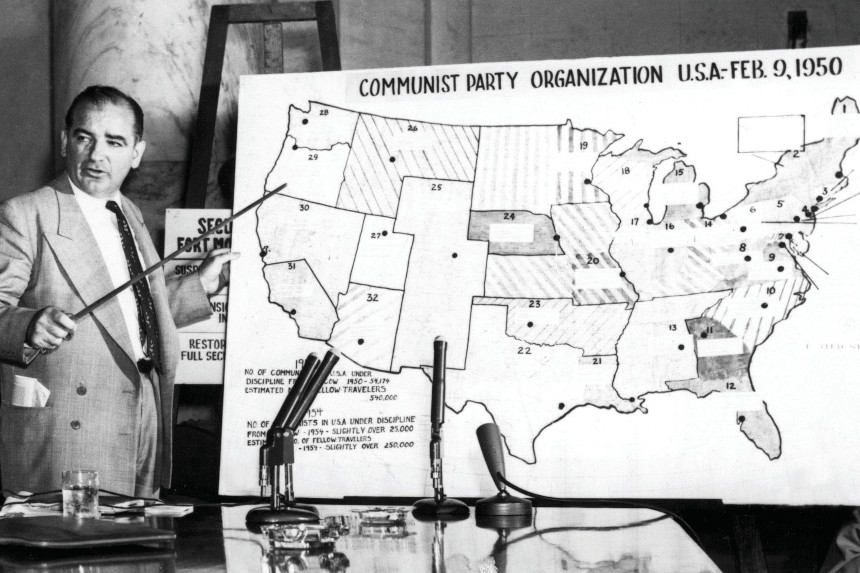

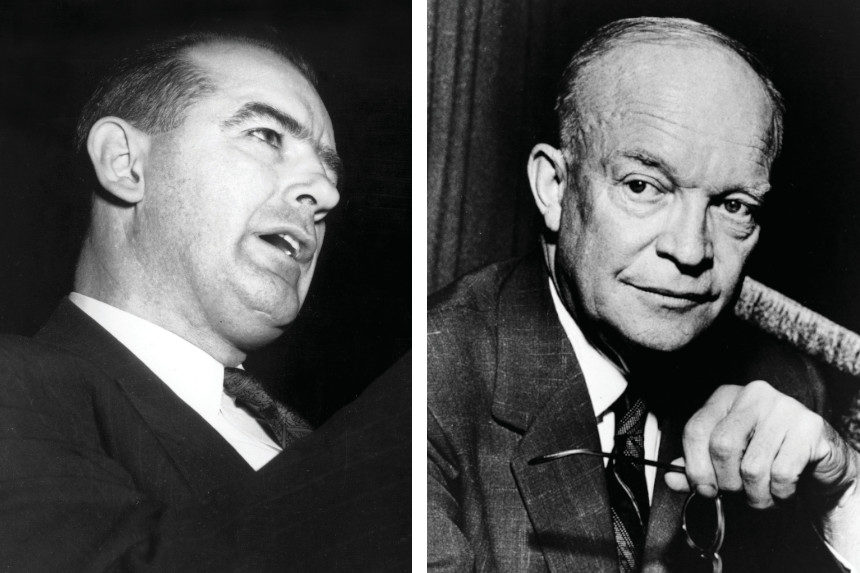

Dwight David Eisenhower was a man of inscrutable contradictions. Our 34th president loved Shakespeare almost as much as he did cowboy novels, and he listened to Beethoven’s “Minuet No. 2” right along with the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” At the beginning of his presidency, this avatar of the armed services threatened a nuclear strike against North Korea, although by the end he was sounding alarms about the “disastrous rise” of America’s military-industrial complex. Nowhere were those dueling natures more apparent than in his mercurial and at times mystifying approach to the subject of Senator Joe McCarthy.

While Ike told his family and friends that he detested McCarthy and all that he stood for, he vacillated between strategic retreat and frontal assault, seeming uncertain, for once, about the wisest combat strategy. It wasn’t easy for a professional soldier, much less a venerated five-star general, to wage peace. At times, he tried a middle course of behind-the-scenes obstruction. But during the critical first year of his administration, when the Wisconsin senator was at his reckless worst, President Eisenhower pursued a policy of appeasement that infuriated McCarthy haters as much as it delighted the senator himself.

Milton Eisenhower, Dwight’s younger brother and closest confidant, saw up close how McCarthyism and McCarthy bedeviled the commander-in-chief. On the one hand, the president “loathed McCarthy as much as any human being could possibly loathe another, and he didn’t hate many people,” Milton said. On the other hand, his brother knew that hating only had value if acted upon. “I wanted the president, in the strongest possible language, to repudiate him,” said Milton, to “tear McCarthy to pieces.”

