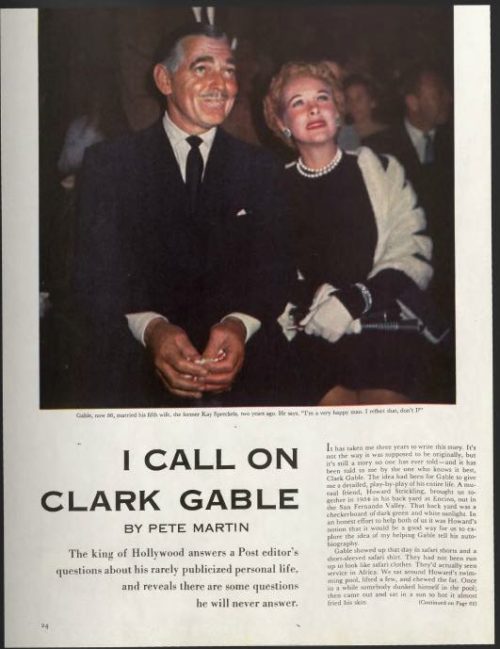

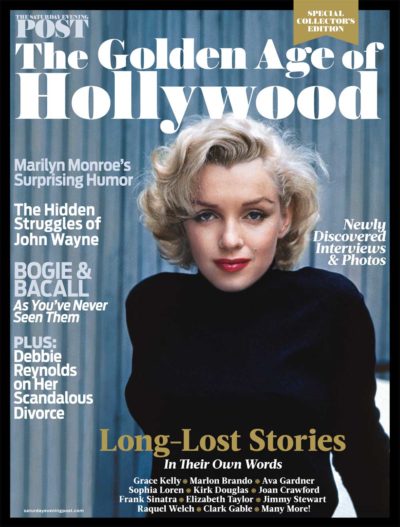

This article was originally published in the Post on October 5, 1957. This and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood, which can be ordered here.

My wife, Kay, is stopping by at 3 o’clock to pick me up,” Clark Gable told me when he walked into my hotel room for our interview. “You ask me questions, and I’ll tell you the truth. If you ask me something too personal, I’ll say, ‘that’s a question I don’t care to answer; I’m keeping that to myself.’ But if you ask me something that I feel I can answer honestly, I will.”

After I’d tried unsuccessfully to ask him a few personal questions, I asked him about three pictures he’d been in: IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT, MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY and GONE WITH THE WIND. “I’ve heard you wanted to be in none of them,” I said, “but in each case somebody talked you into changing your mind.”

“IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT came along early in my motion-picture career,” he said. “For two years after M-G-M put me under contract, I pulled guns on people or hit women in the face. Then M-G-M assigned me to a bad part in DANCING LADY, with Joan Crawford—a picture I didn’t like. But as bad as the part was, it wasn’t as bad as my health.”

“What was wrong with you?” I asked.

“I’d lost a lot of weight. They’d been working me hard, and I was tired. I told myself, ‘If I have a few operations, that will take care of my health and the part in DANCING LADY too.’ I had my appendix and my tonsils out, but it didn’t take care of everything, for M-G-M was mad at me. For some strange reason they thought I’d taken evasive action to avoid their picture. They bided their time during the eight or nine weeks I was in the hospital. Then the very day after I got out they called me in and said, ‘We’re sending you over to Columbia Pictures on a loan-out.’”

“Was that punishment?” I asked.

“At that time Columbia was on the wrong side of the tracks,” Gable said, “and being sent there was a this-will-teach-you-a-lesson deal. I didn’t know anybody at Columbia, but I’d been told, ‘Report to Frank Capra,’ so I reported to him.

“Frank is a nice guy, and he was tolerant of my attitude, which, to put it mildly, wasn’t good. He didn’t know I felt that I had just been swept out of M-G-M’s executive offices with the morning’s trash. I took home the script of IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT, and I read it. I had a couple of drinks and thought, It can’t be that good. I’d better look at it later. So I had dinner and read it again. It was still good. The next morning, I called Frank and said, ‘I want to apologize for my behavior yesterday. I was rude, and I had no reason to be. You’ve got a fine script. Why you’ve chosen me to be in it I don’t know. You’ve never seen me play comedy on the screen.’”

“Did he ever tell you why he chose you,” I asked.

“I don’t know to this day,” Gable said. “I told him, ‘If you think I can do it, I’ll try, but after three or four days, if you don’t like what you see on the screen, you can call the whole thing o and there’ll be no hard feelings.’ We worked a few days; Frank came to me and said, ‘We’ll have no trouble.’”

