The U.S. had a law against spying years before the Espionage Act was passed in 1917. In 1911, Congress passed the Defense Secrets Act after learning that spies in Europe escaped punishment because there were no laws against stealing secret documents.

The 1911 Act stated that anyone who entered a secured facility and removed information connected with national defense “shall be fined not more than one thousand dollars, or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.”

But that wasn’t considered strong enough once America entered World War I. President Woodrow Wilson wanted a law that imposed harsher penalties.

His Espionage Act of 1917, which now included the death penalty, made it a crime to obtain information related to national defense, record such information, communicate it, convey it to an unsecured location, or assist in any of these activities. It also outlawed delivering or attempting to deliver any information related to national defense to any foreign government.

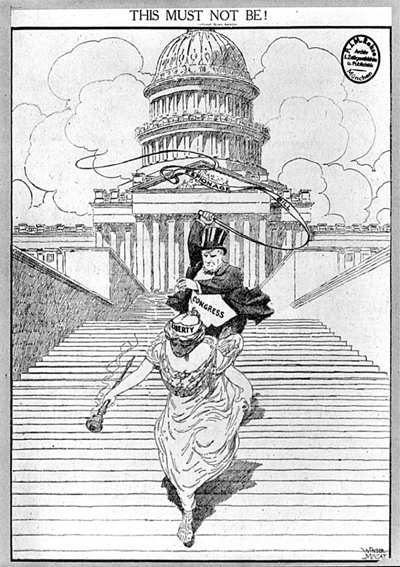

The Act was amended to include what was called The Sedition Act. It criminalized the use of “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” concerning the government, flag, or armed forces, or leading others to regard these things with contempt. It also empowered the Postmaster General to deny mail service to seditious publications.

The Act’s challenge to Free Speech was soon tested in court. Charles T. Schenck was arrested for mailing 15,000 antiwar leaflets to men who had recently been conscripted. The leaflets urged the draftees to oppose their conscriptions and petition the government to repeal the draft laws. Schenck was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, which upheld the verdict. Justice Oliver W. Holmes wrote that free speech could be curtailed when the nation was facing a “clear and present danger.”

Presidential candidate Eugene Debs spoke out against the war and was also convicted. He was sent to prison for 10 years.

In 1919 — a year after the war — socialist Victor Berger was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison for printing anti-war opinions. (“You got nothing out of the war except the flu and prohibition.”)

Meanwhile, Postmaster General Albert Burleson was exercising his power to restrict publications he deemed insufficiently patriotic. Around 60 publications had their mailing privileges terminated. Some were openly socialist, but some, like The Public: An International Journal of Fundamental Democracy, had its circulation stopped for simply repeating what President Wilson had already publicly said about funding the war.

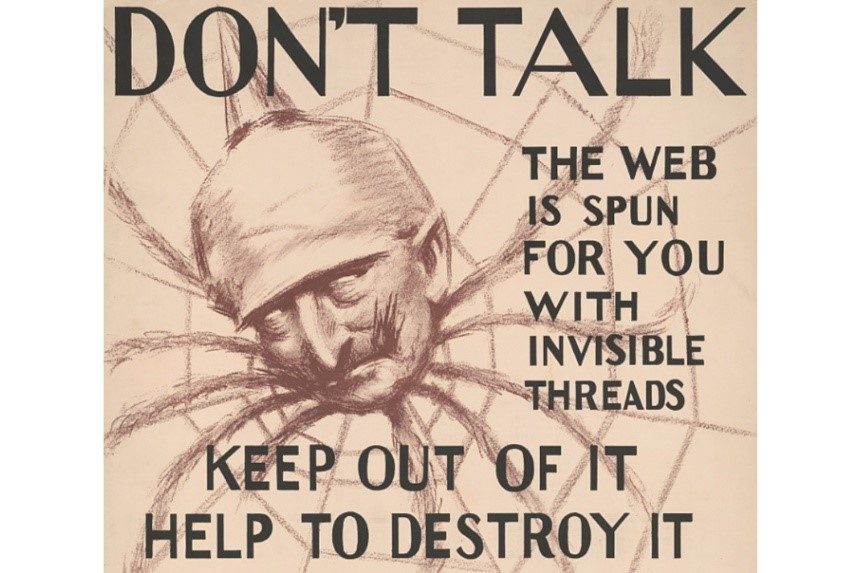

Wilson hadn’t wanted war, but he had convinced himself that this war could bring about final, global peace, according to The World Remade by G. J. Meyer. No effort could be spared to win such a great cause. The German government was now the enemy of civilization and, consequently, so were Americans who resisted or impeded Wilson’s efforts.

He believed immigrants had brought dangerous ideas into the country. In December of 1915, during his State of the Union address in which he asked Congress to pass the legislation, he argued:

There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws…who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt….Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out….I need not suggest the terms in which they may be dealt with.

Wilson was echoing the feelings of many xenophobic Americans who feared that immigrants — now comprising 13 percent of the population — were threatening the American way of life. They referred to the immigrants as hyphenated Americans, newcomers who claimed their new nationality without abandoning their traditional culture. The largest percentage were the eight million German-Americans, many of whom retained the ways of their ancestors. Even before the war, there had been pressure to shut down schools where only German was spoken. On June 15, 1918, the Post reported that Nebraska was taking action to eliminate all German teachers and German instruction. And the Senate Judiciary Committee had concluded German pressure on state legislatures had produced laws that helped the spread of “Germanism.”

