Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott: Celebrating Labor Day

Bill Newcott shares his favorite clips of the working man and woman, from Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times Meryl Streep in Silkwood to Michael Peña in Cesar Chavez. Let us know your favorite!

See all Movies for the Rest of Us.

Featured image: Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

News of the Week: Back to School, Twitter Insults, and Here’s the Right Way to Pronounce ‘Gyro’

Sorry Kids!

Where I live, school doesn’t start until after Labor Day, and every year I’m always surprised to find out that they start school in August in many parts of the country. August! Some places started school two weeks ago! It’s just not right to make kids carry backpacks and worry about long division in the dog days of summer. There should be a logical point where summer ends and school begins, a definite line, and when I was growing up, that line was always Labor Day.

It reminds me of this classic Staples commercial. It’s a shame they don’t run it anymore. It perfectly captures what it feels like for both kids and parents when the new school year starts (though shopping for new school supplies was always one of my favorite things to do).

The kids in the commercial probably have their own kids now.

All the News That’s Fit to Quit

People are often called nasty names on Twitter. Most of those words are too extreme to repeat in America’s oldest magazine. Being called a “bedbug” is way, way down on the list of unacceptable names you can call a person on social media. There must be, what, 70,000 to 80,000 insults ahead of it?

Not according to controversial New York Times opinion columnist Bret Stephens. He was called a “bedbug” by a professor at George Washington University (the Times had a bedbug infestation last week and the professor compared Stephens and his writing to the annoying insect). Stephens promptly freaked out, which is odd, because the professor didn’t even use Stephens’s Twitter handle in his tweet, and the tweet originally only got a handful of likes and no retweets (God, I can’t stand social media). Stephens either got a heads-up from someone who saw it, or he’s the type of guy who searches Twitter or Google to see if anyone is talking about him.

That practice is rather innocuous, but what Stephens did next wasn’t. He could have just written a snarky tweet back or forgotten about it, but he went ahead and sent an email to the professor telling him to come to his home and “call me a bedbug to my face,” CC’ing GWU’s provost and the Director of the School of Media and Public Affairs. That’s right, Stephens snitched on the professor.

In an appearance on MSNBC that just made things worse, Stephens said he wasn’t trying to get anyone in trouble when he sent a copy of the email to the professor’s bosses. Alrighty then.

The professor, Dave Karpf, wrote an essay for Esquire about the controversy and how he felt when it went viral.

I will say that I agree with Stephens on one thing: Everybody should quit Twitter.

Farmer’s Almanac Predicts Bad Winter

When I read a headline like this, my first thought is, “Oh no, it’s going to be sunny and humid?” Because that would be my definition of a “bad” winter. Of course, that’s not what the Farmer’s Almanac means. They mean it’s going to be colder and snowier than usual.

Example #2517 Why We Need the Oxford Comma

Newt Gingrich, a three-star Air Force general and former publicist for Michael Jackson and Prince want to create a $2 billion sweepstakes to see who can establish and run the first lunar base https://t.co/Pp40LUqZ7x

— POLITICO (@politico) August 19, 2019

RIP David Koch, Jessi Combs, Charles Santore, and Neal Casal

David Koch was the head of Koch Industries, the multi-billion-dollar global company that deals in everything from finance and energy to natural gas and ranching. Koch also gave millions to cancer research, education, and the arts, including PBS, as well as to conservative political organizations. He died last week at the age of 79.

Jessi Combs was a professional speed racer known as “the fastest woman on four wheels.” She was also a fill-in co-host of the Discovery Channel show Mythbusters. She died this week attempting to break a speed record in Oregon’s Alvord Desert. She was 36.

Charles Santore was an acclaimed artist and illustrator known for his work on children’s books, including a well-received 1991 edition of The Wizard of Oz. Earlier in his career he did illustrations for advertisements and TV Guide, including a great cover of Peter Falk as Columbo. He died earlier this month at the age of 84.

Neal Casal was an influential guitarist who not only released many solo albums, but also worked with artists such as Willie Nelson, Ryan Adams, Shooter Jennings, and Lucinda Williams. He died last week at the age of 50.

Quote of the Week

Little bit of a conflict of interest that Lucy is both Charlie Brown's therapist and his biggest bully.

— Nathan Rabin (@nathanrabin) August 26, 2019

This Week in History

The Fugitive Finale Airs (August 29, 1967)

The Harrison Ford big-screen adaption of the ’60s David Janssen series is often described as a “great” movie. It’s … okay. There’s nothing really wrong with it, but when you’ve seen the original series and know that Dr. Richard Kimble was on the run for four seasons, it’s a whole different thing. The ending of the movie doesn’t pack the satisfying punch of the two-part series finale of the TV show, which everyone tuned in to watch.

Author Mary Shelley Born (August 30, 1797)

It amazes me that Shelley was only 20 years old when her classic monster novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published. She started writing it when she was 18.

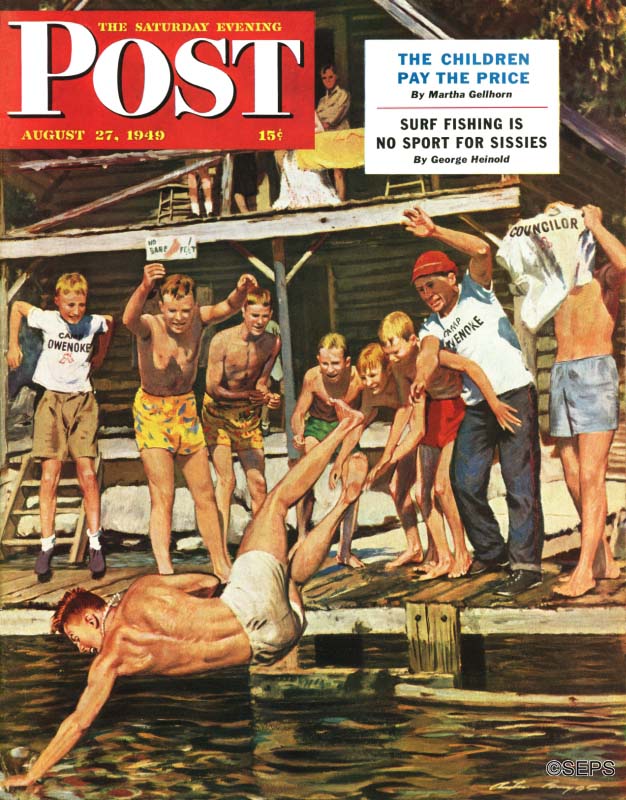

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Wet Camp Counselor (August 27, 1949)

It was the end of the summer. The kids had put up with too many orders, too much bullying, too much yelling from the head counselor. That’s when they decided to push him into the water. And life at Camp Crystal Lake was never the same after that …

Sunday Is National Gyro Day

It’s that time of the year when we all need to remember how to pronounce gyro, and I used the word year to give you a big clue. The correct way to say it is “YEAR-o,” and not “JAI-ro” or “GEAR-o.”

Here’s a recipe for Gyro Meat with Tzatziki Sauce from Alton Brown, and here’s one for a Homemade Greek Chicken Gyro from The Mediterranean Dish. I can pronounce Mediterranean, but I always forget how to spell it.

And while we’re talking about how to say certain foods, let me just add that daiquiri is pronounced “DAK-ari,” açaí is pronounced “a-sigh-ee,” and bruschetta is pronounced “bru-SKET-a.” You’re welcome. And if you don’t agree with me on how to say those words, I invite you to come here and say them to my face.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Labor Day (September 2)

I miss the Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day Telethon.

Newspaper Carrier Day (September 4)

Not to be confused with International Newspaper Carrier Day, which is in October, this day celebrates Barney Flaherty, the first paperboy, hired by The New York Sun in 1833.

I hope you subscribe to a print newspaper, get it delivered to you, and tip well. In another 10 or 20 years it might be one of those occupations that goes the way of switchboard operators and bowling alley pinsetters.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com.

60-Year Bath

That summer, the gender-neutral change room changed everything. The university, accused of being behind the times, finally put one in. For Professor Mulligan, it was amnesty enough to come around on purchasing a campus aquatics membership. It was a way to avoid the posturing, the testosterone, the groupthink of “bros” in the men’s room. Not to mention the mindless, aggressive music spewing from Bluetooth speakers in there these days. Also important: private stalls. You weren’t out in the open. You weren’t exposed.

The professor, a portly fellow, portlier in fact with each passing semester, didn’t undress in front of people. There was a vulnerability, a certain shame in being on display. That afternoon, in his stall, Mulligan loosened his tie, unclipped his suspenders, and unbuttoned his sweat-stained dress shirt, unleashing mayhem. To the tune of two bulging rolls of belly fat and a pair of droopy breasts, all of it topped with matted gray chest hair. This wasn’t who Mulligan was supposed to be — he felt out of place in his own body. Did he have regrets? Who didn’t?

“Professors of psychology don’t have any fewer demons running around inside than anyone else,” Mulligan was known to lecture. “We’re able to identify them, put names to them, that’s all.”

