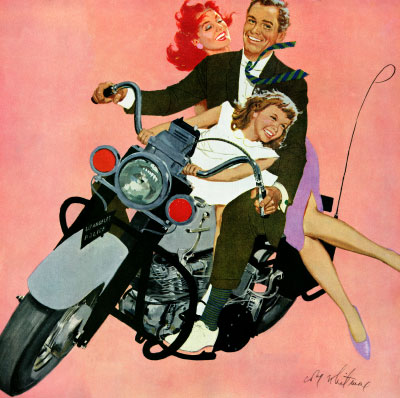

Illustrated by Coby Whitmore

The Saturday Evening Post, May 4, 1957

© SEPS

There was an olive tree at Peg and Willie Kidling’s cocktail party with a small girl in it. She was riding a high branch, like a horse. When she got out onto one of the smaller branches, her mother went over to the big tree.

“All right, Nicole. You’ve been up there long enough. Come on down now, and be very careful.”

“No,” the girl said. “I’m mad.”

I reached the party at half past six. I wanted to greet Peg anyway, so I went over to the tree, and she said, “How good to see you, Gunnar. Will you coax Nick out of the tree, please? I’m afraid she’s going to fall.”

Peg went off to greet some new arrivals, and I looked up. Nicole Kidling was looking straight at me.

“Who are you?”

“Gunnar Reykjavik.”

“What do you want?

“Your mother asked me to get you out of the tree.”

“Come and get me, then.”

I put my drink on the flagstone of the terrace and began to climb the tree.

“I know,” Nicole said. “You’re going to climb one or two branches and stop. You’re afraid to climb all the way up.”

“No, I’m not.”

“Yes, you are. You’re afraid you’ll fall.”

“No. This tree is perfectly safe. It’s very strong.”

“It’s over a hundred years old. My old mother told me. She’s over a hundred years old too. My old father’s over two hundred years old.”

I got up onto the second lowest branch and stood there.

Willie Kidling came over and began to laugh, and then half the people at the party came over too.

“Be careful, will you, Gunnar?”

“Hand me my drink, Willie.”

The ice-cold Scotch made me feel good, but I knew a lot of people were thinking, He must be crazy, whoever he is. I hadn’t kept up with Willie and Peg’s friends. I knew almost nobody at the party, certainly nobody in the crowd at the edge of the terrace. I handed the glass back to Willie.

“Take the people away, will you?”

Willie laughed again, and after a moment he took the people back to where the party was. I climbed up onto another branch and watched the party from there.

Everybody seemed happy except Peg. She kept trying to speak to her friends and at the same time to keep an eye on her daughter, a very plain little girl, nothing at all like her pretty mother. Peg was really worried about Nicole. I was a little worried myself, but I knew I’d have to go all the way up before she’d be willing to come down.

Peg came over quickly and said, “Be awfully careful, will you please, Gunnar? I didn’t expect you to climb the tree too.”

“I didn’t expect to either.”

“Della says if you don’t come down, she’s going to climb up.”

“Who’s Della?”

“Leonora Roma. But of course her real name is Della. It would be just too much if she started climbing the tree too.”

“Where is she?”

“All that tight purple over there.”

I saw Della, and, as luck would have it, she saw me and waved. Peg hurried back to Della—to stop her from coming to the tree, most likely.

“Is Della coming up too?” Nicole said.

“Do you know her?”

“Sure. Don’t you?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Don’t you know everybody?”

“Not by a long shot.”

“My mother does. She said so herself.

Is Della coming up too?”

Della came running over to the tree, with Peg chasing her.

Oh, no, Della, please! You can’t! You simply mustn’t!”

“But I want to.”

“No, please!” Peg took Della’s arm, while half a dozen men came along to watch and laugh as they sipped their drinks.

“I love climbing trees,” Della said.

“But you’ve seen this tree dozens of times and you’ve never before wanted to climb it.”

“But I never saw Nick in it before. And that other lunatic up there. Who’s he?”

“Gunnar Reykjavik,” Peg said. “Leonora Roma.”

“How do you do, Miss Roma.”

“Miss Roma my foot! My name is Della Harrigan. I’m from Arkansas, not Rome. And here I come.”

“Oh, no, please!” Peg said.

Della kicked off her high-heeled shoes. She grasped the lowest branch and planted her feet on the trunk of the tree. Then she swung up onto the lowest branch and stood there.

“How long have you been in America, Mr. Reykjavik?”

“I was born in San Francisco.”

“And you, Nick. How long have you?”

“All my life,” Nicole said.

“You coming up too?”

“I sure am.”

“No, you’re not.”

“Oh, yes, I am.”

“Why?”

“Because you’re up there,” Della said.

She glanced down at the men looking up, and then she said, “And because I can’t stand all those fat husbands down there. . . . Are you a husband, Mr. Reykjavik?”

“I was.”

“How long have you been divorced?”

“Two years.”

She swung up onto the second lowest branch. “What do you do?”

