“The long struggle of our flesh and blood to articulate life is still no more to most of us than matter for such idiotic burlesque.” –H.G. Wells

Given that tickets for the Midwestern leg of the national tour of Hamilton: An American Musical start at $400, it would appear that this country has a healthy appreciation of history. More than three years after the immensely popular musical’s Broadway debut, its song-and-dance story of a founding father continues to sell out performances in New York City and across the U.S.

Unfortunately, the popularity of historical theater hasn’t translated to the academic world. Unlike the Richard Rodgers Theatre in New York, college history departments are facing empty seats.

The American Historical Association’s 2018 report on the distribution of undergraduate college majors in the U.S. shows that, since the economic recession, history has faced the greatest decline. Between 2011 and 2017, the number of history degrees awarded dropped more than 30 percent. Since its peak in 1971, the history B.A. has reached its lowest percentage ever as a share of all degrees (.53 percent) even as college attendance has risen. It’s no secret that a history degree, like most degrees in humanities, does not come with a promise of the kind of high salary that many associate with STEM fields. The correlation of students deciding to avoid the major with the economic crisis of 2008 is too strong to ignore.

As other magazines such as Time and The New Yorker have noted, the downtrend of historical studies isn’t ubiquitous. Ivy League schools like Yale, Princeton, and Columbia have growing, robust history programs where students can be sure to find lucrative opportunities upon graduation.

Still, unless we wish to consign this subject to the country’s academic elite, it is necessary that we ask ourselves as a nation about the value we place in understanding our own past. Given recent national conversations around the racist history of blackface and the nature of the Mexican-American border, the value of historians’ in-depth knowledge and analysis in current times couldn’t be clearer. When history is forgotten or skewed, a society is unable to make informed decisions about its future. As the saying goes, “Those who forget their history are condemned to hearing that tripe about George Washington having wooden teeth for all of eternity.”

Are Americans Dumb?

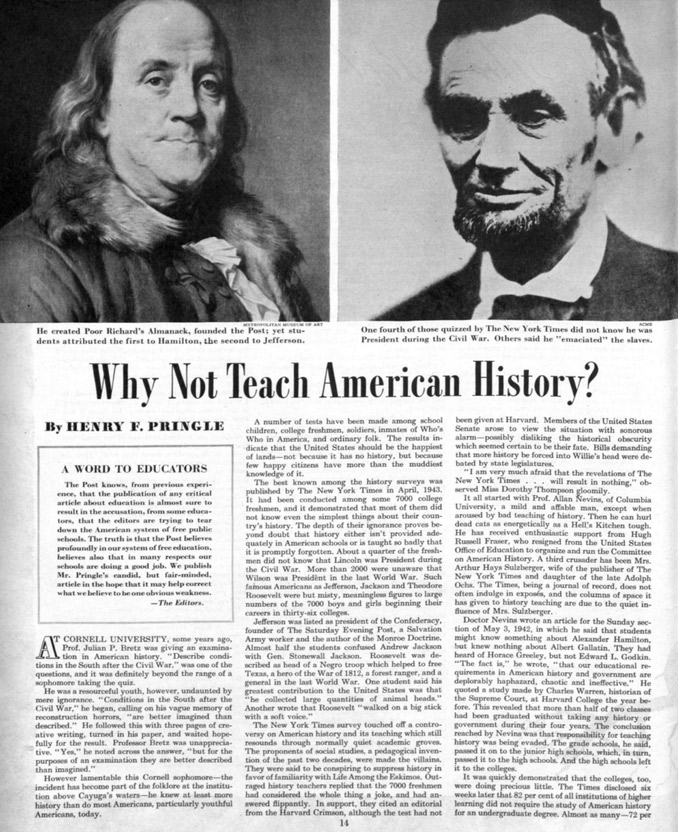

Much has been made of the trope of the uninformed American who couldn’t pass their own citizenship test, name the 13 original colonies, or remember any of Benjamin Franklin’s achievements. The phenomenon of historical ignorance might seem relatively new, but this magazine was reporting on it in 1945.

