On September 4, 1888, George Eastman received a patent for a camera that used his dry-plate technology on celluloid film. Until Eastman came along, photography was a cumbersome and expensive business. Images could only be captured on wet photographic plates, which had to be made up on the spot and immediately used.

Eastman needed a trademark name for his film and cameras that was short, unique and memorable, and used his favorite letter: “k.” “Kodak” was the result.

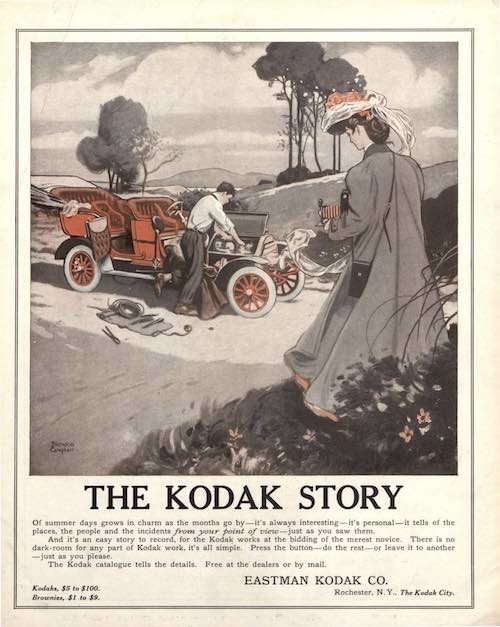

These advertisements that appeared in the Post show not only the evolution of Eastman’s cameras, but also changes in advertising from 1901-1965.

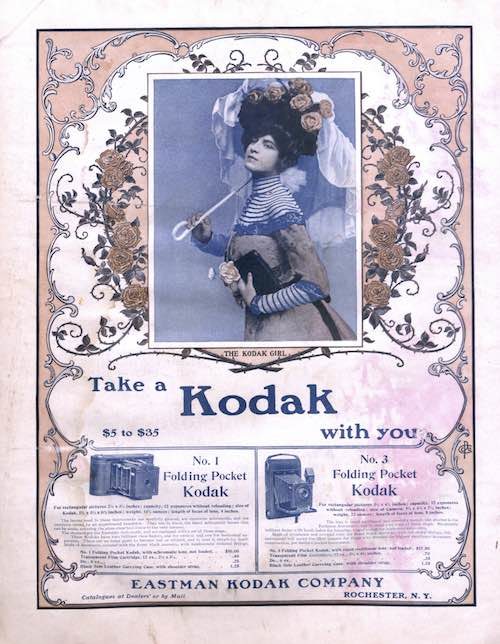

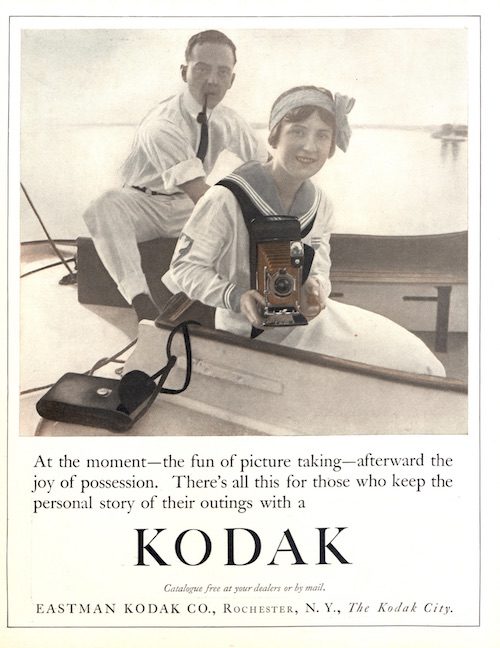

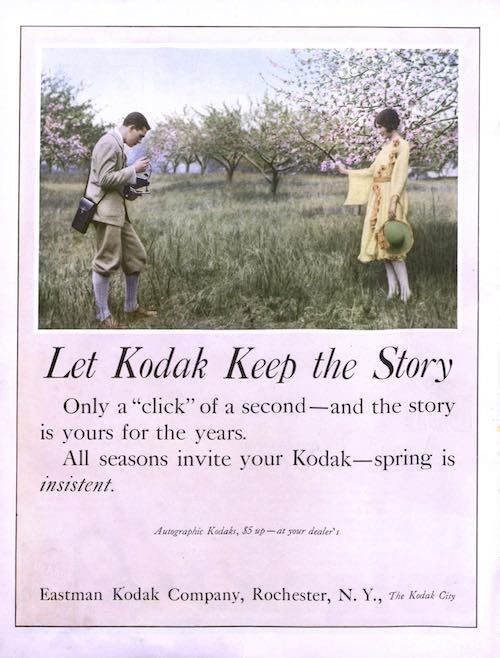

Kodak was a frequent advertiser in the Post. Here is one of its first full-page ads. Note that the Kodak ads showed women using the camera more often than men. Eastman wanted to emphasize that his cameras were extremely portable. Unlike the heavy, awkward bellows cameras of professionals, they didn’t require a lot of muscle to move around. Also, women represented a promising new market.