“Make a fool of myself, most of the time.”

“I know you do that. What work do you do?”

“If you climbed this tree to meet somebody important, Miss Roma —“

“Della Harrigan.”

“—you’ve made a mistake.”

“I don’t care if I have, Mr. Reykjavik. That’s that city in Greenland, isn’t it?”

“Iceland.”

“Yes. I knew it was one of those places. I can’t imagine why that silly publicity department at Universal gave me an Italian name. I’m an American, pure and simple.”

The small audience of husbands burst into loud laughter.

“Pure?” Della said. “Is that what you’re laughing at, you brutes? Well, I am pure, and I’ll thank you to go join your unhappy wives and let a girl from Little Rock try to meet a boy from San Francisco.”

She turned her handsome back to them quickly and almost slipped.

“You be very careful, Della,” Nicole said. “If you fall, I’ll really get the devil.”

“Don’t you worry about me, honey. I don’t fall—anywhere. Falling hurts my career . . . I’m a movie star, Mr. Reykjavik.”

“Everybody knows that,” Nicole said.

“He doesn’t.”

“Yes, I do.”

“Then why don’t you make a fuss over me, the way everybody else in America does? Fans, photographers, newspapermen, magazines, Prince Tournevire, Harry Hartington, and all those husbands down there on their way back to their wives at last. If you know I’m a movie star, why don’t you fall at my feet?”

“How can he, in a tree?” Nicole said.

“I don’t fall, either. Not any more, at any rate.”

“Were you terribly unhappy when you were married?”

“I was in love.”

“Oh, that’s the worst unhappiness of all.”

“I know, and never again.”

“Really?”

“Two years of marriage, two years of torching—that’s enough for me. Tree, terrace, town or country, I’m not falling any more.”

I swung up onto the second-highest branch and sat there, with Nicole a few feet away on a smaller branch.

“I never thought you’d climb all the way up.”

“Well, here I am, and let me have a look at you.”

“Why?”

“I like you.”

“You do not.”

“Yes, I do.”

“You’re just saying that. I’m not pretty. I know I’m not. And I don’t want to be, ever. My mother’s pretty. Her friends are pretty. Their little girls are pretty. Do you have a little girl?”

“No.”

“A little boy?”

“No.”

“How come?”

“Yes,” Della said. “You were married two years. How come?”

“It’s a long story.”

“Did you want a little girl?” the movie star said. She got up onto the next branch and stood there.

“I did.”

“All right. I’ve told you what I do, so now you tell me what you do.”

“Tell me, too,” Nicole said. “Are you a producer, like my father, or a director, or a writer, or an actor, or what?”

“Yes. Or what?” Della said.

“Hang on tight now—both of you.” They both hung on, and I told them: “I’m a cop.”

I’m a cop.”

“Oh, no!” Della said.

“Oh, yes!” Nicole said. “He is a cop. FBI.”

“No, motorcycle.”

“I don’t believe you,” Della said. “You don’t look like a cop and you don’t talk like one.”

“You can climb down now, Miss Roma. I told you I’m nobody.”

“I can climb up, too, but I’m going to stay right where I am for a minute. If you’re a cop, what are you doing at this party?”

“I came here from San Francisco twelve years ago to be best man at Willie’s wedding. I’ve been here ever since. Every once in a while, Peg and Willie invite me to one of their parties. I haven’t been to one in four or five years, but I thought I’d come to this one.”

“Why?”

“I hadn’t seen their kids in a long time and I thought I’d like to see them again. When they were little I used to know them quite well.”

“You did?” Nicole said. “Did you know me when I was little?”

“Yes, I did.”

“How come?”

“Well, your father was just getting started in those days, and whenever he wanted to take your mother to dinner with a lot of big movie people, he used to ask me to come over and baby-sit. I always said to myself, ‘This girl is a natural-born tree-climber.’”

“Bet your life I am,” Nicole said. “What does a motorcycle cop do—chase robbers?”

“Sometimes.”

“Money robbers?”

“Sometimes.”

“I think chasing robbers is the best work in the whole world. Not like being a silly old movie producer. Will you take me sometime?”

“Not when I’m chasing robbers, but I’ll take you for a ride sometime.”

“How about me?” Della said.

“Sure, if you want to go.”

“When?” Nicole said. “When will you take us? Both of us? Will you take us now? Right now?”

“I didn’t come to this party on a motorcycle.”

“Why not?” Della said.

“Nobody goes to a party on a motorcycle any more.”

“Well, how did you come?”

“I walked.”

“How far?”

“Oh, about six miles, I guess.”

“Can you go get your motorcycle and take us for a ride?” Nicole said.

“It’ll take me more than an hour to walk home and ride back.”

“No,” Della said. “I’ll drive you there, and we’ll all ride back together.” “

Will you, Della, really?” Nicole said.

“Of course, I will.”

“Well, what are we waiting for then?” Nicole said.