And he didn’t necessarily mean clinical names. Mulligan gave his demons people names. Harley, for example, was the part of Mulligan that ate too much, the part fixated on consumption, on overconsumption. The addict. As a child, it was food. As a teen, as an adult: cigarettes, alcohol, then opioids. Now, as a senior — after nicotine patches, Alcoholics Anonymous, and three stints in drug rehab — Harley was back to food. Harley, the gluttonous slob, was effective, though. Damage control was a tough racket, but Harley was a world-class trauma assassin, burying fear and insecurity beneath thick greasy mounds of fast food and potato chips. It sounded silly, but personifying internal psychological processes, caricaturizing them, somehow made it feel like there was a team within, somehow made Mulligan feel less alone. In a weird way, it helped him understand who he was.

Mulligan pulled on a black T-shirt because going out onto the pool deck topless was not an option. Imagine if one of his Gender and Development students saw him in such a state, half-naked, defenseless like that.

Swimmers in goggles and latex caps filled all eight lanes of the Olympic-sized pool. Their strokes varied, but all cut through the water expertly. One end to the other and back again. With purpose.

Mulligan turned to the therapeutic hot pool. It was empty. The sign there suggested consulting your doctor before entering. It warned that more than 10-15 minutes in the hot pool was potentially detrimental to your health, that prolonged “enjoyment” could cause disorientation.

The lifeguard, a muscular kid in a mesh tank top, watched Mulligan in a way that made Mulligan feel like he was doing something wrong. Was it the T-shirt? Were T-shirts not allowed? Mulligan raised his hand and the kid nodded at him like the two of them had known each other forever.

The first step into the scalding water immediately reminded Mulligan of the baths his mother ran for him as a young boy, how unbearably hot she always made them, how long it took for him to ease his way in, how impatient she was with the whole ordeal. This is a bath, she’d say. Baths are hot. This is how you get clean.

Mulligan took another step — down to knee depth — and stopped again. He stared out the window at a tree, a thin stick of a thing by the walkway to the parking lot. Scraggly branches and wilting leaves drooped in the sweltering heat. The twig-like tip flopped to the side — like it was giving up.

One more step and the water was all the way up Mulligan’s thighs, perilously close to his scrotum. He stood there for what seemed like hours, and he would have stood there a few hours more had a swimmer not gotten out of the main pool, peeled off his goggles and cap, and walked over to the hot pool behind Mulligan. Feeling the pressure to get out of the guy’s way, Mulligan took the final step — waist level — and his hands instinctively moved to his submerged crotch. It was futile protection — screen door on a submarine came to mind — but Mulligan’s hands stayed there. It was psychological.

The swimmer stepped all the way in and sat right down, waterline at his nipples. Just like that. Like it was nothing. Mulligan, XXL shirt stretched tight across his belly, took a deep breath — then a few more — working up the nerve to sit.

Then he sat. Nerve endings across his body — a hundred thousand of them — under siege from the intense heat, sent a hundred thousand distress signals to whatever part of his central nervous system was in charge of pain management. There was a rush of blood to his head, a pleasant tightening around his brain — reminiscent of a warm opiate buzz. Then a sort of weightlessness, a drifting of consciousness, an altered state: Mulligan overload. He turned to the sign on the wall: No person having a communicable disease or open sores shall enter the pool. Suddenly drained, Mulligan’s eyes rolled back in his head.

Communicable disease. Mulligan’s mother had died of pneumonia. All that time she spent in the hospital. Weeks. But it felt longer than that. Like years. He stayed with her, all night, every night, at her bedside. Those nights were long. Time had a torturous way of stretching out. The sound of his mother struggling for breath, the crackling of her windpipe, it was unbearable. All Mulligan could do was sit there. Watch his mother wither, sink into the bed. And through all of it, he never worked up the nerve to talk to her, to really talk to her, to explain to her who he really was. Morbid maybe, but his secret would have been safe; it would have died with her. Instead, she died and there was an entire part of her only son she never knew.

Mulligan opened his eyes.

The water in the pool was still very hot, but he’d at least gotten over the shock. He’d acclimatized. He’d get out soon — more than 10 to 15 minutes was potentially detrimental — but for now he enjoyed it.

Another lifeguard, a young woman in a canvas fishing hat, whistle in mouth, flutter board under arm, patrolled the deck. She paced with self-assuredness. Comfortable in her own body. Reminded Mulligan of Pauline, a student in Gender and Development. He admired Pauline. She was sure of herself. She knew who she was.

Mulligan was in the hot pool alone. The guy, the swimmer who’d peeled off his goggles and cap, gotten into the hot pool with Mulligan, was gone. The waterline was at the guy’s nipples. The waterline was at Mulligan’s nipples. And everything underwater moved on its own. His shirt rippled with the current of filtered water shooting out of jets. His liver-spotted arms floated and bobbed, a dissociation of the limbs, a disconnect between movement and conscious thought. Mulligan was an expert on dissociation: authored a textbook, had personal experience, invented a character to represent the part of him responsible for disconnecting from thoughts and feelings, the part that spearheaded efforts to check out mentally when Mulligan was triggered. This was Spencer, the scrawny trembling twerp who always had an escape plan, who always had the white flag cocked and ready. Spencer, second in command in Trauma Suppression, dealt with what Harley couldn’t bury beneath food. Mulligan was open about his internal cast of characters — his team — in class.

“You’re allowed to make a little light,” he was known to lecture. “Take this stuff too seriously and you’ll cripple yourself under the weight of it.”

What Mulligan wished he’d have been open about was his identity. He wished he’d never kept it a secret in the first place. Pauline, the young woman in Gender and Development, wasn’t afraid to open up about her identity. She came to see Mulligan during his office hours, went right into it, told him everything. Pauline had been born Paul. But even as a child — for as long as she could remember — she knew that wasn’t who she was. She knew she was a girl, a young woman. And she told people about it. Without hesitation. It would have been safe for Mulligan to reciprocate, to open up to Pauline about his own identity, but he couldn’t work up the nerve. Instead she left Mulligan’s office and Mulligan envied her from a distance.

Soaking in the hot water made Mulligan feel healthy: blood flowing, pores sweating out toxins. He pictured little particles — nicotine remnants, lingering alcohol and opioid debris — exiting his body, his inner custodian, Dana, the unappreciated diligent worker, toiling away, deciding what stayed and what went. This was a bath. This was how you got clean. And 10 to 15 minutes wasn’t going to do it: Mulligan had 10, 15, 30, 60 years of damage to undo. Maybe he’d just stay. Maybe he’d soak for as long as it took. He’d already been here a while. Look how dark it was getting. Look how chilly: students pinching coats shut, hurrying to the parking lot. Look at that tree by the walkway, its branches stripped clean of leaves. Look how it stood firm in the whipping wind. Mulligan sank down, shoulders in the water, happy to be in out of the cold, and breathed easy.

Mulligan had breathed easy when he finished AA. He wasn’t a model member. He went through with it, said all the right things, but never took any of it seriously. Everything about it: the patronizing tone, the Jesus stuff, the sheep who ate up the Jesus stuff, the general embarrassment of being there, being one of those people. Mulligan thought of himself as the rogue member, the outsider, the one who was above it, who didn’t need it. He got sober, though — his inability to identify with group members who’d lost jobs and gone to jail minimized his own problem. And showing up, going through the motions, participating when prodded was somehow enough.

The three boys across from Mulligan in the hot pool were drinking. They sipped from cans of All Nighter, an energy drink the university had banned from campus ages ago. Mulligan looked at the lifeguard, a scrawny kid in a ball cap, to see if these boys and their drinks were going to get the boot. The lifeguard, meek and nervous-looking, watched the hot pool from afar. He saw what was going on. Didn’t have the stomach to do anything about it. Like Spencer, Mulligan’s inner escape artist, his coward extraordinaire. The boys drank their sugar-loaded drinks, their testosterone fuel, and raged about the difficulty of their commerce courses: taxation this, inventory accounting that.

Making a “searching and fearless moral inventory” was Step Four. They had circle time in AA. Talked about their feelings. Mulligan made up a bunch of stuff about having a family, being divorced, drinking because he lost custody of the kids. What else was he going to do? Spill his secret? Expose what Harley and Spencer had spent a lifetime supressing and avoiding? To that room of real-life Harleys and Spencers? Because those were the people who were going to understand what it was like to live a lie? Okay, maybe they were exactly the people to understand. The point was: the AA gang — generously tattooed, excessively pierced — wasn’t the gang Mulligan wanted on his side, the first to know that he felt like an alien in his own body, that this god they were all so fond of screwed up with Mulligan at birth, that Mulligan, crippled under the weight of everything, never worked up the courage to live his life the way he was supposed to. Maybe Mulligan should have told them though. Times were changing. Kids nowadays knew who they were and they were coming right out with it, addressing gender dysphoria like it was nothing. Like goddamned heroes.

This was the best Mulligan felt in a long time. Just needed a good long soak to loosen him up. His shirt seemed to be loosening up. This was what it felt like to be in shape: your shirt wasn’t stretched tight, you had some breathing room. It was dark outside and Mulligan could make out his reflection in the window. And — weird — he didn’t hate what he saw. He almost looked young. Almost looked clean.

Every so often, new people appeared. And, just like that, they were gone. Some would push the button to start the jets. The jet at Mulligan’s lower back numbed the base of his spine.

Lifeguards came and went. Alternating watches. Rotating shifts. Periodically sampling the water, testing chlorine levels. It was a constant fight with the pH, a delicate balance. They all knew him by name: Professor Mulligan, The Soaking Man.

Nights would be the hardest. When distractions disappeared. When you were alone with your thoughts. When time had a torturous way of stretching out.

Then there was the winter. It would come with a vengeance. Blizzards, squalls — storms of people’s lifetimes. There would be a tree outside, a thick beast of a thing by the walkway to the parking lot. Snow would pile on its sturdy branches but they’d hold the weight. Those branches were in it together: units with roles, cogs in the machine, contributing to the whole. A team. Forging an identity.

Mulligan sank down, water at his chin, a vantage point that made it look like the water level had risen, like the tide had changed. His shirt rippled with the underwater current. Mesmerizing how it moved on its own. Reminded Mulligan of how he often felt: passive, affected, lacking any say in the matter. It certainly summed up suffering through puberty: having no control over the way his body transformed itself. It was during puberty that his mother stopped letting him into the women’s change room at the public pool. You’re too old for that, she said. They’ll think you’re a pervert. So then it was the men’s room. Where grown men undressed in the open. Where everything hung out. The overwhelming wrongness of that.

Mulligan fixed on his rippling shirt, letting the current happen to it. Felt nice that the shirt was loose on him, that he was swimming in it. Felt nice to be young, to be healthy. Felt invigorating. And he wasn’t going to take it for granted this time.

Soon spring would come. That tree would bud again. And — even if just a little, even if imperceptibly — it would be stronger than it was before. After enough time it would grow taller than the building. Out of its shadow. Cast a shadow of its own. Because showing up, going through the motions, was somehow enough.

Featured image: Shutterstock

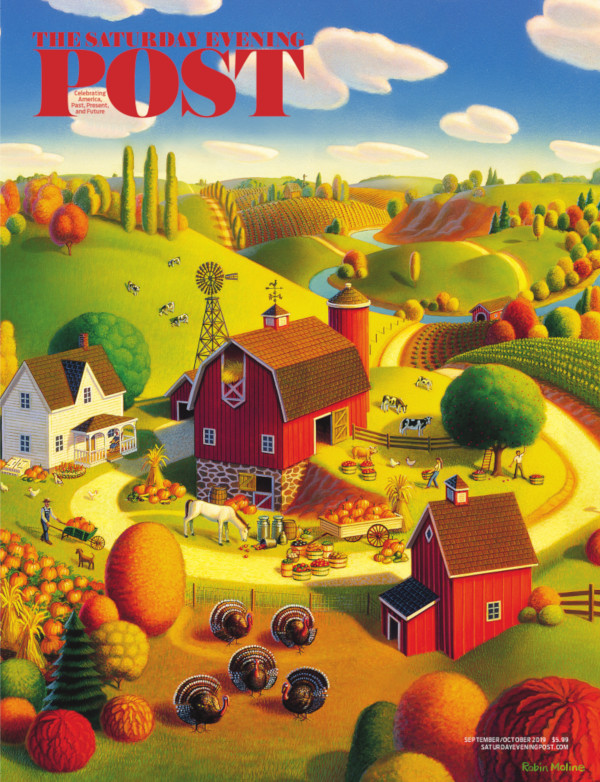

Preview Our September/October 2019 Issue

In the most recent issue of The Saturday Evening Post read about the importance of teaching history to our children and grandchildren, the untold story of Annie Oakley’s fierce rival, Hunter the rescue dog, plus books, recipes, health tips, everyday heroes, and more.

Featured image: Robin Moline / SEPS.

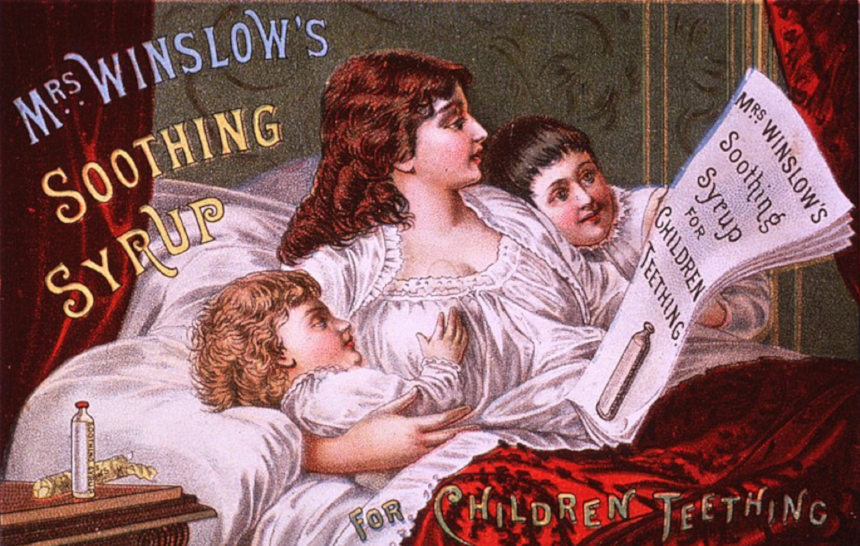

America’s First Opioid Epidemic

For thousands of years, doctors relied on opiates to relieve suffering. It was one of the few compounds that could offer immediate, guaranteed release from pain. And opiates have always played a role in America’s story.

The first opiates probably came to America in 1620, arriving in the trunk of the doctor who had sailed on the Mayflower.

Opium was still in use during the Colonial Era. Thomas Jefferson, for example, relied on opiates to ease his suffering in his final years. (Ever far-sighted, he planted opium poppies on his property. They continued growing at Monticello until the 1990s, when the Drug Enforcement Agency pulled them up.)

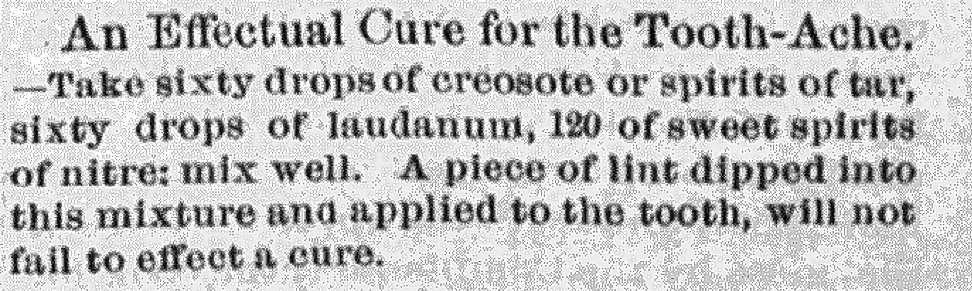

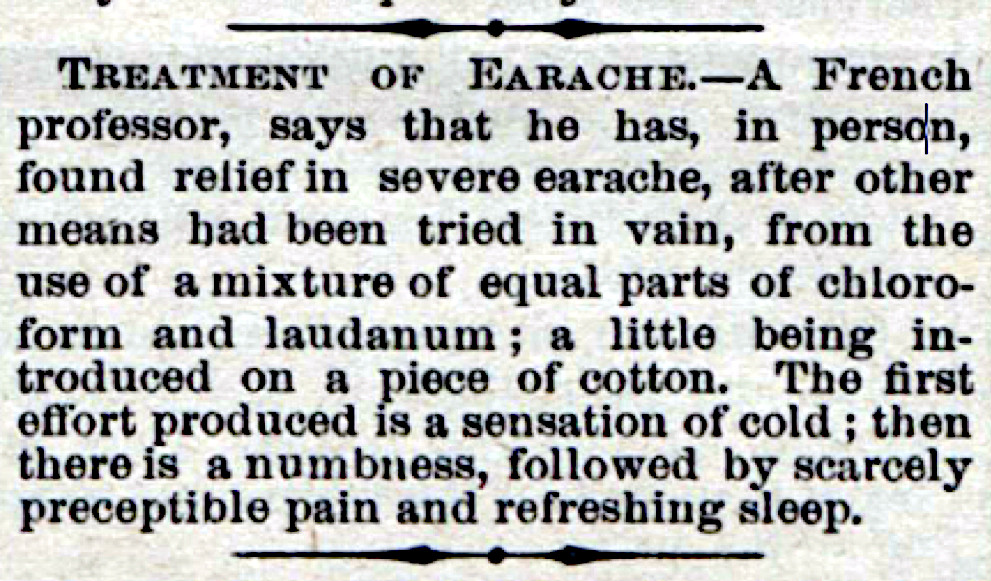

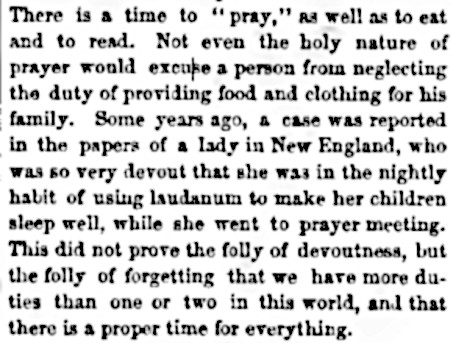

In the 19th century, the most common opiate was laudanum, a mixture of opium and wine. It was widely available (without a prescription, of course) and it cost less than alcohol.

