Dr. Joseph Cyr, a surgeon lieutenant of the Royal Canadian Navy, walked onto the deck of the HMCS Cayuga. It was September 1951, the second year of the Korean War, and the Cayuga was making her way north of the 38th parallel, just off the shore of North Korea. The morning had gone smoothly enough; no sickness, no injuries to report. But just as the afternoon was getting on, the lookouts spotted something that didn’t quite fit with the watery landscape: a small, cramped Korean junk that was waving a flag and frantically making its way toward the ship.

Within the hour, the rickety boat had pulled up alongside the Cayuga. Inside was a mess of bodies, 19 in all, piled together in obvious filth. They looked close to death. Mangled torsos, bloody, bleeding heads, limbs that turned the wrong way or failed to turn at all. Most of them were no more than boys. They had been caught in an ambush, a Korean liaison officer soon explained to the Cayuga’s crew; the messy bullet and shrapnel wounds were the result. That’s why Dr. Cyr had been summoned from below deck: He was the only man with any medical qualification on board. He would have to operate — and soon. Without his intervention, all 19 men would very likely die. Dr. Cyr began to prepare his kit.

There was only one problem. Dr. Cyr didn’t hold a medical degree, let alone the proper qualifications required to undertake complex surgery aboard a moving ship. In fact, he’d never even graduated high school. And his real name wasn’t Cyr. It was Ferdinand Waldo Demara, or, as he would eventually become known, the Great Impostor — one of the most successful confidence artists of all time, memorialized, in part, in Robert Crichton’s 1959 account The Great Impostor. His career would span decades, his disguises the full gamut of professional life. But nowhere was he more at home than in the guise of the master of human life, the doctor.

Over the next 48 hours, Demara would somehow fake his way through the surgeries, with the help of a medical textbook, a field guide he had persuaded a fellow physician back in Ontario to create “for the troops” in the event a doctor wasn’t readily available, copious antibiotics (for the patients) and alcohol (for himself), and a healthy dose of supreme confidence in his own abilities. After all, he’d been a doctor before. Not to mention a psychologist. And a professor. And a monk (many monks, in fact). And the founder of a religious college. Why couldn’t he be a surgeon?

As Demara performed his medical miracles on the high seas, makeshift operating table tied down to protect the patients from the roll of the waves, a zealous young press officer wandered the decks in search of a story. The home office was getting on his back. They needed good copy. He needed good copy. Little of note had been happening for weeks. He was, he joked to his shipmates, practically starving for news. When word of the Korean rescue spread among the crew, it was all he could do to hide his excitement. Dr. Cyr’s story was fantastic. It was, indeed, perfect. Cyr hadn’t been required to help the enemy, but his honorable nature had compelled him to do so. And with what results. Nineteen surgeries. And 19 men departing the Cayuga in far better shape than they’d arrived. Would the good doctor agree to a profile, to commemorate the momentous events of the week?

Who was Demara to resist? He had grown so sure of his invulnerability, so confident in the borrowed skin of Joseph Cyr, M.D., that no amount of media attention was too much. And he had performed some pretty masterful operations, if he might say so himself. Dispatches about the great feats of Dr. Cyr soon spread throughout Canada.

Dr. Joseph Cyr, original version, felt his patience running out. It was October 23, and there he was, sitting quietly in Edmundston [New Brunswick], trying his damnedest to read a book in peace. But they simply wouldn’t leave him alone. The phone was going crazy, ringing the second he replaced the receiver. Was he the doctor in Korea? the well-intentioned callers wanted to know. Was it his son? Or another relative? No, no, he told anyone who bothered to listen. No relation. There were many Cyrs out there, and many Joseph Cyrs. It was not he.

A few hours later, Cyr received another call, this time from a good friend who now read aloud the “miracle doctor’s” credentials. There may be many Joseph Cyrs, but this particular one boasted a background identical to his own. At some point, coincidence just didn’t cut it. Cyr asked his friend for a photograph.

Surely there was some mistake. He knew precisely who this was. “Wait, this is my friend, Brother John Payne of the Brothers of Christian Instruction,” he said, the surprise evident in his voice. Brother Payne had been a novice when Cyr knew him. He’d taken the name after shedding his secular life — and that life, Cyr well recalled, was a medical one much like his own. Dr. Cecil B. Hamann, he believed the man’s original name was. But why, even if he had returned once more to medicine, would he ever use Cyr’s name instead? Surely his own medical credentials were enough. Demara’s deception rapidly began to unravel.