There were at least a hundred people at the party now. They were all so busy drinking and talking they didn’t notice us climbing down, except Peg, who began to move through the people on her way to the tree.

“Don’t let her punish me, will you, Della?” Nicole whispered.

“Your mamma’s not going to punish you,” Della said.

“That’s what you think. Wait and see.”

Peg was waiting for Nicole. She took her by the shoulders, looked at her a long time, and then said, “Oh, what’s the use? All right, Nick, join the party. A lot of people want to meet my daughter…. And thank you, Gunnar. How in the world did you get her down?”

“I came down to go for a ride on Gunnar’s motorcycle,” Nicole said.

“Me too,” Della said.

“What are you talking about?” Peg said. “Della, you’re the guest of honor. Everybody’s waiting to meet you.”

Della looked over at the people at the party. They weren’t waiting to meet anybody.

“Are you kidding?” she said. “Besides, there’s plenty of time.”

“Oh, no, Della. Please don’t go crazy on me just because my foolish daughter climbed that tree.”

“Crazy? Why, I’m having the best time I’ve ever had at a party.”

“Willie’s so proud you’re going to be in his new picture. He’s got dozens of important people he wants you to meet.”

“I’ve met them,” Della said. “I’ll meet them again too. Plenty of time.”

“We’ve got to go now,” Nicole said.

“This way, Della. I know a short cut around the pool. The other way you’ll run into all those people, and they’ll never let you go.”

“Nick, will you please shut up a minute?” Peg shouted. “I’ll be damned if you’re going to spoil every party your father gives! If you say another word, I swear I’m going to knock your head off!”

Nicole stood very straight, looking at her mother. Then she turned and fled, running around the pool, down the sloping lawn, to the fence, up the fence and over to the alley. As she ran she shouted, “I don’t want you! I don’t want your parties! I don’t want anything!” But of course nobody heard her and nobody saw her go, except the three of us standing under the tree.

“She’s a spoiled brat,” Peg said. Her lips trembled as she spoke.

When she tried to laugh, Della said, “Let’s go meet Willie’s friends, Peg.”

And that’s when I began to fall again. I wanted to go get Nicole, but I knew I had already gone a little too far, as usual. I like kids because they’re straight, and I like adults because it’s impossible for them to be straight and successful at the same time. I went over to where the drinks were being poured, got one, and waited for somebody I knew, so I could say something too. Anything. But nobody I knew showed up.

I went into the house, drinking on the way, but nobody I saw was anybody I knew, so I kept going until I got to the front door. I put the drink on the table there, went out and walked down the street to the alley. It was paved, with clean white board fences, most of them covered with ivy or honeysuckle. There was a mockingbird in a magnolia tree—Hollywood is full of them, bird and tree both—and the bird was mocking. Near the end of the alley where it comes to Benedict Canyon, I saw Nicole standing behind a mass of honeysuckle.

“Ask your mother to phone me sometime when it’s all right for you to go for a ride, and I’ll come and get you.”

I walked to Benedict Canyon, and then to Sunset, and before I knew it I was home, which is a two-room apartment over a garage on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood.

I hadn’t been upstairs three minutes when the doorbell rang. It was Nicole.

“How did you get here?”

“I followed you. Can I have a glass of water?”

I got her a glass of water. She drank it with the chopping sound of satisfaction only very thirsty kids have, so I got her another glass, and she drank that one too.

“Another?”

“No, thanks.” She looked around the apartment. “I had to see where you live. I guess I’d better get started back now. Good-by.”

“Good-by? You don’t think I’d let you walk back, do you?”

“I know my way.”

“I’ll take you back on my bike. And listen to me, will you, Nicole?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You and I behaved very badly this afternoon, and I’m very angry at myself.”

“I’m not angry at myself.”

“Well, all right, but when you get home, go to your mother and tell her you’re sorry. Everybody in a family has got to help everybody else.”

“O.K., but you don’t have to take me back. The party won’t end for hours. I know. They’re always supposed to be from five to seven, but they’re never over until long after I’ve gone to bed. Every time. I can walk back.”

“No; I promised you a ride, and this is my chance.”

“You don’t have to keep your promise.”

“Yes, I do.”

We went out onto the top of the stairway, and then down the wooden steps to the garage.

“Oh, golly!” she said when she saw the motorcycle. “Oh, what a beauty!”

I rolled the bike out of the garage to the driveway, placed her carefully on the front part of the seat, got on, and we were about to take off when a purple convertible with the top down rolled into the driveway with Della Harrigan at the wheel. She kept the convertible rolling slowly until it was alongside of us.

“I found Peg’s address book in the powder room. I want my ride.”

“Well, jump on, then. I’ve got to get you both back to the party.”

“It’s been a smashing success. I didn’t leave until I’d met everybody. They’ll all be there for hours.”

“Is Peg looking for Nicole?”

“Oh, no. The party’s going great. Nobody knows who’s still there or who’s gone. I’m sure everybody thinks I’m still there. We’ll all go back and have some more fun. What did you leave for?”