In those early times, there was no stigma attached to its use, or abuse. The Post, in 1833 recommended it for treating bee stings or persistent coughs (combine molasses, vinegar, wine mixed with with 40 drops of laudanum).

It could also be used on children who were teething. But adults also found laudanum was an easy way to get their infants and older children to sleep, especially since the side effects were little known at the time. In 1858, The Post reported that one lady in New England solved her baby-sitter problem by putting her children into a deep sleep with laudanum so she could attend nightly prayer meetings.

In an 1864 Post article on factory towns, the author described the desperate state of child day care. Working women might leave their offspring with elderly caretakers who dosed the children with laudanum so they’d remain quiet and manageable.

The majority of opiate addicts in the late 1800s were middle- to upper-class women. They turned to laudanum because, in the Victorian era, they had limited access to alcohol. No respectable woman could buy liquor or enter a saloon.

Laudanum was considered a source of inspiration for artists, composers, and, especially poets. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning were all familiar with, if not addicted to, laudanum.

In the post-Civil-War years, opiate use rose sharply. Many wounded veterans, who’d been given the painkiller in military hospitals, became life-long addicts.

But there was even greater use among civilians, some of whom became addicted when trying to escape the pain of a chronic illness, bankruptcy, unemployment, or the death of a loved one. This heavy use of laudanum caused the death of thousands. And deliberate overdosing became the most common means of suicide.

Later in the century, the dangers of the drug were becoming more obvious, as reflected in the Post’s coverage. An April 6, 1872, article stated, “A careful inquiry among druggists reveals the fact that there are in New York city about 5,000 confirmed users” (out of a population of less than 100,000).

In a later article, the editors wrote:

The use of laudanum as a drink is fast increasing. In most cases it is used with alcohol to lessen the irritating effect of this drug, or the result of excessive alcohol, as a sedative, or as a stimulant. In England a favorite preparation used after drinking is called a “Pick me up.” In some large cities, druggists give compounds of laudanum and ginger under fanciful names, and these are resorted to always after, in place of alcohol. This accounts for the enormous sales of opium, of which not over one fifth is used in medicine.

Laudanum abuse wasn’t just a big-city problem, either. An 1894 editorial reported, “Anyone who doubts the continued prevalence of the opium-taking habit would soon be convinced if he glanced over the chemists’ preparations for a rural market-day.” Country folk, it continued, took laudanum not to alleviate pain, but to bring “artificial excitement” into their sedate, rural lives.

Doctors had been alerted to the dangers of addiction starting in the 1870s. But the warnings had little chance of reaching doctors living in the country. Even among physicians who knew better, it was difficult not to prescribe laudanum for their patients in agony; there simply was nothing else. And opiates continued to be the prescription of choice for patients.

Even as America awoke to the dangers of opiates, little was done to discourage its use. Between 1898 and 1902, the opium and morphine business more than doubled. The rate of addiction was nearly three times higher than in the mid-1990s.

A reforming spirit emerged among Americans in the 1900s. One of the chief areas of concern was the unhealthiness of food and drugs, many of which included opiates.

Another factor was an outcome of the recent Spanish-American war. The U.S. had taken over the administration of the Philippines, which had a thriving opium trade. President Theodore Roosevelt requested an international opium commission to exert some control over opiate traffic. But he realized the U.S. couldn’t control drug traffic in the world if it couldn’t control it at home.

In 1909, Congress finally criminalized the importation, possession, or smoking of opium. Later, the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Tax Act required all importers, manufacturers, or dispensers of any opium product to register with the government.

The opioid epidemics of then and now are similar in many ways, but there is one great difference. Doctors and opioid addicts in the 1800s could plead ignorance of the dangers within these substances. We don’t have that excuse today.

Featured image: “The countess, having taken a dose of laudanum nears death” Engraving by Louis Gérard Scotin after William Hogarth, 1745. (Wellcome Collection gallery, CC-BY-4.0)

In a Word: Cracking Open the Walnut

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

Trees in the genus Juglans have been cultivated, both for their wood and their nuts, in continental Europe for so long that their historical distribution cannot be accurately tracked. It took some time, though, for them to make it to Great Britain. When the English finally got their hands on these nuts, they called them, in Old English, wealhhnutu — that’s wealh “foreigner” + hnutu “nut” — to differentiate them from their native hazelnuts. Over time the name was simplified to walnut.

Walnuts are literally “foreign nuts.”

So the wal- in walnut has nothing to do with walls, nor is it the same as the wal- in walrus. (Walrus is of Scandinavian origin and literally means “whale horse.”) But that Old English root is shared with a couple of other words you might not expect.

When the Anglo-Saxons invaded what we now call Great Britain, wealh (“foreigner”) and its adjective form wælisc (“foreign”) are what they called the island’s native Celts — which, yes, is ironic considering they were the invading force. The words stuck, and over time, those labels became Wales and Welsh.

The Welsh don’t call themselves foreigners, of course. In the Welsh language, the country is Cymru and the people are Cymry. Both words are pronounced “KUM-ri” and derive from an older word meaning “compatriot.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Accidental Beekeeper

As the mild San Francisco morning sun fills the back of my station wagon, I wrestle with two stacked boxes buzzing with a low hum. I can’t afford to slip or drop them: Inside is a colony of honeybees.

Until recently I was a helpless city slicker, prone to startling and swatting at anything buzzy. I couldn’t even tell a bright yellowjacket from a striped honeybee. Yet here I am, veiled and covered up, hugging two supers — wooden boxes making up a hive — full of bees, wax, and honey. I’m now one of many amateur beekeepers fostering the winged creatures in urban and suburban communities around the country.

Numbers vary widely from study to study, some citing upwards of 120,000 Americans looking after honeybees on rooftops and in backyards. There may be no way to compute an accurate number, according to Dr. Dewey M. Caron, a University of Delaware entomologist, but nonprofessional beekeepers are thought to own up to 10 percent of all bee colonies. “Now, that may not sound significant,” he says, “but backyard beekeepers are some of the most active individuals in influencing legislators and policymakers. They serve a crucial part in maintaining bee populations.”

I had no eureka moment or activist manifesto. Over the years I read about the bee’s crucial role in pollination — and therefore human survival — and slowly began daydreaming about lending them a spot to live: my idea of low-commitment community service, perhaps. I read a few beekeeper blog posts, fell into a YouTube rabbit hole, and took a weekend class. Once I was reasonably confident, I answered a call to adopt a hive.

My bees were rescued in Silicon Valley, 50 miles south of where I live, the last block before the foggy city gives way to the Pacific Ocean. Having stealthily nested behind a boarded-up window in an abandoned house in Palo Alto, this colony was about to become homeless when developers decided to fix up the building. (If ever there was a place for a joke about the Bay Area’s ever-worsening housing shortage, this would be the punchline.) Just in the nick of time, three volunteers went in to take apart the stalactite-like mass into sheets of waxy comb, full of honey, bees, and soon-to-hatch babies, placing them into a Langstroth hive, a commonly used box to keep bees.

“My beehives are like pets,” she says as she helps me install the hive in my yard. “They’re a part of my family.”

My friend Cheryl Chang was one of the rescuers. Though master beekeepers spend their lifetime honing their skills, picking up the basics is less intimidating than most people might think. Cheryl has gone from a complete novice to being capable of capturing wayward swarms by dedicating a few hours a week over two short years to this hobby.

In Mountain View, better known for tech giants like Google than bucolic pursuits, the philanthropic service professional keeps a tidy garden of avocados and pear trees, lemon verbena and pineapple guava bushes. Tucked in the corner by the fence, her two hives whir with activity year-round, producing gallons of honey more fragrant than anything I’ve bought from a store. As a matter of fact, some studies claim bees, who forage for miles each day, are healthier and plumper in cities and suburbs, where they have access to diverse ecosystems offering a wider array of diet than monocultural farmland where there are only, say, bitter almond blossoms. In turn this can lead to higher honey yields.

But Cheryl’s not in it for the sweet nectar.

“My beehives are like pets,” she says as she helps me install the hive in my yard. “They’re part of my family.”

Quite a statement for creatures you can’t teach to roll over on command. And forget stroking them or snuggling up with them on the couch. I couldn’t have understood her comment until now.

As soon as we remove the netting that kept the hive sealed for the car ride, dozens of bees spill out and hover around the hive’s entrance, trying to take in their new environs. A few bees form a line on the landing strip of the entrance and start what could only be described as twerking.

“They’re fanning out the hive’s scent,” Cheryl tells me. “So the other bees from the colony can find their way back.”

Right away I’m smitten. Then everything clicks in my head. I’m less a landlord or an amused dilettante than a guardian. The responsibility for these lives suddenly weighs down on me. To stave off an imminent anxiety attack, I concentrate on what I’ve learned about bees.

A few months back, I sat with about 30 people, mostly under 35, around a long table in a warehouse doubling as the classroom for San Francisco Honey & Pollen. We were attending an introductory beekeeping class, and for most of us, the translucent comb being passed around was the first we’d touched of this marvelously geometric structure that bees build with their secretions.

By trade, John McDonald retrofits homes for earthquakes, but he’s also what the honey industry calls a sideliner, a part-time enthusiast who derives some income from keeping bees. He began keeping a few hives in the back of his lumber workshop as a hobby, and by 2006 he was selling honey and sharing the knowhow he’d picked up. Now he teaches upwards of 1,200 students a year.

The surging popularity arrives at a critical juncture, as honeybees today have it harder than ever. Coming into public prominence in 2006, the massive disappearance of bees known as Colony Collapse Disorder kills up to half of all hives in some areas, with some beekeepers reporting 90 percent of their stock perishing. But despite the urgency — and the subsequent popularity of amateur beekeeping — only a select few actually pursue the hobby.

“I’d say only about 1 percent of the attendees go on to start beekeeping,” John said.

Right away I’m smitten. Then everything clicks in my head. I’m less a landlord or an amused dilettante than a guardian.

Who were these curious onlookers spending their hard-earned day off in beekeeping suits? A couple next to me revealed that they were on a second date. A dyed-in-the-wool Berkeley baby boomer declared, “We all should help bees save the world.” Another woman confided that she was really just there for the honey tasting. Many had come, from the sight of it, to snap selfies in white overalls and black veils.

For the next few hours we got a crash course, part biology, part veterinary medicine, and part petting zoo. A colony, we learned, is led by one queen who takes to the sky only for a few days in her first spring in order to collect sperm, and spends the rest of her years continuously laying eggs. Some of these eggs become drones, or male bees whose sole purpose is to mate with a queen from a different hive (and, oh cruel nature, immediately die). But most become female worker bees who devote their lives to labor, from feeding hatchlings to pampering the queen. Their tasks evolve as they mature, not unlike human workers who get promoted, and they learn to guard the hive from intruders before they take to the skies to forage for nectar, pollen, and water. They will work themselves to death in as little as six weeks, perpetually replaced by the next generations that they raised.

As with any other animals, it’s tempting to anthropomorphize these critters. Some hives are genial, others downright mean — as broad as the spectrum of human personalities. Among the dozen hives in the yard, we were steered away from one containing aggressive members while McDonald, in only shorts and a veil, cracked open others that were so docile that his hands were left ungloved. The queen’s genetics and pheromones determine her colony’s personality, and it’s not unheard of for a seasoned beekeeper to commit regicide and set up a new royal if the subjects are deemed too violent.

Callous as it may sound, few things shatter the myth of benevolent Mother Nature like witnessing bees’ Machiavellian tendencies. In the yard behind the warehouse, I watched in horror as one bee struggled to cling on to another that was hauling it out of the hive and dropping it on the ground. Sick or dying bees, we learned, get cleared for the common good.

Lucky for me, the hive that comes to my yard turns out to be very mellow. I fret about everything — whether to keep feeding them sugar syrup to ease their transition, whether they’re hovering around the hive too much, and whether I should actively fight ant intruders with cinnamon — prompting my friends to say that I sound just like the nervous first-time moms that they used to be. Stop worrying you might kill them, they advised me, and just enjoy.

In the weeks following their arrival, they learn to soar high above the house to head toward the Golden Gate Park, a veritable buffet of prime forage. I worry less and less about these gentle newcomers attacking neighbors: A relief because, although cities from New York to Los Angeles have been changing laws to allow beekeeping, many urban dwellers understandably fear any creatures equipped with stingers. By law San Francisco explicitly allows its residents to keep bees without permits, while other municipalities require written permission from the neighbors. In many cases, beekeepers crawl into the don’t-ask-don’t-tell closet to keep things under wraps.

“I was told to paint the hives green, tuck them between greenery in the corner, and never tell the neighbors,” says Gigi Trabant, who is president of the San Francisco Beekeepers Association and another hobbyist I meet along the way. She began taking beekeeping classes the month after she retired from a career in nursing in 2011. But her attempts at stealth ended when one half of a colony decided to pack up and leave.

“Swarming is a sign of too much success,” she says. “A new beekeeper may not keep track of how fast a colony is growing. When the bees run out of space, the hive splits.”

One warm spring day, thousands of Gigi’s bees whipped themselves into a frenzy and moved en masse across the block in the foggy San Francisco borough of the Richmond.

“And my neighbors actually loved it!” Gigi says, laughing. Today her neighbors count as some of her bees’ biggest champions, inquiring after their wellbeing. But she still takes care to schedule regular hive inspections, which involve opening up the boxes to check for the colony’s health, only on weekdays when her neighbors’ children are at school. And she passes around jars of honey at holidays.

I’ve discovered that few things calm me like having hundreds of bees buzz about me.

For every happy ending like Gigi’s, you’ll hear a nightmare story of miffed neighbors threatening to sue. To avoid such potential conflicts, father and son Anton and Andrzej Krukowski set up their hives away from their home on a dense residential street and used a family friend’s property without neighbors.

Finding the installation site was just the beginning. Andrzej, then only 8, wanted to get over his fear of getting stung by choosing beekeeping as his independent learning project at school. “I was reluctant going in,” says Anton. “I thought it was overambitious for a fourth-grader.”

But Andrzej has the articulate maturity befitting a son of two teachers and approached the project with seriousness.

“Being around bees can be unnerving at first,” says Andrzej, now 12. “When they fly around you and even sting you through the suit, it really does something to your confidence.”

Tending to their hives has become a bonding experience for the duo over the past three years. Lately, though, Andrzej has been feeling a bit unmotivated: “I still enjoy it once we go there, but now it feels more like a responsibility than a privilege. Video games are much easier.”

If his son’s enthusiasm has fluctuated, Anton has grown all the more interested. “There’s something very hypnotic about opening up a hive and seeing them,” he said. “When they’re not overwhelming us, it becomes a meditative activity.”

And I know exactly what he means. Sure, it hasn’t been smooth sailing: I’ve gotten stung, including once on the forehead that ended up growing a tumor-like swelling. Battling ants is a constant struggle, and during one routine check, I dropped a frame full of honey, destroying months’ worth of bees’ labor in one smash. Late in the season, my hive came down with an epidemic of varroa mites, the common parasites that feed on the young, destroying colonies when untreated.

But to my surprise, once I got over my initial anxiety, I’ve discovered that few things calm me like having hundreds of bees buzz about me. Ever the reluctant Californian, I’ve never been one to use words like mindfulness, but beekeeping gives me a taste of the serenity that meditation enthusiasts extol. The bees’ murmur drowns out all the competing thoughts in my head — about the home renovation that’s going all wrong, loved ones’ recent health diagnoses, and work deadlines crashing down on me at once. Even at the end of the worst day, I calm down when I sit by the hive and watch the bees at work, gracefully taking off and soaring along the paths only decipherable to them. When I need comic relief, I look out for the ones returning home, heavy with nectar or pollen. They collide with others or miss the landing by an inch, comically traipsing down before floating again.

In a few short months the bees have provided more solace than any electronic gadget or self-help book. They let me feel at one with nature and time, as I watch them sustain the world, one flight at a time. I breathe without thinking about anything at all, and soon I realize I can simply be. It’s a cliché, I know, but by adopting these rescued creatures, I was saved.

Chaney Kwak is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Condé Nast Traveler, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times, among others.

To learn more about keeping bees, contact your local beekeepers association. You’ll find a directory at beeculture.com/directory.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com.

Does Our Primitive Survival Instinct Still Work in the 21st Century?

Our survival instinct, which has served us so well since we climbed out of the primordial muck eons ago may now be failing us. Why? Because the fight-or-flight reaction that arises in response to a threat to our lives is often no longer effective in a world that is far more complex, unpredictable, and uncontrollable than that of our primitive ancestors’ from which the survival instinct arose. In this article, I want to explore this disconnect between our survival instinct and what kind of new survival instinct might work better today.

At the heart of fight-or-flight are what I call the “Big Three” crisis reactions : fear, gloom, and panic.

Fear

First, the emotional reaction of fear is instantaneous and intense, ensuring that we pay attention and respond to a perceived crisis. In other words, fear causes us to act fast! Fear paralyzes our ability to think clearly, identify problems, and make deliberate decisions because thinking takes time and there just wasn’t enough time back in the cavepeople days for that; the only viable options were to fight or flee, immediately!

Unfortunately, many of today’s threats can’t be fought because there is no readily confrontable enemy (think terrorist attacks, climate change, and job loss). And they can’t be run away from because many are diffuse rather than localized; you can run, but you can’t hide. And burying your head in the sand may work for ostriches, but for humans, it leaves a very important part of the body exposed!

Gloom

Second, gloom can work if the crisis is clear and present. In prehistoric times, focusing on the negative dimensions of a threat — namely, what can go wrong in the near term — ensured that we stayed vigilant to the most relevant dangers, allowing us to respond most quickly. By focusing on the negative aspects of the crisis during primitive times, our ancestors had the simple choice of fighting or fleeing. These primitive threats were also usually short lived — for example, an attacking animal or rival tribe — so gloom had no long-term implications.

But today’s crises are often amorphous, distant, and long lasting. So the initial gloom, which had short-term survival benefits, can become a self-fulfilling prophecy that can worsen the threat. We saw this play out during the Great Recession. Many people distrusted the stock market, many businesses had little confidence in their own survival, and governments lost faith in their ability to overcome the crisis. In all these cases, an attitude of gloom led to behavior that may have actually worsened the financial crisis.