In the end, the lm’s female star, Claudette Colbert, and Gable himself won Academy Awards for the year’s best performance by an actress and actor. The picture itself won the award as the outstanding production of 1934. Capra won an Oscar for his direction. Writer Bob Riskin won a similar award for the year’s best screenplay.

Other Roles Nearly Missed

“I didn’t want to be in the second picture you mentioned, MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY, because it was a story about

a crew of Englishmen, and since I obviously wasn’t English, I felt I was badly miscast.

“For a while there was a deadlock. It was broken by Kate Corbaley, who headed M-G-M’s story department. God rest her soul—she’s dead now—but she was a wonderfully kind, white-haired, brilliant woman. She knew I was giving Irving [Thalberg, one of the film’s producers,] a bad time, and she didn’t like civil war in the studio, so she came to me and said, ‘I think you’re making a mistake. I’ve read this story, and I can’t see anybody else playing Fletcher Christian but you.’

“‘Not me, Kate,’ I said stubbornly. “I’d have to wear knee britches and a three-cornered hat. That’s more than I can stomach.’

“‘Don’t be such a mule,’ she told me. ‘Listen.’ So I listened, and after I listened, I said, ‘O.K., let’s go,’ although I still didn’t like it.”

“Did you feel better about it as you went along?” I asked.

“Not me,” he said. “I told everybody who’d listen, ‘I stink in it.’ I didn’t realize I was wrong for several months. But after the studio previewed MUTINY, I got a cablegram from Thalberg: ‘The movie is wonderful. We’re proud of it. You’ll like yourself in it.’ I had to believe Irving because he was a guy you could believe. He didn’t kid himself or anybody else.”

“I don’t see how you could have avoided playing Rhett Butler in GONE WITH THE WIND,” I said. “The whole country cast you in it long before the cameras began to roll.”

“That was exactly the trouble,” Gable clarified. “Not only that but it seemed to me that the public’s casting of me was being guided by an elaborate publicity campaign.”

I disagreed. “That casting was a natural thing,” I said. “No studio or producer controlled it. I sat in any number of bull sessions in friends’ homes while we cast that picture. Nobody said we ought to cast it; we just did. And the way we nonmovie employees cast it was the way it was eventually cast on the screen. Almost everybody agreed on you as Rhett Butler, Leslie Howard as Ashley and Olivia DeHaviland as Melanie.”

“My thinking about it was this,” Gable told me, “that novel was one of the all-time best sellers. People didn’t just read the book; they lived it. They visualized its characters, and they formed passionate convictions about them in their minds. You say a lot of people thought I ought to play Rhett Butler, but I didn’t know how many had formed that opinion.”

“Enough,” I said.

“There are never enough,” he told me. “But one thing was certain: They had a preconceived idea of the kind of Rhett Butler they were going to see, and suppose I came up empty?”

I’d never heard that phrase before, so he explained, “I thought, All of them have already played Rhett in their minds; suppose I don’t come up with what they already have me doing. Then I’m in trouble. If they saw one thing I did that didn’t agree with their remembrance of the book, they’d howl. I’d done the same thing when I’d wanted to be a Shakespearean actor. I’d taken a copy of HAMLET or RICHARD II or OTHELLO to the theater with me, and I’d checked on the Shakespearean actors. I’d say, ‘Why that — missed an “and” or ‘He left out a “but.” He can’t do that.’”

“I’ve seen GONE WITH THE WIND three times,” I told him, “and I had the feeling you enjoyed it.”

“It was a challenge,” he said. “I enjoyed it from that point of view. But my chin was out to there. I knew what people expected of me and suppose I didn’t produce?”

“But you did produce,” I said.

“Maybe so,” he said noncommittally.

“When did you finally get it through your head you’d done all right?”

He said, “The night we opened in Atlanta, I said, ‘I guess this movie is in.’”

“How did you figure that?” I asked. “Did you enjoy it yourself or did you gauge it by other people’s reactions?”

“Other people’s reactions,” he said.

I said, “Have you ever considered retirement? What do you think about your future?”

“That’s a logical question, and I’ll give you a logical answer,” he said. “When the public doesn’t want me any longer, I’ll quit.”

“How will you know?” I asked.

“I don’t want to stay around long enough to bore people, and I won’t. They have their own way of expressing themselves, and unless an actor is looking the other way, he can see the warning. But as long as the people still go to see my films, I’ll do my best to entertain them.”

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood, which can be ordered here.

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood, which can be ordered here.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now