“I don’t know any of Peg’s and Willie’s friends these days.”

“I’m one of their friends. You know me.”

“Well, we’ve met.”

“Where do I sit?”

“Right behind me, and I’m afraid you’ll have to hang on real tight if you don’t want to find yourself sitting on the pavement.”

Della sat behind me and put her arms around me.

“A little tighter, I think.”

She tightened her grip, I started the bike, and we rolled down the driveway slowly to Franklin Avenue. Then we began to go. At the corner of Hollywood and Highland, there was Eddie Single- man on his bike, in uniform, on duty.

“Is that you, Gunnar?”

“Sure is, Eddie.”

“Sure is, Eddie.”

“Who are the pretty girls?”

“Tell him I’m your wife,” Della whispered.

“Mr. Singleman,” I said, “may I present my wife?”

“Pleased to meet you, Mrs. Reykjavik,” Eddie said.

“Likewise, I’m sure,” Della said.

“I’m their daughter,” Nicole said.

“Pleased to meet you, too, miss,” Eddie said.

“Miss Nicole Reykjavik,” Nicole said. “We’re all three of us part Icelanders. On my father’s side. On my mother’s we’re part Arkansas.”

“Taking the family out for a little Saturday-evening drive, Gunnar?”

“Yeah.”

“We could very easily buy a good secondhand car,” Della said, “but I always say don’t waste your money on luxuries, so you can afford another child. I’m quite pregnant right now.”

“Well, take care of yourself, Mrs. Reykjavik,” Eddie said…. “And, Gunnar, you drive careful now. Your wife’s pretty enough to be in pictures.”

“You’re very sweet to say that, Eddie,” Della said, “but I always say a woman’s place is in the home, taking care of her husband.”

“There ain’t many like you left,” Eddie said. “ Take it easy now.” He raced away.

“Oh, that was real nice,” Nicole said. “It was all lies, but it was fun just the same. Please don’t drive straight home.”

We rode down Highland to Sunset, and then up into the hills. When we were at the top of a hill we stopped to have a look at Hollywood away down there. Nicole took off to do a little exploring, and Della turned around, so I could have another look at her instead of Hollywood. I knew I’d better watch it, but I couldn’t. If a little girl is at the top of a tree and challenges me to get up there, I’ve got to get up there. If a big girl stands in front of me at the top of a hill in Hollywood and challenges me to take her in my arms, I’ve got to do it, movie star or no movie star.

“Again,” Della said.

“Don’t forget the little girl.”

“Well, kiss her too. She’s your daughter. And I’m your wife.”

“Don’t I wish you were, though?”

“Again.”

“No, enough’s enough, and here she comes, anyway.”

“Run to your mamma, please,” Della said.

Nicole ran with all her might into Della’s arms. Della hugged her, swept her off her feet, twirled her around twice and swung her out to me. I took the little girl and hugged her, and then Della hugged her while I was hugging her, and there we were. A family, almost.

We got back on the bike and started down the hill, winding around and around, the two women talking happily, and me trying to think, trying to figure out what to do about a thing like this because I was at their feet.

I stopped the bike two blocks from the Kidling house. “You’d better walk the rest of the way.”

They got off and Della kissed me the way a wife does when her husband’s going to work.

“You take good care of yourself now,” she said.

Then Nicole gave me a quick hug and they went off together.

I turned the bike around and drove to the station, in love again, tickled to death, and scared to death.

There was a five-handed game of stud in the back room, so I took a hand, got aces back to back, a third ace on the fifth card, against three kings, and took a big pot, almost three dollars, and this just isn’t my kind of luck at all. I generally lose.

At midnight I went on duty—Highway 101 Alternate from Santa Monica to the Ventura County line, straight through Malibu, Point Dume, Zuma Beach and Trancas.

The weekend traffic was still heavy and hectic. I could have stopped just about everybody and written out a ticket, but I didn’t because I had fallen again. All I did was ride along and hope nobody would crash or smash. I didn’t even stop a kid and his girl in a hotrod when he jumped a light.

I left the highway at Point Dume and rolled up and down the hills there. Nothing on the police radio was for me. And then, all of a sudden, it was. I looked at my watch—half past two—and took off as fast as I could go to Peg and Willie’s house.

“It’s all your fault!” Peg said. “You had no business climbing that tree. It’s three o’clock in the morning. Where’s my little girl?”

“Peg,” Willie said softly, “Gunnar’s my best friend.”

“I don’t care who he is,” Peg said. “My daughter’s been gone since half past six this evening, Mr. Reykjavik. Where is she?”

“Where’s Della?” I said.

“I don’t know and I don’t care. She had no business climbing the tree either. You people who don’t have kids are always making trouble for people who do.”

“Can you give me her address?”

Willie wrote the address on a card. I went out and got on my bike. I was on my way to Della’s when I thought I’d better go to my own place first. The purple car was still in the driveway.

I ran up the steps, went in, turned on the light, and there on the sofa was Della, fast asleep. She opened her eyes and sat up.

