When Louis and Bebe Barron moved to Greenwich Village in 1948, they didn’t consider themselves composers. In fact, it would be years before mainstream sources understood their creations to constitute music.

As a wedding gift, the couple received a German tape recorder, one of the first magnetic tape recorders ever made, and so they set about learning to manipulate audio to create bizarre and entrancing soundscapes. In New York, the Barrons found themselves in the middle of a burgeoning avant-garde music scene. The couple worked alongside important electro-acoustic composers and pioneered music-making with computers, along the way making the first electronic score for a major movie in Forbidden Planet.

The process of creating electronic music in the 1950s wasn’t as straightforward as it is today. After all, the Barrons didn’t have music software or even a modern synthesizer. What they did have was a studio filled with recorders and homemade equipment. Louis’s oscillators and circuits could produce various tones as he would overload them and record the results. As time consuming as his initial recording process was, Bebe’s job of splicing tape and rerecording the audio with reverb and speed manipulation took even more time. The couple worked this way for years, creating and sorting through their own library of sounds to score short avant garde films. Since they had a relative at Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Company (3M), they were always in supply of tape. They made money off their studio by recording poets and authors like Aldous Huxley and Tennessee Williams.

In 1955, they received the opportunity to score Forbidden Planet, a studio sci-fi film. Only, they weren’t credited for providing a score but rather “electronic tonalities,” an acquiescence to the musician’s union that represented all of the composers and instrument players who weren’t required in the Barrons’ process.

The soundtrack of Forbidden Planet subverted the expectations of movie-goers as it was a new hybrid of sound effects and score. The otherworldly beeps, whoops, and echoing tones were beautiful and unsettling for audiences, and dissonant industrial-sounding compositions expressed a new kind of aural atmosphere impossible to create with a live orchestra. The Barrons had done it all with careful manipulation of electrical currents and thoughtful editing.

