarr Macfadden Sanatorium offered hydropathy, osteopathy, milk diets, and other forms of alternative medicine in a stark mansion setting. Instead of committing to a rural planned community, clients could vacation in Macfadden’s house of Turkish baths and naturopathic doctors, and they did. Famed writer Upton Sinclair visited Macfadden’s facilities and published The Fasting Cure in 1911 in support of his friend’s homeopathic methods.

Macfadden moved the operation to Chicago after a few years and set to work finishing Macfadden’s Encyclopedia of Physical Culture, an ambitious collection of wellness knowledge in five volumes. His Encyclopedia documented many now-understood health habits and exercises far ahead of its time. Macfadden recommended whole grains, coconuts, and olive oil and condemned unnatural and processed foods. He also laid bare the fundamentals of sexual intercourse and clashed with modern understandings of microbiology. “The healthy, vigorous, athletic student here has no fear of disease; he is immune,” the Encyclopedia claims. “Unconsciously he lives in the recognition of a fact that the doctors and learned men have forgotten, that disease can find no lodgement in a healthy body.” Macfadden began a formal conflict with the medical establishment, namely the American Medical Association, that would last until the end of his long life.

In his dogged quest for a better way, Macfadden’s stubbornness and martyrdom served him well… until they didn’t. Eventually, after more obscenity trials prompted him to flee to Europe, Macfadden took up his businesses again, but over time his credibility shrank as scientific evidence countering many of his claims grew. Although he had been instrumental in making Americans interested in physical fitness (The YMCA’s attendance tripled in the first 10 years of his magazine), his bizarre advice for “natural” breathing and eyelid workouts seemed a less-viable sell toward the midcentury. Macfadden lost most of his fortune and died in relative obscurity, but his contributions to publishing (for better and for worse) and to alternative forms of medicine persist. His call for greater autonomy and responsibility for one’s wellness, however peculiar a practice may seem, is one that echoes through generations as if by human nature.

Pop Music Is Better Than Ever!

Growing up, I could never escape Del Shannon’s 1961 hit “Runaway.” On long road trips and commutes to school, the anguished refrain and keyboard solo followed me everywhere. My father, a baby boomer, couldn’t get enough of the song, and he played it compulsively in lieu of the ’90s music on the radio.

My parents had strong opinions about the then-omnipresent stylings of Britney Spears and the Backstreet Boys, let alone the rapper Ja Rule. They thought pop music had degraded over the years into an industry of predictable tunes and vapid lyrics, a common stance on the top 40 that seems to renew itself every generation. Pop music today might be cloying and formulaic, but that’s always been the case.

Some selective amnesia appears to be at work in the claims that music is getting worse. Instead of comparing every recent pop party anthem with “Good Vibrations,” perhaps we should stack them up against the Playmates’ unlistenable 1958 hit “Beep, Beep.” The Beatles were still penning meaningful and experimental lyrics in 1969, but the No. 1 song of the year was “Sugar, Sugar,” a saccharine testament to “the loveliness of loving you” by a cartoon band.

Some selective amnesia appears to be at work in the claims that music is getting worse.

Nostalgia’s ability to cloud judgment is particularly strong when it comes to music. This might be due to the physiology of the human brain. Neuroscientist Daniel Levitin explores the psychology of musical taste in his book This Is Your Brain on Music, and he cites adolescence as a formative period for acquiring musical preferences: “Part of the reason we remember songs from our teenage years is because those years were times of self-discovery, and as a consequence, they were emotionally charged; in general, we tend to remember things that have an emotional component because our amygdala and neurotransmitters act in concert to ‘tag’ the memories as something important.”

Dick Clark defended young people’s music in this magazine almost 60 years ago when pressed about the dangers of rock ’n’ roll, saying, “As we grow older our minds close in certain areas, music among them. The real truth is that you adults are more preoccupied with rock ’n’ roll than the teenagers.” The societal switch from Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby to Elvis and the Everly Brothers wasn’t a smooth one, but Clark’s American Bandstand always kept its finger on the pulse of youth culture. In the 1980s, he was booking Madonna and Run-D.M.C.

We might feel as though we’re in control of our own musical proclivities, but they’re probably thrust upon us. It’s only natural to long for the sounds of Motown or bubblegum pop if they provided the soundtrack to your first courtship. Just the same, millions of young people will eventually feel the same way about “Call Me Maybe” or “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It).” After all, does Rihanna’s “Umbrella” differ all that much from Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me”? Kelly Clarkson’s “Since U Been Gone” may as well be a modern “Red Rubber Ball.”

As a music lover, I didn’t escape indoctrination in my own tastes. Years of exposure in adolescence made me love songs like “Runaway.”

Kanye West’s “Runaway,” that is.

*“Contrariwise,” continued Tweedledee, “if it was so, it might be; and if it were so, it would be; but as it isn’t, it ain’t. That’s logic.”

—Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll

This article is an expanded version of the interview that appears in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Fill ’Er Up? Modern Gas Stations Have No Soul

I once loved the distinctive fragrance of gas stations. These days, regrettably, it is but a faint memory. In its place, at thousands of sleek stations across America, you’re likely to inhale an incongruous noseful of car-wash detergent, hot ham hoagies, and beer. Blech! I favor the intoxicating aroma of grease and engine lubricants.

So, you conclude, my wee brain was rotted by excessive exposure to petrol vapors? Possibly. But the fact of the matter is that the modern station — so clean and anodyne and barely about gasoline at all — is a soulless thing.

Most newer ones are little more than appendages to convenience stores and are illuminated, you might be tempted to guess, by the same folks who light sports stadiums. They are focused on fueling drivers; the pumps and cars are an afterthought. That’s not entirely a horrible development. It’s a sweet moment indeed when you can pull off the road, wash up in a restroom, and grab some decent food.

Still, do you recall those iconic little stations patterned after colonial and English cottages, meant to mimic “a home away from home”? Uniformed assistants would greet you, the weary traveler, offering free road maps, a comfy chair if needed, and service bays in which friendly techs could fiddle with your ailing vehicle. Pretty much ancient history, all of that. (Secretly, don’t you wish you’d filched a sign from a White Eagle or Wofford station? The auction value of gas station memorabilia — especially antique pumps — can leverage you into a new electric vehicle, which, among other things, would mean never having to wait in a gas queue again.)

I conclude that most of today’s stations are essentially a contemporary iteration of the old general store, except they don’t sell feed for horses and everything occurs really fast. (According to industry stats, customers, on average, linger just 3 minutes and 33 seconds in these mini marts.) They compete against sandwich shops, grocers, pharmacies, car washes, souvenir stands, banks, and coffee joints. Their best-seller is soda. (In my neighborhood, some of the finest pizza around can be had at a small Shell station, and I’m not proud of that.)

Particularly disappointing about modern filling stations is that few remain in the repair business. Not much money in that — nor in filling cars’ tanks, for that matter. A five-cents-per-gallon profit is average. Consequently, owners have sought new ways to assure repeat business. One lesson most have learned is that a sparkling restroom is paramount. There’s even a smartphone app that directs drivers to the cleanest bathrooms along our major thoroughfares. (For the record, QuikTrip and Wawa stores are tops, nationally.)

“One in five people uses the restroom when they stop to buy gas,” I was told by Jeff Lenard, vice president of strategic initiatives at the National Association of Convenience Stores. “It’s really the front-door experience. If it’s a bad experience, no one will immediately say, ‘Let’s go get a sandwich now!’” No argument there.

Lenard is a veritable guru of gas stations. It was he who mentioned to me offhand that Col. Harland Sanders owned several large operations back in the ’50s. They eventually closed, but Sanders heeded the advice of loyal customers who urged him to “sell more of that chicken.” Also, interestingly, Frank Lloyd Wright had designed a few stations for the Buffalo area, Lenard said, but they never got built. Too architecturally challenging.

So, what’s next for American gas stations? I asked Lenard if the coming wave of electric cars will ding the business. Not likely, he said. “Forty million people a day fill up at gas pumps. Demand is still light for charging stations.” Overall, business remains strong, Lenard said, “but like with air travel, the glamour days are gone.”

In the last issue, Neuhaus wrote about astrology’s return and sudden rise in popularity.

This article is featured in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: 5 Quirky Facts about Rotary Phones

A few decades ago, telephones came one per house. They hung on the kitchen wall or perched on a hallway table. It seems quaint now, but that rotary-dial phone was a family’s lifeline to the outside world. Here are a few reasons people loved – or loathed – their rotary phones.

See more History Minute videos.

North Country Girl: Chapter 65 — “You’re Fired”

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Through persistence, a lost diamond bracelet, and my best good fairy gift, my incredible luck, I was a real live magazine editor (well, assistant editor), at Viva, a magazine that suffered from multiple-personality syndrome and was losing boatloads of money every month.

The fact that Viva was such as mishmash of a magazine was not due to an incompetent staff. Everyone did their job well; we just had completely different ideas of what that job was.

I thought my job was to get as much free stuff as possible, through mentions in my frivolous little section, “Tattler,” volunteering to model products myself. I was photographed posing in a racing jacket that in real life made me look as if I were swaddled in Reynolds Wrap and running a device over my face that promised smoother skin, and was as effective as a wood sander in removing my epidermis.

The one thing I did take seriously was my responsibility to my first friend at Viva, the down-trodden managing editor, Debby, who was tasked with getting the magazine to the printers. I made sure that my copy had left my typewriter and was at the art department well before it was due.

