This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The celebration of Thanksgiving offers Americans a chance to consider some of the earliest post-contact histories of this land. While there are many myths associated with the story of the “First Thankgiving,” that 1621 harvest celebration genuinely connects us to early American histories that we all celebrate.

In the case of Tisquantum (Squanto), a Patuxet Wampanoag Native American whose story famously intersected with that of the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving, remembering his life highlights the horrific effects of early racial divides and models the possibilities of an inclusive America.

Tisquantum’s post-contact story (his life before European contact is largely unknown) begins with kidnapping and enslavement. English explorers began enslaving indigenous people in the earliest years of English arrival to the Americas, well before there were English settlements in places like Massachusetts (where Tisquantum’s Patuxet tribe resided, on the western coast of what would come to be known as Cape Cod Bay). Explorers such as Captain George Weymouth kidnapped Massachusetts natives as early as 1605, and over the next decade the practice became common.

Tisquantum was enslaved in 1614, when Thomas Hunt, an English explorer traveling with Captain John Smith on his trading expedition to New England, kidnapped 27 local natives and transported them to Spain, where he sold them into slavery. The next few years in Tisquantum’s life are once again mostly lost to historians, but at some point he made his way to England and from there to a new English colony in Newfoundland, where he was sent as a slave (or perhaps by this time a servant, although in either case he likely had no say in the matter).

Around 1619, an English member of that colony, Thomas Dermer, brought Tisquantum back to New England, where Tisquantum learned that the rest of his Patuxet tribe had met a tragic end, destroyed by one of the many epidemics that Europeans brought to the Americas as an accidental complement to their more intentional genocides.

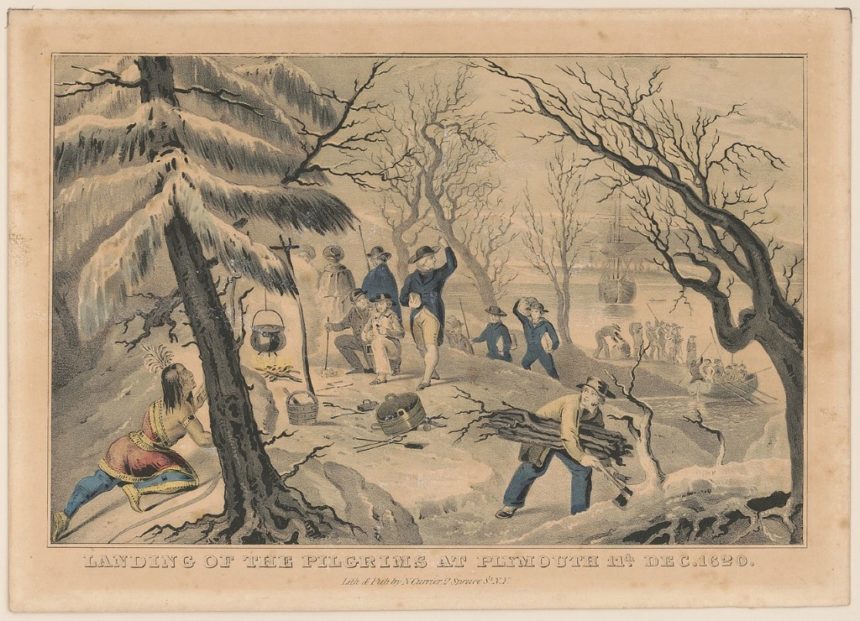

Left without a home or community by European devastations both personal and global, Tisquantum went to live with a neighboring Cape Cod tribe, the Pokanoket Wampanoag. At this point, it would have been entirely understandable if he had wanted nothing more to do with Europeans, or even had become overtly hostile to any such further contacts. Yet a year or so later, when the Mayflower arrived off of Cape Cod in November 1620 and the Pilgrims settled at nearby Plymouth, quite close to the site of the Patuxet tribe’s former summer village, Tisquantum decided instead to take on a potent cross-cultural role. He befriended and aided the English, worked to bring together the English and native cultures (despite suspicions of his motives from both sides), and modeled an inclusive New England and American community in the process.

A number of factors likely played into that surprising decision. Tisquantum’s years of slavery and servitude in Europe and Newfoundland had enabled him to learn English (among other languages), and of course had also prepared him to interact with European communities far more easily than most of the period’s Native Americans. It’s also possible that his position with the Pokanoket was not particularly secure (some historians have even argued that he was treated as a prisoner of the tribe), and that he thus saw the arrival of these European settlers as a chance to prove his value to and make powerful friends within multiple communities. Such a perspective would be understandable and wise for anyone in Tisquantum’s position, much less one with years of tragic experiences in his recent past. And in truth, whatever his motivations—and to see them as complex and even contradictory is simply to give him the humanity that racist narratives would deny him—Tisquantum’s efforts did indeed prove invaluable both to the English and for an emerging, inclusive New England community overall.

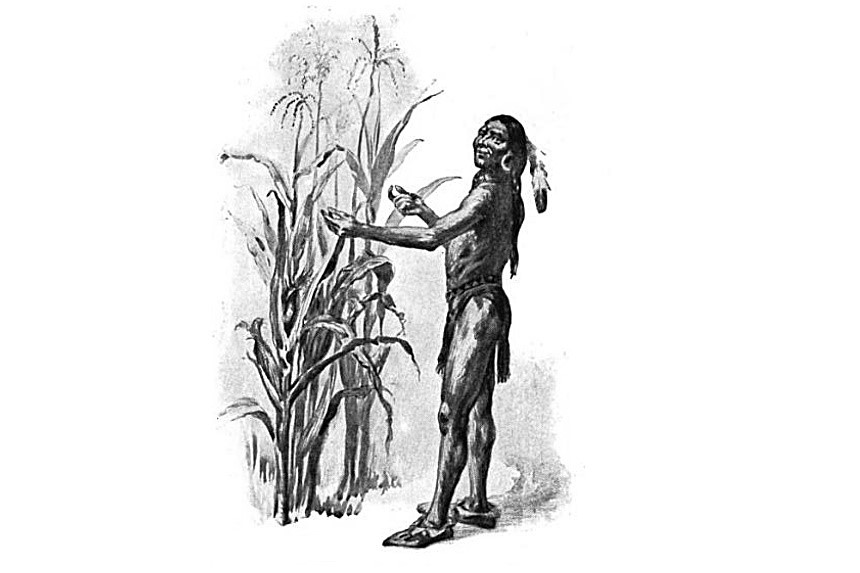

No moment better exemplifies his multi-layered contributions to that community than the “First Thanksgiving.” While the children’s story version of that autumn 1621 event has been often overplayed in our national collective memories, allowing us to forget the much less attractive histories of genocide and enslavement, we shouldn’t respond by swinging the pendulum too far in the opposite direction and downplaying the moment’s significance. For one thing, the Pilgrims had good reason to hold this three-day autumn celebration (it was held sometime between September and November, and they did not call it Thanksgiving): they had brought in a bountiful harvest, and were envisioning a far less horrific winter than the first they had spent in Plymouth. In his account of the celebration for an English audience in his book Mourt’s Relation (1622), Pilgrim Edward Winslow writes, “although it be not always so plentiful, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.” And it was chiefly to Tisquantum, and all that he had taught them of farming and trading in the region, that the Pilgrims owed this crucially plentiful autumn harvest.

For another thing, the Pilgrims hosted honored Wampanoag guests at the celebration. As Winslow describes it, “many of the Indians [came] amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain and others.” This peaceful, cross-cultural gathering was far from a given, as the Pilgrims’ first experiences with the Wampanoag in late 1620 and early 1621 had been far more hostile and violent.

William Bradford, the community’s governor at the time of the harvest celebration, describes two such experiences in Chapter 10 of his communal history Of Plymouth Plantation (written between 1630 and 1651 and published posthumously). When the Pilgrims initially explored Cape Cod, they found a store of food that local natives (a few of whom they had just seen for the first time) had clearly hidden from them, and stole from it:

They found where lately a house had been, where some planks and a great kettle was remaining, and heaps of sand newly padded with their hands. Which, they digging up, found in them diverse fair Indian baskets filled with corn, … which seemed to them a very goodly sight. … So, their time limited them being expired, they returned to the ship lest they should be in fear of their safety; and took with them part of the corn.

Bradford uses a Biblical analogy for this moment, comparing the Pilgrims to Jews in Exodus who “carried with them the fruits of the land and showed their brethren.” Yet these fruits were from the natives, not simply the land, and in making them their own the Pilgrims displayed a similar attitude to that of Columbus taking immediate possession of the islands upon arrival.

Having established their relationship with the local indigenous community on these terms, the Pilgrims should not have been surprised that their first encounter with Native Americans was likewise a hostile one. A group of native warriors attacked the encamped Pilgrims; as Bradford writes, “The cry of the Indians was dreadful, especially when they saw the men run out of the rendezvous toward the shallop [small boat] to recover their arms, the Indians wheeling about them.” It is entirely understandable that the English fought back, but when their superior firepower had chased the attackers away, they defined the experience in overarching and overtly exclusionary terms. As Bradford puts it, “Thus it pleased God to vanquish their enemies and give them deliverance.” When Bradford adds that they “called that place the First Encounter,” we can see how foundational this hostile and exclusionary moment was for the Pilgrims and their perspective on indigenous peoples.

Yet less than a year after these two divisive and hostile events, the Pilgrims and Wampanoags were sharing corn at the harvest celebration. The shift was due largely to Tisquantum, and the six-point peace treaty that he — along with Samoset, a visiting Abenaki tribal leader who had learned English from fishermen near the Gulf of Maine and who served as another mediator between the communities — helped broker between Massasoit’s Pokanoket Wampanaog and the Plymouth Pilgrims. The treaty was practical and political for both sides: the Pilgrims of course needed allies in this new world; and the Pokanoket, themselves decimated by illnesses in recent years, sought protection from the neighboring and potentially hostile Narragansett tribe.

Yet nonetheless this agreement, like the harvest celebration that symbolically cemented it and the cross-cultural mediators who negotiated it, illustrated the genuine possibility of an inclusive New England and American community. It is that community, and the complex but inspiring Native American who helped make it possible, for which we should truly be thankful this and every November.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now