“Television made sports,” says Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine, 92, who came up in the Boys of Summer era. “If there was ever a marriage that you could say two became one, you’d have to give television huge credit for taking the game America has loved right into your living room.”

Eighty years ago, on August 26, 1939, NBC aired the first Major League Baseball game on television. “Red” Barber called the Brooklyn Dodgers-Cincinnati Reds double-header at Ebbets Field, where a pair of “electric eyes” transported grainy black and white images of players about one-inch tall to a Kindle-sized screen.

Big league ballclubs like the New York Yankees were initially leery of the “magical” radio-plus boxes introduced that year at the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows Park. Millions toured RCA’s “World of Tomorrow” showcase — some thought television was a trick.

Dodgers president Larry MacPhail, one of the most enterprising minds of baseball, jumped at the chance to televise the first major league game. As a tradeoff, MacPhail received a free television set for the Dodgers’ press room where reporters and club execs marveled at the screen that brought the game to millions.

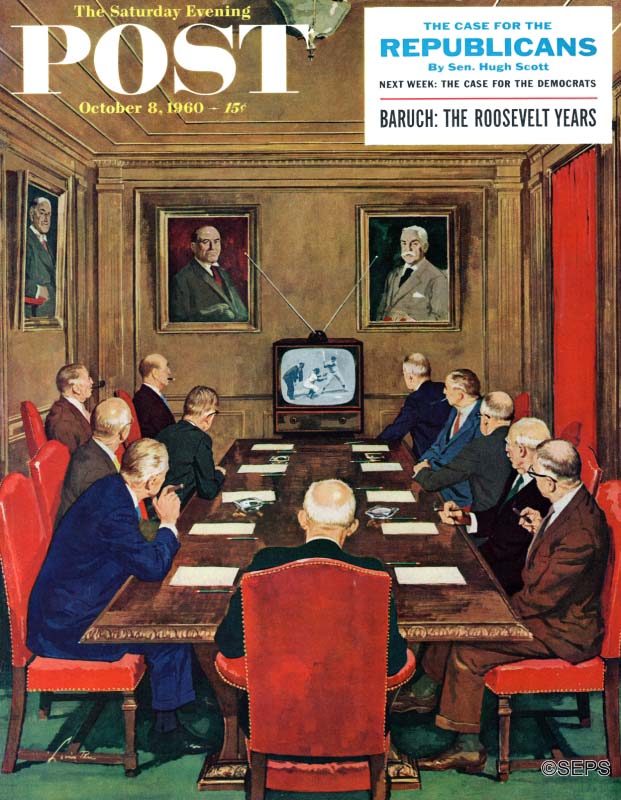

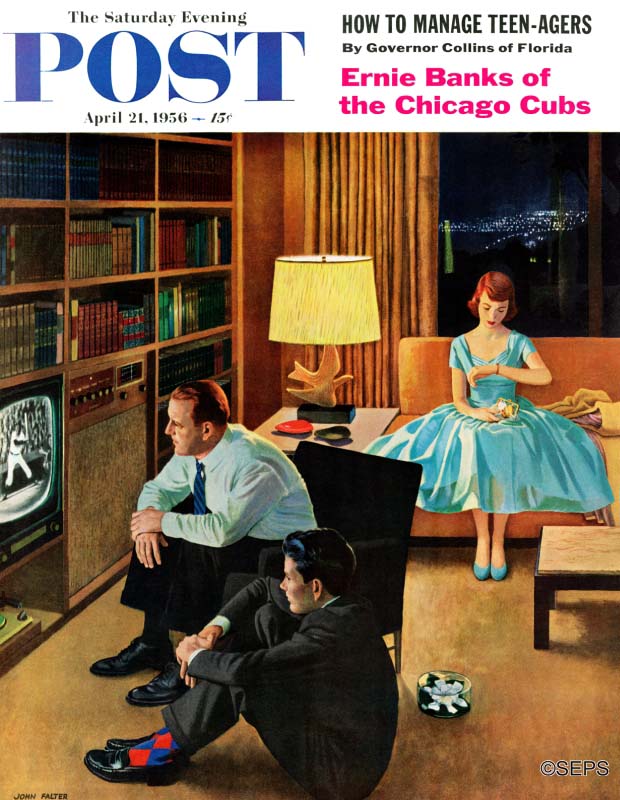

At the time, televisions were mountainous blocks of furniture. Most were located in hotels, private clubs, and dark smoke-filled bars. Using baseball as a sales hook, RCA dealers invited fans into stores for live game-watch parties. The Saturday Evening Post took notice — soon their covers captured Americans transfixed on televised ballgames.