Arthur Eisenhower, the oldest sibling and a sober-minded banker, also pushed Little Ike to take on the Wisconsin senator, whom he called “the most dangerous menace to America.” “I think of McCarthy, I automatically think of Hitler,” added Arthur, knowing there was no specter more likely to rouse the former Allied supreme commander to action than that of the Nazi murderer he’d vanquished a decade earlier.

While President Eisenhower listened, he didn’t act. His presidential papers make clear that he was privately fuming at McCarthy, who had vilified his mentor, General George Marshall. But Ike, cautious by instinct and patient by habit, lectured his brothers and his aides that to McCarthy, there was no such thing as bad publicity. Confronting him head-on would just guarantee him more of the spotlight and could make him a martyr. “I developed a practice which, so far as I know, I have never violated,” the president explained in a 1954 letter to a friend. “That practice is to avoid public mention of any name unless it can be done with favorable intent and connotation; reserve all criticism for the private conference; speak only good in public. This is not namby-pamby. It certainly is not Pollyanna-ish. It is just sheer common sense. … The people who want me to stand up and publicly label McCarthy with derogatory titles are the most mistaken people that are dealing with this whole problem, even though in many instances they happen to be my warm friends.”

On another occasion, the warrior-turned-politician confided, “That damn fool Truman created that monster. [McCarthy] didn’t exist until Truman went eyeball-to-eyeball with him. Whenever a president does that with any individual he raises that individual to the president’s level, and Truman was too stupid to understand that.”

So instead, Eisenhower waited, the way he had with D-Day and other great battles during the war in Europe, convinced that McCarthy would do himself in. Ike offered occasional critiques, along with a muted counterpoint to Joe’s raging bravado. “I was raised in a little town of which most of you have never heard. But in the West it is a famous place. It is called Abilene, Kansas,” he said in one of his veiled commentaries, broadcast over national radio and television in November 1953 and, as was his way, not naming the bullying senator. “That town had a code, and I was raised as a boy to prize that code. It was this: Meet anyone face to face with whom you disagree. You could not sneak up on him from behind, or do any damage to him, without suffering the penalty of an outraged citizenry. If you met him face to face and took the same risk he did, you could get away with almost anything, as long as the bullet was in the front.”

Takedowns like that were so veiled that much of America missed Ike’s point, and so tepid that Joe was undeterred. Mainly the president went on with his normal White House routine, while newspapers published so many photographs of Ike swinging golf clubs and casting fishing lines that the public sometimes wondered who was running the government. That uncertainty grew as reporters tried to parse his rambling, garbled answers at press conferences. Was he being rightfully circumspect or was he out of his depth? The verdict at the time was that his was a do-little presidency, a boring and safe aftermath to the wildly eventful Roosevelt and Truman tenures. Ho hum.

Eisenhower outdid Harry Truman in combing the government for security risks and trying to wrest from McCarthy the mantle of top-drawer commie-slayer.

Not so, a lineup of recent Eisenhower biographers tells us. Neither the peace nor the prosperity of the ’50s happened by chance, and the easygoing Ike was doing more than playing golf. His steadying hand was everywhere — ending the Korean War, preserving the New Deal, constructing a nationwide highway network, even taking on Jim Crow segregation by signing, in 1957, the first civil rights law since Reconstruction. The sly presidential fox was misleading Americans on purpose, projecting a grandfatherly calmness that bred public confidence and, not incidentally, helped him outmaneuver adversaries within his own political party. There was no clearer instance of that approach, the president’s defenders say, than his treatment of Senator McCarthy. The seasoned general’s willful silence was a calculated misdirection aimed at ensnaring the runaway senator. Eisenhower wisely “held his fire until McCarthy became open to attack by any right-thinking American,” said Princeton Professor Fred Greenstein, who came up with a name to celebrate that kind of governance by guile: The Hidden Hand.

The Hidden Hand is a convincing way to unravel the riddle of Eisenhower’s surprising successes building highways, expanding Social Security, increasing the minimum wage, and pushing forward on civil rights, but historians have been far too forgiving of the president when it comes to Senator McCarthy. For starters, Eisenhower did more than turn his other cheek. As far back as the 1952 campaign, he signaled his willingness to mollify McCarthy by dropping from a speech in Wisconsin his spirited defense of George Marshall, an about-face that Ike’s pal General Omar Bradley said “turned my stomach.” His aides claimed Eisenhower had to back off for electoral reasons, even though he was on his way to winning 39 of 48 states and would have won in a landslide even without McCarthy’s support or Wisconsin’s electoral votes. Eisenhower advisor and 1948 Republican presidential nominee Thomas Dewey had warned that McCarthy would become his “hair shirt” unless Ike hit him early and hard. Ike said he would, then didn’t. Syndicated columnist Drew Pearson sounded a similar alarm but said, “It was obvious from the questions [Eisenhower] asked that he just did not understand” why the columnist was cautioning him. Instead, according to Pearson, the candidate’s cowardly retrenchment on Marshall tipped off the Neanderthal wing of his party that they could “handle” him. Joe, too, smelled blood in the water.