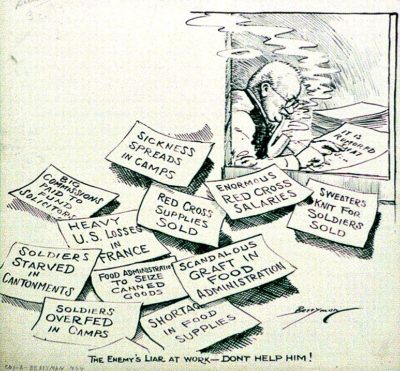

Today the most dangerous of our enemies are the half-secret ones of our own household. They come and go at will among us. Some spy out and report our military preparations; others foment strikes, set class against class, preach pacifism and pessimism and poison the springs of public thought. Thousands of these traitors take the Kaiser’s dirty dollar. Other thousands are merely half-baked perverts….

The menace from enemies at home is steadily increasing; the scope of their activities is steadily broadening. The Department of Justice can cope with those who commit certain overt acts, but it cannot lay by the heels the…disloyalists who are sheltered by the very Constitution of the nation they would destroy….

When you find a disloyal neighbor whom you can’t send to jail….shun him as if he had smallpox. Keep out of his house and keep him out of yours.

Some Americans wanted to do more than just shun enemies. They joined the American Protective League to become unofficial, unpaid informants for the Justice Department.

League members conducted raids or spied on suspected German sympathizers. They led spot checks of men’s draft registration cards. The League, which once claimed 250,000 members, turned in the names of neighbors they believed weren’t conserving food or gasoline.

One of the League’s biggest targets was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) whose aggressive activism on behalf of organized labor earned it many enemies. Empowered by the Espionage Act, the Justice Department, along with other law enforcement agencies, raided IWW offices and homes in 33 cities in September of 1917. They seized tons of papers, which were sent to Chicago and searched for evidence of collusion between the IWW and the German government. No evidence was found, but 166 senior IWW officers were indicted in Federal Court.

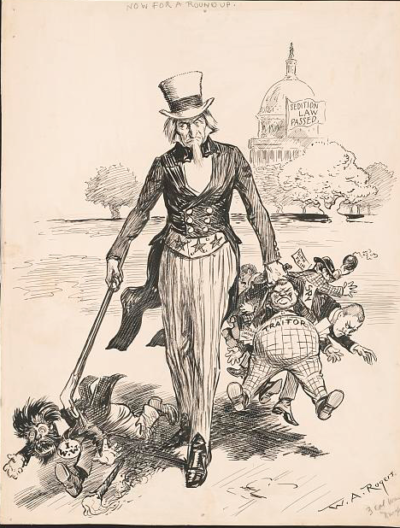

In 1919, attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer was prompted by a number of anarchist bombings to invoke the Sedition Act to roundup of perceived enemies in 30 cities. Over 3,000 people were arrested. Only the actions of a judge prevented an additional 650 New Yorkers being deported.

There were, of course, real foreign agents who had been active in pre-war America. Several German officials were expelled for spying, and a group of German saboteurs was arrested for blowing up a large ammunition depot in New Jersey. But these actions had all taken place before the Espionage Act was in place.

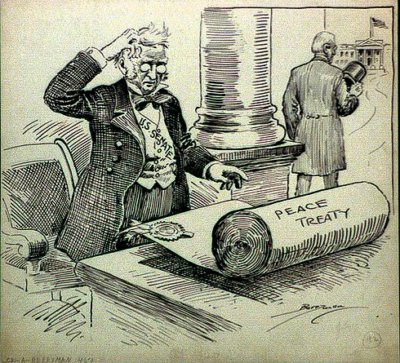

In August of the next year, after years of wrangling in Congress, the U.S. finally signed a peace treaty with Germany.

With the war officially concluded, Congress repealed many of the wartime laws. The Sedition Act amendment was repealed in December, but the Espionage Act was kept and remains in effect today.

A correction was made on September 1, 2022. International Workers of the World was changed to Industrial Workers of the World.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Quite often citizens’ vigilance does pay dividends, during WW2 in a quiet country lane in Kent, England, a lady was walking towards and past an approaching man, as they passed she murmured to him the words “Good Morning,” he never replied or nodded and hurried on his way, finding this strange she spotted a Policeman at the crossroads ahead and mentioned to him what had occurred, the Policeman agreed with her it was strange behaviour and hurried after the person she had pointed out to him, he was arrested, found to be a German spy who had landed earlier that day by parachute and who was later hanged. For what it’s worth I personally think all wars are futile and they never achieve their stated aims.

For how long will we remain the ‘land of the free and the home of the brave’ under Sharia Law? Under socialism, marxism, communism? Name another totalitarian -ism. When groups of foreigners band together before gaining a clear understanding of what our freedom really is and decide they must work toward a common goal of fixing a ‘broken and corrupted, racist system’, who will say there isn’t a threat to the nation? When they cross several borders to illegally enter our country with ill intent, how is that not a threat?

Since before WWI many different threats were recognized yet the responses to them were too passionate and poorly considered before enacting. With such hindsight, it shouldn’t be too difficult to rein in the horror and apply rational procedures and policies to prevent the troubles from the unknowing or ill-intended.

SO WHY WON’T OUR REPRESENTATIVES DO SO?

A correction is in order: It is NOT the INTERNATIONAL Workers of the World, but the INDUSTRIAL Workers of the World.

“Espionage Act” is a well-written perspective on our response to fearful situations. It echos current responses and gives a haunting reminder that there is a lot of work to be done if we truly want to be the “land of the free and the home of the brave.”