Zombies have officially taken over pop culture. The shambling, flesh-craving living dead have steadily moved through film, television, and literature until they’ve become one of the primary vehicles for delivering scares. You see them in the bookstores in the works of authors like Max Brooks and Brian Keene. You find them in comics without number. You’ll watch them on television programs like the comic-derived The Walking Dead and SyFy’s Z Nation. Fifty years ago this week, their rampage began when the dead crawled out of the grave under the watchful eye of an enterprising group of Pittsburgh filmmakers. This is how Night of the Living Dead came to life.

New York-born director George A. Romero graduated from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh in 1960. He was soon directing short films and ads. He even directed the famous bit from Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood in which Mister Rogers got his tonsils out.

Writer John A. Russo went to West Virginia University, but met Romero through a mutual friend. After two years in the U.S. Army, Russo returned and joined Romero and actor/producer Russell Streiner in the filmmaking collective The Latent Image. After working together for a while, the trio decided to do a horror film and, with the addition of other talent, created production company Image Ten.

Russo was working on a story that involved kids, a graveyard, and aliens with a taste for human flesh. He says, “George came in about that time with about 30 pages of a story that had a man and his sister putting a wreath on their father’s grave when they get attacked. It was in essence what became the beginning of NOLD.” Russo pointed out that it could be the dead attacking the girl, and Romero was amenable. When it came to the idea of motive, Russo had that covered: “So I said, “Why don’t we use my flesh-eating idea?” So that’s how they became dead people after human flesh.”

The ten members of Image Ten each invested $600 into the film; they would eventually raise $114,000 for the budget. Filming commenced in June of 1967. For the role of the female lead, Barbara, Romero and company cast Judith O’Dea. She came to the project through Karl Hardman, the Image Ten member that would take the role of Harry Copper. O’Dea says, “It was Karl who called me back from Hollywood where I’d moved in 1966 hoping to break into film and TV. ‘How would you like to audition for a horror film George Romero and a bunch of us want to make?’ he said. With no second thoughts, I jumped on the first plane home, and, as they say, the rest is history.”

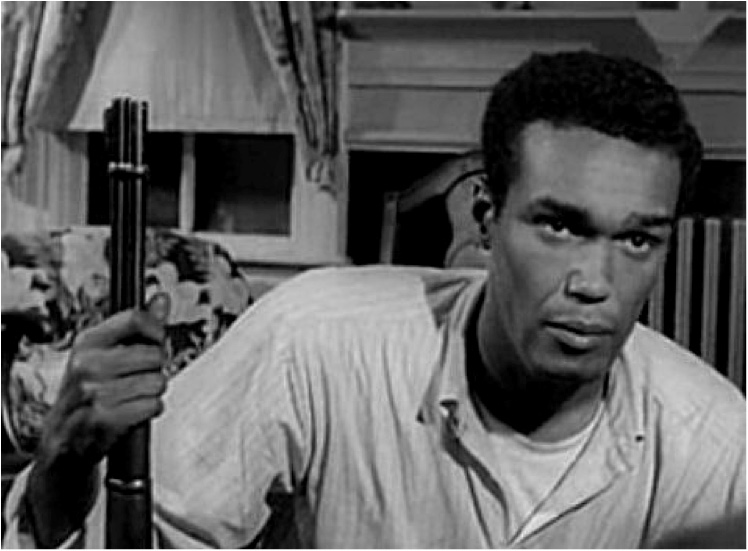

Duane Jones played the male lead, Ben. Jones had attended the Sorbonne and also studied acting in New York. While Romero would later say he simply cast the best actor for the part, it was a bold move in 1967 to cast a black man as the lead; that was a first for an American horror film. Perhaps more remarkably, screenwriter Russo and director Romero made no fundamental alterations to the script or story to reflect the fact that Ben was an African-American protagonist; he shows up acting heroically from the start, with no direct comment on his appearance occurring at any point in the film.

The film opens with O’Dea’s character, Barbara, and Streiner’s character, Johnny, visiting their father’s grave out in the country. After Johnny attempts to unnerve his sister with the famous line, “They’re coming to get you, Barbara,” the pair are attacked by the first of many zombies to come. That remains one of O’Dea’s most memorable moments from filming. She says, “One of my indelible memories of our movie making is how truly frightened I became while being attacked and chased by our #1 ghoul, Bill Hinzman. He set the bar for the decades of zombies to come.”