Panic

Third, panic produces immediate and frenzied behavior. Panic was quite functional back in prehistoric days because it triggered in our ancestors either a furious attack or a frantic retreat from the threat. Panic in reaction to many of today’s crises, however, produces actions that are more ill-advised and destructive than helpful. Where there should be patience, there is haste. Where there should be reasoned deliberation, there is irrationality. Where there should be calm, there is, well, panic.

In the panic after the fall of the investment bank Lehman Brothers and the stock market crash that followed, many people fled the financial markets, many businesses drastically cut costs by letting go of employees, and governments went into austerity mode at the worst possible time. All of these efforts were intended to ensure everyone’s respective survival, but such panicked behavior was short-sighted and had the exact opposite effect in the long run.

A New Survival Instinct

If these instincts that are so deeply woven into our DNA no longer fulfill our most basic needs to survive, what new form of survival instinct do we need to evolve to help us to endure in the concrete, metal, and hard-wired jungle in which we now live? As with earlier stages of evolution, we need to adapt to our surroundings and produce a response that will be more effective than the fight-or-flight reaction that helped us survive for hundreds of thousands of years.

But we can’t wait millions of years for evolution to do its job and ingrain a new survival instinct in us that is more functional for the modern world. In fact, we can, to paraphrase a well-known adage, take evolution by the horns and bend it to our will with a new survival instinct that is the antithesis of the time-worn fight-or-flight reaction. Instead of overwhelming and uncontrollable fear, a crisis should trigger courage, which isn’t the absence of fear — it’s impossible to not to experience fear in the face of a threat — but rather the ability to confront the fear and act proactively and deliberately despite it. It involves being able to manage negative emotions, such as fear, anger, frustration, and despair, and to generate helpful emotions, including hope, inspiration, excitement, and pride.

Instead of gloom, we should engage in rational thinking that includes calculated risk-reward analysis, in-depth problem solving, and effective decision making. It means being cognizant of the threat, but focusing more on finding solutions to overcome it. In a crisis that encompasses a group (e.g., work, family, team), this reasoned thinking requires that people set aside differences, communicate openly, establish priorities, and work together — because that is the rational thing to do in the face of significant societal crises — to produce answers to the pressing dangers that today’s threats present to us.

Finally, we don’t need to wait for evolution to adapt our survival instinct to today’s challenges. Rather, we already have the capacity to override our primitive survival instinct. We are already capable of experiencing courage, thinking rationally, and acting deliberately. That is the gift that evolution has also given us; it’s called the cerebral cortex.

Tips For Responding to a Crisis

Instead of panic, we should take calm and measured action that is directed and purposeful. This new survival instinct can increase our chances of surviving during periods of crisis. What results is a psychology—what I call an ‘opportunity mindset’— that is diametrically opposed to and entirely more effective than the survival instinct that now dominates our DNA and our lives.

Of course, the real challenge involves how to resist those millions of years of evolution and stop the instinctive flight-or-flight reaction before it takes complete control of us. Here are a few tips for ingraining a more evolved response to a crisis:

- Stop!: Instead of a knee-jerk reaction to a threat in your life, take a break and gain some physical and emotional distance from the threat. With this separation, your survival instinct will diminish and make it easier for you to engage the higher-order thinking of your cerebral cortex.

- Relax: When your survival instinct is triggered, it activates your ‘sympathetic nervous system’ which puts your body into overdrive with increased heart rate, blood flow, and adrenaline. This reaction helped in the past, but doesn’t do much good with most present-day threats. Take some deep breaths, relax your body, and center your mind.

- Seek support: Crises of all sorts, whether a saber-toothed tiger or the loss of a job, are more manageable when you know that you have others in your life who can support you. So, when a threat arises, look for people who can provide you with emotional and practical support to address the crisis.

- Focus on what you can control: The nature of many of today’s threats is that they aren’t always within your control. But, there are always some aspects of a crisis that you can control, most notably, your reaction, attitude, and response to it. When a crisis arrives, identify what you can control about it and direct your attention there.

- Identify the problem/find a solution: At the heart of every crisis is a problem. If you can identify the problem, you may be able to find a solution to the crisis (of course, not all present-day crises have immediate solutions to resolve them).

- Set goals/make a plan: Crises often result in feelings of loss and destabilization, both of which are truly unsettling. Goals and a plan can provide you with clear direction and tangible steps to overcome the crisis with which you are faced.

- Take action: When presented with a threat, running away from it rarely works these days. Not only is the crisis still there, but you feel even more helpless to confront it. Rather than withdrawing from the threat, choose to take action aimed at overcoming it. You’ll feel more in control, less stressed, and, the big bonus is that you may actually resolve the crisis and remove the threat.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

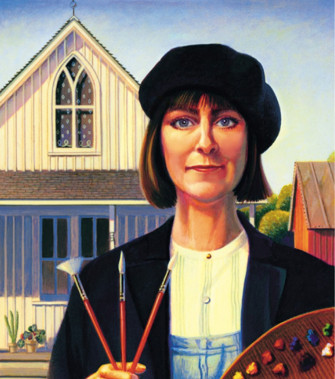

An Interview with Our September/October 2019 Cover Artist Robin Moline

Saturday Evening Post: Can you tell us more about what inspired you to paint the image that appears on the September/October 2019 cover of The Saturday Evening Post?

Moline: This painting was originally commissioned for tapestry art, but I decided to go ahead and create an image that I could also sell for prints and as a stock image. So I basically went to town, put myself into the scene and tried to imagine what the look and the feel of that kind of day would be. The painting had to tell the story and transport the viewer there too.

Post: You describe your style as “a surreal look with an often folksy twist.” Many of your illustrations pay homage to or are reminiscent of Grant Wood. I would describe them as “Grant Wood on acid.” What attracts you to that style of illustration?

Moline: I have heard my artwork described like that before. I’d like to think that I take Regionalism imagery and that folksy style and amplify the colors to make my artwork have a more contemporary feel. What attracted to me to this style is hard to say. I suppose first I always enjoyed painting landscapes from an early age and often they were of rural subject matter of places I’d been and farms I visited. When I first saw Grant Wood’s work I felt a connection maybe because they felt familiar and maybe because I always wanted to be in his paintings. I eventually bought a Grant Wood art book, studied it a lot, and decided I wanted to try to paint like that myself. So I did and eventually it has become what you see today.

Post: Who else are you inspired by?

Moline: There are other Regionalist artists’ work I also really love. Marvin Cone’s sensual landscapes of that same area in Iowa are spectacular. The color and movement in John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton’s work I always find inspirational. Other non-Regionalist artists that stand out are the whimsy, detail, and subject matter of Charles Wysocki paintings. Some of my early favorites were the surrealist Artists Henri Rousseau, René Magritte and Salvador Dalí and the romantic look and thermal colors palette of Maxfield Parrish. I of course enjoy a wide range of artists going back to other centuries as well. While on my honeymoon back in 1980 I saw Botticelli’s large scale paintings and was in total awe. Recently while in Italy I saw again the work of Pinturicchio and his mythological scenes and detail in Sienna’s Duomo; I could have looked at that artwork all day long. Of course there are plenty of other artists to draw inspiration from including many peers but the above stand out in the top tier.

Post: What media do you typically work in?

Moline: My traditional style is I paint on illustration board. I generally do an acrylic airbrushed underpainting then go in with fine tiny acrylic brushes to finesse the art and add detail and texture.

Post: How did you get started in your illustration career?

Moline: I pretty much decided to freelance right out of my college years at The Minneapolis College of Art & Design. I was lucky to start out when I did. There was a lot of local work and I was able to get a representative early on. In the ’90’s after I had established a more consistent style and fine-tuned my skills, I then looked for a national representative and broadened my field.

Post: How is painting for yourself different from painting for a client?

Moline: I do enjoy both. I love the challenge of working with a client and the problem solving involved, whether it be a book or magazine cover, an editorial, a poster, map, or product design. I always love seeing the end result when a client is involved because I am working with other creatives and my work gets to be woven into a bigger picture. I also don’t mind a deadline; of course the longer ones are more welcome. When I work on a painting for myself it’s hard to know when to stop, and that can be a problem. Also when I have a set client there is incentive to get the artwork done because I get paid sooner. So that’s a big motivation as trite as that might sound. Of course painting for myself I only have myself to please and I can experiment and not have a client expecting that specific look they are after based on seeing previous work.

Post: What is your favorite thing about being an artist?

Moline: Honestly being my own boss and working out of my home and not dealing with a commute is the best. Working with so many wonderful creative people I’ve met along the way and that there is always a challenge and rarely a dull moment. Being an artist has made me grateful that I have a way to express myself and that it has allowed me to expand my imagination. Hopefully through my work I can move others emotionally and intellectually and to be able to share some of my inner world and imagination.

