At least one in six Americans can remember the last time a U.S. president was assassinated. And almost all of them can tell you exactly where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news. They can probably also recall their feelings of sorrow, anger, and bewilderment when they heard President Kennedy was dead.

John Atherton

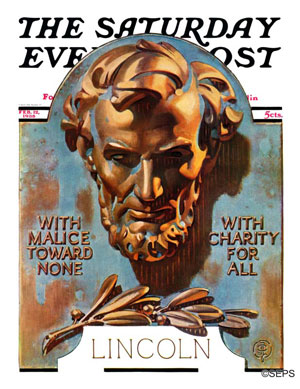

February 12, 1944

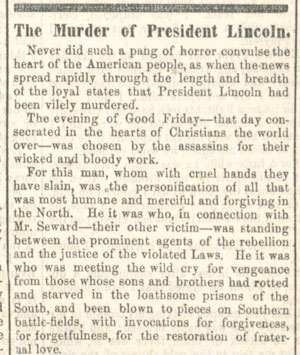

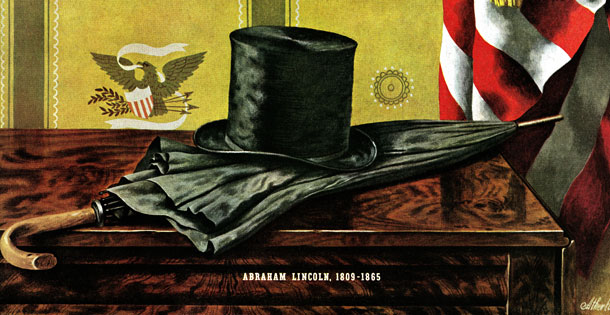

Those feelings must have been even more intense in Americans 150 years ago when they heard the news of the first presidential assassination. The president’s death would probably have seemed even more tragic as they realized that Lincoln would never see the reconciliation he’d worked so hard to achieve.

He’d spent the last four years holding the Union cause together, prodding generals, and supplying arms and men to defeat the Confederacy. But with victory in sight, he showed no animosity toward the Rebels. And though he had never spelled out his postwar plans for reconstructing the union, it was widely known he favored clemency toward the Southern secessionists.

Many in the North were hungry for vengeance, including Lincoln’s vice president, who advocated hanging many of the Southern “traitors.” Lincoln was one of the lone voices favoring forgiveness and reconciliation with the South. In his second inaugural address, he asked Americans “to bind up the nation’s wounds … to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace among ourselves.” Just a week before his death, while he was touring recently captured Richmond, a Union general asked Lincoln how he should treat the conquered Confederates. Lincoln said he didn’t want to give specific orders but added, “If I were in your place, I’d let ’em up easy, let ’em up easy.”

Days after the president’s death, Post editors wrote that they had once sided with the president’s “generous and merciful projects and desires.” But that was before he was shot by John Wilkes Booth, “a representative of those whom [Lincoln] was striving with all his might and influence to shield and benefit.”

The editors still admired Lincoln, but admitted he had a fault of leaning “too much towards gentleness and mercy.” Perhaps Lincoln was wrong, and God had intervened to correct the mistaken notion of mercy:

Has this cruel deed been allowed in the orderings of an all-wise Providence, that we may fully understand the hearts of these men with whom we have been contending, and waste no foolish magnanimity on those who seem incapable of responding to it? Such are the questions which at this moment every loyal man in the North is putting to himself.

To such questions, the editors had their answer: “We feel as if all other feelings were swept aside by the single demand for justice.” As for Lincoln’s call to forgive the South: “The voice of Mercy in our heart has been stilled forever” by the same bullet that silenced the voice of Lincoln.

History shows that vengeance grew stronger in the wake of Lincoln’s death, further complicating the reconciliation he had hoped to achieve.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

President Lincoln shot and killed,

Not just by one man, but by all

Whose rebel hearts and minds were filled

With disloyalty to appall.

“Loyal” news media so wrote,

Calling into question the will

Of the President to devote

A healing mercy to instill.

News media spread far and wide

Opinion that it was Divine –

Assassination to decide

Punish the South was the design.

Vengeance by news media spread.

The hopes of Lincoln had gone dead.