In the November 21, 1914, issue: A German defends his country’s invasion of Belgium and a Canadian woman faces the scorn and pity of her neighbors after saving her husband from war.

Germany and England — the Real Issue

By Bernhard Dernburg

“England claims that she went to war on account of the breach of Belgian neutrality and that she must fight to destroy the spirit of militarism that has led to such a flagrant disregard of solemn treaties, a tendency that is endangering the peace of the world and consequently must be crushed entirely. … Unfortunately, in order to crush militarism … the German people will have to be destroyed as a nation. …

“It has been stated that militarism in general is a threat to the peace of the world. Yet German militarism has kept the peace for 44 years.”

Germany only built up this army because, centuries earlier, its peoples had been pushed around by other nations.

“[Germany’s] soil has been the rendezvous of Swedes, Danes, Russians, Croats, Poles, Italians, French, and Spaniards for centuries past. Impotent and not able to ward them off, she has been continually destroyed, until the genius of Bismarck welded her 26 states together into one unit, and Germany made the vow that she would never again give anyone such chances. That is why we kept our army, and if a people have an army at all, it is a waste not to make it strong enough for any emergency. That it is not too strong may be judged from the fact that Germany is now attacked by seven nations. …”

According to Dernburg, neutral Belgium only had itself to blame for the war that had swept across its land. Hadn’t Germany thoughtfully offered the Belgians an ultimatum, which they turned down?

“It should not be forgotten that the offer of indemnity to Belgium and the full maintenance of her sovereignty, had been made not only once but even a second time … and that it would have been entirely possible for Belgium to avoid all the devastation under which she is now suffering.”

Dernburg concluded by assuring Post readers that Germany had no intention of bothering the United States, or extending the conflict into the Western Hemisphere.

“I … would most emphatically say that, no matter what happens, the Monroe Doctrine will not be violated by Germany either in North America or in South America.”

Three years later, the German government offered Mexico a military alliance. If Mexican forces would help Germany defeat the United States, the German government would give the land of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona back to Mexico.

War and the Hearth

By Maude Radford Warren

A Canadian woman recalls the anxious days she knew before her husband left for the war. He was a veteran of the Boer War (1899-1902) and, once he returned to their Canadian farm, she explained to Warren why she hoped never to hear of war again.

“For a long time he didn’t let a word out of him, but sometimes his friends would talk round the dining-room table of nights when I had set out some cider and currant bread for them. I’d be sewing on the clothes of the baby that was coming, and I’d listen. And then I’d hear about … wounded men crying and calling for their mothers — and the night so black you couldn’t tell where they were, even if it would have done you any good to know. When you come to think of it, a grown-up man has to go through a lot of suffering before he begins to cry in the dark for his mother. I wish now I’d never heard any of those stories, for I can’t put them out of my mind.”

For weeks she had hoped her husband would remain with her, on the farm, if Great Britain entered the fight.

“Then I noticed how my husband would keep poring over the newspaper, and I got so I was afraid to look straight at him, for fear of what I might see in his face. Then I got so I didn’t say very much to him.

“One day at breakfast, when I was cutting bread for the children, he leaned across the table and took the knife and loaf away from me, and began to cut it himself. And when he’d got about twice as much as we could eat cut off — to get all dry and hard — he said: ‘Mary, you needn’t say anything to me. If war is declared I’m going!’

“Then he got up and left the table without drinking his tea. So I knew he felt bad at having to go against me — for I didn’t want him to go, at least not yet.”

As hard as it was to let her husband go off to war again, the woman said, it could be worse. A friend of theirs was now regretting her actions to keep her husband out of uniform.

“Sarah Jordan never seemed to me to set much store by her husband — they quarreled a good bit; but when this war broke out he enlisted. According to the law she had the right to hold him back, because he was a volunteer; so she wrote a letter to the colonel of the regiment and gave it to one of the children to post. Mr. Jordan got it away from the child. Then he told Sarah there was some loophole out of the law, and that they were going to take him anyway. She wouldn’t believe it entirely.

“Anyway, she was always one to do things before everybody, with a lot of fuss. So she went up to the armory one day when the men were drilling — not the company only, but the whole regiment, and flung her arms round Jordan’s neck and claimed him before everybody. They’re both the laughingstock of all their friends; but people feel sorry enough for him though, indeed, as my husband said, this is no time when a man wants to be pitied. But Mr. Jordan is putting in his time making Sarah wish she had let him go.”

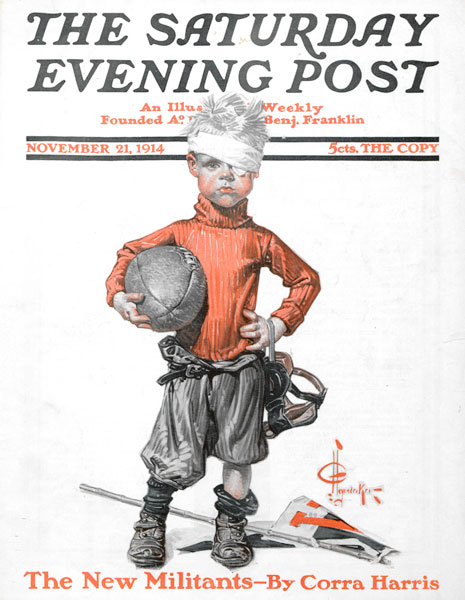

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now