Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

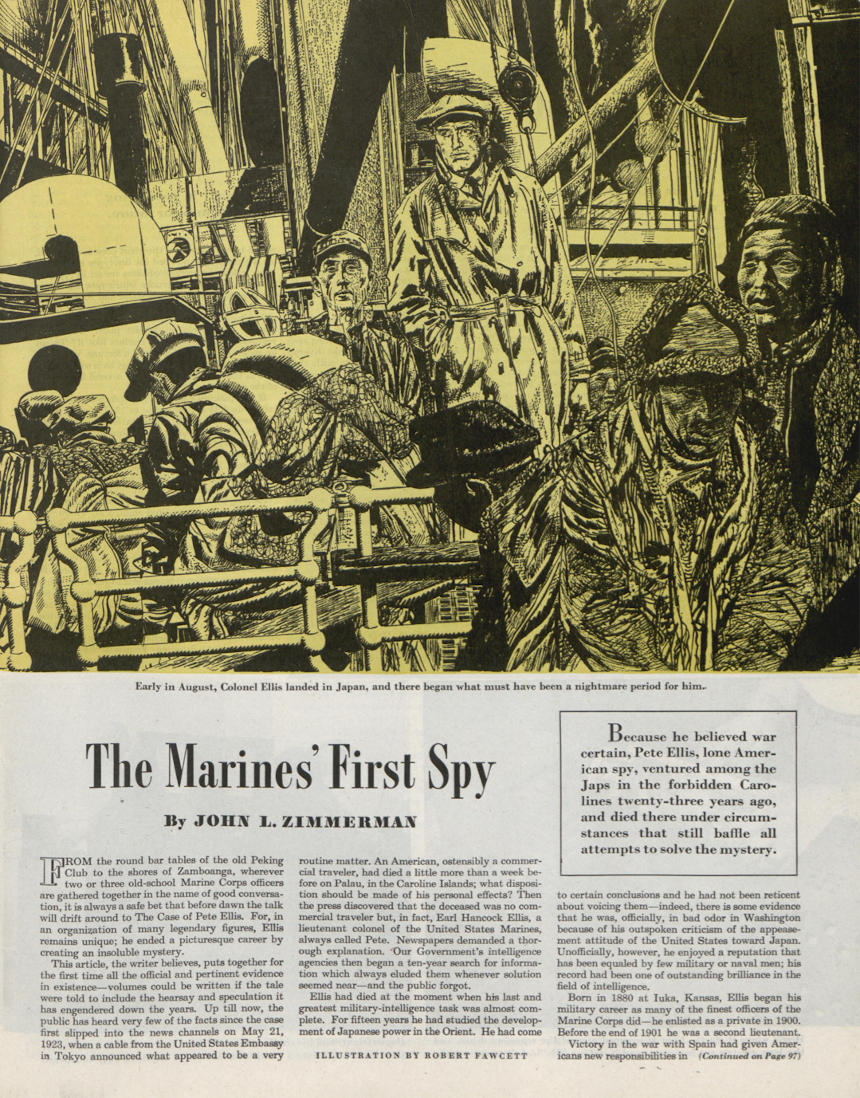

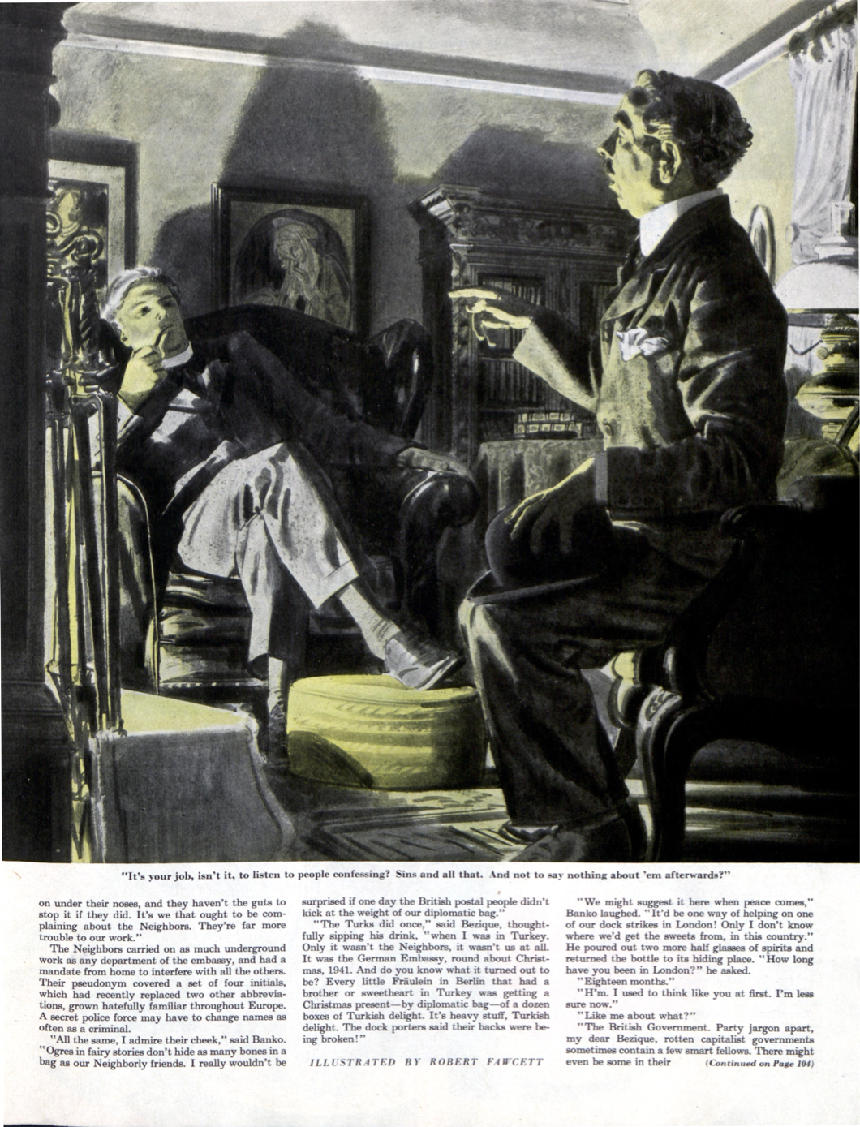

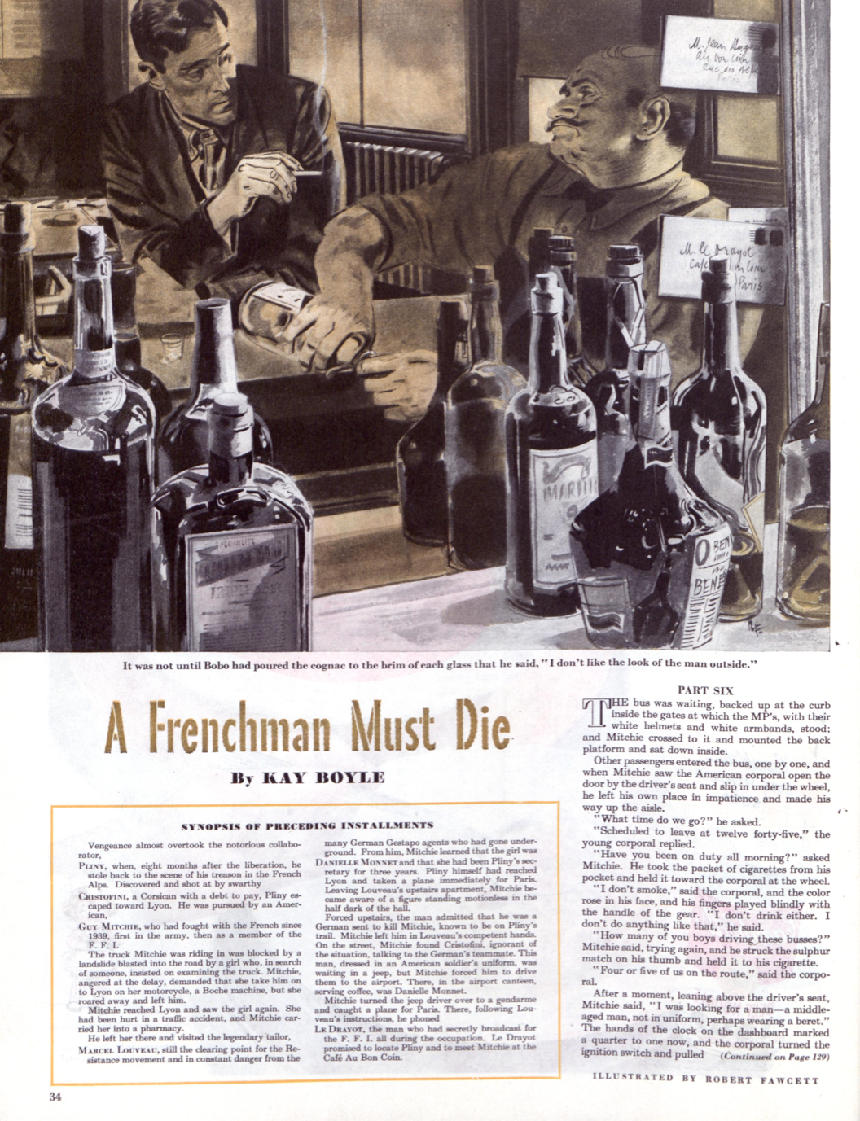

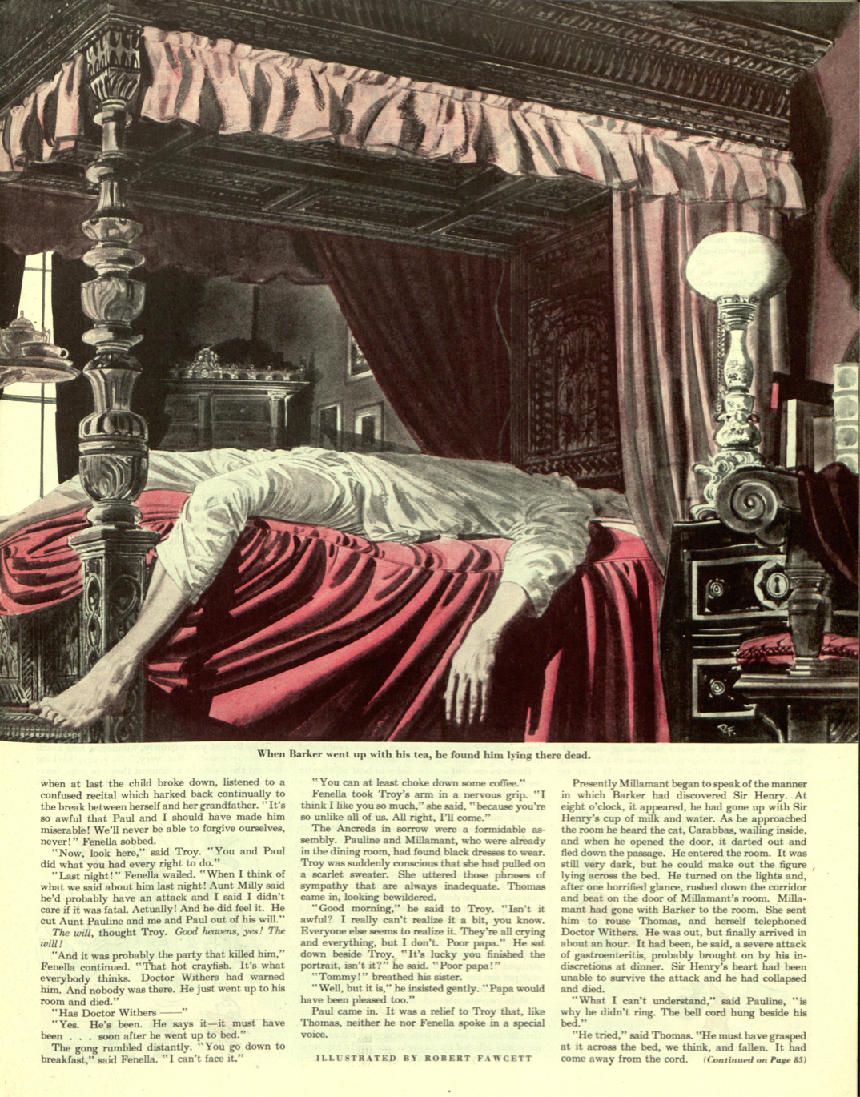

Robert Fawcett illustrated for The Saturday Evening Post in the 1940s and ’50s. He was known as one of the best draftsmen in American illustration…also one of the most prickly.

Fawcett had no patience for diplomacy. Brilliant, opinionated, and candid, he had strong views about everything from art to politics, and was fearless about expressing them, whether people wanted to hear them or not. Friends recalled that he could be quite intimidating.