In “Why Not Teach American History?” Pulitzer Prize-winner Henry F. Pringle made a case for a more comprehensive, engaging study of history in grade school. Citing a 1943 New York Times survey that claimed a quarter of incoming college freshmen didn’t know that Lincoln was president during the Civil War, Pringle declared, “The depth of their ignorance proves beyond doubt that history either isn’t provided adequately in American schools or is taught so badly that it is promptly forgotten.” Pringle was advocating for a more knowledgeable electorate, sure, but he was also promoting a certain type of history: a celebratory one in which a civics education is based primarily on reverence for the American project while denigrating studies of Native Americans, world history, and social studies that he claimed had “greatly diluted history in all its forms.”

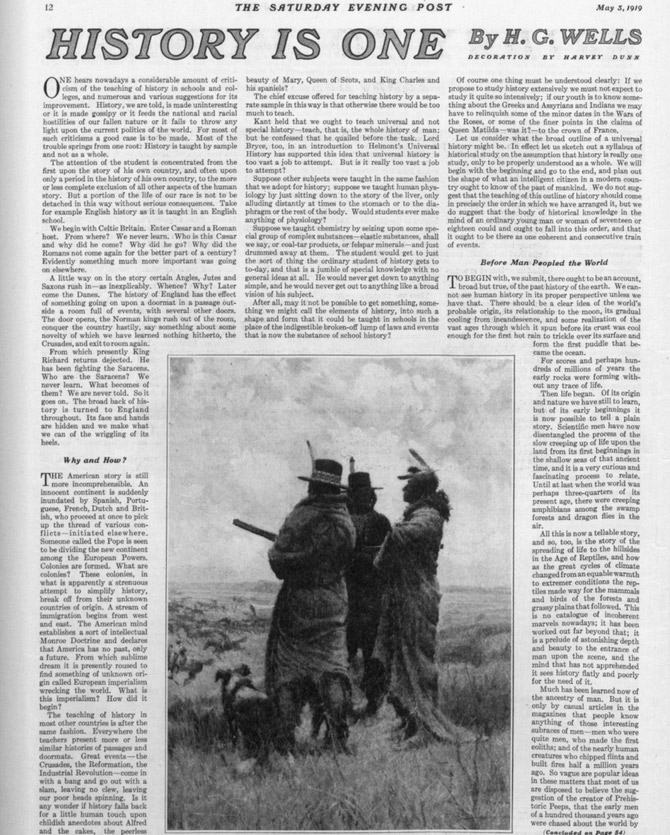

Still earlier, science fiction writer H.G. Wells advocated for a stronger education in history. In 1919, he wrote in The Saturday Evening Post that “One hears nowadays a considerable amount of criticism of the teaching of history in schools and colleges, and numerous and various suggestions for its improvement.” Wells’ suggestion, in his article “History Is One,” was, of course, more history education, but also a different kind: “universal history.” Wells argued that teachers ought to broaden their scope and teach a macro view of human history that could account for the many complicated happenings here and abroad. “We can trace the clash of the early civilizations with the nomad populations about them, see the first beginnings of social classes and the elementary and embryonic forms of all these institutions and all those struggles of class and interest in which we live today,” he wrote. In order that these ideas might be woven into our thoughts from the beginning, Wells urged the teaching of Neolithic peoples, violent conquests, socialism, anarchism, and “the growth of the double idea of a world dominion on the part of the rulers and of a world brotherhood on the part of a driven and distressed and uprooted peoples.”

The kind of history education for which Wells advocated isn’t far off from the view many historians take today. Unlike Pringle’s optimistic perspective of the past, a more critical look at how we arrived at the present may be due.