“As with so many innovations at first deemed a threat, it turned out that television was made for

baseball, helping it to grow beyond a regional entertainment that was, until integration and expansion, termed a national pastime,” says John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian.

TV’s Boys of Summer

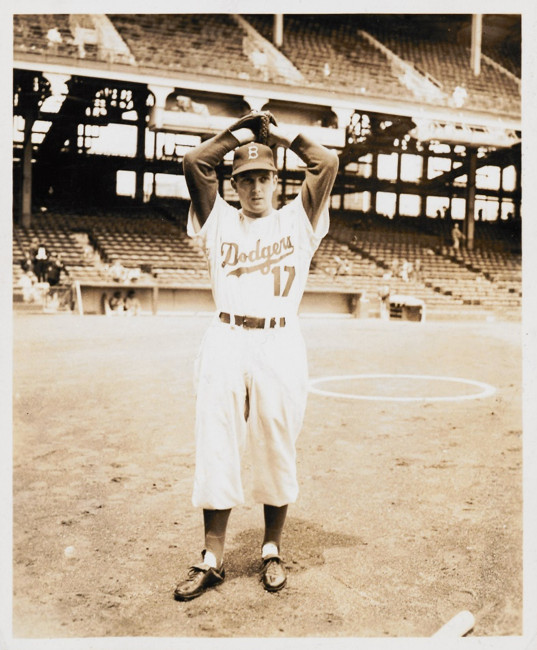

Erskine appeared in 11 World Series games and threw two no-hitters in the 1950s. The Indiana-born pitcher Brooklynites called “Oisk” said players were aware of the cameras stationed behind home plate, center field and the dugouts. But the live coverage “never changed the way we played the game,” he says.

Television did change the design of baseball uniforms. Early Dodgers jerseys had no numbers on the front. Last names were not written on the back, so little red numbers were stitched onto the front left side of jerseys to help television viewers identify players.

According to Los Angeles Dodgers team historian Mark Langill, the new uniforms were ready for the 1951 World Series that never happened. He said Walter O’Malley was not one for focus groups, and his wife chose the color red for the jersey numbers. “It was functional and you can’t go wrong with red, white, and Dodger blue.”

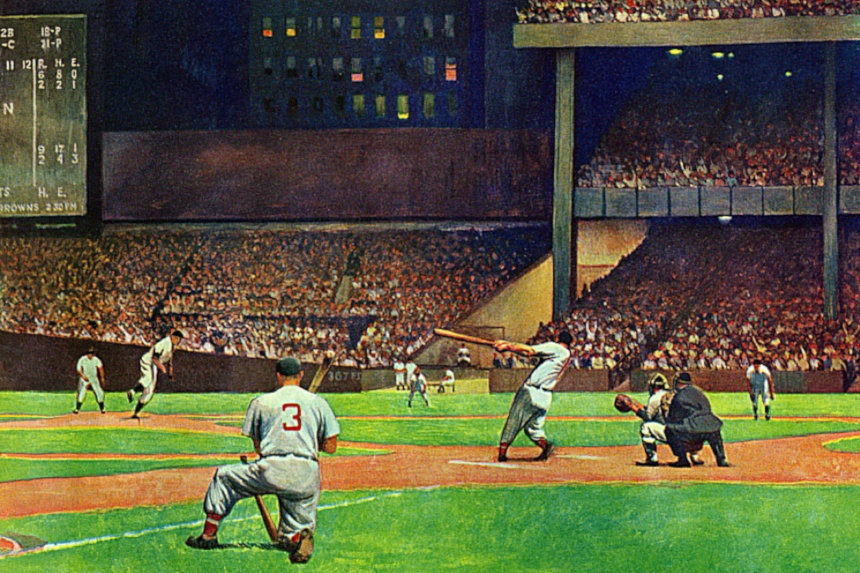

Though Erskine appreciates the chance to watch replays over and over, he feels there’s no substitute for a real game. After attending a recent Triple-A game in Indianapolis, he says, “To see the diamond in the raw is like a beautiful stage. It is perfectly named a diamond – it’s a jewel.”