Attack he did, from the instant Eisenhower moved into 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, with the White House failing to push back. That spring, the administration let McCarthy elbow his way into U.S. foreign policy after the senator unmasked the embarrassing fact that our closest allies were shipping goods to our Korean War enemies. In June, the president stood up to the senator over whether left-leaning tomes should be stripped from the shelves of U.S.-supported libraries around the world, but when McCarthy fired back, Eisenhower retreated. Ike stripped J. Robert Oppenheimer of his security clearance when McCarthy threatened to investigate the nuclear scientist and shunned Senator Margaret Chase Smith once she became Joe’s enemy. White House minions and even cabinet officers got the message. The secretary of state gave McCarthy the widest of berths and a say on security clearances; the attorney general brought no indictments in the wake of reports from two Senate committees lambasting McCarthy; and J. Edgar Hoover acted as though he worked for the senator instead of the attorney general and president.

Even more basic to McCarthy’s success, the president never challenged the senator’s meat-and-potatoes premises: that merely believing in communism was sufficient to pose a peril, and that Soviet subversion threatened the stability and safety of America. Determined not to repeat his predecessor’s presumed failure, Eisenhower even outdid Harry Truman in combing the government for security risks and trying to wrest from McCarthy the mantle of top-drawer commie-slayer. No matter that there were few if any real spies left by the time the general moved into the White House. The upshot was that the Red Scare dragged on longer than it had to. As for the constitutional protection that McCarthy undercut most often, President Eisenhower saw nothing wrong: “I must say I probably share the common reaction if a man has to go to the Fifth Amendment, there must be something he doesn’t want to tell us.” It was more delicate than Joe’s branding witnesses Fifth Amendment Communists, but just barely.

This ranking officer had never liked to wage war unless he was certain he would win. But holding back until the senator self-destructed — which happened in 1954, during the famous Army-McCarthy hearings — meant that, in the meantime, the country would pay a searing toll. The White House stayed silent while McCarthy upended the career of Reed Harris of the International Information Administration and rattled the Harris family to the point that his wife Martha later killed herself. Similar fates befell scores of other federal officials. It was on Eisenhower’s watch and partly thanks to his coattails that McCarthy was elected to an office that allowed him to chair the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, where he was able to wreak such havoc.

What could and should this president — the second in a row to be stymied by the rabble-rouser from Wisconsin — have done differently?

He ought to have ordered his FBI to plug its leaks to McCarthy, the State Department to stop cowering and backpedaling, and the International Information Agency not to “deshelve” its overseas libraries. Instead, said Martin Merson, who watched it all from a senior perch at the Information Agency, “the president made the mistake in those early days of not believing enough in the people, of feeling that he had to accommodate himself to the so-called practical politicians, to make compromises, to heed the cry of expediency.” But whereas Merson at least listened to the president’s justifications, McCarthy target James Wechsler offered this harsher verdict: McCarthy “was not superman; he was nourished more by the weakness of those who should have resolutely challenged him — most notably Dwight D. Eisenhower — than by any mysterious resources. There must have been many moments when he shook with laughter over the conduct of those he was harassing; surely he must have enjoyed Mr. Eisenhower’s austere refusal to ‘indulge in personalities,’ the craven formula devised early at the White House for the preservation of internal Republican peace and quiet.”

Ironically, the one area where pollsters said Americans doubted their commander-in-chief was his decisiveness — qualms that an iron-fisted response to McCarthy could have put to rest. “At a time when the public would doubtless have welcomed some kind of a statement on McCarthy by the president — either pro or con — he offered nothing,” said John Fenton, then the managing editor of the Gallup Poll. Drew Pearson still hoped he might, telling his diary in November 1953 that “it’s barely possible that Ike will now get off his fat fanny and realize that the chips are down, that he can’t temporize with a would-be dictator.”