“What time is it?”

“Three, and what are you doing here?”

“1 had a little too much at the party, so when I came to get my car I thought I’d see if your door might be unlatched, and it was. I only expected to take a nap. I’m sorry if you’re annoyed. Are you?”

“Of course not. Not with you, at any rate.”

“You look annoyed. Who with, then?”

“Myself. Something’s happened, and it’s my fault.”

“Look, if you’re being blackmailed, I know a lawyer —“

“No, no. Listen, Della. Nicole’s disappeared. Now, please think back and think clearly. Tell me exactly what happened after Nicole and you got off the bike.”

“Why, we went back to the party, of course.”

“Did Nicole go to her mother?”

No. As a matter of fact, when we reached the front walk, she said she wanted to go around the back way. Under the circumstances, I agreed that that might be a good idea, so I went back to the party alone. Nobody noticed that I had been gone, even. I stayed quite a long time, too, and then Ricky Vale dropped me off here to pick up my car.”

“While you were at the party, did you see Nicole again?”

“No, come to think of it, I didn’t. I felt sure she was about, though. I can’t believe — What do you mean, she’s disappeared ?”

“I don’t get it, either, but there it is, and I’ve got to find her, that’s all.”

Della began to gather her things together. “What do you think’s happened to her?”

“I don’t know. Could be any number of things. As a cop, I know some of them could be pretty grim, but I’m not letting myself believe it might be any of them. I prefer to believe she’s hiding out somewhere.”

“Where?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I thought it might be at your house, if she happened to know where it is.”

“She knows. She’s been there many times.”

“And then I thought it might be here. It’s probably nearer home, though. A school friend maybe. She could even be hiding somewhere in the house itself.”

“Would Nicole do a thing like that?”

“I don’t know. She might.”

“What are the bad things?”

“I’d rather not talk about them.”

“Are they that bad?”

“They are. It happens all the time. Feeling hurt, she might just go along with anybody. She followed me all the way from her house to this house, to give you an idea. Are you all right? Can you drive?”

“Of course,” Della said. “I’ll be home in ten minutes. Why do you leave your door unlatched?”

“There’s no reason to lock it.”

“No wife? No kids? Is that what you mean?”

“I guess so.”

“Why don’t you marry me?”

“The girl I married asked me that question, so of course I married her. I don’t know how to take that question with a grain of salt.”

“Is this part of the long story you didn’t want to tell me in the tree?”

“It’s all of it. The rest is, she divorced me.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m nobody. The only kind of girl who might possibly be happy with a man like that would have to be a nobody, too—like the girl you pretended to be when I introduced you to Eddie Singleman—and I don’t think I’d be willing to impose a girl like that on my sons. After all, I owe them something too.”

“How about your daughters?”

“My family doesn’t have daughters. I’m the last of six sons. My brothers are all married and they’ve all got two or three sons each. We’ve always wanted daughters. We just haven’t got ‘em, that’s all. Good night.”

“Well, look,” Della said. “If you want to kiss me good night, you can, you know.”

“No. I’m still having a bad time from the last time I fell.”

“Be sure to phone. At any hour. I won’t be able to sleep.”

“O.K.”

I went out and rode back to Willie Kidling’s. The house had been searched from top to bottom. Also, the garage and the garden. The floodlights had been turned on all around the pool. The police and the press had come and gone, and come and gone again. I got back on the bike and rode off, but I just didn’t know which way to go. When a kid is lost, nobody can think and nothing helps. The only thing that can help is for the kid to be found, with no harm done. I drove to the station, but there was no news there, either. Everything was quiet everywhere. Why wouldn’t it be? It was four in the morning. I left the station and rode back to Beverly Hills. At daybreak it came to me, and it was silly, that’s all. It made sense, but it was silly too. I raced to the Kidling house, around to the alley, and stopped there. Nothing. Nobody. 1 climbed the fence and went up the sloping lawn, past the pool to the tree.

I climbed the tree again, but quickly this time. Nicole was wedged between two small branches at the top of the tree, half asleep. The foliage was so thick there, it wasn’t easy to see her. I took her hand and said her name very softly.

“Time to come down. But be very quiet and very careful, will you?”

“Where we going?”

“You’re going to your bed.”

“No. I won’t come down. My mother’ll kill me.”

“How long have you been up here, Nicole?”

“From the time you brought Della and me home. Nobody even saw me climb back up. I watched the whole party from up here. I fell asleep, and I didn’t wake up until all the lights were turned on again after the party.”

“You mean you saw them looking for you?”

“Of course I did.”

“Well, why didn’t you come down?”

“Why didn’t they come up? Why didn’t my mother? Why didn’t my father? I’m not coming down if you’re going to take me into that house.”

“Where do you want me to take you?”

“To your house. Or to.Della’s house.”

“Come on down, then.”

“Your house or Della’s?”

“Della’s.”

We got out of the tree and went down the sloping lawn to the fence, and over to the alley.

