Ever since 1942, when it first saved the life of a patient, penicillin was called the original wonder drug. But aspirin just might steal that title away.

Aspirin is not a scientific term. Rather, it was a brand name patented on March 6, 1899, by the Bayer Co. of Germany. Its active ingredient, salicylate, had been known for centuries. It is found in willow bark, and as long ago as 400 BCE, physicians were giving their patients willow tea to reduce fever.

Scientists continued to develop salicylate from willow bark until 1860, when salicylic acid was synthesized in a laboratory. It was sold as a powder to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation. But salicylic acid caused nausea and acute abdominal pain.

These side effects were eliminated in 1897 when a chemist synthesized acetylsalicylic acid.

It was produced in the laboratories of the Bayer company of Germany. Bayer’s management didn’t want to conduct clinical trials because the substance had failed a preliminary test. The company was more interested in another new compound they had just developed: diacetylmorphine. Bayer marketed it under the brand name heroin, so called because it gave users a heroic feeling.

However, researchers were secretly conducting trials of acetylsalicylic acid in Berlin hospitals. When it proved to reliably reduce inflammation and pain, the company decided to manufacture it under the brand name Aspirin. The name came from the new acetyl group (a) and the genus name of the willow plant (Spyraea).

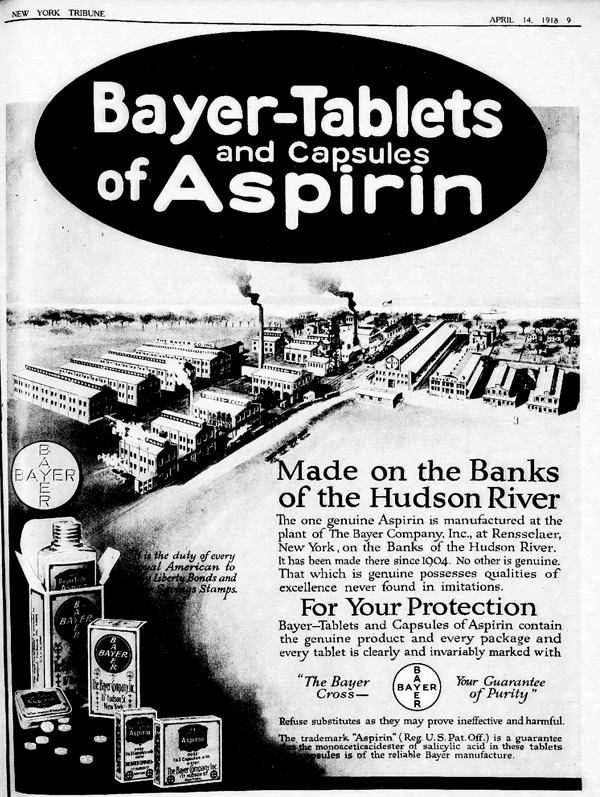

From the beginning, Bayer wanted to distinguish aspirin from patent medicines that promised to relieve pain, so it only sold its aspirin powder to pharmacists and doctors, promoting its use by mailing samples of the powder.

Grateful patients around the world began relying on aspirin for its diverse pains and illnesses. When competitors started to move into the aspirin business, Bayer realized it needed to remind people of the company that developed the compound. To strengthen its ownership of the brand, Bayer began selling aspirin in pill form, on which it stamped its logo. In America, this modest effort at branding drew criticism from the American Medical Association, which disapproved of attempt to commercialize medicine.

Pills were still a novelty to many patients in the 1900s. In Australia, one patient treated for headache was later seen with an aspirin tablet strapped to his head.

When Germany went to war in 1914, it cut off aspirin shipments to its enemies. Great Britain had the facilities to produce aspirin, but it couldn’t obtain phenol, a key ingredient in aspirin — and explosives.

The phenol shortage was also felt in America, where ammunition production was commandeering the phenol supply. The price of phenol shot up, and the Bayer aspirin plant in New York had to reduce production.

Thomas Edison, who needed phenol to make his phonograph records, built a plant that could produce tons of the chemical. In an effort to cripple munition production in still-neutral America, German agents set up a shell corporation to buy all the phenol Edison didn’t use. The Germans provided some to the Bayer Company’s plant in the U.S. The rest was sold at highly inflated prices to American manufacturers who promised not to use it to make explosives. Only after America learned about the arrangement did Edison stop selling to the Germans.