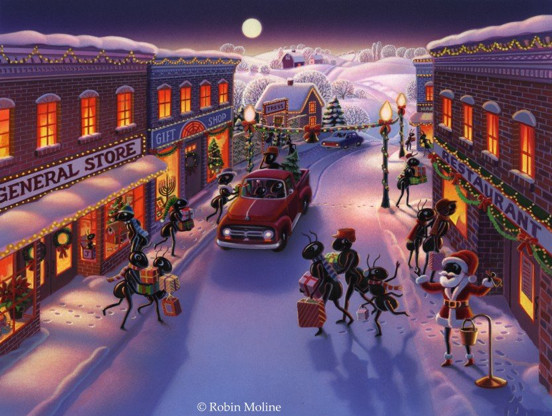

Post: What’s the most fun thing you’ve painted?

Moline: That’s a hard one to pick over the 40 years of painting. So I’ll give you a few that achieved a few levels of satisfaction. The Farmer’s Market Stamp project stands out…I loved the art director and I had a luxurious long deadline. It was first thought that I’d be doing some of my signature landscapes, but in the end I was painting every kind of fruit, vegetable, food, and plant you might find at a neighborhood farmer’s market. It was definitely a job that evolved over time, but I enjoyed the whole process and it also included a trip for the unveiling ceremony in Washington, D.C.

As far as landscape art goes I was lucky to work with HOK architects/engineering in the early ’90’s and did some big projects with them. The second was mural art for the new John Deere Pavilion in Moline, Illinois. The actual painting is a bit of a blur — the deadline was pretty fast considering the amount of painting involved, but the end results still please me to this day. I also fondly look back at an ongoing series I did for a high profile marketing group out in Hollywood called the Ant Farm. I created a group of ant characters for them that were pretty busy and active doing fun things mostly taking place out in L.A. Again, the clients were great to work with, too.

Post: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Moline: Patience and practice above all. You are not going to know your full potential, hidden talents, or fine tune your artwork right away. That takes time. Your artwork, as life itself, is an evolving process…and a gradual unveiling of yourself and your story. Don’t be afraid to experiment with different mediums and subject matter. You will make mistakes and you might disappoint those you work with now and then but you will learn from that. Don’t fear those periods of time when you don’t feel an ounce of creativity surfacing. When that happens, it will take time to observe and reflect and do whatever else you are being pulled toward…travel, read, relax and pick it up again when you are reenergized and the creative tap starts flowing again. Whatever you do don’t compare your work to others… if you are enjoying what it is you do and are growing as an artist, that is number one. Also accept that not everyone is going to like your art. Some will be critical, but if you love your work and you find a niche and even a few people love what you do as well, then you’ve made it. At that point smile and pat yourself on the back!

Post: Is there anything else you’d like Saturday Evening Post readers to know about your work?

Moline: Looking back on my career, a day that tickled me the most was when I was Googling some of Grant Wood’s work, my image came up and someone had mistaken it as his. Just last year I was asked to do a show down at the American Gothic House in Eldon, Iowa. That was another highlight of my career — to be standing in front of that house that had been parodied endlessly, and that my work that was on display inside was inspired by my favorite muse. I’ve told numerous people before that in fun I like to call myself Robin Wood. I think it has a nice ring.

To find out more about Robin and her work, visit robin-moline.pixels.com/.

Featured image: Robin Moline / SEPS.

Cartoons: Play Ball!

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Max Porter

August 16, 1952

J. Monahan

August 16, 1952

Ray Helle

August 4, 1951

Rea

July 28, 1951

Larry Frick

July 14, 1951

Schus

September 2, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image and all cartoons: SEPS.

Considering History: Emmett Till’s Casket and the Worst and Best of America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the early morning hours of August 28, 1955, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam abducted and lynched Emmett Till near the small town of Money, Mississippi. Till, who had just turned 14 years old a month earlier, lived in Chicago with his single mother Mamie; Mamie’s parents had left Mississippi as part of the Great Migration when she was just two years old, and in the summer of 1955 Emmett returned to the area for the first time, staying with Mamie’s uncle Mose Wright and his family. On the morning of August 24 Emmett and his cousin Curtis visited Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market, where 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant was working by herself; according to Bryant’s testimony at the time, Emmett accosted her both verbally and physically. When her husband Roy returned from a fishing trip on August 27, Carolyn told him her version of the encounter, and he and his half-brother J.W. set out on a mission of revenge and racial terrorism that ended with the brutalizing and murder of Emmett.

Virtually every detail of Till and Bryant’s initial encounter remains in dispute, not least because Carolyn Bryant herself has in recent decades recanted some crucial aspects of her testimony (such as the physical side to the altercation). Roy and J.W.’s lynching of Emmett was never in dispute, yet the two men were acquitted on all charges by an all-white jury in a high-profile September 1955 trial. All those histories tell us a great deal about Mississippi, the South, and America, in 1955 and in our own moment. Yet there is another vital side to our collective memories of Emmett Till, one captured by his moving memorial at the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

The centerpiece of the NMAAHC’s Till memorial is his casket — not a replica, but the actual casket in which Till was buried after his early September funeral in Chicago. The Department of Justice exhumed Till’s remains as part of a 2005 investigation into his kidnapping and murder, and he was re-buried in a new casket; the old casket was stored at the cemetery and discovered in 2009. The NMAAHC, still in development at the time, acquired the casket soon after; as Director Lonnie Bunch III put it, “It is an object that allows us to tell the story, to feel the pain and understand loss. I want people to feel like I did. I want people to feel the complexity of emotions.”

When I visited the NMAAHC with my sons and my parents a couple weeks ago, it was indeed the Till memorial that most affected us all (which is no slight on the whole of this must-visit museum). We did feel that pain and understand that loss, as it’s impossible not to contrast the exhibit’s photos of young Emmett (as a baby, as a young boy alongside his mother, and as a smiling teenager just months before his murder) with the photos and stories of his lynching and, most potently, with that adolescent-sized casket, past which visitors to the memorial walk as if at a funeral service.

As that casket reminds us, the pain and loss of Emmett’s lynching was felt with particular force by Mamie. She had already lived through more than her share of struggle, including her family’s migration, her parents’ divorce when she was 13, and, especially, her abusive marriage with Emmett’s father Louis Till. They were only 18 when they married in 1940, and he was consistently abusive, culminating in his choking Mamie to unconsciousness in 1942 (when Emmett was about 1). After that assault she took out a restraining order on Louis, and when he violated it repeatedly he chose enlistment in the army rather than prison. In July 1945 Louis was court-martialed and executed in Italy for murder and rape, leaving Mamie and Emmett as a pair of survivors, a tight family unit on Chicago’s South Side.

For a parent to lose their child in any way is a tragedy; for Mamie to lose her only child in this sudden and brutal manner is a trauma too horrific to imagine. Yet as the museum’s open casket likewise reminds us, Mamie responded to that trauma with a pair of stunning and crucial choices: making Emmett’s funeral service public and, most potently, insisting on an open-casket service. “I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby,” she argued, and tens of thousands of mourners did see Emmett’s brutalized young body (with photographs being seen by millions more). Mamie then embarked on an NAACP-organized speaking tour, sharing her loss and trauma and son and voice with audiences around the country.

As the NMAAHC’s exhibit highlights in depth, Mamie’s choices became hugely inspirational for the nascent Civil Rights Movement and some of its most significant figures and actions. As Myrlie Evers put it, “Somehow [it] struck a spark of indignation that ignited protests around the world. … It was the murder of this 14-year-old out-of-state visitor that touched off a world-wide clamor and cast the glare of a world spotlight on Mississippi’s racism.” Or, as Rosa Parks put it more succinctly, when describing to Mamie Till herself the moment when Parks refused to move to the back of that Montgomery bus, “I thought of Emmett Till and I just couldn’t go back.”

The recent launch of the New York Times’s 1619 Project has prompted renewed debate about whether and how to remember our nation’s most violent and oppressive histories. Critics of the project (those not blatantly advancing white supremacist talking points) argue that dwelling on these painful histories is divisive and destructive to our present and future. Yet until we can feel the pain and understand the loss, how we can possibly grapple with not only the histories themselves, but the nation that has featured them so consistently and centrally? We can only do so by standing before the casket — and when we do, we can also remember the ways in which figures like Mamie Till, Rosa Parks, and so many more have experienced and yet transcended our worst, modeling the best of what we might still become.

Featured image: Emmett Till with his mother, Mamie Bradley, ca. 1950 (Alamy)

“The Thread of Truth, Part IV” by Erle Stanley Gardner

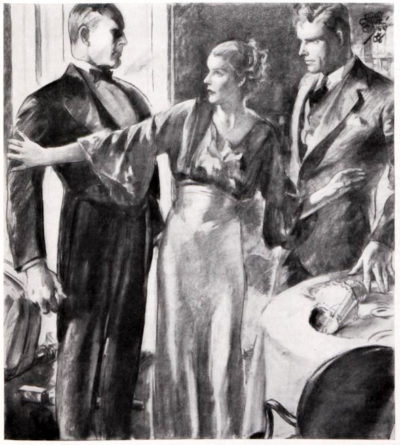

When he died, in 1970, Erle Stanley Gardner was the best-selling American fiction author of the century. His detective stories sold all over the globe, especially those with his most famous defense attorney protagonist, Perry Mason. His no-nonsense prose and neat, satisfying endings delighted detective fans for decades. Gardner wrote several stories that were serialized in the Post. In Country Gentleman, his 1936 serial “The Thread of Truth” follows a fresh D.A. in a clergyman murder case that comes on his first day on the job.