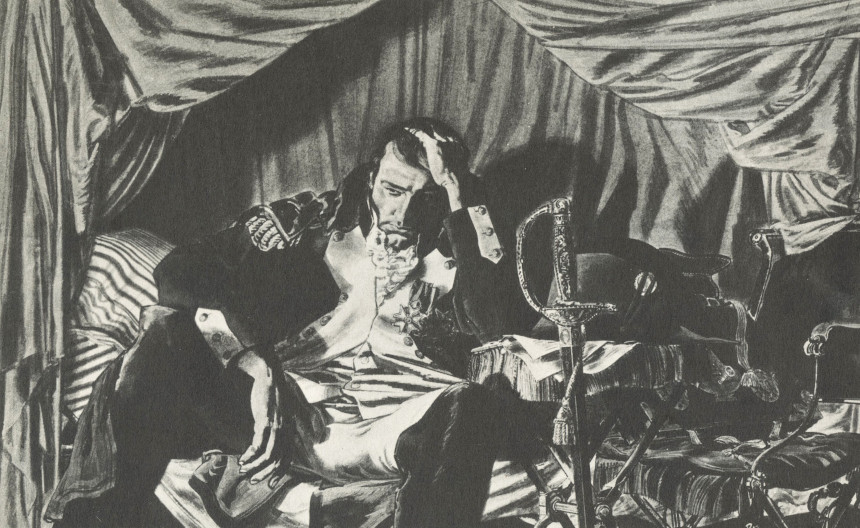

On one occasion, a client instructed Fawcett to revise the face on an illustration of Napoleon. Fawcett refused. He felt the client’s bad idea would diminish his picture, so he kept the picture for himself.

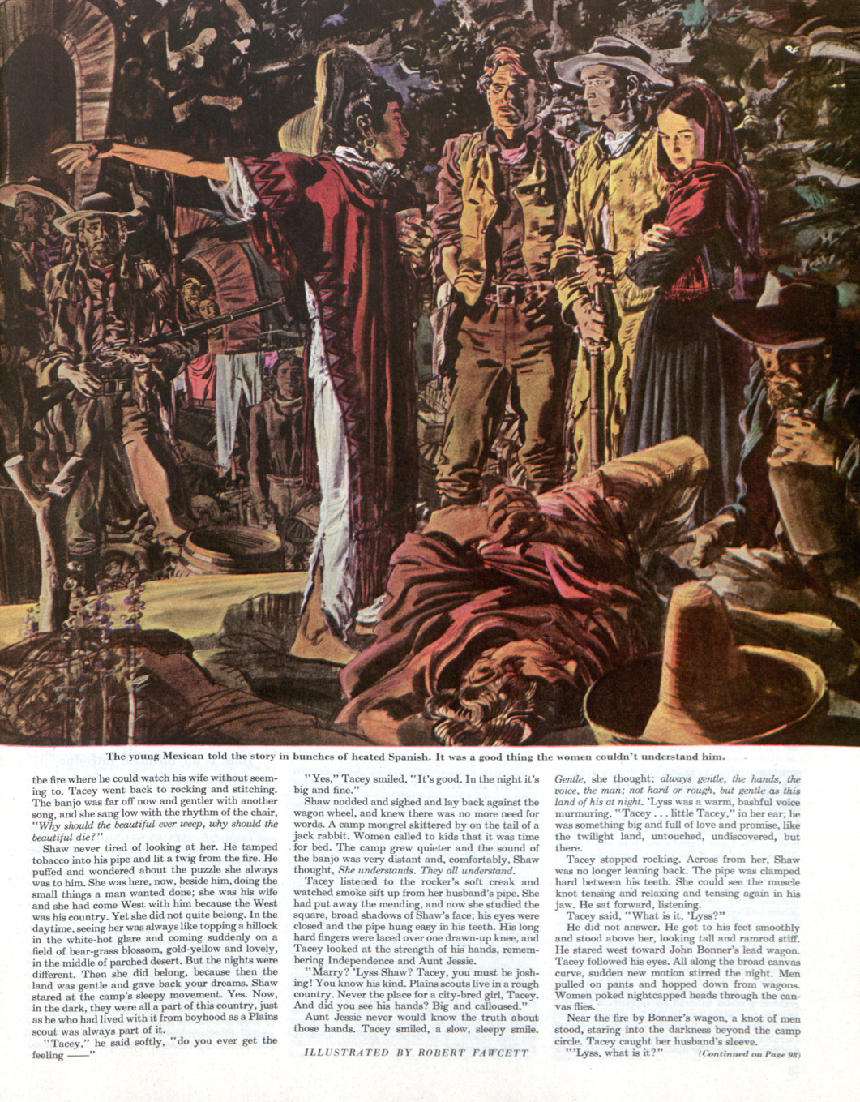

On another occasion, Fawcett turned down a plum assignment to illustrate the hit musical Oklahoma! Fawcett made preliminary sketches, but an art director suggested that Fawcett could improve the image by making the illustration more “theatrical,” putting bright colored shirts on the cowboys and making them more flamboyant. Fawcett replied that he was not interested in working in that style, and suggested that another illustrator would be better suited for the job. He returned the project to the client.