What History Can Do

“Sometimes when you hear people pushing for a more accessible history, it’s also one that’s mainly celebratory, which leaves too many problems unexamined,” says James Connolly, a professor of history at Ball State University. Connolly is aware of the decline in history degrees, but he is confident about the potential for historians to excel in a variety of capacities. “One of the things that history has done really well and continues to do is to highlight some of the problems and limitations and failures of Americans in the past,” he says, “whether it’s around race or class or gender discrimination.”

Connolly says that the intensive training in reading, writing, and critical thinking prepares history majors for all kinds of jobs like publicists, analysts, and policy-focused professionals, and these types of opportunities should be emphasized by history programs. There is research to back up this claim. Richard Arum, in his book Academically Adrift, observes the differences in Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA) scores between different fields of study. The CLA measures a student’s improvement in critical thinking, analytic reasoning, written communication, and problem solving as a result of attending college. Humanities students (including history majors) scored significantly higher on the CLA (just under science/math students) than students of other fields like health, education, business, and communications, suggesting that they show more improvement in these useful skills over the course of earning a degree.

But what of the highly specific knowledge and skills involved in history studies that aren’t particularly marketable? Should we not roundly encourage the preservation and analysis of our past?

“Universities are not making history a priority,” says Danielle Griego, who graduated last May from the University of Missouri where she studied medieval history. Griego saw a shrinking of the department during her time there that she says was disheartening. She works at The State Historical Society of Missouri, and she says that she feels conflicted when young people ask her about pursuing a history degree. “I want to tell them to do it because that’s what they love,” Griego says, but she finds that the most responsible advice is to at least encourage them to have a backup plan. Griego is a big advocate of public history, the field of work that involves museums, historical societies, preservation, and other ways of bringing history to the wider public. The academic world can be stuffy and inaccessible, so Griego is passionate about making her subject of expertise (although not necessarily the Black Death specifically) approachable to all: “I always wanted to be in public history because I felt I could reach more people in and out of the classroom and show them how the present was shaped.” She was inspired to study history by Indiana Jones.

A More Public History

The scope of public history’s potential is beginning to take shape. In late March, the National Council on Public History will hold its national conference in Hartford, Connecticut, where Samuel Colt started Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company in 1855. For more than a decade, the National Park Service has been working to transform a part of the “Coltsville” neighborhood into a park that could tell the story of arms manufacturing in the Connecticut River Valley as well as the assembly line practices pioneered by Colt’s factories. In discussions at the NCPH’s conference, it won’t be lost on attendees that Sandy Hook Elementary School, where 20 young children were shot in 2012, sits only 40 miles away. The conversations around the history of weapons manufacturing in relation to gun violence are apt avenues for public history, according to Stephanie Rowe, the executive director of the National Council on Public History.

She says the field of public history has been around for centuries; only in the last 40 years or so has it been defined as such. This lines up with the last crisis in history academia, when history degrees dropped 66 percent from 1969 to 1985 before recovering significantly. “There was a crisis in the academic job market,” Rowe says, “and academic historians started thinking about alternative career paths and other ways to think and talk about this work that we’re doing.”

Rowe is all too familiar with the current decline in history academia, but she says graduate public history programs have actually been growing in the last 10 years. She — and others in the field — are excited about how rapidly advancing technology can intersect with historical work to preserve and interpret a legacy in tandem with the public. Along with digital skills, Rowe says the future of public history, and academic history, will rely heavily on funding: “There needs to be advocacy to make sure that potential employers are funded well enough that they can be hiring and paying livable wages.”

The movement of historians to carve out more viability for their field is a balancing act between marketing the sexiness of history and maintaining strict academic integrity. Connolly, the Ball State history professor, cites some historians that have built followings online arguing against falsehoods and misconceptions, like Kevin M. Kruse and Eric Rauchway. Another career that has seen growth is that of historical consulting. Flexible experts can offer advice in various projects and industries, from land use to document management to media, like Hamilton. “The current moment — with all of these debates about American identity and inclusion — seems pretty ripe for historians to step in and weigh in on these public debates,” Connolly says. “Maybe in doing so they could reestablish history as a more attractive discipline with broader prospects.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Interested in learning more about history.