The person who did the best job was Viva’s extraordinarily talented art director, Rowan Johnson. Through a fog of drink and drugs, and always past deadline, Rowan created stunningly beautiful covers for Viva. Unfortunately, at newsstands in most parts of the country Viva was still thought of as the penis magazine. Rowan’s ground-breaking work was doomed to be wrapped in brown paper and stuck under the counter with Hustler and Club magazines.

Most of the Viva editorial staff regarded their job as ignoring the penises of the past and the still-present soft porn and erotica and transform Viva into a competitor of Ms. and Mother Jones. Between the fashion sections featuring $1,000 dresses and the photos of nude smooching couples were articles such as “Daughters of the Earth: The Difficult Lives of Indian Women,” “Jane Fonda: An American Revolutionary,” “A Guide to Abortion in America,” and “The Facts about Wife Abuse.”

What Bob Guccione, who was footing the bill for this cockamamie magazine, thought of Viva was irrelevant, until suddenly it wasn’t. Guccione happened to pick up an issue of Viva whose lead story was a 5,000-word profile of La Pasionaria, a woman who had fought against Franco during the Spanish Civil War and was now an infamous Basque separatist.

Bob had taken one look at the wrinkle-faced, white-haired La Pasionaria, photographed in the style of Margaret Bourke-White, and yelled “What the f— is this?” Even if they were brave enough to attempt it, no one around him could have explained to Bob why there was a full-page photo of an 83-year-old Communist wrapped in a black serape in a magazine aimed at young, sexy, fashion-forward sophisticates.

The era of the leftist, feminist attitude of Viva was over. Kathy decided that what Viva needed was an editor who could claw it out of the red, someone to woo advertisers into a magazine that now had a reputation for being not only X-rated but radically left-wing.

Our new editor was Helen Irwin, whose previous job was selling ad space in Tennis magazine. She looked the part — of a tennis player, not an editor. She was Amazonian, tall, blonde, sinewy, tan — I don’t think anyone would have been surprised if she had bounded into the office wearing tennis whites. Helen’s job at Tennis must have been easy: the magazine ran articles on tennis rackets and she sold ads to companies that made tennis rackets.

Helen’s mission was to turn Viva into a “consumer” magazine; at her first editorial meeting she said, “I want more beauty features. That will bring in Revlon and Clairol. Get someone to write an article on setting up a home bar. Check with the ad department to see what liquor companies to mention. And we’re going to do a guide to sports equipment. I have a meeting with Wilson this week.”

Viva had a new imaginary reader: A Babe Didrikson with a fondness for cosmetics, booze, and designer clothes, who was also an adventurous sexual libertine (the last item being the infallible Viva gospel according to Miss Keeton).

Several editors defected after this meeting. My scruples allowed me to stay. I liked my job. I liked getting free stuff and dining out on someone else’s dime. Just that week I had eaten blini and caviar at The Russian Tea Room, washed down with a disgusting shot of newly introduced, vile, and short-lived USA, America’s First Potato Vodka; and I had been invited to a Pernod-sponsored dinner at the swanky French restaurant, Le Perigord, on Park Avenue, where every course, from appetizers to dessert, tasted like Good & Plentys.

Of the surviving Viva editorial staff, I was the first to work with Helen, as I always delivered my copy to the art department well before deadline. Usually my bits of fluff were relegated to the assistant art director, but I was nervous about working with Big Blonde; I had begged Rowan, Viva’s genius art director, to do the layout for my “Tattler” section and to let me review it early in the day, before the bar across the street opened.

Rowan phoned me. “Come take a look, Gay.” I hurried down to the art department, made complimentary noises about Rowan’s work, and promised to never ask him again. I had just finished initialling my “GH-OK” on each page when Helen strode into the art department, swinging an imaginary racket. Rowan cowered as she approached; Helen had a good five inches and thirty pounds on him. With a powerful fronthand Helen slapped Rowan on the back and bellowed, “How you doing there, guy?” almost knocking him into the light table.

Rowan did not respond to Helen’s hearty hail fellow well met; he lit a fresh cigarette from the half-smoked one in his mouth and retreated to his office to find something to recuperate with. I handed Helen my pages of the magazine so she could approve my “Tattler” section and Rowan could get back to serious substance abuse.

Helen flipped slowly through the layouts. She started out obviously upset, and as she went on her eyebrows got higher and her jaw tighter. Helen put the papers down, whirled at me, and said, “You must be the most incompetent person I have ever met.”

I was busted. The editor had no clothes. This sport/sales woman had discovered that I was a fraud. It was like a bad dream, hearing someone vocalize my deepest fear, that I was an imposter, with no claim to being any kind of editor or writer or even a decent secretary. After all, I was only hired in the first place because someone wanted to go to bed with me.

I was so incompetent that when Helen asked me, in the chastising tone of a third grade teacher, “Do you know what you have done?” I didn’t have a clue.

Helen shook the pages at me. “Look again.”

