This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Controversial as it may be, the current presidential visit to England nonetheless reflects the longstanding “special relationship” between the two nations. As embodied in particular during times of war, from the First and Second World Wars to the decades of Cold War partnership to the alliance between the Bush and Blair administrations during the 2003 Iraq War, the United States and England have consistently worked in tandem on the world stage for more than a century. If the 2019 version of the relationship seems as fraught and fragile as everything else, that only highlights how solid it has been throughout that prior history.

Yet any contemporary conflicts pale in comparison with the hostile origins of America’s relationship with England. Of course we’re all familiar with the Revolution and the bloody end of America’s colonial status. But in the decades after the Revolution, the relationship between England and the new United States was contested in numerous additional ways, in a series of divisive conflicts that culminated with a June 1812 Congressional declaration of war. The origins of the War of 1812 illustrate not only foundational hostilities between the U.S. and England, but also the fraught nature of national collective memory.

America was involved in several early transatlantic entanglements as a sovereign nation. As part of the conflict with France that came to be known as the Napoleonic Wars (which began in 1803 and lasted more than a decade, coinciding with the War of 1812 in their final years), England cut off all trade to France, and so maintained a blockade on American shipping that the U.S. believed to be illegal. Moreover, that blockade featured the more aggressive tactic of impressment (or “press gang”), with English ships routinely capturing and forcing American merchant sailors into their own navy.

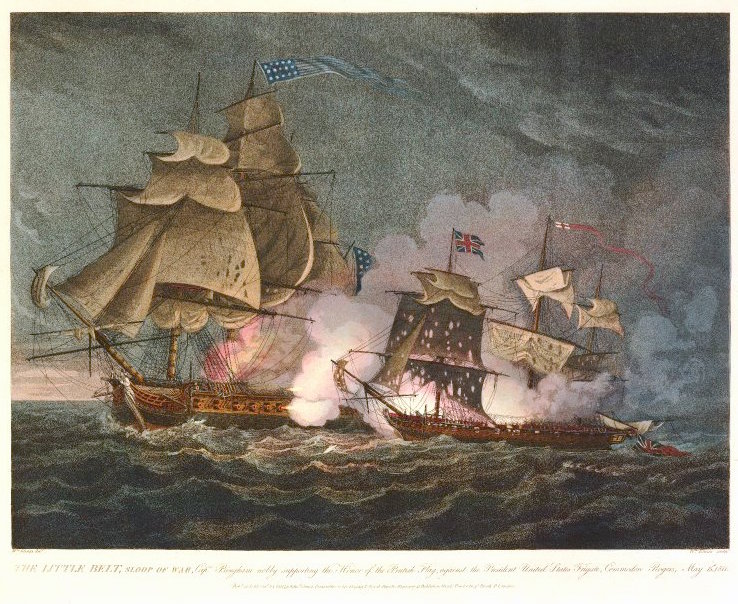

Two specific incidents show how impressment was a form of undeclared war between the two nations. On June 22, 1807 the frigate USS Chesapeake was attacked off the coast of Virginia by the English warship HMS Leopard, which was ostensibly looking for deserters from the Royal Navy; after a short battle the English boarded the U.S. vessel, impressed four of its sailors (who do not seem to have ever been part of the Royal Navy), and hung one for desertion. Four years later, on May 16, 1811, the HMS Little Belt attempted a similar attack on the USS President near North Carolina; this time the American frigate was prepared and fought back more vigorously, leaving 11 English sailors dead and many more injured. That 1811 encounter could be described as the first battle of the War of 1812.

Yet if the Atlantic represented one arena for such Anglo-American hostilities, U.S. westward expansion was another and even more crucial contested space. As early as the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, westward expansion became a central goal for the new United States; the 1803 Louisiana Purchase only accelerated that project. Yet such expansions brought American settlers not into unoccupied territory (despite the controversial argument of David McCullough’s new book on Northwest Ordinance “pioneers”), but rather into direct conflict with existing European settlements and, especially, Native American communities.