The Whiz Kid and The Big Easy

Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Bob Miller, 93, is one of two surviving members of the “Whiz Kids” (Curt Simmons, 90, also survives), the young team that unexpectedly won the National League pennant in 1950, facing the Yankees in the World Series. Miller laughed about the first television set he saw in the 1940s when he got out of the Army. “I had to squint to see the screen,” he says, from his home outside of Detroit. When the Phillies won the pennant, departments stores invited all the players to come in for a free suit, new shoes, a topcoat, and a brand-spanking new Philco television set. “Oh, that was quite a thrill.”

The Whiz Kid rates Dizzy Dean and Pee Wee Reese as baseball’s all-time greatest announcer duo. “God, I loved the sound of their voices. They did not oversell the game. If the pitcher didn’t make a good pitch Pee Wee got on Dizzy. If the shortstop booted a ball to the third baseman, Dizzy jumped on Pee Wee. They just had fun together,” Miller says, lamenting how every single pitch and play is analyzed to death on TV today. “At times I feel like a little leaguer at an instruction camp instead of watching the game,” Miller says, trailing off with a laugh. “Sometimes I turn off the sound and watch the beauty of the game.”

Eddie Robinson, 98, signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1942. As one of America’s oldest-living major leaguers, the handsome Texan played for seven of the eight American League teams of his era. Robinson worked as a scout, coach, manager and front-office executive in pro ball from the 1940s through the 1980s. Today he is busy, already 200 pages into his second book where Robinson writes about the wonderous evolution of baseball, seen through the eyes of a player who signed in 1939.

Robinson says he saw his first television set when he got out of the Navy in 1946. The “Big Easy” as he is nicknamed, played against Giants’ hitter Bobby Thomson in the International League. Robinson watched the “Shot Heard Round the World” on a television set in Baltimore, describing his friends’ homerun as a “press-packed moment—one of the best on TV.”

Robinson agrees that there’s no substitute for attending a game. “I still have my ticket stub from Nolan Ryan’s last no-hitter. I’m gonna keep it. My kids will keep it too.”

Featured image: Saturday Evening Post Cover “Yankee Stadium” from April 19, 1947, by John Falter (SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Great feature Ms. Keene on the 80 year marriage between baseball fans seeing their favorite game on television from the comfort of their homes, or other locations of TV accessibility. It’s my personal choice as well for convenience and no risk of unruly, out-of-control “fans” causing problems for others or myself. In addition there’s the risk of getting hit with a baseball I refuse to take. I respect everyone else’s choices that go to the games, and would like the same respect in return for my reasons of not going. If others don’t understand it, I definitely don’t owe any explanation.

It’s interesting here to see covers of the Post depicting people being mesmerized by the new medium for sports, and a lot more that would be one of the key reasons for the deaths of Collier’s and Look magazines. LIFE and the Post also, but the latter two lucky enough to have been revived in new versions designed with less frequency, circulation and the ad dependence the old versions needed as their life blood, vacuumed away by TV. (The 2nd LIFE lasted from 1978-2000).

What television giveth, it also taketh away. Television programming, then and now exists for only one reason: to get you in front of the set to watch the shows so you’ll watch the commercials. Technology has made it possible to zip through a lot of the ads now, true, but not to the damaging extent TV did to America’s peak magazines in the 20th century’s peak decades. Still, it’s virtually an advertising medium only, and that’s not likely to change. Fortunately neither is baseball’s popularity, keeping the baseball/TV marriage strong for years to come.