Uploaded to YouTube by YouTube Movies

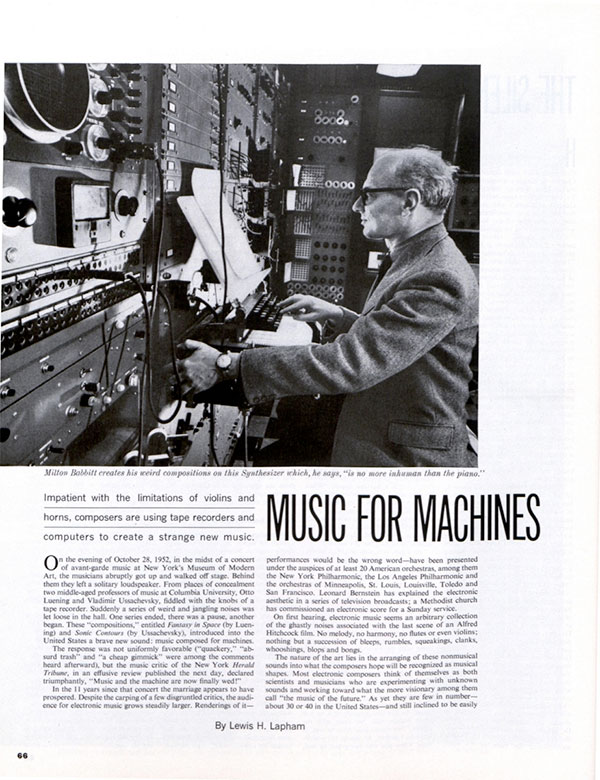

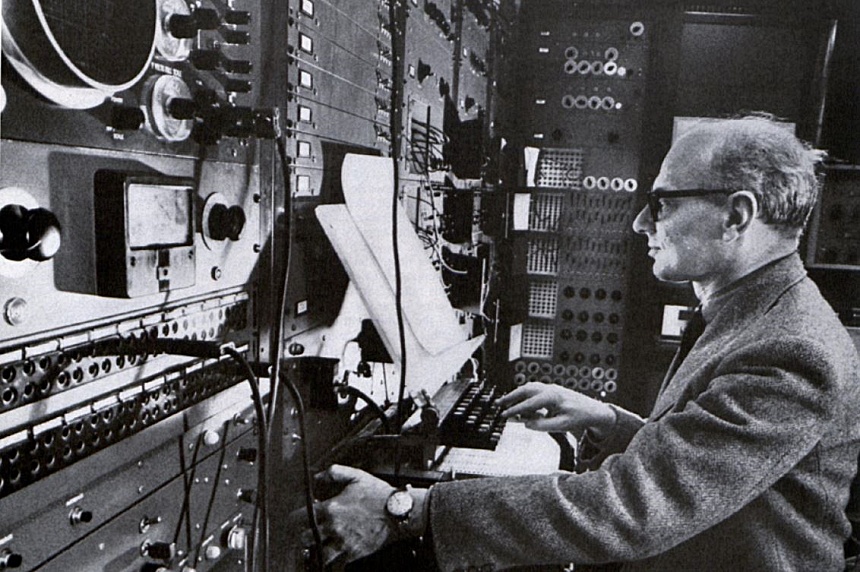

Years later, in 1964, The Saturday Evening Post covered this strange, new kind of “music” in Lewis Lapham’s “Music for Machines.” Though the article left out the Village D.I.Y.ers Louis and Bebe, Lapham’s report covered some other notable electronic composers, like John Cage and Milton Babbitt, who had worked closely with the Barrons in their studio. By the ’60s, large professional synthesizers had been built in universities, but the process for sound engineering was still laborious:

Musical composition for magnetic tape compares with the making of a mosaic. Single fragments of sound are first recorded on separate bits of tape. The sounds can be natural (rushing wind, the sea, buses colliding) or artificial (sine waves, square waves or “white noise” generated by oscillators). Once recorded, every sound can be modified or transformed by electronic filters or reverberators. Finally, the composer decides on the sequence in which the single sounds are spliced together. “Not the sort of thing,” [Vladimir] Ussachevsky said, “that one goes away whistling.”

Because American electronic music had risen from underground creative circles — and it was still largely relegated to the modern art world and academia — there were still many questions around the space age sounds that computers could create. What would become of performers? Is it actually music?

When The New York Times reviewed Forbidden Planet, the paper noted the contributions of its composers, but stopped short of addressing them as such: “Louis and Bebe Barron … developed the ‘tonalities’ — the accompaniment of interstellar gulps and burbles — that take the place of a musical score.”

It would be years before electrical gulps and burbles would be widely recognized as music. Years of advancement, influence, and complicated cultural factors would make musical movements like krautrock and techno possible. Now you can’t turn on the radio without hearing electronica.

When the Barrons set out to explore the unknown territory of electronic sound, they couldn’t have known how far the trajectory of their work would sustain. Like any composers, they were only attempting to express in sounds what they couldn’t put in words. In an interview in the ’90s, Bebe recalled the thrilling prospect of working on Forbidden Planet and sharing their obscure music with the world. “People would say to us, your music sounds just like dreams I have all the time,” she said. “That’s what we like best to hear: ‘you’re expressing our subconscious.’”

Featured image: Milton Babbitt creates his weird compositions on this Synthesizer which, he says, “is no more inhuman than the piano.” (Saturday Evening Post, January 18, 1964, photo by Vytas Vilaitis)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

LOVE this article, Nick. It really explains the origins of what I’ve been used to hearing for SO long in music, I never thought about it HAVING an origin; which of course it had to. I love techno-pop (like Kraftwerk) and New Wave that incorporates it in fresh new ways that are unique and exclusive to them, giving them their own ‘trademark’ signature styles. What the Barron’s did was give birth to electronic sounds that could and have, done just that.

As time went on, new technologies per this article, would expand the possibilities even further. I listened to all three videos you included here. I enjoyed them all, but the ‘Bells of Atlantis’ had the biggest ‘wow factor’ for me. I heard elements of Human League instrumentals, Steve Miller’s ‘Abracadabra’ and The Car’s ‘Moving In Stereo’ decades before their existence. In one of them I could even detect the beginning of Robert Plant’s ‘Heaven Knows’.

The Beatles were certainly one of the first to incorporate some of these elements into their music. Really great music uses elements of electronica as an enhancer here and there within the song, but never as a crutch for what is otherwise noise. A great example of this done right in a hard rock song is Deep Purple’s ‘Highway Star’. It takes you on a wild ride but never becomes ‘noise’. It brilliantly weaves all kinds of elements but stays on track.

I haven’t seen Styx and ELO in concert many times for nothing. They deliver the hits I love, never using tech as a crutch to try to disguise a lousy song. For example ‘Too Much Time On My Hands’ uses it here and there as part of the song. ELO has a ‘cascading downward’ effect used to perfection in ‘Shine A Little Love’. Check it out. There are too many examples to cite, so just one more: the entire Car’s album ‘Candy-O.

Thanks for the link that led to Billie Eilish. I wasn’t sure what to think at first, but she’s creative and I want to see more of her videos (hopefully minus any blood). The music is pretty good, and isn’t reliant on exaggerating all the vowels, sung in a crybaby manner; at least not this one. That’s huge, and we need fresh infusions. Music’s been stuck in the same groove for 25 years. Time to shake it up.