I did and I was still baffled. Helen gave me the glare my mother used to when I claimed I didn’t know how to dry dishes. Helen grabbed the layout from me and started reading aloud. What came out was complete goobledegook:

“Loren ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In sit amet imperdiet turpis, a molestie elit. This is what you just okayed to run in the magazine,” she scolded.

The oboli dropped. Art directors, back in the pre-computer era, used what was known as Greek type, though it was actually Latin, as place holders for real copy. Greek type came in sheets so it could be cut up, laid out, rejected, re-cut, re-laid out, and eventually pasted down. Once the layout was approved, the actual text replaced the Greek type, the editor cutting or adding words to make it fit.

My brain was still cross-wired with panic, self-recrimination, and guilt and could not stop my mouth from blurting out “Are you stupid?” I may have added the f-word.

I had been working with Greek type since I picked up my first girl set at Oui, but the new editor of Viva didn’t even know what it was? Rowan, yanked from his office sanctuary and opium den, sobered up enough to explain Greek type to Helen. I stomped back to my cubicle, rolling my eyes all the way.

The next day Helen called me into her office.

“You do not fit in with my plans for Viva,” she said and held out a check.

I was convinced that Helen could not possibly be speaking to me but to someone else who had snuck in behind me; I almost looked over my shoulder. Why was I here with this person who was being fired? The check Helen was waving in her hand had nothing to do with me.

Helen had completely flummoxed me twice in two days. But this time my brain synced up to my mouth. I said, “You’re firing me? You can’t fire me.”

I left Helen and went straight to Miss Keeton, who saw my crazed state, pushed me into her office, and shut the door. There was nothing to be done but to tell the truth, and I knew Rowan would back me up.

“I should not have said what I did, Miss Keeton. I love my job and want to be part of the new Viva.” Whatever that turned out to be. “I don’t deserve to be fired.”

I probably did deserve to be fired, but Helen Irwin, basking in her new position of power, had not bothered to let Kathy Keeton know that she was making a staff change. Her mistake trumped mine.

Miss Keeton sighed and said, “I’ll see what I can do, Gay.” I was dismissed and spent the rest of the day drinking alone at P.J. Clarke’s. I did not want to go home to my struggling artist boyfriend, Michael, and have to explain what I was doing at our apartment in the middle of the day or where next month’s rent was coming from.

I received my third and final wish from the magic diamond bracelet: to get a byline in the magazine, to be transformed from secretary to editor, and now, to keep my job.

Helen could fire me from Viva, but thanks to Miss Keeton, not from the company. As there was no way Helen was going to have someone on her staff who had publicly cursed her out, I was dispatched by Kathy over to Penthouse as editorial assistant, a demotion in title but a promotion from a rapidly failing magazine (Viva would close within the year) to one that made millions of dollars every month, the best-selling men’s magazine in America.

I gathered up my things and moved across the office. Two flimsy grey fabric-covered boards were erected for me in the back of a big room where three secretaries sat. Tucked away out of sight, I felt as if I had been smuggled into the Penthouse editorial department.

Defending Freedom of Speech — Even When You Hate What Some People Wish to Say

In a 1943 decision, the Supreme Court held that Americans weren’t required to pledge allegiance to or salute the flag. The editors lauded the opinion on behalf of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and all Americans, whose loyalty cannot be commanded.

The principles of Jehovah’s Witnesses can be pretty annoying to the majority of citizens. They insist on propagating their beliefs at the most inconvenient times and places, and they make no concessions to the sensibilities of the majority. To our way of thinking, this makes all the more impressive the action of the court, taken in time of war, when hysteria can so easily be directed toward eccentric minorities.

The majesty of the flag will not suffer because it has been permitted to remain the symbol of a willing loyalty. The flag, which symbolizes our hard-won privileges, waves more proudly than before over the land of the free. Love of country is not in danger. It springs, to quote Justice Douglas, “from willing hearts and free minds.”

—“Score for Freedom, No. 2,” Editorial, July 10, 1943

This article is featured in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Julia Child: Cut-Up in the Kitchen

Originally published August 8, 1964

In New York’s Greenwich Village, a coterie of avant-garde painters and musicians gathers each week in a loft to watch The French Chef, convinced that Mrs. Child is far more diverting than any professional comedian. At first they assumed that she was doing a parody of the traditional cooking program, but even the discovery that she was playing it straight failed to dull their enthusiasm.

In the garrets around Washington Square, the introduction to the lesson on artichokes stands as the authoritative example of Mrs. Child’s humor and style. The scene opened on an artichoke boiling in a pot of water and shrouded by a piece of cheesecloth. Mrs. Child, looming suddenly into view, lifted the cheesecloth with heavy tweezers and inquired, “What’s cooking under this gossamer veil? Why here’s a great big, bad artichoke, and some people are afraid of it.”