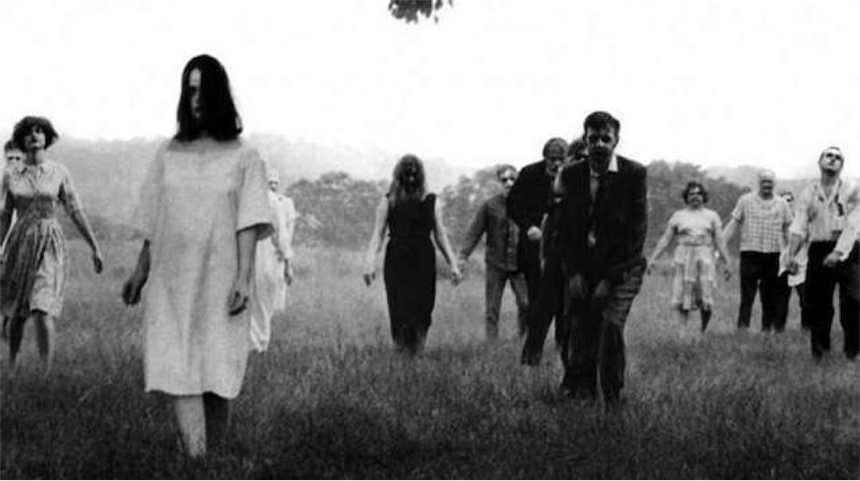

From there, the film plunges into a nightmare scenario of the newly dead rising from the grave in search of humans to consume. A group of survivors holes up in a farmhouse under siege by the living dead. The tension inside escalates along with the danger from the outside.

Critics and scholars have commented on Romero’s expert creation of tension. Writing for Slant on the occasion of the film’s 40th anniversary, Jeremiah Kipp said, “The frequently handheld camerawork doesn’t quite feel like documentary photography, but it does lend a sense of immediacy and tension right from the start.”

The film also shoves the viewer straight over the taboo line, indulging as it does in scenes of gore, cannibalism, and matricide that hadn’t been as graphically depicted on film. Queen of Blood director Chris Alexander says, “It was a film that clicked on every level, from script to cast to unflinching, cinema verite sheen, and even at its most repellent, the violence and shock have a raw, emotional component that no one had seen in an American horror picture. And it was made by unknowns, seemingly blasted out of another dimension, making the entire thing feel authentic, real.”

When the film came out, it had a deeply polarizing effect. The October 1, 1968, premiere was on a Saturday afternoon, which wasn’t that odd for a horror film at the time. There was no MPAA rating system at the time, and young people were able to buy a ticket. Film critic Roger Ebert reported in the Chicago Sun-Times that the audience didn’t know what hit them; although he was critical of the system that let young kids in, he professed his admiration for the skill of the filmmakers. Ebert’s fellow legendary critics Pauline Kael and Rex Reed also went to bat for the film, both citing it as “terrifying” in the best cinematic terms. Variety went another direction, calling it “pornography of violence.”

Over time, the film has only grown in reputation and critical standing. Its influence is cited by a veritable legion of artists. Zombies continue to be popular in novels like World War Z by Max Brooks and The Rising by Brian Keene. Hugely successful filmmakers like Zack Snyder and James Gunn worked together on the 2004 Dawn of the Dead remake. One such admirer is Tony Moore, the co-creator and original artist of the comic book, The Walking Dead, which serves as the basis for the hit TV franchise. Moore appreciates how the film is instructive about human nature. He says, “The zombies are fun and everything, but really they’re a pressure cooker for the survivors, and it brings out the monster in them. It makes us as a viewer do a little self-examination and wonder “How would I fare in a survival scenario? Would my moral compass change when the laws of the land were thrown out the window?”

Moore also hits on another area of critical focus: that the film serves as a microcosm of other social issues. He says, “It’s also a fantastic little time capsule on the worries of the day, all swirled together. Vietnam was making us consider the high cost of our hawkishness. The Cold War had everyone considering an apocalypse scenario.”

The importance of Ben’s role as the hero also stands out for Moore, particularly when it comes to his tragic fate. Moore says, “The Civil Rights movement showed us the horror of how we treated each other right here at home. Ben, the movie’s African-American lead, manages to narrowly survive the ordeal, only to be shot down by the people who were supposed to be rescuing him, and burned with the rest. It’s bleak. It’s biting. It’s simple, but powerful, as much today as ever.”