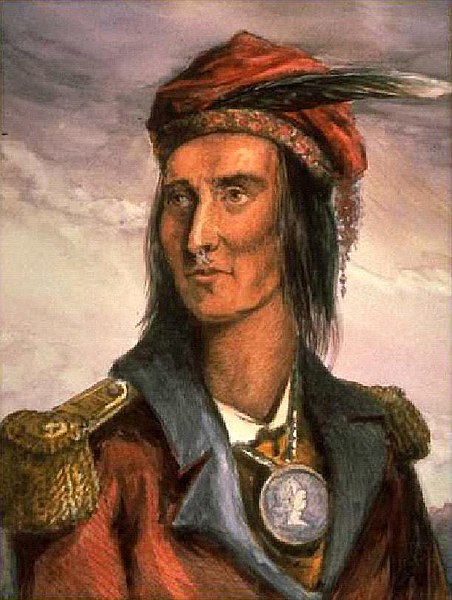

In the decades after the Northwest Ordinance, two Shawnee leaders, Chief Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, led an extensive campaign of military and social resistance to U.S. expansion and settlement. To both protect their own Canadian settlements and frustrate U.S. expansion, the English consistently supported those native efforts, providing arms and other supplies to bolster the campaign. While native resistance and raids took place over many years, they became more frequent and potent in the early 19th century, with 1810 and 1811 comprising the most active years. These hostilities culminated in the November 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, which could likewise be defined as an early conflict in the War of 1812.

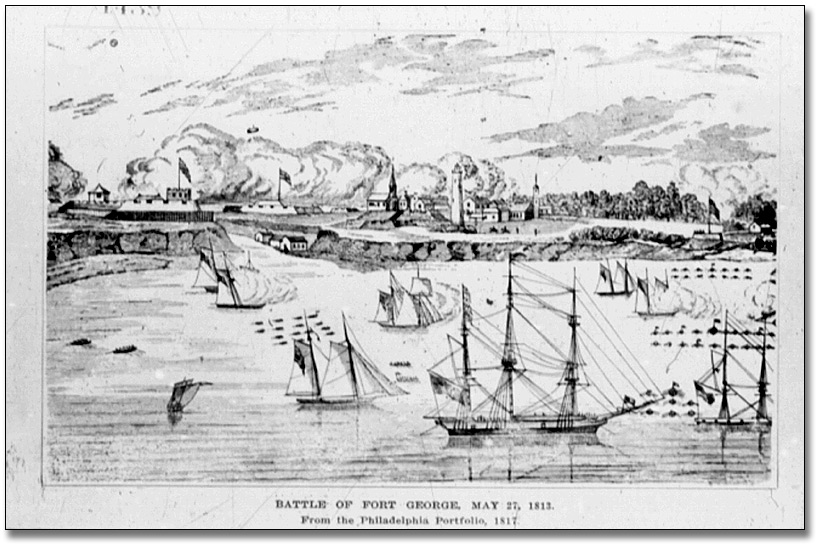

American historians have generally argued that it was in response to English aggressions in both these arenas — impressment on the seas and aiding native military resistance in the Northwest — that Congressional “War Hawks” pressured President James Madison to declare war in June 1812. Yet English histories of the conflict present a far different picture, as illustrated by the historical markers at Ontario’s Fort George, site of multiple War of 1812 battles that culminated in the May 1813 U.S. destruction of the fort and much of a neighboring town. The version of events highlighted at Fort George depict American expansion and aggression as the war’s driving forces, and the era’s stories of English impressment and native alliances as propaganda constructed in order to justify military actions like the invasion of Canada.

For the English, that invasion has become a central facet of their 1812 history. For Americans, on the other hand, the war is remembered through two interconnected images: English troops burning the White House and much of Washington, D.C. in August 1814; and the September 1814 successful defense of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry that inspired Francis Scott Key to compose the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Thanks to such images, the War of 1812 had often been considered in the U.S. as the “Second War of American Independence,” a link to the Revolution that further emphasized the ongoing Anglo-American hostilities out of which it originated.

As always with wars, the truths of history are uncertain and ambiguous, and likely include all these and other factors as well. Yet in any case, these show that hostilities between England and America did not end with the Revolution and the creation of the United States. They also became a defining element of the United States’ identity throughout the Early Republic period. Remembering them helps us understand that era, America’s origins, and perhaps the state of our “special relationship” with England in 2019.

Featured image: The Burning of the White House, 1814 by Tom Freeman (White House Historical Association)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now