Of the other two remarks still quoted in the coffeehouses, the first concerned a chicken in a frying pan. “We just leave it there,” said Mrs. Child, “letting it make simple little cooking noises.” The second had to do with crêpes suzette. As she put a match to it, she said, “You must be careful not to set your hair on fire.”

In the less-threatening circumstances of her own home in Cambridge, Mrs. Child reveals herself as an even more engaging woman than she seems on television. She stands over 6 feet tall (her dress size she describes as “stately”), her eyes are grayish green, her hair brown, and her complexion freckled.

Mrs. Child’s premise is that French cooking is “neither so long, so rich, nor so complicated” that it cannot be accomplished by anybody willing to take the necessary trouble. “It doesn’t have to be fancy,” she says, “but you have to care about what you buy; squeeze the tomatoes, shun the bottled salad dressing — that sort of thing.

“Most of the food in this country is frightful,” she said. “It’s because people don’t care enough, just a matter of bad habits.”

Each of her cooking lessons has about it the uncertainty of a reckless adventure. She has a way of losing things — either the butter, or the carrots she so carefully chopped into small cubes, or, on one memorable occasion, a pot of cauliflower. Sometimes she forgets to put the seasoning in the ragout; sometimes she drops a turkey in the sink.

But to Mrs. Child, these slight misfortunes are of no importance, merely the expected hazards of a long and dirty war. Smiling and undismayed, secure in the knowledge that her cause is just, she bashes on, perhaps pausing to remark, as she did once of a potato pancake spilled on a sideboard, “If this happens, just scoop it back into the pan; remember that you are alone in the kitchen and nobody can see you.”

When, at the end of the program, she at last brings the finished dish to the table, she does so with an air of delighted surprise, pleased to announce that once again the forces of art and reason have triumphed over primeval chaos.

—“Everybody’s in the Kitchen with Julia” by Lewis Lapham, August 8, 1964

This article is featured in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Killing Ourselves to Live Longer

The pressure most of us feel to remain fit, slim, and in control of one’s body does not end with old age — in fact, it only grows more insistent. Friends, family members, and doctors start nagging the aging person to join a gym, “eat healthy,” or, at the very least, go for daily walks. You may have imagined a reclining chair or a hammock awaiting you after decades of stress and, in the case of manual laborers, physical exertion. But no, your future more likely holds a treadmill and a lat pull, at least if you can afford to access these devices. One of the bossier self-help books for seniors commands:

Exercise six days a week for the rest of your life. Sorry, but that’s it. No negotiations. No give. No excuses. Six days, serious exercise, until you die.

The reason for this draconian regime is that “once you pass the age of 50, exercise is no longer optional. You have to exercise or get old.” You may have retired from paid work, but you have a new job: going to the gym. “Think of it as a great job, which it is.”

People over 55 are now the fastest-growing demographic for gym membership. A few gyms, like the Silver Sneakers chain, deliberately target the elderly, in some cases even to the point of discouraging those who are younger — on the theory that older folks don’t want to be intimidated by meatballs or spandexed sylphs. If the mere presence of white-haired gym-goers isn’t enough to repel the young, some gyms don’t offer free weights, partly because the sound of falling weights is supposedly annoying to older people and partly because older people, who are more likely to use exercise machines, may see them as a reproach. In the mixed-age gym I go to, membership tilts toward the over-50 crowd, where “exercise is no longer optional.” The more dedicated may use the gym as only part of their fitness regimen; they run in the morning or bike several miles to get there. Mark, a 58-year-old white-collar worker, does a 6 a.m. workout before going to work, then another one after work. His goal? “To keep going.” The price of survival is endless toil.

For an exemplar of healthy aging, we are often referred to Jeanne Louise Calment, a Frenchwoman who died in 1997 at the age of 122 — the longest confirmed human life span. Calment never worked in her life, but it could be said she “worked out.” While he was still alive, she and her wealthy husband enjoyed tennis, swimming, fencing, hunting, and mountaineering. She took up fencing when she was 85, and even at 111, when she was in a nursing home, started the morning with gymnastics performed in her wheelchair.

Anyone looking for dietary tips will be disappointed; she liked beef, fried foods, chocolates, and pound cake. Unthinkably, by today’s standards, she smoked cigarettes and sometimes cigars, though antismoking advocates should be relieved to know that she suffered from a persistent cough in her final years.

This is “successful aging,” which, except for the huge investment of time it can require, is almost indistinguishable from not aging at all.

From the book Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer, Copyright © 2018 by Barbara Ehrenreich, published by Hachette Book Group.