On our way to Della’s, Chuck Englehart drew up on his bike.

“Is that the lost girl, Gunnar?”

“This is my daughter, Chuck. She gets up early and I give her a ride every Sunday morning.”

“Are you sure, Gunnar? I’ve listened to the description all night. She answers the description.”

“Little girls have a lot in common.”

“If you’re sure, Gunnar, anything you say.”

Chuck rode off, and now I was scared because I knew Chuck didn’t believe me. I don’t know why, but I just couldn’t grab a little girl out of a tree, whack her bottom and take her, crying, into her house to her mother. I just couldn’t do that. I just had to believe a child has the same rights as an adult.

Both of the Sunday-morning papers were outside Della’s door, and a paper-delivery boy was at the other end of the hall. I could only hope he wouldn’t turn around, but he did.

I pressed the button and heard a chime, and Della came to the door. “We’ve got to speak very quietly.”

“Yes, of course,” Della said, “but where did you find her?”

“Let Nicole tell you. I’ll fix her some breakfast.”

Della and Nicole went down a long hall to her bedroom, and I went to the kitchen. Orange juice. Boiled eggs. Bacon. Toast. I put the stuff on a tray and took it to Della’s bedroom.

Della brought Nicole out of the bath, wrapped in a heavy purple towel.

“There’s a hot breakfast for you, Nicole. Please eat it and get a little sleep—in a bed this time.”

“I’m wide awake,” Nicole said.

“Well, eat your breakfast and just rest in bed then.”

I went back to the kitchen, and after a few minutes Della came there too.

“Is she all right?”

“I think she’s a little scared.”

“Well, I’ve done it again.”

“You found her, didn’t you?”

“Yes, but I should have taken her straight to her mother and father.”

“Well, why in the world didn’t you?”

“She didn’t want me to.”

“You are a nut, aren’t you?”

“Yes, I’m afraid I am. Now, look,there’s a way of straightening this whole thing out without hurting anybody— Nicole, Peg, Willie, you, the police, the press, the people.”

“What people?”

“The people who like to read about the troubles of other people.”

“Oh, them,” Della said. “Well, this is none of their business.”

“It is now. Nicole Kidling, daughter of the famous producer, William Kidling, and the famous actress, Peggy Barker…. How do you like your eggs?”

“Scrambled, medium.” Della fetched the morning papers and spread them out on the kitchen table.

“Oh, no!” she said. “Two pictures of Nicole on the front page, one each of Peg and Willie, and the names of just about everybody who was at the party. Well, if Peg wanted a successful party, she certainly got it. And she can thank her daughter too. She’s always felt her parties haven’t gotten enough attention, not even from Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper. This party’s on the wire services. If I didn’t know the truth, I’d say it was a publicity stunt. Listen to this: ‘The guest of honor at the party was the madcap Leonora Roma, who is to star in Mr. Kidling’s next picture, High as a Kite.’ I don’t understand where they get that madcap stuff. For six long years all I’ve done is work very hard.”

I put the plate of scrambled eggs and bacon in front of Della.

“What’s the matter with you? Aren’t you eating?”

“No, I can’t. Please try to help me, Miss Roma. What do we do? Do we call Willie and tell him, or what?”

“I don’t know why not. I’ll tell him plenty too. I’ve got half a mind to go on suspension. He’s got his nerve plugging his picture at my expense. And Nicole’s too.”

“Yes, we’d better not forget Nicole. Before you phone, we’d better talk to her.”

“What about?”

“The three of us have got to agree on a story that won’t hurt anybody.”

“Well, what’s the matter with the truth?”

“No, that won’t do at all.”

“Why not?”

“Well, for one thing, she was right there the whole time, and that’ll make the mother and the father look silly, and the police too. The truth’ll make it look even more like a publicity stunt than it already does too.”

“I do sympathize with Peg, though.”

“Of course. you do.”

“Oh, I don’t mean about Nicole. I mean about her career. It just came to a stop five or six years ago, and she just won’t quit. She gets one or two small parts a year and tries to believe she’s still a star. A party a month, she averages. A big party, I mean. Two or three little ones every week. Who’s important now? Who’s new? Get them over to the house, and maybe something’ll happen to her career. How can you expect the little girl not to be lost in an atmosphere like that? Peg just hasn’t got any time for Nicole.”

“Try not to be too critical of a mother until you’re one yourself.”

“Well, it’s the truth.”

“Only kids are entitled to live by the truth. The rest of us have got to live by lies.”

“You don’t.”

“I do my best.”

“By pretending to be a cop? You’re no cop.”

“I am, and I’m not pretending. Could you say you came home after the party and went to bed? Early in the morning Nicole walked into your bedroom and confessed that she had spent the night? Is there a place somewhere in the apartment where she might have slept?”

“Well, there’s a second bedroom— very small. I almost never look in there. The maid just keeps it clean and shuts the door.”

“Would that be all right with you?”

“Sure, if you think it’ll be all right with everybody else.”

