This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

While not as prominent nor as straightforward as the growing movement to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day, recent years have seen a complementary challenge to how we think about Thanksgiving. For instance, native historian and public scholar Philip Deloria recently wrote a bracing article “The Invention of Thanksgiving,” for The New Yorker, where he discusses both the historical oppression at the time of the so-called “First Thanksgiving” and the ways in which our subsequent collective constructions of that event have too often amplified that oppression.

For last year’s Thanksgiving column, I offered one way to challenge those constructions without discarding the cherished traditions of the holiday: by remembering a figure like Tisquantum and all the histories to which he connects.

Recently, narratives about Thanksgiving have shifted away from the history of the holiday, and toward the broader concepts of gratitude and appreciation for blessings in our lives. And seen through that lens of gratitude, we can remember another lesser-known event that established one of America’s most enduring and inspirational communities, the Mashpee Revolt of 1833.

The Native American community in Mashpee, Massachusetts included the Wampanoag tribe, one of the first to encounter English arrivals in New England. Over the course of the 17th century (despite the six-point peace treaty negotiated by Chief Massasoit with the help of Tisquantum) they suffered some of the most destructive effects of that contact. While that history includes overtly violent events such as the mid-1670s King Philip’s War, it also featured a consistent thread of English settlers taking land and resources from Wampanoag villages. The Wampanoag men and women who endured these incursions and removals, and who survived the epidemics that the European arrivals brought with them, began to gather in “Indian town,” a community that sprang up in the Cape Cod area known as Mashpee.

Yet if the town was created in part out of tragic necessity, it also represented a self-determined and inclusive model for Native American community in post-contact America. Native Americans from other local tribes began to move into the area as well, and in 1665 two Wampanoag chiefs formally deeded the land to this burgeoning, multi-cultural native community. The deed, filed in Plymouth Court, noted that Mashpee would belong to these indigenous inhabitants “forever; so not to be given, sold, or alienated from them by anyone without all their consents thereunto.” The town and community continued to expand and thrive for the next century, and on June 14th, 1763 the Massachusetts General Court officially incorporated Mashpee as a “plantation,” the colony’s designation for a civic space belonging to its local residents. Yet with this recognition came a step backwards in the community’s development: the patronizing appointment of white “overseers.”

Over the next half century, neighboring white settlers took advantage of that status — and of the general atmosphere of exclusion that would culminate in the 1830 Indian Removal Act — to pilfer resources from Mashpee. Firewood was frequently stolen from the community’s forests, and fish and shellfish from its Cape Cod waters. Not only did the white overseers not challenge nor stop these behaviors, but they actively encouraged them, allowing neighboring white farmers to lease grazing land for their livestock and (per the Mashpee community’s frequent and unanswered pleas to the state legislature) keeping the money for themselves. And, in the early 1830s, when a Native American preacher known as “Blind Joe” Amos sought to lead a congregation of those in the town who had converted to Christianity, the state’s appointed white minister barred him from using the meetinghouse, forcing him to conduct his services outside.

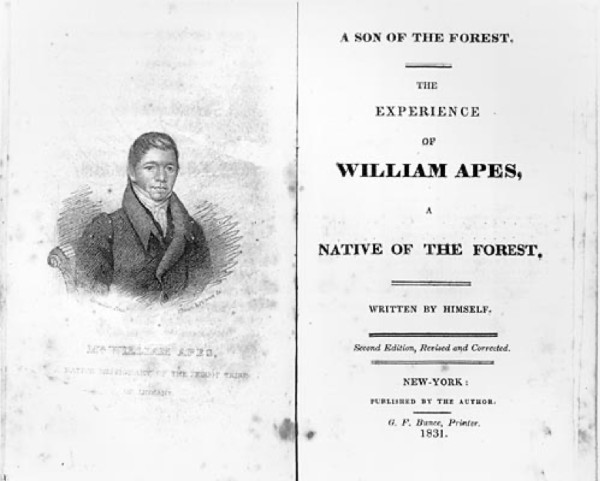

At the same time these injustices were unfolding, an important new presence came to Mashpee: a passionate and eloquent itinerant Methodist minister named William Apess. Apess had spent the last few years traveling throughout New England, preaching to indigenous communities, and speaking and writing about Native American history, identity, religion, and community, blending both Christian and traditional spirituality and stories (such as those of his Pequot ancestors and of King Philip, to whom he claimed relation on his mother’s side) with political and legal arguments. He had heard about the issues facing Mashpee, both religious and territorial, and in early 1833 traveled to the community to see what he could contribute on each of those levels.