And unravel it did. But his eventual dismissal from the navy was far from signaling the end of his career. Profoundly embarrassed — the future of the nation’s defense was on its shoulders, and it couldn’t even manage the security of its own personnel? — the navy did not press charges. Demara-alias-Cyr was quietly dismissed and asked to leave the country. He was only too happy to oblige, and despite his newfound, and short-lived, notoriety, he would go on to successfully impersonate an entire panoply of humanity, from prison warden to instructor at a school for “mentally retarded” children to humble English teacher to civil engineer who was almost awarded a contract to build a large bridge in Mexico. By the time he died, over 30 years later, Dr. Cyr would be but one of the dozens of aliases that peppered Demara’s history. Among them: that of his own biographer, Robert Crichton, an alias he assumed soon after the book’s publication, and long before the end of his career as an impostor.

Time and time again, Demara — Fred to those who knew him undisguised — found himself in positions of the highest authority, in charge of human minds in the classroom, bodies in the prison system, lives on the decks of the Cayuga. Time and time again, he would be exposed, only to go back and succeed, yet again, at inveigling those around him.

How was he so effective? Was it that he preyed on particularly soft, credulous targets? I’m not sure the Texas prison system, one of the toughest in the United States, could be described as such. Was it that he presented an especially compelling, trustworthy figure? Not likely, at 6-foot-1 and over 250 pounds, square linebacker’s jaw framed by small eyes that seemed to sit on the border between amusement and chicanery, an expression that made Crichton’s 4-year-old daughter Sarah cry and shrink in fear the first time she ever saw it. Or was it something else, something deeper and more fundamental — something that says more about ourselves and how we see the world?

Hard crime — outright theft or burglary, violence, threats — is not what the confidence artist is about. The confidence game — the con — is an exercise in soft skills. Trust, sympathy, persuasion. The true con artist doesn’t force us to do anything; he makes us complicit in our own undoing. He doesn’t steal. We give. He doesn’t have to threaten us. We supply the story ourselves. We believe because we want to, not because anyone made us. And so we offer up whatever they want — money, reputation, trust, fame, legitimacy, support — and we don’t realize what is happening until it is too late. Our need to believe, to embrace things that explain our world, is as pervasive as it is strong. Given the right cues, we’re willing to go along with just about anything and put our confidence in just about anyone. Conspiracy theories, supernatural phenomena, psychics: We have a seemingly bottomless capacity for credulity. Or, as one psychologist put it, “Gullibility may be deeply ingrained in the human behavioral repertoire.” For our minds are built for stories. We crave them, and, when there aren’t ready ones available, we create them. Stories about our origins. Our purpose. The reasons the world is the way it is. Human beings don’t like to exist in a state of uncertainty or ambiguity. When something doesn’t make sense, we want to supply the missing link.

Courtesy CP Photo

When we don’t understand what or why or how something happened, we want to find the explanation. A confidence artist is only too happy to comply — and the well-crafted narrative is his absolute forte.

The confidence game has existed long before the term itself was first used, likely in 1849, during the trial of William Thompson. The elegant Thompson, according to the New York Herald, would approach passersby on the streets of Manhattan, start up a conversation, and then come forward with a unique request. “Have you confidence in me to trust me with your watch until tomorrow?” Faced with such a quixotic question, and one that hinged directly on respectability, many a stranger proceeded to part with his timepiece. And so, the “confidence man” was born: the person who uses others’ trust in him for his own private purposes. Have you confidence in me? What will you give me to prove it?

The con is the oldest game there is. But it’s also one that is remarkably well-suited to the modern age. If anything, the whirlwind advance of technology heralds a new golden age of the grift. The same schemes that were playing out in the big stores of the Wild West are now being run via your inbox; the same demands that were being made over the wire are hitting your cellphone. A text from a family member. A frantic call from the hospital. A Facebook message from a cousin who seems to have been stranded in a foreign country. When Catch Me If You Can hero Frank Abagnale, who, as a teen, conned his way through most any organization you can imagine, from airlines to hospitals, was recently asked if his escapades could happen in the modern world — a world of technology and seemingly ever-growing sophistication — he laughed. Far, far simpler now, he said. “What I did 50 years ago as a teenage boy is 4,000 times easier to do today because of technology. Technology breeds crime. It always has, and always will.”