When the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, all of Bayer’s holdings in America were seized and auctioned off. Sterling Products, Inc. purchased Bayer’s brand name, logo, and patents in the U.S., but the company secretly entered a partnership with Bayer in Germany because no one at Sterling knew how to make aspirin.

Not until 1994 did the German Bayer corporation buy back the rights to its old name and trademarks.

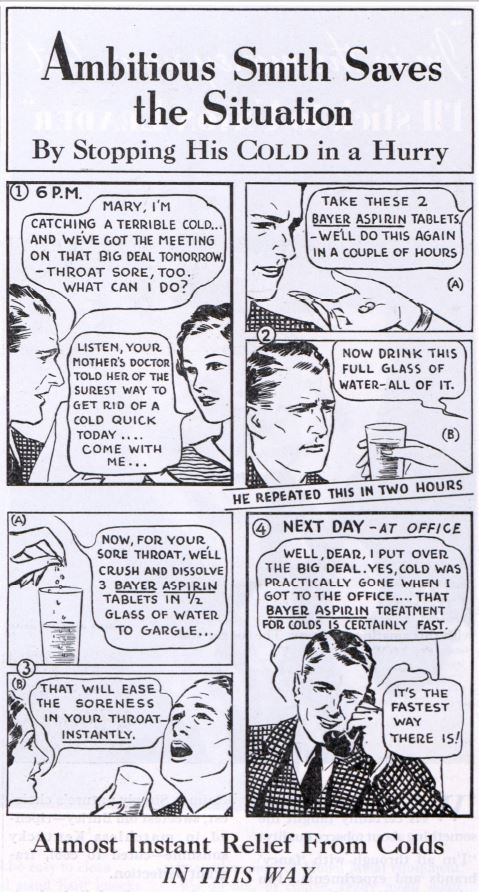

Aspirin became a literal life-saver during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. It relieved pain and reduced fevers, both of which helped some patients endure the infection until recovery could begin. (Though some Americans thought that Germans were wreaking revenge on the U.S. by contaminating aspirin with the flu.)

Between the wars, Bayer promoted aspirin to the corners of the world. No market was too small. The company sent touring trucks, rigged with film projectors and loud speakers to remote villages in distant lands. There, employees presented a film promoting Bayer aspirin. For thousands of people in remote areas, this was the first motion picture they had ever seen.

By the 1930s, Bayer had become part of IG Farben, the chemical firm supporting the Nazi party. (It was Farben that produced the gas used in extermination camps.) Now Bayer was marketing German propaganda as well as aspirin.

Back in America, Sterling Products found itself in an awkward position when the second world war began. Its German partners demanded it continue to produce aspirin and send their share of the profits back to the Third Reich. But if the American government learned of its affiliation with Bayer, and IG Farben, Sterling’s property could be impounded and auctioned.

Which is what soon happened. When the American press learned that Sterling’s overseas business was making money for Hitler, Sterling’s assets were frozen, and the company was forced to fire several executives and break all connections with Germany. Aspirin sales fell sharply.

By the 1950s, aspirin faced competition from other over-the-counter analgesics. The British affiliate of Bayer introduced acetaminophen to the market in 1956. In 1962, ibuprofen became available.

Aspirin sales fell far behind these new compounds. Its reputation suffered more when researchers began reporting harmful side effects of aspirin. Even the buffered, acetyl form of salicylic acid could cause stomach bleeding, and it use was linked to the occurrence of Reyes’ syndrome in young people.

But its reputation was rehabilitated in the 1960s once scientists finally understood how it worked. Aspirin reduces the production of the prostaglandins, which are responsible for the symptoms of pain, swelling, and fever. It also reduces a hormone that enables blood platelets to form clots, which are the cause of strokes and heart attacks. Today, a daily dose of aspirin is prescribed for anyone who’s had blocked blood vessels or is at risk for a stroke.

And aspirin is now being promoted as a cancer-preventive medicine, though it’s not clear how this mechanism works. Researchers continue to study the broadening benefits of this compound.

Featured image: detail from Bayer aspirin advertisement from 1917 (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now