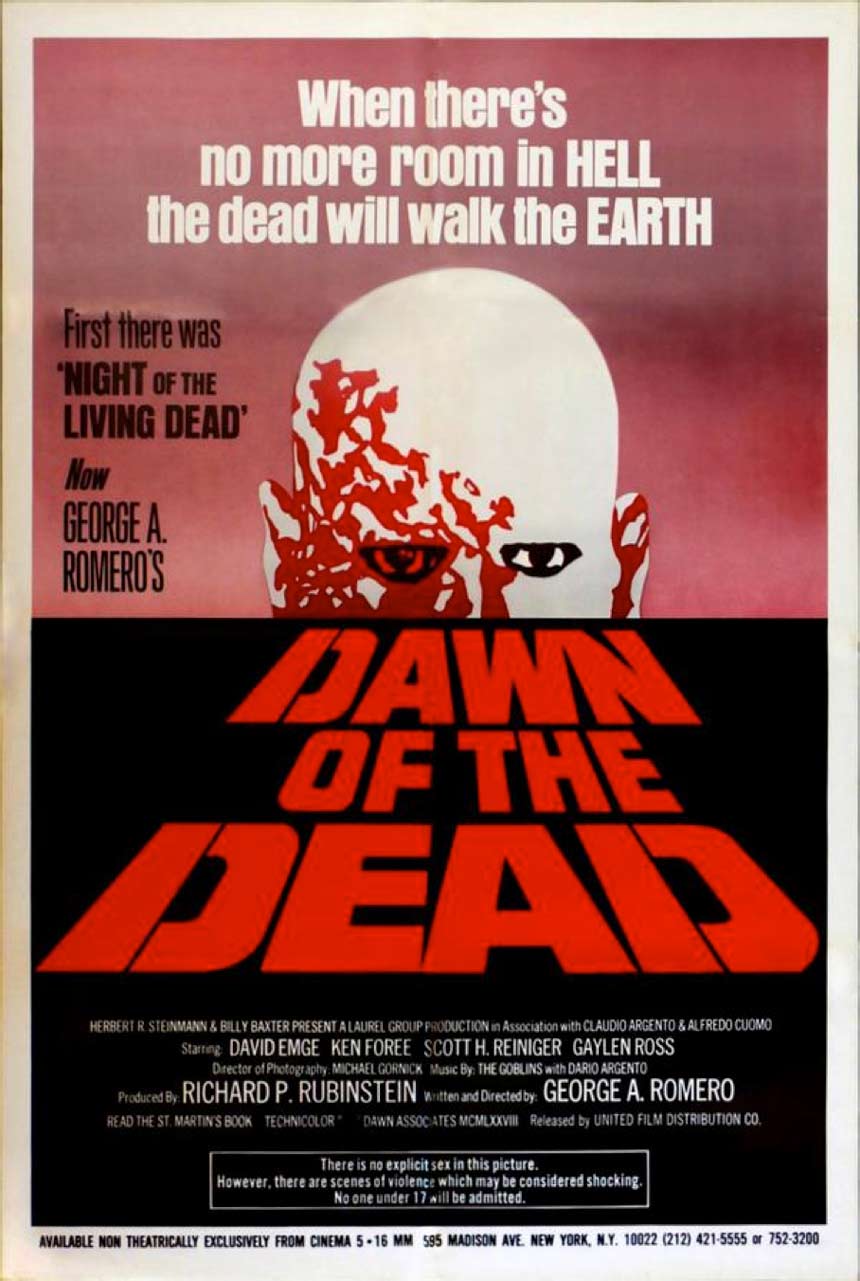

Director Chris Alexander also counts himself as a dedicated admirer and one whose career has been shaped by the film. He says, “Night of the Living Dead and its sequel Dawn of the Dead, set me on a course of thought and idea and sparked an intellectual interest in cinema. They leveled me viscerally and haunted me and naturally, as I aged, obsessed me.” Moore acknowledges the huge influence that film had on The Walking Dead. He says, “Romero built our stage, we just managed to use those tools to tell a story that resonated with modern audiences. I could never repay the eternal debt of gratitude I owe George Romero.”

The film’s importance has been celebrated in a number of ways over the years. Last year, Night of the Living Dead was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry, as a film considered “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” It also took a little while for the significance of the film to sink in for O’Dea. She says, “That didn’t happen until I returned to Pittsburgh to celebrate the film’s 25th anniversary [in 1993]. So many fans were there dressed in all kinds of zombie outfits. I was blown away, and quickly began to realize that those wonderful people were creating a place in film history for NOTLD.” For his part, Russo knew they were on to something when they were making the picture. He says, “We had complete confidence that we were making a good movie, and we were totally behind George Romero as the director, and he did one hell of a job! We all did!”

Due to its public domain status, the entirety of Night of the Living Dead is available on YouTube.

Due to a fluke involving an early film transfer, the copyright notice was left off of the original film. That means that Night of the Living Dead has been in public domain basically from the beginning. So there are hundreds of versions of the film across home media platforms, including over 200 versions on DVD around the world. Most of the home media presentations do contain the original version. In 1999, Russo made Night of the Living Dead: 30th Anniversary Edition, which added newly shot footage and situations to the original film, along with a new soundtrack.

Romero and Russo continued to build zombie cinema in the decades to follow. Though a dispute led them to split later on, they forged an agreement where Romero’s films would have “of the Dead” in their titles, and Russo’s would contain “Living Dead.” Therefore, Romero made a number of further “Dead” films, including Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead, while Russo went on to make the popular Return of the Living Dead series, among others. The movie also continues to count as a huge influence on independent filmmakers, as its emblematic of what a tight, committed group can do with limited resources as long as they have the drive to commit something of quality to film. Upon Romero’s passing in 2017, he was celebrated by media around the world as an influential figure in entertainment and honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

It’s perhaps suitably ironic that a film about the living dead seems destined to live forever. For O’Dea, she feels the effects of the movie in a unique way, as she’s had fifty years of people telling her, “They’re coming to get you, Barbara.” When asked about how often she’s heard it, O’Dea says, “How many zeros does it take to make a ga-zillion?! But no matter how many, I will NEVER tire of hearing that line.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very interesting, well written feature on ‘Night of the Living Dead’ proving once again, today’s zombie/horror attempts live in the long dark shadows cast by the 1960’s—–just like everything else. The more time goes by, the longer the shadow will only get, naturally. I’ve always been a fan of this film, and loved the clever episode of ‘Medium’ from 2009 where Patricia Arquette (through technology) inserts herself into the ’68 film, fitting right in. In another interesting twist, that’s the year she was born!