Since 2008, consumer fraud in the United States has gone up by more than 60 percent. Online scams have more than doubled. Back in 2007, they made up one-fifth of all fraud cases; in 2011, they were 40 percent. In 2012 alone, the Internet Crime Complaint Center reported almost 3,000 complaints of online fraud. The total money lost: $525 million.

For the total U.S. population, between 2011 and 2012 — the last period surveyed by the Federal Trade Commission — a little over 10 percent of adults, or 25.6 million, had fallen victim to fraud. The total number of fraudulent incidents was even higher, topping 37.8 million. The majority of the cases, affecting just over 5 million adults, involved one scheme: fake weight-loss products. In second place, at 2.4 million adults: prize promotions. Coming in third, at 1.9 million: buyers’ clubs (those annoying offers you usually toss out with the recycling, where what seems like a free deal suddenly translates to endless unwanted, and far from free, charges for memberships you didn’t even know you signed up for), followed by unauthorized internet billing (1.9 million) and work-at-home programs (1.8 million). About a third of the incidents were initiated online. Last year in the U.K., an estimated 58 percent of households received fraudulent calls, seemingly from banks, police, computer companies, or other credible-sounding businesses. Some call recipients were wise to the scam. But somehow, close to £24 million was lost to the scammers — up from £7 million the year prior.

Countless more cases go unreported — most cases, in fact, by some estimates. According to a recent study from the AARP, only 37 percent of victims older than 55 will admit to having fallen for a con; just over half of those under 55 do so. No one wants to admit to having been duped. Most con artists don’t ever come to trial: They simply aren’t brought to the authorities to begin with.

No matter the medium or the guise, cons, at their core, are united by the same basic principles — principles that rest on the manipulation of belief. Cons go unreported — indeed, undetected — because none of us want to admit that our basic beliefs could be wrong. It matters little if we’re dealing with a Ponzi scheme or falsified data, fake quotes or misleading information, fraudulent art or doubtful health claims, a false version of history or a less-than-honest version of the future. At a fundamental, psychological level, it’s all about confidence — or, rather, the taking advantage of somebody else’s.

The confidence game starts with basic human psychology. From the artist’s perspective, it’s a question of identifying the victim (the put-up): Who is he, what does he want, and how can I play on that desire to achieve what I want? It requires the creation of empathy and rapport (the play): An emotional foundation must be laid before any scheme is proposed, any game set in motion.

Only then does it move to logic and persuasion (the rope): the scheme (the tale), the evidence and the way it will work to your benefit (the convincer), the show of actual profits. And like a fly caught in a spider’s web, the more we struggle, the less able to extricate ourselves we become (the breakdown). By the time things begin to look dicey, we tend to be so invested, emotionally and often physically, that we do most of the persuasion ourselves. We may even choose to up our involvement ourselves, even as things turn south (the send), so that by the time we’re completely fleeced (the touch), we don’t quite know what hit us. The con artist may not even need to convince us to stay quiet (the blow-off and fix); we are more likely than not to do so ourselves. We are, after all, the best deceivers of our own minds. At each step of the game, con artists draw from a seemingly endless toolbox of ways to manipulate our belief. And as we become more committed, with every step we give them more psychological material to work with.

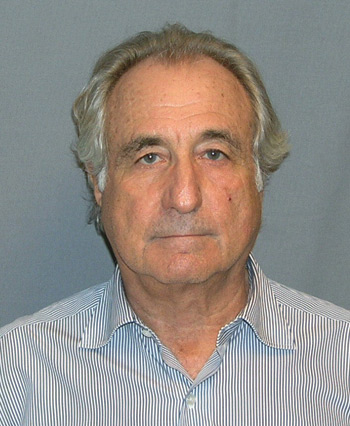

U.S. Department of Justice

Everyone has heard the saying “If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.” Or its close relative, “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” But when it comes to our own selves, we tend to latch on to that “probably.” If it seems too good to be true, it is — unless it’s happening to me. We deserve our good fortune. I deserve the big art break; I’ve worked in galleries all my life and I had this coming. I deserve true love; I’ve been in bad relationships long enough. I deserve good returns on my money, at long last; I’ve gotten quite the experience over the years. The mentalities of “too good to be true” and “I deserve” are, unfortunately, at odds, but we remain blind to the tension when it comes to our own actions and decisions. When we see other people talking about their unbelievable deal or crazy good fortune, we realize at once that they’ve been taken for a sucker. But when it happens to us, well, I am just lucky and deserving of a good turn.

