This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the March/April 2011 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

The war fought by Americans against Americans on American soil, for four excruciating years is still the deadliest war in American history. More than 600,000 fighting men were killed, some of them brothers in arms against brothers, and uncounted civilians died. It was a war over nothing less than whether to preserve or end the United States of America.

Most armed conflicts are about territory. This one was about ideas. The war would put an end to slavery. It would also create, if painfully, a cohesive single republic — more united than it had ever been before. In fact, the Civil War transformed the United States from a plural noun to a singular one. Before, you would say the United States “are.” Ever since the war, we say the United States “is.”

War became inevitable in December 1860, when South Carolina declared that it would no longer be a part of the United States. Abraham Lincoln had just been elected president, and the Southern states were convinced he would immediately outlaw slavery, on which their economy depended. They resolved to leave the Union rather than have their way of life overthrown. In February 1861, South Carolina and five other states announced that they were now the Confederate States of America. U.S. Army forces had to retreat to Fort Sumter, a granite fortification in the harbor of Charleston. When the forces refused to leave Fort Sumter, state militiamen waited, wore them down by preventing supplies from getting through, and then opened artillery fire on them. The bombardment lasted for 33 hours, until 4,000 shots and shells set Fort Sumter on fire. Finally, the U.S. flag came down, and the Fort surrendered.

No one imagined how long and devastating the war would be. The first big battle was fought in July 1861, at Bull Run in Virginia, near Washington, D.C., where Union troops attacked Confederate forces in hopes of putting a quick end to the conflict. The Confederates withstood the assault and then counterattacked, and the battle turned into a rout of the Union forces. Many hundreds on both sides were killed, and thousands more were injured. Americans began to see what a long nightmare they had trapped themselves in.

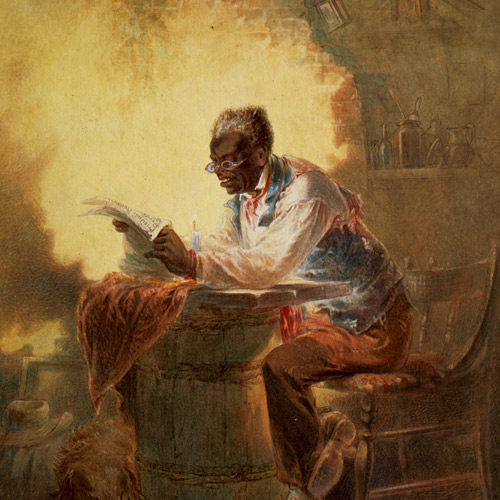

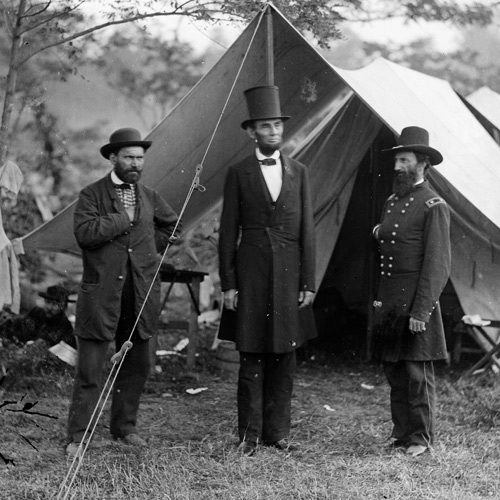

For more than a year after that, Southern troops won victory after victory under a brilliant general, Robert E. Lee, while Lincoln was disappointed by one irresolute Union general after another. One of the first big wins for the North was at The Battle of Antietam, in September 1862. The day it was fought remains the bloodiest day in American his- tory, with 23,000 casualties. Antietam turned a corner for the Union by stopping a northward advance by Lee’s army, and that victory gave Lincoln the confidence to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. On September 22, 1862, he made the sweeping, revolutionary announcement that all slaves in Confederate states would be free as of the following January 1.

Since the Proclamation applied only in states the federal government had no control over, it didn’t really free any- one except in a few Union-occupied parts of Confederate territory. But it told the world — and the captive blacks of the American South — that the war was not simply about preserving the Union. It was undeniably about slavery.

The war dragged on, with both sides more determined than ever after the Emancipation Proclamation. A turning point was reached in early July 1863, when Confeder- ate troops that had invaded the North were turned back in the epochal three-day battle in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, while in Mississippi, Union forces took control of the city of Vicksburg, freeing the Mississippi River from the Con- federacy. As President Lincoln put it, “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea.” That fall he delivered his great speech at the battlefield in Gettysburg, where 170,000 soldiers had clashed and 7,500 had been killed, saying “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

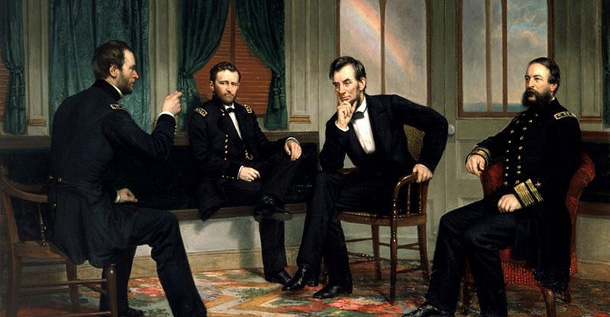

Many thousands more were yet to die, though. Lincoln finally found the commanding general he had been looking for in Ulysses S. Grant, and Grant pursued a relentless war of attrition against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, while General William T. Sherman cut a crippling swath through Georgia, devastating the heart of the deep South. The war dragged on until April 1865, when Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Just a week later, President Lincoln was assassinated by an enraged Confederate sympathizer, John Wilkes Booth.

The wounds left by the war did not quickly or easily heal. Reconstruction, a bitterly opposed attempt by the North to remake the South, lasted until 1877 and ultimately failed.

The Civil War brought an end to slavery and reunited the nation, but the pain of reconciling the differences, many of which began with the birth of the republic, lingers still. The war made our motto true E pluribus unum — from many, one — but the work of making us one is never complete.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now