Fawcett would scold politicians, advertisers, publishers, and artists for their low standards or ignorant views. A less talented artist never could have gotten away with such behavior, but everyone had such respect for Fawcett that he never lacked for friends or assignments.

Fawcett was born in 1903. As a boy, he loved to draw and trained in lithography shops, advertising agencies, and commercial art studios — wherever he could find work. His dream was to attend London’s Slade School of Art, which was famous for training several generations of the best draftsmen in England. The school prided itself on stripping away all gimmicks and artifice and focusing on pure drawing skills — exactly what Fawcett wanted.

By the time he was 19, Fawcett had saved enough to pay for two years at Slade. He studied there from 1922 to 1924 and got a tough, old fashioned art education. Fawcett recalled that under the watchful eye of stern teachers, “I did nothing but draw from the model eight hours a day for two years.”

Fawcett returned to the U.S. and began his career as an illustrator. In an era when the popular illustration style was to paint in bright colors, Fawcett — who was color blind — developed his own distinctive methods. He would draw a picture in black ink, and then paint over it with washes of color, which he often had to select by reading the label on the paint tube.

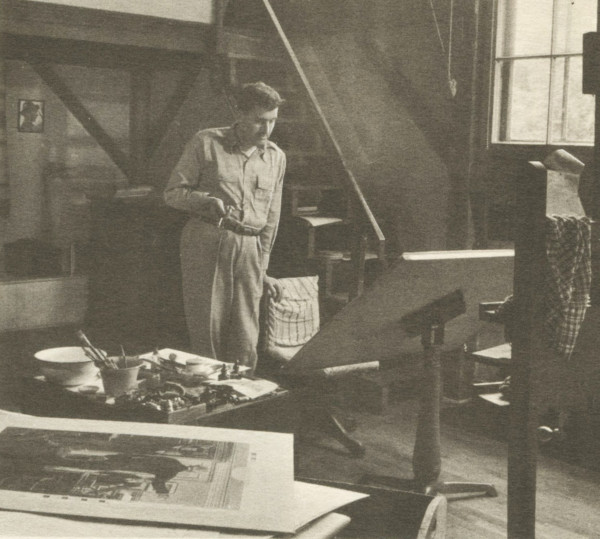

He soon became famous for his eccentric working habits.

Art Director Howard Munce described Fawcett’s technique for creating his own drawing tools: “Bob had a habit of poking around the studios of his friends and finding beat-up brushes that had known better days. The owner was always amused and pleased to give them to him when he showed an interest. Back in his own studio, he’d give the tired discards a shave and a haircut with a sharp blade and refashion them to suit his needs. Mostly he made wedged tips of various angles to serve special functions in his illustrations. In his hand, an old brush would begin a new life. He might use it to stroke in lines, to indicate a complicated bit of rococo molding, or to scumble in a particular texture. But however he used it, it would always leave his unmistakable imprint.”

Similarly, when magic markers were invented Fawcett was among the first professional artists to use them. Most illustrators stayed far away from the strange new medium because they were unpredictable and frustrating. Fawcett seized upon them and converted them into his own customized tools. He would whittle and reshape the felt nibs, or deliberately let them dry out to create a rougher line. He showed how to use the new tools to maximum advantage. The manufacturer of the new pens, Flo-Master, was so delighted when it saw how Fawcett was able to make use of their product that they sent him a lifetime supply. Knowing Fawcett’s reputation for high standards, they made an ad bragging that Fawcett used their markers.

In 1945, Fawcett’s career took a big leap forward when he received his first assignment for the Post, a serial entitled, “Cadmus Henry and the Hand of God.” This initial project was so well received that Fawcett was asked to be a regular contributor and soon graduated to the top of the Post’s pay scale.

A few weeks after his illustrations appeared in the Post, Fawcett was invited to lecture to students at the Society of Illustrators in New York. Fawcett was skeptical. “I’m willing, he responded, “but who wants to hear me?” When word spread that Fawcett was going to speak, the leading illustrators of the day flocked to the hall and crowded out the students. The event became standing room only, with established artists overflowing into the corridor and out the door, straining to hear what Fawcett had to say. He had arrived.

Fawcett’s success didn’t cause him to soften his views one bit. In interviews and in published essays he openly criticized the bad taste of the advertisers who paid for his work and the magazines who published it. In The Annual of American Illustration from the Society of Illustrators (1961), he wrote, “[T]he advertising and publishing fraternities pander to the lowest common denominator or make obeisance to expediency for temporary profit. [These people] will stand revealed in their mediocrity if it continues.” Fawcett said that illustrators needed to play a role in educating the artistic taste of the public, “showing [advertisers and publishers] who now stand as arbiters of the public taste just what that taste can be developed to accept.”

In an interview in American Artist magazine Fawcett acknowledged that illustrators faced powerful pressures to lower their standards. This was primarily because of “the intrusion of the man who pays the bills — the client. His position gives him the right to prefer and to buy mediocre illustration…and he exercises this right with almost unfailing regularity….The artist must know and accept this situation…where a large income is the prime motive.”

But he exhorted his fellow illustrators not to let income be their prime motive: “It should be the aim of every illustrator to withstand the tendency of publications to force his work into a mold, to make him conform to an accepted pattern. This is a difficult thing to do — the financial rewards of conforming are great…. We must be ready to refuse work unless it allows us to conform in some degree to standards that we ourselves set, and the result should add life and character to the printed page….”

When it came to politics, Fawcett was a flaming liberal. He would sometimes start his day writing angry letters to politicians or newspapers, fuming about some social injustice or other. He made his opinions known about schools, zoning, and community affairs. He rejected both the Republican and the Democratic parties because “prejudice, bigotry and fear in the U.S. are not the characteristics of only one party.” He was a lively conversationalist and loved to debate current events, but the wealthiest man in town stopped inviting him over for dinner when Fawcett predicted that his host’s mansion was going to be converted into a retirement home for workers.

Fawcett was not an easy man to live with, but for those who were strong enough to cope he proved a scintillating companion. He lacked much formal education, but his house was a center of cultural activity. He had a strong interest in music and became friends with world famous musicians including Arturo Toscanini and Jascha Heifetz, who visited him at his home. He related music to the abstract designs that were the foundation of his “realistic” pictures. He studied Beethoven’s notebooks and believed that Beethoven’s thematic notations were very similar to an artist’s conceptual sketches: they are both “notations of plastic linear ideas.” Fawcett said that abstract drawing “is probably as close to music as drawing can come.” He claimed that the greatest influence on his illustrations came not from the visual arts but from opera.

Fawcett also kept company with a wide variety of modern artists, such as the English sculptor Jacob Epstein. Original drawings by the abstract sculptor Henry Moore and another friend, the modernist painter Graham Sutherland, hung on his walls. He was also highly regarded by his fellow illustrators even when they didn’t socialize with him. When Fawcett wrote a book about his theories of drawing, Norman Rockwell called it a “great contribution to art as well as illustration.”

Fawcett never became as famous as Rockwell or other well-known illustrators of his day, but that was Fawcett’s peculiar trade off. He believed that an illustrator who wanted to protect his or her abilities had to be prepared to give up some profitable assignments if necessary, and to sacrifice part of his or her popular audience. And if you had to insult a few clients along the way? Well, apparently that was just a bonus.

Featured image: Robert Fawcett / © SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I was just wondering about your column the other day, David. And here you are with a brand new one on a true rebel with a cause. You know, I like the face on the Napoleon too, and would have kept it also. Who knows, he may have even said “Don’t you DARE judge me!” here, and on other occasions mentioned in the feature, from the sound of things.

The illustration of ‘Oklahoma!’ was indeed a plum assignment that would have paid a pretty penny, but Robert stuck with his principles. Though I don’t have a picture to compare, I’m not sure brighter, more flamboyant. ‘theatrical’ cowboy shirts would have been a good idea either.

I admire how he put himself through art school in London, his creative use of recycling worn objects for new uses, and how he embraced the magic marker. I know I’ve always loved it myself!

His remarks in 1961 were bold particularly because artists and illustrators (for both editorial and advertising) were increasingly facing the looming dark shadows of photography replacement on both fronts. Interesting too, about his inspiration coming from opera, and not the visual arts. The last paragraph speaks volumes also. I have a feeling Bob Fawcett has probably had to throw a drink in someone’s face a time or two when backed up against a wall. It’s not pleasant, but some unpleasant, rude people in business unfortunately make it an occasional necessity. .