This is an excerpt from an an article that appears in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

“Petticoat Empire” by Edith Embury

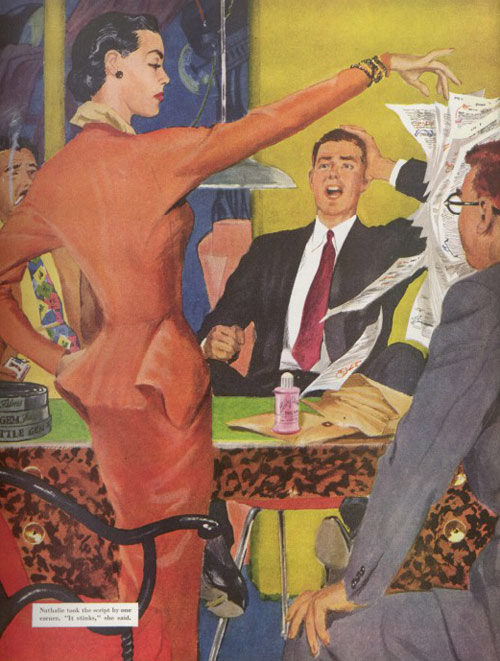

Summer is for steamy romance. Our new series of classic fiction from the 1940s and ’50s features sexy intrigue from the archives for all of your beach reading needs. In “Petticoat Empire,” an advertising producer is over budget and under staffed, and she’s falling for a know-it-all writer. This 1951 short story offers a glimpse into the glamorous atmosphere of midcentury advertising, romantic cajoling and all.

Little Gem Advertising Film Productions had one rebuilt 35-millimeter camera and a 30-by-50 portion of warehouse space called the studio. Little Gem also had two motion-picture directors who doubled as cameramen, and a producer. The producer was a brunette with bright brown eyes, and her name was Nathalie Wyman.

Nathalie was no secondhand rebuilt. She was young and beautiful. What you could see of Nathalie was gorgeous and what you couldn’t was provocatively covered by Hattie, Nettie and Sophie.

Men made passes at Nathalie which she promptly passed by. Her master plan for traveling the road to success permitted no dalliance along seductive bypaths. Men were things to think about later after she had been called to Hollywood to produce extravaganzas in color. She expected, of course, when she got around to it, to take her pick from a whole herd of rich, dynamic captains of industry.

In the meantime she looked in her office mirrors and told herself she was the best producer in the less glamorous side of motion pictures. Her production meetings went off like clockwork. Her shooting schedules never sagged into overtime. From script to negative to customer — one Little Gem production — all under budget.

Nathalie’s pet customer was Babyskin Lotion, and so the 10 o’clock production meeting for Babyskin Theater Ad 27, with Nathalie Wyman presiding, should have gone off in the usual routine fashion.

Director Al Kolski sat midway of the desk and read the script aloud. Carol Lee, secretary to Nathalie and plain stenographer to the rest of the staff, hung her pencil in the air and waited for Nathalie’s comments. Doug Wilson, promoted to head writer since the hiring of an assistant, blinked and chain smoked.

His new assistant, Joe Frane, sat with his chair tipped back against the wall. Joe’s eyes were closed. His complete disregard for the presence of the producer was a sizzling fuse under his tilted chair. The fuse was attached.

Her annoyance mounting by the minute, Nathalie stared holes in the wall over Joe Frane’s head. Insolent boor. What was it Wilson had told her about him? Newspaper reporter who’d worked on films in the Navy. Single, in his late twenties. Writers! Every day, litters of them could be crammed into weighted sacks and dropped in the river and no one would ever ask what happened.

A strange word jerked her thoughts into line. Uxorious. What did that mean? Ferd Zwinnick, sales-promotion manager for Babyskin, wouldn’t understand it. He’d say, “If I don’t understand it, the audience won’t either.”

Kolski finished reading and passed the script to Nathalie. Joe’s chair came down with a thud.

“Damn good,” Joe said, sliding to his spine. “Thought I’d gone stale on it, but it’s better than I guessed.”

Wilson darted his assistant an invisible ray designed to wither, but Joe, lost in admiration of his opus, remained healthfully ignorant. Kolski reverently turned his face to Mecca, and Wilson followed suit.

Nathalie took the script by one corner, holding it away from her, shoulder high, like something lifted from a sewer. She wheeled from her chair and tossed it toward the wastebasket. In a coldly regal voice she exploded her bomb, “It stinks.”

Joe hit the floor. Six feet of him seemed to lean over the table all at once. Nathalie braced herself for a bellow, but what she heard was as quiet and smooth as steel drawn over velvet. He had the bluest eyes she had ever seen. “In just what spots would you say the odor is offensive?”

“I don’t have to be specific, Mr. — ah — Frame.” There was a definite accent on the “I.”

“Frane. But call me Joe; it’s chummier.”

Nathalie ignored the offer. “I want another script immediately, Wilson. We’ll have to switch schedules, shoot Daisy Food Choppers tomorrow and put Babyskin over to the day after. Mr. Zwinnick is arriving sometime today, but I’ll have to stall him off. And, Wilson, you’d better do the rewrite yourself, so the formula will be followed.”

“Formula!” Joe’s voice bled with anguish. “That’s the trouble with your Babyskin ads. I ran the whole 26 yesterday, and every one is five minutes of commercial blah. People don’t talk that way. Not real people.”