Insiders were even more restless. At the same moment Pearson was venting in his journal, C.D. Jackson, Eisenhower’s special assistant on the Cold War, was penning a letter to White House Chief of Staff Sherman Adams. “Listening to Senator McCarthy last night was an exceptionally horrible experience, because it was in effect an open declaration of war on the Republican President of the United States by a Republican Senator,” Jackson wrote in response to McCarthy’s national TV and radio address, in which he charged that the Truman administration had “crawled with communists” and that the Eisenhower administration was only marginally better. “I hope,” Jackson added, “that this flagrant performance will at least serve to open the eyes of some of the president’s advisers who seem to think that the senator is really a good fellow at heart. They remind me of the people who kept saying for so many months that Mao Tse-Tung was just an agrarian reformer.”

At times Ike seemed aware of his own vacillating and doubtful of the Hidden-Hand strategy, as reflected in notes to himself and his counselors. “I continue to believe that the President of the United States cannot afford to name names in opposing procedures, practices, and methods in our government. This applies with special force when the individual concerned enjoys the immunity of a United States Senator,” he wrote in 1953 to a friend who chaired the board of General Mills. “I do not mean that there is no possibility that I shall ever change my mind on this point. I merely mean that as of this moment, I consider that the wisest course of action is to continue to pursue a steady, positive policy in foreign relations, in legal proceedings in cleaning out the insecure and the disloyal, and in all other areas where McCarthy seems to take such a specific and personal interest. My friends on the Hill tell me that of course, among other things, [McCarthy] wants to increase his appeal as an after-dinner speaker and so raise the fees that he charges.”

Other times, unable to tolerate the pain he felt biting his tongue regarding McCarthy, this thin-skinned president looked for scapegoats — Democrats, misguided staffers, or, in this case, the press. “No one has been more insistent and vociferous in urging me to challenge McCarthy than have the people who built him up, namely, writers, editors, and publishers. They have shown some of the earmarks of acting from a guilty conscience — after all, McCarthy and McCarthyism existed a long time before I came to Washington,” he wrote in March 1954 to another businessman-friend. “The area in which all of this really hurts is the adverse effect upon the enactment of the program of legislative action I have recommended. We have sideshows and freaks where we ought to be in the main tent with our attention on the chariot race.”

Two weeks later, in March 1954, he finally said he’d had enough and would tell the world how much he loathed the Wisconsin senator. It was liberating, as his press secretary, James Hagerty, reported in his notes on that day’s staff briefing, where McCarthy once again was topic number one. “I’ve made up my mind you can’t do business with Joe and to hell with any attempt to compromise,” Eisenhower told his assembled aides, not recognizing that he was echoing the sentiments of the predecessor he scorned, Harry Truman. Walking away with Hagerty, Ike added: “Jim. Listen. I’m not going to compromise my ideals and personal beliefs for a few stinking votes. To hell with it.”

At a press conference later that morning the president was asked whether Joe had the right to cross-examine witnesses in hearings called to investigate his own allegedly improper encounters with the U.S. Army. “In America,” Ike answered, “if a man is a party to a dispute, directly or indirectly, he does not sit in judgment on his own case.” It was the president’s most public and direct assault on McCarthy, but it was hardly the break that Ike had promised barely an hour before, or that Milton Eisenhower, C.D. Jackson, and others said was vital to curb a senator whom Jackson called “a killer abroad in the streets.”

The senator was ultimately brought down when the public saw at those Army-McCarthy hearings how reckless and ruthless he was, and to his credit, the president worked behind the scenes to ensure the Army stood fast against the demagogue from Wisconsin. In December 1954, the Senate found its own equivalently elusive backbone, condemning its colleague in a way that amounted to a political death sentence.

Looking back, it’s clear that Senator McCarthy’s reign of terror should never have lasted as long as it did. It’s also clear that President Eisenhower was the one national figure with the patriotic service and popular following who could have neutralized the out-of-control lawmaker. The president’s monthly approval numbers in 1953, at the height of McCarthy’s power, never dropped below 61 percent and topped out at 73 percent, the kind of fawning most leaders can only dream about and that McCarthy never even approached. In 1954, and in 12 of the 19 years between 1950 and 1968, Americans voted Eisenhower their favorite person in the world. And Ike, alone among Americans, had access to unvarnished reports from the FBI, CIA, and loyalty boards of every federal agency, laying out the limits of government treason and the breadth of McCarthy myth-making. He had the power and knew the lies.

But the most powerful general in America’s history, the supreme commander of an Allied force that crushed Adolf Hitler, shrank from confronting a drunken bully. At this milestone moment, rather than a Hidden Hand guiding the country, the Eisenhower waiting game looked more like an Empty Glove.

Larry Tye is the best-selling author of Bobby Kennedy and Satchel. