Many of my best friends think that some of my deeply held beliefs about important issues are obviously false or even nonsense. Sometimes, they tell me so to my face. How can we still be friends? Part of the answer is that these friends and I are philosophers, and philosophers learn how to deal with positions on the edge of sanity. In addition, I explain and give arguments for my claims, and they patiently listen and reply with arguments of their own against my — and for their — stances. By exchanging reasons in the form of arguments, we show each other respect and come to understand each other better.

Philosophers are weird, so this kind of civil disagreement still might seem impossible among ordinary folk. However, some stories give hope and show how to overcome high barriers.

One famous example involved Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis in my hometown of Durham, North Carolina; it is described in Osha Gray Davidson’s 1996 book (and 2019 movie) The Best of Enemies. Atwater was a single, poor, black parent who led Operation Breakthrough, which tried to improve local black neighborhoods. Ellis was an equally poor but white parent who was proud to be Exalted Cyclops of the local Ku Klux Klan. They could not have started further apart. At first, Ellis brought a gun and henchmen to town meetings in black neighborhoods. Atwater once lurched toward Ellis with a knife and had to be held back by her friends.

Even the best arguments sometimes fall on deaf ears. But we should not generalize hastily to the conclusion that arguments always fail.

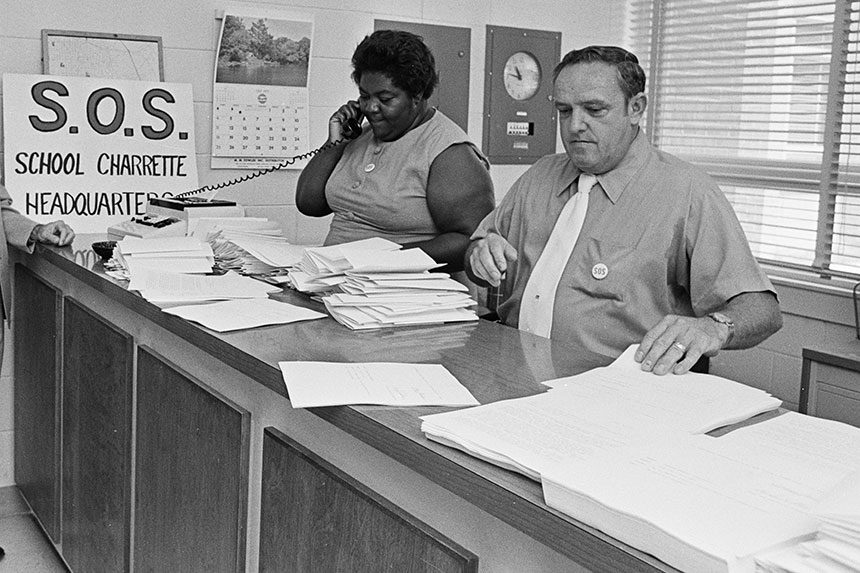

Despite their mutual hatred, when courts ordered Durham to integrate their public schools, Atwater and Ellis were pressured into co-chairing a charrette — a series of public discussions that lasted eight hours per day for 10 days in July 1971 — about how to implement integration. To plan their ordeal, they met and began by asking questions, answering with reasons, and listening to each other. Atwater asked Ellis why he opposed integration. He replied that mainly he wanted his children to get a good education, but integration would ruin their schools. Atwater was probably tempted to scream at him, call him a racist, and walk off in a huff. But she didn’t. Instead, she listened and said that she also wanted his children — as well as hers — to get a good education. Then Ellis asked Atwater why she worked so hard to improve housing for blacks. She replied that she wanted her friends to have better homes and better lives. He wanted the same for his friends.

When each listened to the other’s reasons, they realized that they shared the same basic values. Both loved their children and wanted decent lives for their communities. As Ellis later put it: “I used to think that Ann Atwater was the meanest black woman I’d ever seen in my life. … But, you know, her and I got together one day for an hour or two and talked. And she is trying to help her people like I’m trying to help my people.” After realizing their common ground, they were able to work together to integrate Durham schools peacefully. In large part, they succeeded.

None of this happened quickly or easily. Their heated discussions lasted 10 long days in the charrette. They could not have afforded to leave their jobs for so long if their employers (including Duke University, where Ellis worked in maintenance) had not granted them time off with pay. They were also exceptional individuals who had strong incentives to work together as well as many personal virtues, including intelligence and patience. Still, such cases prove that sometimes sworn enemies can become close friends and can accomplish a great deal for their communities.

Why can’t liberals and conservatives do the same today? Admittedly, extremists on both sides of the current political scene often hide in their echo chambers and homogeneous neighborhoods. They never listen to the other side. When they do venture out, the level of rhetoric on the internet is abysmal. Trolls resort to slogans, name-calling, and jokes. When they do bother to give arguments, their arguments often simply justify what suits their feelings and signal tribal alliances.

The spread of bad arguments is undeniable but not inevitable. Rare but valuable examples such as Atwater and Ellis show us how we can use philosophical tools to reduce political polarization.

The first step is to reach out. Philosophers go to conferences to find critics who can help them improve their theories. Similarly, Atwater and Ellis arranged meetings with each other in order to figure out how to work together in the charrette. All of us need to recognize the value of listening carefully and charitably to opponents. Then we need to go to the trouble of talking with those opponents, even if it means leaving our comfortable neighborhoods or favorite websites.

Second, we need to ask questions. Since Socrates, philosophers have been known as much for their questions as for their answers. And if Atwater and Ellis had not asked each other questions, they never would have learned that what they both cared about the most was their children and alleviating the frustrations of poverty. By asking the right questions in the right way, we can often discover shared values or at least avoid misunderstanding opponents.

Third, we need to be patient. Philosophers teach courses for months on a single issue. Similarly, Atwater and Ellis spent 10 days in a public charrette before they finally came to understand and appreciate each other. They also welcomed other members of the community to talk as long as they wanted, just as good teachers include conflicting perspectives and bring all students into the conversation. Today, we need to slow down and fight the tendency to exclude competing views or to interrupt and retort with quick quips and slogans that demean opponents.

Fourth, we need to give arguments. Philosophers typically recognize that they owe reasons for their claims. Similarly, Atwater and Ellis did not simply announce their positions. They referred to the concrete needs of their children and their communities in order to explain why they held their positions. On controversial issues, neither side is obvious enough to escape demands for evidence and reasons, which are presented in the form of arguments.

None of these steps is easy or quick, but books and online courses on reasoning — especially in philosophy — are available to teach us how to appreciate and develop arguments. We can also learn through practice by reaching out, asking questions, being patient, and giving arguments in our everyday lives.

We still cannot reach everyone. Even the best arguments sometimes fall on deaf ears. But we should not generalize hastily to the conclusion that arguments always fail. Moderates are often open to reason on both sides. So are those all-too-rare exemplars who admit that they (like most of us) do not know which position to hold on complex moral and political issues.

Two lessons emerge. First, we should not give up on trying to reach extremists, such as Atwater and Ellis, despite how hard it is. Second, it is easier to reach moderates, so it usually makes sense to try reasoning with them first. Practicing on more receptive audiences can help us improve our arguments as well as our skills in presenting arguments. These lessons will enable us to do our part to shrink the polarization that stunts our societies and our lives.

This article was originally published by Aeon Media Group Ltd. It is also featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: The best of enemies: Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis, longtime adversaries, were surprised to find common ground when they co-chaired a community summit

on desegregating Durham schools. (Photo by Jim Thornton, courtesy The Herald-Sun Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Joshua, I don’t think the idea was to equate the two. The idea is to talk. People with jobs are often busy do not get all the facts and they gravitate toward family and friend views. The greatest danger is the habit now of taking everything on the internet and all of the news as the truth. The truth takes lots of digging and listening. That is the point she is trying to make. Ellis did not even consider her point of view until he decided to listen. It is an example of showing humility. I totally love the fact that you mentioned the guns brought to neighborhood meetings. They should not be tolerated at voting places either. One tends to overlook the transgressions of our own. The violence against black women for example, perpetrated by black men. The gang violence that exists in black neighborhoods. We can excuse ourselves as victims of our circumstances, but it always goes both ways. Listening and being peaceful in your argument, and presenting it with humility for our own mistakes helps. I am a moderate. I hope I am a listener. Determining what is right takes lots of reading and listening. I especially like sources who can be sued if they are incorrect. I am not a tribalist, and am not afraid to stand for what is right, even if I stand alone. Mr. Trump tried to change the election outcome on his own. He should not be in our political system. That is not who we are. I still think there is room for everyone to succeed.

The Saturday Evening Post should be *ashamed* of itself for publishing an article that attempts to equate Ann Atwater, “a single, poor, black parent who led Operation Breakthrough, which tried to improve local black neighborhoods” with C. P. Ellis, a member of the Klu Klux Klan (a terrorist organization historically noted for its beliefs in white supremacy, anti-Semitism,homophobia, and racism; not to mention the murders of countless Americans of color) who “brought a gun and henchmen to town meetings in black neighborhoods.”

Walter S. Armstrong tries and fails to espouse the ludicrous notion that there are “good people on both sides.” This is not a grey issue. It is a solid case of right versus wrong. And trying to paint Atwater as an “extremist” comparable to that of someone like Ellis, who, again, was a KKK member is not only misinforming and dishonest but absolutely deplorable. Again, *shame* on the SEP for publishing such a tone deaf article in the midst of a national protest against the mistreatment of people of color.

And while I understand that the May/June issue was published before the May 25th death of George Floyd and the national protests his death sparked, that is still no excuse to allow such a distasteful piece to be published in the era of #BlackLivesMatter. You could’ve retracted and denounced that article in your July/August issue – but you didn’t.

All arguments on both sides have been spouted for decades. However, when a country is laying on the ground bleeding to death, it is not the time to ask whom shot the bullets. Right NOW, we need to call the EMTs . In other words. To heal or at least start the process.

In reply to Terry> If she was truly listening, she’d realize both sides have issues. I believe terry is too single minded to even begin to understand what is happening to our country. Whe I have a discussion with republican neighbors and sfter they tell me how great trump is doing, I then ask to give me some examples. Invariably, I get either none or he made economy great. If I mention that Obama’s administration went far to save jobs and improve the economy, they turn away or mention how corrupt Hillary Clinton is. At that point discussion ends. There is so much to dislike about the current administration from my viewpoint and they don’t see it. Sometimes they’ll respond with name calling- Obummer or I must be a Libtard. At this point, I’m finished and realize the schism is too great and we’ll never ever see eye to eye. I get exhaused with these outcomes.

Wouldn’t a stupid, fetid racist pig like you be a better target? I know what you want for your community–you want all the non-whites to leave. Well, you’ll be packing up first.

Ya, make sure you send copies of this to all the liberal media,the DNC, all large city Mayors and Assemblies, the ACLU…and I could go on. Have you people heard the disgusting,unending,shrieking,filthy mouthed and written tirades against any conservative,any one in the Administration, and BLACK conservative, and conservative assembly, any sensible Governor or Mayor, any opinion poll not agreeing with them–I mean for God sake it is nauseating and putrid. So tell THEM!!!!!