“You’re very kind, Miss Roma.”

“Oh, now, look here. I asked you long ago to please lay off that Miss Roma stuff. I’m not an actress in my own home.”

“O.K. We haven’t got too much time. The sooner we let Peg and Willie know, the better. Do you think Nicole’s rested enough now to go over the story with us?”

“What for?”

“It might be too late later, but even if it weren’t, Nicole has got to agree to the story.”

“That’s silly. She’s just a little girl.”

“She isn’t going to be little forever. Will you see if she’s awake?”

“What’s the rush?” “The police are going to pay you a visit very soon. And when they do, I’d better not be here.”

“Why not?”

“I’m a cop, I’m not off duty until eight o’clock in the morning, and what am I doing here?”

“Visiting me—a friend.”

“Oh, just fine. That’ll be just fine, won’t it?”

“Well, won’t it?”

“A cop in uniform here with just about the most beautiful girl in the world?”

“More beautiful than the girl who divorced you?”

“Well, maybe not more beautiful, but certainly not less.”

“Are you in love with me?”

“Suppose I were?”

“I’d ask you to buy me a little house

with an adjoining olive tree.”

“What for?”

“So when we have a daughter, she can climb it, and we can climb up after her.”

“Nicole’s the only daughter you and I will ever have. The only one we’ll ever climb a tree about too. We’ve had her, and now we’ve got to get her back to her mother and father.”

“They won’t climb a tree about her.”

“They won’t have to because she won’t want them to, any more, after we agree on a story.”

“Are you in love with our daughter too?”

“Nicole? Of course I am. She’s the first daughter in six generations of the Reykjavik family.”

“No, not Nicole; our own.”

“I’ve already told you I can’t take talk like this with a grain of salt.”

“I believe you really do love me.”

“Yes, I believe I do.”

“And I believe you believe I don’t mean a word I’m saying.”

“Yes, I believe that too.”

“Well, marriage isn’t everything, and I’ve been married twice, as you know.”

“Yes, it’s like money all right. It isn’t everything.”

“It turns a good man into a husband overnight, and I just can’t stand them— mine or anybody else’s.”

“Well, in a way we’ve been married anyhow, we’ve had an eight-year-old daughter in a tree, and maybe that’s as good as we’d ever be likely to do, in any case.”

Della got up and came around the table. “Well,” she said, “let’s kiss our little marriage good-by, then, and go about our business, shall we?”

“Yes, I think that that’s the grown-up thing to do.”

I held her head in my hands a moment, and then I put one on her forehead just above her watching left eye. I felt proud of myself for watching it so well.

“Cold,” Della said. “Courteous and cold, as a good-by kiss should be from a man from Iceland.”

“Well, that takes care of the marriage.”

“Now,” Della said, “one to take care of our daughter—on the mouth.”

Well, she was there, with her mouth open in a little smile, so what could I do? I put one there, too, only I didn’t watch it very well, and there went four arms around two people all of a sudden—one of them Della Harrigan and the other myself, whoever I am, so far from Iceland, so many years later. I kept trying to watch it, but I just couldn’t. There just wasn’t anything else to do but let Iceland melt and go, and hold on to Della forever. I just might have done it, too, if I hadn’t heard a lot of car doors slamming, and there down in the street I saw the police and press getting out of cars and running into the building.

“Well, here they come, and we haven’t got Nicole’s approval of the story. Better use it just the same. I’ll go out the back.”

“There is no back,” Della said.

The door chime sounded, and then somebody knocked softly.

“You open it,” Della said.

I went to the door, trying to clear my head on the way. I opened the door and they came in—my boss Captain Salvi, Chuck Englehart, two other cops, the paper-delivery boy, three men with flash cameras, and three others—reporters, most likely.

“Can we please try to be quiet, Captain Salvi? The little girl’s asleep.”

Captain Salvi went to work asking me questions, and I tried my best to answer them without hurting anybody, especially Nicole and Della.

Captain Salvi said, “Reykjavik, if what you say is true, and the girl spent the nigh there,I’d like the press to see her. This case has created a great deal of public interest, and we owe it to the people to let them know the child is all right.”

Della looked at me. “If you’ll come with me, please,” she said, “you may bring her out.”

“Have I your permission, Captain Salvi?”

“Please do as Miss Roma says.”

Della led the way down the long hall to her bedroom. She opened the door and we went in. Nicole was not in Della’s bed. Della closed the door behind her quickly, bolted it, and I went to the night table and picked up a piece of letter paper on which a message had been printed in pencil.

I handed Della the message: “I herd what you said. Your just like all the others. Good by. Nicole K.” “Well, what in the world did we say?” “Who knows? Well, we’ve got to go back and tell ‘em the truth, that’s all. From the beginning to the end. Otherwise we’ll never get out of this. Come on.”

“But what about Nicole? Where is she now?”

“She’s probably back in the tree. Come on; the longer we stay in here the worse it is for you.”