Kodak’s convenience would profoundly affect American society by making photography accessible to average Americans. They could photograph ordinary objects and commonplace activities that might never have been recorded by professional photographers.

Originally, users were required to mail their camera, with its exposed film, back to the company, which would remove and develop the film, then return the camera loaded with fresh film.

Owners of Eastman’s cameras and film could take pictures on a whim, which enabled them to photograph their friends looking relaxed and natural — a far better reflection of personal character than a formal portrait.

This ad might have implied color photography, but Kodak wouldn’t introduce its Kodachrome color film for another nine years.

In previous wars, soldiers had carried formal photographic portraits of their wives, sweethearts, or families. By World War II, they would get recent snapshots that showed how the folks back home looked and what they were doing.

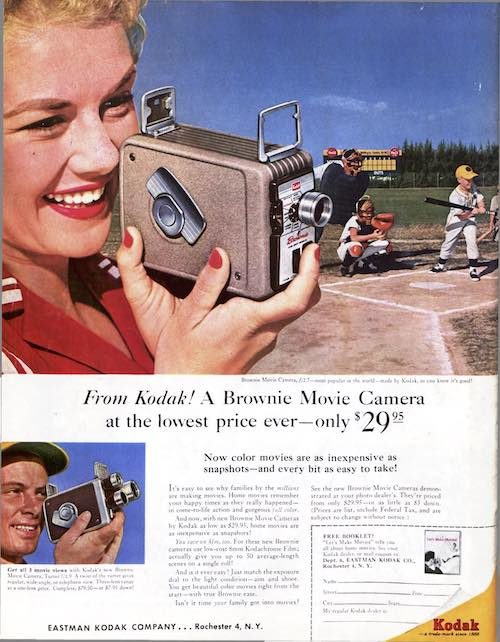

The dry film concept had also led to motion-picture film. Throughout the century, the cost of movie cameras kept dropping into more affordable price ranges.

By 1961, Kodak cameras could automatically set the correct exposure. They also allowed convenient indoor photography with flash bulbs. And all for $22, the equivalent of $179 today.

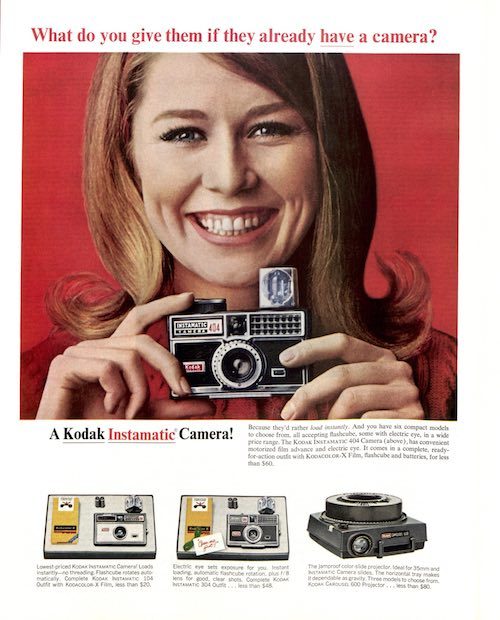

Cameras kept getting smaller, and flash photography now used flash cubes. They let you take four indoor pictures without changing flash bulbs. A motor would automatically advance your film for the next exposure.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I love all of these ads, but the 2nd one in particular by Blendon Campbell; fantastic! He did ads for Ivory Soap too, but his regular ‘art art’ is out of this world. He’s right up there with Coles Phillips and Maxfield Parrish.

The next two ads are charming too. The 1942 ad really shows the importance of snapshots in keeping the soldiers up to date on what was going on at home. The last 3 show are great also. I remember that Instamatic camera coming out at that time in 1965. It was a big deal, and my mother loved it!

For the rest of the century not depicted here, photos and photography really meant something. It still can, and does, but since the mid-2000’s has largely been reduced to meaningless cell phone selfies and of people documenting every little thing throughout the day, everyday.

Meanwhile the color in movies/films has really devolved in the digital age. “Blue and white” isn’t my thing at all. Not a problem since I rarely see any films that are not in limited release. The only ‘explosions’ I’m interested in is in the dialog between the characters, thank you!