Published on December 1, 1936

The shabby little man, registered as The Reverend Charles Brower, died in Room 321 of the Madison Hotel, murdered by a deadly sleeping tablet. District Attorney Douglas Selby of Madison City, elected on a reform ticket, must find the guilty person, for he knew that the Blade, newspaper of the ousted gang, awaited the chance for a vicious attack.

But Mrs. Brower, come from Nevada to the California town near Hollywood, declared the slain man was not her husband. Yet the few effects in Room 321 were all identified with Brower, all save an expensive camera, a movie scenario, newspaper clippings of the screen favorite, Shirley Arden, and more clippings relating to litigation over the local Perry estate.

Working desperately, Selby learned that Shirley Arden had been a guest of the Madison Hotel the night of the murder, that a man had called upon her, and that a perfumed envelope containing five $1,000 bills had been left in the hotel safe in Brower’s name.

The Blade screamed for action on the case. Selby questioned Shirley Arden, discovered that her distinctive perfume did not tally with that of the envelope, and that she could not remember clearly the name of the man who had called for her aid in selling his scenario. She convinced Selby of her innocence; she even won his reluctant admiration and his promise of protection against the harm that connection with a murder case would do her career.

Then the first break. Spectacles found in Room 321 belonged to a Reverend Larrabie of Riverbend, upstate California town. It was the name Shirley Arden had been trying to recall! Selby and his staunch ally, Sylvia Martin, girl reporter on the friendly Clarion, hastened to Riverbend to return with Mrs. Larrabie. The slain man was her husband, but his murderer was yet to be found.

Then Brower appeared at the hotel to demand the $5,000 envelope, but refused to talk when taken into custody. Next Selby discovered that young Herbert Perry, one of the Perry estate litigants, had knocked on the door of the minister’s room the night of the murder. And then, to Selby’s dismay, Sylvia Martin pointed out that Shirley Arden had suddenly changed the brand of perfume she used — and the change coincided with the time of the minister’s death.

XIII

Events during the next few minutes moved in a swift, kaleidoscopic fashion.

Frank Gordon entered the office very much excited. There had been a shooting scrape down on Washington Avenue. A divorced husband had vowed no one else should have his wife and had sought to make good his boast with five shots from a six-shooter, saving the sixth for himself. Four of the shots had gone wild. The woman had been wounded with the fifth. The man’s nerve had failed when it came to using the sixth. He’d turned to run and had been picked up by one of the officers.

Held in jail, he was filled with lachrymose repentance and was in the proper mood to make a complete confession. Later on he probably would repudiate the confession, claim the police had beaten him in order to obtain it, that he had shot in self-defense and was insane anyway. Therefore, the police were anxious to have the district attorney present to see that a confession was taken down properly.

“You’ll have to go, Gordon,” Selby said. “This will be a good chance for you to break in. Remember not to make him any promises. Don’t even go so far as to tell him it would be better for him to tell the truth. Take a shorthand reporter with you and take down everything that’s said; ask the man if he wants a lawyer.”

“Should I do that?”

“Sure. He won’t want a lawyer — not now, when he wants to confess. Later on he’ll want a lawyer, or perhaps some lawyer will want him in order to get the advertising. How bad is the woman wounded?”

“Not bad; a shot through the shoulder. It missed the lung, I understand.”

“If it isn’t fatal he’ll plead guilty,” Selby said. “If it kills her, he’ll fight to beat the noose. Get him tied up while he’s in the mood.”

Gordon went out, and Sylvia smiled across at Selby.

“If cases would only come singly,” she said, “but they don’t.”

“No,” he told her, “they don’t, and this Larrabie case is a humdinger.”

The telephone rang.

“That,” Selby said, squaring his jaw, “will be Ben Trask.”

But it wasn’t Ben Trask; it was Harry Perkins, the coroner, and for once his slow, drawling speech was keyed up to an almost hysterical pitch.

“I want you to come down here right away, Selby,” he said, “there’s hell to pay.”

Selby stiffened in his chair.

“What’s the matter?” he asked. “A murder?”

“Murder nothing. It’s ten times worse than a murder,” he said, “it’s a dirty damn dog poisoner.”

For the moment Selby couldn’t believe his ears.

“Come on down to earth,” he said, “and tell me the facts.”

“My police dog, Rogue,” the coroner said; “somebody got him, with poison. He’s at the vet’s now. Doc’s working on him. It’ll be touch and go, with one chance in ten for the dog.”

He broke off with something which sounded very much as though he had choked back a sob.

“Any clues?” Selby asked.

“I don’t know. I haven’t had time to look. I just found him and rushed him down to the veterinary’s. I’m down at Doctor Perry’s hospital now.”

“I’ll come down and see what can be done,” Selby said.

He hung up the telephone and turned to Sylvia Martin.

“That,” he said, “shows how callous we get about things which don’t concern us, and how worked up we get when things get close to home. That’s Harry Perkins, the coroner. He’s been out on murder cases, suicides, automobile accidents and all forms of violent death. He’s picked up people in all stages of dilapidation, and to him it’s been just one more corpse. Tears, entreaties and hysterics mean nothing to him. He’s grown accustomed to them. But somebody poisoned his dog, and damned if he isn’t crying.”

“And you’re going down to see about a poisoned dog?” Sylvia Martin asked.

“Yes.”

“Good Lord, why?”

“In the first place, he feels so cut up about it and, in a way, he’s one of the official family. In the second place, he’s down at Doctor Perry’s Dog and Cat Hospital — you know, Dr. H. Franklin Perry, the brother who stands to inherit the money in the Perry Estate if young Herbert Perry loses out.”

“Well?” she asked.

“I’ve never talked with Doctor Perry,” Selby said. “The sheriff’s office found he didn’t know anything about the man who was killed, and let it go at that, but somehow I want to take a look at him.”

“Anything except a hunch?” she asked.

“It isn’t even that,” he said; “but if that morphine was deliberately mixed in with the sleeping tablets, it must have been done by someone who had access to morphine, and who could have fixed up a tablet. Doctor Perry runs a veterinary hospital and … ”

“Forget it,” she told him. “That whole thing was a plant, along with the letter. Larrabie never took that sleeping medicine. Not voluntarily, anyway. His wife said he never had any trouble sleeping. Don’t you remember?”

Selby nodded moodily.

“Moreover,” she pointed out, “when it comes to suspicions, you can find lots of people to suspect.”

“Meaning?” he asked.

“Meaning,” she said, “that I’ve never been satisfied with this man Cushing’s explanations.

“In the first place, the way he shields Shirley Arden means that in some way she’s more than just a transient customer who occasionally comes up from Los Angeles. In the second place, he didn’t disclose anything about that five thousand dollars in the safe until pretty late. In the third place, he was so blamed anxious to have it appear the death was accidental.

“Now, whoever wrote that letter and addressed the envelope was someone who didn’t know the man’s real identity. The only thing he knew was what he’d picked up from the hotel register.”

“Therefore, the murderer must have been someone who had access to the information on the hotel register. And, aside from what he could learn from that register, he didn’t know a thing about the man he killed. Therefore, he acted on the assumption that his victim was Charles Brower.

“He wanted to make the murder appear like suicide, so he wrote that letter and left it in the typewriter. If the man had really been Charles Brower, nothing would ever have been thought of it. The post-mortem wouldn’t have been continued to the extent of testing the vital organs for morphine. And, even if they had found some morphine, they’d have blamed it on the sleep medicine.

“Now, the person who would have been most apt to be misled by the registration would have been the manager of the hotel.”

“But what possible motive could Cushing have had for committing the murder?”

“You can’t tell until you find out what the bond is between Cushing and Shirley Arden. I can’t puzzle it all out, I’m just giving you a thought.”

His eyes were moody as he said slowly, “That’s the worst of messing around with one of these simple-appearing murder cases. If someone sneaked into the room and stabbed him, or had shot him, or something like that, it wouldn’t have been so bad, but … Oh, hang it, this case had to come along right at the start of my term of office.”

“Another thing,” she said, “to remember is that the person who wrote the letter, and probably the person who committed the murder, got in there from 319. Now, there wasn’t anyone registered in 319. That means the person must have had a passkey.”

“I’ve thought of all that,” Selby said. “The murderer could hardly have come in through the transom, couldn’t have come in through the door of 321, and he couldn’t have come in through the door of 323 — that is, what I really mean is, he couldn’t have gone out that way. He could have gotten in the room by a dozen different methods. He could have been hiding in the room, he could have walked in through the door of 321, he could have gone in through 323. After all, you know, we don’t know that the door wasn’t barricaded after the man had died. From what Herbert Perry says, someone must have been in the room some two or three hours after death took place.

“But when that man went out he had only one way to go, and that was through the door of 319. If he’d gone out through 323, he couldn’t have bolted the door from the inside. If he’d gone out through the door of 321, he couldn’t have barricaded the door with a chair. There was no chance he could have gone out through the window. Therefore, 319 represents the only way he could have gone out.”

“And he couldn’t have gone out that way,” she said, “unless he’d known the room was vacant, and had a passkey, and had previously left the communicating door unlocked.”

“That’s probably right.”