“I can’t be bothered about that.”

Della began to dial the telephone on the night table. “Willie?” she said suddenly into the phone. “This is very important. Don’t ask any questions. Just do what I tell you. Run out into the garden to the olive tree and look up, and then run right back, will you? I’ll be waiting.” She put down the phone. “What do you think?”

“Well, I can only hope she is back in the tree, because then this whole thing will be worked out the way it ought to be—except, of course, for you. I mean, on account of me. What’s the press going to think about that?”

“I don’t know and I don’t care,” Della said. “Do you?”

“I certainly don’t want to involve you in a silly scandal.”

“So it turns out the whole world believes you’re a boy friend, as the saying is. So what?”

“If it’s O.K. with you, it’s O.K. with me. Boy friend it is, then.”

“If the worst came to the worst, we could even get married.”

“You don’t want to get married.”

“Of course I don’t, but we could just the same, couldn’t we?”

“I couldn’t marry somebody who didn’t want to get married. I’m no gigolo, or whatever they are.”

“Well,” Della said, “if the little girl’s safe at home, maybe I’ll want to get married.” She began talking into the phone again suddenly, “Willie? Yes, I’m here.” She listened a moment, and then she said, “Now, listen, will you? Go and wake up Peg, and both of you climb the tree, and meet your daughter. I think you’ll like her. Yes, you’ve got to do that! Both of you. But make it fast because half the world is going to be there in a few minutes.”

Della listened a moment, and then she said, “Of course he’s here. We’re going to be married.” She listened a moment again, and then she said, “What do you mean, I should think twice about a thing like that? I’ve already thought twice. If Grace Kelly can marry the Prince of Monaco, and Rita Hayworth can marry Aly Khan of India, why can’t Della Harrigan marry a man from Iceland? What do I care what it’ll do to the box office? Well, now, look, Willie, if you’re finished being worried about Nicole because she’s home again, and now you’re worried about High as a Kite, maybe you’d better get another girl, because I’m really a little tired of working, anyway. I might just like to go on a voyage to Iceland and have a look at the place, and if I like it, I might just want to stay too. I’m glad Nicole is safe in the tree again. Good-by.

She hung up.

“Would you like to take me on a voyage to Iceland?”

“I’ve never been there, but I certainly would. In the meantime, I believe there’s some people outside the door, listening.”

“Well, suppose we talk a little louder, then?”

“I’m game.”

“Well, then, ask me to be your wife,” Della whispered.

“Della,” I said in a loud clear voice, “will you be my wife?”

“Yes, I will, Gunnar. Will you take me to Iceland?”

“Yes, I will.”

“In that case,” Della said, “swing the door open and let’s embrace for the police and the press, and then you can carry me across the threshold of my boudoir. After that, I want to go to sleep, while you go and turn in your bike, your badge and your cap.”

I went to the door, unbolted it opened it, and there stood Captain Salvi, Chuck Englehart, three cameramen, three reporters, the paper-delivery boy and six or seven people I’d never seen before.

“Nicole Kidling is safe at home. Della Harrigan has consented to be my wife, and as soon as we’re married, I’m taking her on a voyage to Iceland, the land of my ancestors.”

I went to Della, who was standing at the window with her lovely back turned to police, press, publicity, pictures and people in general.

“Della?”

She turned around. “There’s always a first time, you know,” she said.

“Which first time are you thinking of?”

“That your family has a daughter.”

“Yes, it could happen.”

“Let’s kiss to that, then.”

I didn’t need to watch it any more, so I really kissed her this time. A lot of voices made strange human sounds, camera lights flashed, olive trees sprang up all over the place, with a little girl in every one of them, and I just couldn’t be bothered any more about Captain Salvi, police rules and regulations, or law and order.

I just couldn’t be bothered any more about anybody except Della Harrigan and the daughter we both hoped to find in a tree someday.

Read more classic fiction by famous contributors:

Stephen Vincent Benet

Dorothy Parker

Kurt Vonnegut

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Oops! Incomplete second sentence: ‘The fact it took place in the Hollywood Hills area mentioning real streets like Franklin and Benedict Canyon, made it fun to visualize.’

For all of the comments I make, this goof is a first. It’s a little embarrassing, so what can I say? Happy Presidents Day to EVERYONE at the POST!

This is the first online POST story I’ve had to read in three sections, and it was enjoyable. The fact it took place in the Hollywood Hills area mentioning real streets like Franklin and Benedict Canyon.

One of the ironies of the story was that the little girl felt she was ugly, yet she’s one of the beautiful people on that motorcycle illustration by Coby Whitmore, one of my favorite illustrators along with Jon Whitcomb. Let’s be honest here, neither of these guys ever painted anyone or anything that didn’t look perfect.

This POST issue is just a few weeks older than me, and I can picture the ‘wow’ factor it had then being on those over-sized pages. Truthfully it could almost pass as being from the present, with the only thing looking vintage is the motorcycle. I’m glad it’s available at art.com to buy!