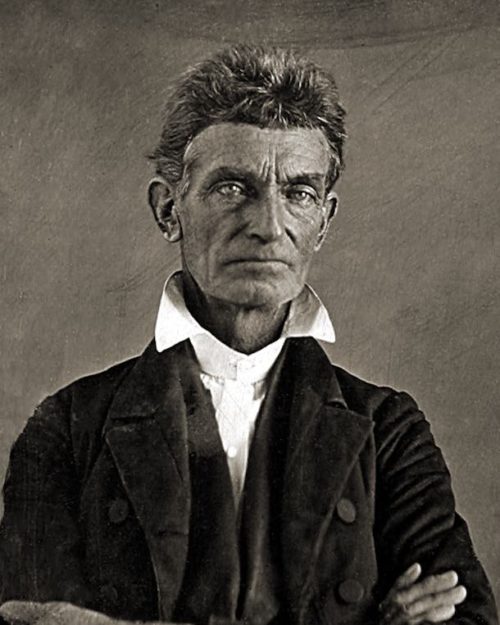

John Brown was an abolitionist in the mid-1800s who believed that violent confrontation was the only way to overthrow slavery in the United States. His raid of the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, 158 years ago today, on Oct 16, 1859, is widely acknowledged to be one of the major triggers of the Civil War.

Before the raiders were finally subdued by a force led by Col. Robert E. Lee, seventeen people were killed–two slaves, three townsmen, a slaveholder, one Marine, and ten of Brown’s men. Another ten were injured.

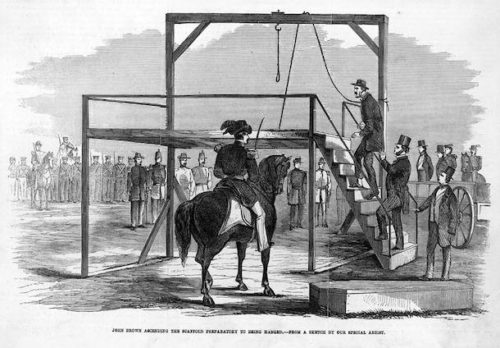

Southerners viewed Brown’s actions with fear and shock. They believed that arming slaves and inciting them to rebel was nothing more than terrorism. Many northerners agreed. Brown was swiftly put on trial for treason. When he was hanged on Dec. 2, 1859, he handed a note to a guard with these words: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”

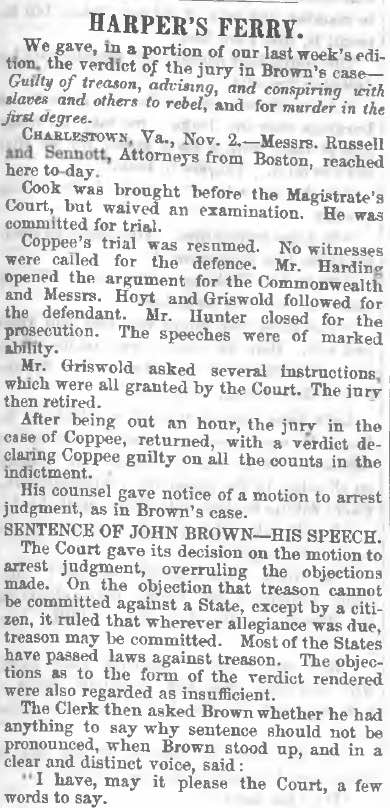

The Harpers Ferry raid galvanized the nation, but Brown’s final address to the court, which was published in The Saturday Evening Post and other Northern newspapers, helped convince many that he was a martyr for freedom and not simply a violent criminal.

John Brown’s address to the court, published in The Saturday Evening Post on Nov. 12, 1859:

I have, may it please the Court, a few words to say.

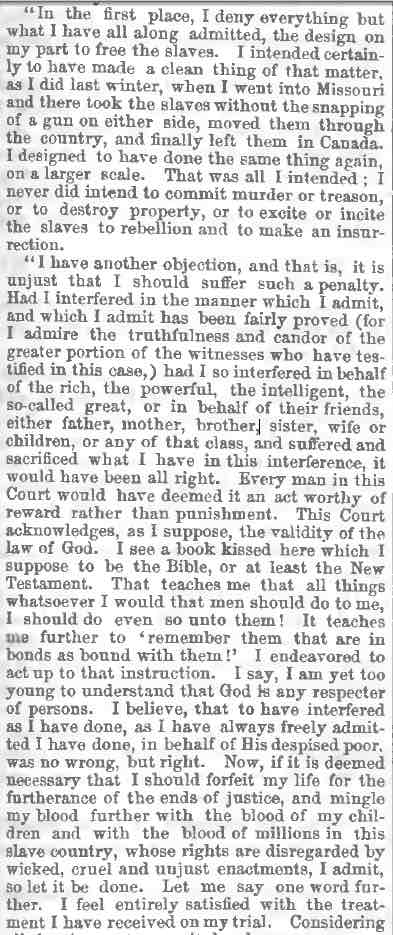

In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted, the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri and there took the slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada.

I designed to have done the same thing again, on a larger scale. That was all I intended; I never did intend to commit murder or treason, or to destroy property, or to excite or incite the slaves to rebellion and to make an insurrection.

I have another objection, and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case,) had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right. Every man in this Court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment. This Court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so unto them! It teaches me further to ‘remember them that are in bonds as bound with them!’ I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe, that to have interfered as I have done, as I have always freely admitted I have done, in behalf of His despised poor, was no wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country, whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I admit, so let it be done.

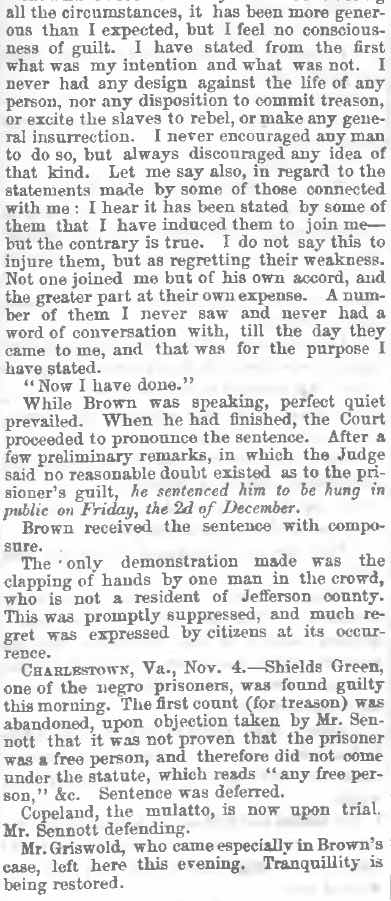

Let me say one word further. I feel entirely satisfied with the treatment I have received on my trial. Considering all the circumstances, it has been more generous than I expected, but I feel no consciousness of guilt. I have stated from the first what was my intention and what was not. I never had any design against the life of any person, nor any disposition to commit treason, or excite the slaves to rebel, or make any general insurrection. I never encouraged any man to do so, but always discouraged any idea of that kind. Let me say also, in regard to the statements made by some of those connected with me: I hear it has been stated by some of them that I have induced them to join me— but the contrary is true. I do not say this to injure them, but as regretting their weakness. Not one joined me but of his own accord, and the greater part at their own expense. A number of them I never saw and never had a word of conversation with, till the day they came to me, and that was for the purpose I have stated.

Now I have done.

Read the Post’s coverage of John Brown’s speech as it appeared in the November 12, 1859, issue.

Featured image: “The Tragic Prelude” by John Stewart Curry, United Missouri Bank of Kansas City, Wikimedia Commons

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now