And yet, when it comes to the con, everyone is a potential victim. Despite our deep certainty in our own immunity — or, rather, because of it — we all fall for it. That’s the genius of the great confidence artists: They are, truly, artists — able to affect even the most discerning connoisseurs with their persuasive charm. We fall for them because it would make our lives better if the reality they proposed were indeed true.

That, in the end, is the true power of belief. It gives us hope. To live a good life we must, almost by definition, be open to belief, of one form or another. And that is why the confidence game is both the oldest there is and the last one that will still be standing when all other professions have faded away.

From The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It — Every Time by Maria Konnikova. Published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Maria Konnikova.

Maria Konnikova has published articles in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Slate, and Scientific American, among numerous other publications. Konnikova is the author of The New York Times bestseller Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes (Penguin Books, 2013).

On Your Marks!

“There’s a sucker born every minute,” is a quote often attributed to P.T. Barnum. Over the decades, the Post was there to alert readers to common swindles of the day as well as to ponder what it is precisely that makes good, honest people so vulnerable to con men.

How Con Men Get to Us

People who work hard for small pay, see no light ahead, and do not understand how to save are natural chance takers. A few dollars out of a month’s earnings do not matter. They may be risked on the most outrageous gambles, the most impossible speculations. Bets are put down on oil wells in Timbuktu, pirates’ treasure in the Caribbean, the hoard of the temple of Quetzalcohuatl, the gold dust from the loins of El Dorado, under the waters of Guatavita, the mines of the moon, and the pot at the end of the rainbow. The public lends its money in small individual amounts, but enormous totals, to all such fancies and does not often complain if there is no yield. It is not at all difficult to understand the origin of the swindling classes or to see by what means the ranks of defrauders are constantly filled up. Death and prison may take many an earnest worker from the flowery fields of con, but the sources of fresh recruits are fecund and the flow quite copious.

—“Con” by W.C. Crosby and Edward H. Smith, February 14, 1920

Give Suckers a Chance!

The main thing that starts a sucker and makes him stick is an unshakable belief in the correctness of his or her judgment. If a loser, he satisfies himself that conditions went wrong temporarily — never his judgment. For that reason he figures that things are bound to right themselves, and when they do it will be a good laugh on his friends who were timid about going in. His sound judgment must finally prevail.

I really believe it would be a serious deprivation to rob suckers of their opportunities to give somebody their money, and it would make them genuinely unhappy. They don’t want sound businessmen and reformers interfering with their pastimes.

—“The Psychology of the Sucker” by Bozeman Bulger, April 15, 1922

Dangerous Dreams

She was a gangling, open-mouthed, vacant-eyed young thing, with untidy hair under a bedraggled hat. You would have supposed her foredoomed to the last degree of pinched and listless obscurity. Yet she had been discovered. Inspired by an advertisement, she had contrived an ungrammatical string of vapid words, two of which came near rhyming; and she bore in her unlaundered hand a long, typewritten letter — evidently a stock form — on a finely engraved letterhead, announcing that her beautiful poem had been accepted. One of the company’s most gifted musicians, it said, was even then composing appropriate music for it. The company felt certain the song would have an enormous success; but she was to remit $25 by return mail — merely to cover the cost of making the plates from which it was to be printed.

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Leslie Jones Collection

It is a sweet thing about this democracy of ours that, however poor and humble and generally hopeless one may be, some genial thief is doing his best to reach one and swindle one out of the little one has.

—“Inclusive as the Air,” Editorial, July 29, 1922

The Ponzi Principle

Though the principle of fraud is very old, it assumes new disguises from time to time. Charles Ponzi began his operations in June 1920 with about $200. His business amounted to $14 million by July of that year, and the crash came in August. The business grew rapidly because the credulous persons who invested their money in the scheme expected a return of 50 percent in 45 days. The operations were based upon the theory that profits could be made in international reply coupons — a postal medium by which international relations in postal finance are simplified. For a short time even persons versed in finance were puzzled. “But how shall I know the false from the true?” asks the investor. There is, of course, no simple or single answer. Luck plays a part, but common sense, good judgment, that indefinable yet essential quality known as discrimination, patience, courage, and reasonableness also come into the picture. No wonder so many people lose money!

—“Age-Old Fraud,” Editorial, May 4, 1929

This article is featured in the January/February 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for this article. What puzzles me is that so many of our countrymen were gullible enough to elect a con artist to the presidency. And many, far too many, still embrace the scam of legitimacy.