“If you see a car along that road,” Tyler Nordgren warned me, “don’t look at the headlights. It’ll ruin your night vision for two hours.” Nordgren and I had pitched our tents under the brow of Mount Whitney in the Alabama Hills, a field of boulders near Death Valley. We watched it get dark, and in the nighttime horizon, the sky was perforated by stars and streaked by the Milky Way. Or, to put it in approximate scientific terms, it was probably a class 3 on the Bortle Dark-Sky Scale, the 9-level numeric metric of night sky brightness.

Even so, we could still see domes of hazy light from 200-odd miles south in Los Angeles and 250 miles east in Las Vegas. That encroaching urban glow was like highlighter calling attention to the issue that Nordgren, a prophet whose cause is light pollution, wanted to illustrate for me.

“We’re losing the stars,” the 45-year-old astronomer said. “Think about it this way: For 4.5 billion years, Earth has been a planet with a day and a night. Since the electric light bulb was invented, we’ve progressively lit up the night, and have gotten rid of it. Now 99 percent of the [continental U.S.] population lives under skies filled with light pollution.”

Nordgren is an affable, engaging, and quotable Cassandra, an enthusiastic and patient teacher who loves his subject and wants you to love it, too. Those attributes, along with his book for a lay audience, Stars Above, Earth Below: A Guide to Astronomy in the National Parks, have pushed him to center stage of a small but impassioned movement to preserve natural night skies. When he is not lecturing at the University of Redlands, a California liberal arts college, Nordgren is a much sought-after itinerant preacher intent on bringing people revelation of the stars they have, almost everywhere, lost sight of.

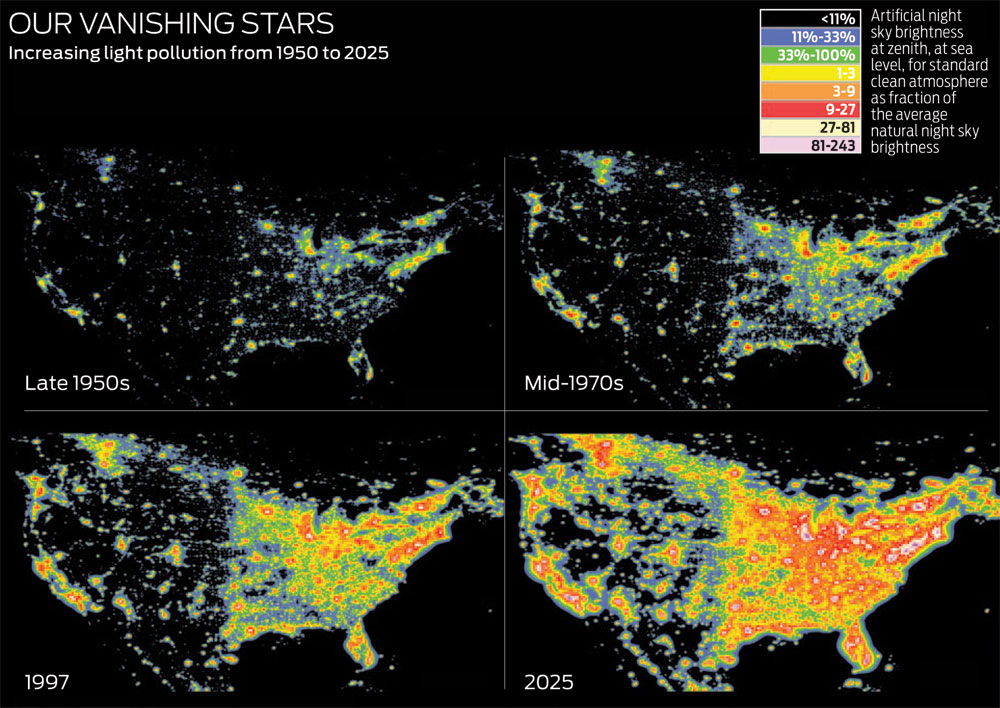

Our vanishing stars: Increasing light pollution from 1950 to 2025.

(P. Cinzano, F. Falchi [ISTIL-Light Pollution Science and Technology Institute],

C.D. Elvidge [NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder].

© Royal Astronomical Society. Reproduced from the Monthly Notices of the RAS by permission of Blackwell Science.)

Almost the entire eastern half of the United States, the West Coast, and almost every place with an airport large enough to receive commercial jets are too lit up to get a good view of stars. The phenomenon is illustrated by the first World Atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Based on spacecraft images of Earth in 1996-97, it shows a spectrum from black, representing the natural night sky, to pink, in which artificial light effectively erases any view of the stars at all. Green is where you lose visibility of the Milky Way. The map of the contiguous 48 states — and much of Europe — looks like a video-game screen showing a carpet bombing, the map a splash of green, yellow, red, and pink.

For roughly the past two decades, at least two-thirds of the U.S. population have not been able to see the Milky Way at all, and it will get worse before it gets better. …

To read the entire article from this and other issues, subscribe to The Saturday Evening Post.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now