Nathalie knew the signs. In another minute he’d reach the shouting point. Deftly she applied the needle. “At Little Gem we give our customers what they want. That’s Lesson One, Mr. Frane.”

“Even if they want castor oil straight, I suppose. Look, Nat. Did you ever try giving Zwinnick some orange juice along with it?”

“I am not paid to waste my time arguing with writers!” Her face was getting hot. “If you can’t understand an advertising formula, you don’t belong in the business. The script is no good. Wilson knows it. So does Kolski.”

As one man, Wilson and Kolski nodded agreement.

Joe looked at them all in turn. Then he smiled and bowed from the waist.

“Thanks, Miss Wyman,” he purred. “Thanks for the unbiased hearing. Even as a puppet show it wasn’t worth the price of admission.”

He went out. Nathalie stomped to a window and stood there, her back to the room. The others slowly pushed their chairs aside and stole away.

She sat down at her desk and put her face in her hands. She had lost her temper, and so she had lost the battle. A new script would be written, yes, but he’d made her look petty and ridiculous with that easy way of his. He’d drawn her in and then he’d slapped her down with a bow and a Cheesy-cat grin. Puppets! Naturally, out of courtesy, Wilson and Kolski always waited for her opinion.

She got up and looked in the mirror between the windows. Not a curl was out of place. She consulted the full-length mirror on the powder room door. She pulled down her girdle and straightened the topaz clip on her lapel. No one at Little Gem had ever called her “Nat.” “Look, Nat.” There was an earnest warmth in the way he’d said it. Sort of made you glow inside, even if it didn’t mean anything personal. Maybe he would quit. Well, so what? The script wasn’t any good. But if Wilson made a fuss she’d better be sure of her facts.

She pulled the script from the basket and returned to her desk. She read it over, word for word, and reluctantly conceded she had missed a few things while working herself into a state over Frane’s lackadaisical attitude. Too many scenes, though. He must have thought Zwinnick was made of money.

Look, Nat. Go on and patch it up. The guy knows how to write. Tell him why you can’t produce it. Tell him the truth.

She put on new lips and went upstairs, where she never went. Her own office was draped and carpeted, and people came to her. She never went to anyone as she was going now to Joe Frane.

The staff room was a barren waste without benefit of partitions. A few battered desks were pushed into various positions to catch the light. Carol’s was in the middle, and there she sat, pounding her typewriter and answering telephones. Wilson was out, and Nathalie wondered if he was already on the prowl for a new assistant. The farthest desk held the lower extremities of Joe Frane. He was on his spine again, his hands clasped behind his head.

She found a kitchen chair and dragged it bumpety-bump across the floor. Joe heard the alarm and unfolded.

She sat on the edge of the chair and handed him the script. “I read this over after you left and It’s all right — it’s pretty good, in fact, but I — that is, we — ” She lost herself in the blue intentness of his eyes.

“But you can’t produce it,” he finished. “Seems to me I heard that before.”

“You’re not to take personally anything that was said downstairs. We give our opinions, but they’re impersonal, you understand.” His hair was brown. He might have been a towhead when he was a kid. He had big-knuckled, outdoor hands — not white, womanish hands as so many writers had.

“Impersonal,” he said. “I see.”

“It keeps us from getting our personalities mixed up with our work. I thought if I explained our policy, you wouldn’t do anything hasty. I mean — ”

“That topaz clip you’re wearing.”

Her hand went to the clip. “I was going to say that by keeping everything impersonal we — ”

“It matches your eyes. Is it Brazilian?”

“I don’t know. I bought it at an auction. Is that good — Brazilian?”

“Very good. Citrine quartz doesn’t have that lively depth of color.”

She was silent before this vast display of knowledge. If he knew stones, there was no telling what other fascinating things were stored away in his mind.

He said, “Let’s forget the formula business. What’s the real reason?”

“The formula is not acceptable,” she snapped. Darn him anyway.

“It wouldn’t be budget, would it?”

He had drawn her in again. Budget was the truth, the truth she had come to tell him, only he’d got her off on a detour by way of Brazil. She slapped the desk. “Yes, if you want to know! I’ve never gone over budget on any picture yet, and I don’t intend to. We can bill 500 dollars for Ad 27, and that’s all. Your version would double that amount.”

“Babyskin spends a million a year on advertising. If you ask me, somebody’s selling you short.”

“I’m not asking you! I’m very happy Mr. Zwinnick favors us at all.”

“Five hundred peanuts. And I thought this business was going to be fun.”

A phone rang. Carol answered it and covered the mouthpiece with her hand. “Miss Wyman, Mr. Zwinnick is here, and he’s down on the stage. He’s getting in everybody’s hair and they want to know what to do with him.”