Ready to challenge their intrusive neighbors and ineffective overseers, and encouraged by this activist visitor to pursue self-governance, the Mashpee elected a 12-man council. Three of those councilmen, Israel Amos (a relative of Blind Joe’s), Isaac Coombs, and Ezra Attaquin, would later write, in a letter to the state legislature in support of Apess, that “the Great Spirit who is the friend of the Indian as well as of the white man, has raised up among you a brother of our own and has sent him to us that he might show us all the secret contrivances of the pale faces to deceive and defraud us.” The council and tribe had, they added, “all the confidence in him that we can put in any man,” and inspired by that confidence, the council worked with Apess to draft a formal document of protest, a petition sent “to the Governor & Council of the State of Massachusetts” on May 21st, 1833.

That petition, signed by 108 men and women from the community and collectively authored “on behalf of the Mashpee Tribe” and “in the voice of one man,” had two practical purposes: to lodge a series of protests about the abuses perpetrated by both white neighbors and state overseers; and to set a date of July 1st, 1833, as a line of demarcation, after which the tribe would “not permit any white man to come upon our plantation to cut or carry off wood or hay or any other article.” But along with those resolutions was a more philosophical and inclusive statement: “That we as a Tribe will rule ourselves, and have the right to do so for all men are born free and Equal, says the Constitution of the country.”

Both the neighboring and official white communities responded to this document with hostility. On July 1st, the very date set by the tribe as the start of formal resistance, two men from the nearby town of Barnstable arrived in Mashpee to test the tribe’s will by cutting and stealing wood. When tribal residents unloaded their wagon and forced the men to leave, the state responded by siding with the intruders. Apess and a few other men were arrested, charged with “riot, assault, and trespass,” and sentenced to thirty days in jail. Massachusetts Governor Levi Lincoln threatened to muster the state militia if the tribe continued its resistance, and the white press, perhaps angling for military intervention such as President Andrew Jackson’s use of the army to enforce the Removal Act in the Southeast, began to call the unfolding crisis the “Woodlot War.”

The Mashpee tribe did not meet this provocation with violence, but neither did they back down from their protests and demands for equality. As Apess would later write in his book Indian Nullification of the Unconstitutional Laws of Massachusetts, Relative to the Mashpee Tribe; or, The Pretended Riot Explained (1835), “All that the Indians want in Mashpee is to enjoy their rights without molestation. They have hurt or harmed no one. They have only been searching out their rights, and in so doing, exposed and uncovered, have thrown aside the mantle of deception, that honest men might behold and see for themselves their wrongs.” That sentence’s final clause is particularly important, for as Apess argues in his book’s conclusion, the success of the Mashpee Revolt (as it would come to be known) depended on garnering more sympathetic and inclusive responses from powerful potential allies in the state: “it was necessary, for their future welfare, as it depends in no small degree upon the good opinion of their white brethren, to state the real truth of the case, which could not be done in gentle terms.”

Fortunately, the petition and protests, as well as the continued activism of Apess and others, did find sympathetic audiences. A first step was securing a friendly journalistic voice to counter the exclusionary press narratives, and Apess found one in Benjamin Hallett, journalist, lawyer, and rising star in the state’s Anti-Masonic Party. His advocacy helped convince the state legislature to send a delegation in late 1833 to investigate conditions in Mashpee, and they produced a lengthy report indicting the white overseers and supporting the tribe’s positions. On January 21st, 1834, Apess and other tribal leaders journeyed to Boston to address a special evening session of the legislature, and four days later the abolitionist activist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison took up the cause in an editorial in his newspaper The Liberator.

On March 31st, 1834, the tribe won a crucial victory: the legislature voted to abolish the community’s white guardianship and turn Mashpee into a “district,” giving its residents the official power to elect their own government and manage their own affairs. This step note only granted the Mashpee tribe the sovereignty for which it had been fighting but also recognized it as a community much like other self-governing Massachusetts towns; indeed, Mashpee would be incorporated as a town in 1870, and remains one to this day. Over the last few years, however, Mashpee has once again been threatened, this time by Trump administration policies that seek to keep the tribe from building a casino (and as part of a broader attack on Native American tribal sovereignty). As with so many inspiring American histories in 2019, remembering and appreciating this one means also fighting for its present rights and future existence. I can think of no more apt way to celebrate Thanksgiving.

Featured image: King (Metacomet) Philip, Sachem of the Wampanoags, 1676, full length, standing at treaty table (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now