Nathalie looked from Carol to Joe and her eyes sparked with inspiration. Pulling Zwinnick away from his beloved playthings was a man-sized job. Zwinnick wouldn’t stand for any trumped-up nonsense.

She said, her voice dripping honey, “Mr. Frane, get Mr. Zwinnick out of the studio and into my office, will you?”

Joe ambled toward the door. “You want him vertical or horizontal?”

“Vertical, if you please. Little Gem doesn’t insult its customers.”

Smiling as she had not smiled that morning, she stopped to dictate a memo to Carol. When she returned to her office, Zwinnick was sitting beside her desk, rosy and cherubic and meek as a lamb. Joe was nowhere to be seen.

She had dinner with Zwinnick at his favorite bar. Zwinnick talked. He liked to talk and Nathalie played a customer’s game. While he post-mortemed the speech he had made to the Flat Rock Sales Supervisors Club during the previous week, she nodded at appropriate intervals.

She hadn’t seen Joe all afternoon. Maybe he’d gone home to work on another script. Maybe he’d quit. Or been hit by a car while crossing a street. He might even now be lying in the police hospital, writhing in agony….

There he was, striding into the bar! And he was all in one long piece. He waved to a couple of fellows and went over to stand between them. One of the fellows was Art Matthews, owner of Artcraft Film. Was Art offering him a job?

She tried some frantic telepathy. Don’t take it, Joe. Don’t listen to him. Loyalty to Little Gem is our first principle. Or loyalty to the customer . . . or something. I’m your conscience, Joe. Turn around, so you’ll know I’m here.

But the air waves were clogged with static and Zwinnick. Joe finished his drink, gave Art a friendly pat and disappeared.

Zwinnick ordered dessert — chocolate ice cream roll laced with marshmallow.

“And before I give that speech again,” he said, “I might even improve it a little. Last night I had a stomachache and couldn’t sleep, so I got to thinking. Listen to this, Nathalie. ‘Salesmen are made, not born.’ How’s that for a punch title?”

“Wonderful,” Nathalie said. “I think it’s just wonderful.”

She went home early, begging off from the movie he wanted to see. He would talk all through the picture. And later, over midnight coffee, he would tell her again that a widower’s life was a mighty lonely one.

She paced her apartment. She looked up “uxorious” in the dictionary and wished she hadn’t. She took a shower, shined her hair with a hundred strokes and got into bed. She tossed and turned and punched her pillow into assorted lumps. She was in love. It wasn’t romantic. It wasn’t even mutual. She didn’t want a writer and she didn’t want to live on a writer’s salary. She wanted her career, her annual bonus, and Hollywood and a captain of industry. And she wanted Joe Frane. She felt as if she’d been hit by a dump truck.

With a day to kill before Ad 27 got underway, Ferd Zwinnick tried to murder it for everyone but himself. He planted a chair in front of the Daisy Food Chopper set and ordered a light standard moved back six inches. Kolski, getting ready to move it forward, sweated and wiped his face. He ordered the standard moved back, and when Zwinnick bent over to pick some lint off his trousers, he signaled to have it moved forward a couple of feet.

Zwinnick looked up and said, “That’s better.”

“Patsy ready?” Kolski asked.

Patsy entered the set in a calico house coat.

“Quiet, everybody,” Kolski said. “Voice recording.”

The silence bell sounded. The camera ground. Patsy plugged in her Daisy and began feeding it scraps of raw meat from a platter. She hummed a tune and looked starry-eyed as hamburger rolled into a bowl.

Zwinnick sneezed.

“Cut!” Kolski bawled. He put his hands on his hips and glared at Zwinnick.

“Sorry,” Zwinnick said. “I must have caught a cold last night.”

Kolski beckoned his chore boy. “Get that guy Frane,” he muttered. “He pulled that big baboon out of here yesterday, and he better do it now. I got to swallow him tomorrow, but today I’m going to have a holiday.”

Nathalie walked onto the set, a script in her hand. She looked at Patsy, did a double take and marched over to Kolski.

“Where’s Rita?” she asked. “I thought we agreed on Rita.”

“Been hitting the gin and couldn’t make it.”

“The approved script calls for the motherly type.”

“I know, but we decided to knock it out and make it a bride.”

Nathalie stamped her foot. Who did they think they were, assuming the producer’s prerogatives? More than once she had canceled shooting on less provocation.

“Cancel the schedule,” she ordered. “Get Wilson and come into my office.”

Joe Frane went by. Kolski said, “Hi, Joe. Good girl you got, that Patsy.”

Nathalie followed Joe with doelike eyes. He hadn’t quit. He was right on the job.

Kolski’s words broke through her adoration. She whirled angrily. “Joe got this girl Patsy? Where?”

“I don’t know, but she’s something, isn’t she?”

Something was right. She was the cutest model who had walked into the Little Gem studio in months . . . and Joe Frane had got her! His girlfriend, of course. His heavy date. Who else would be so accommodating in an emergency?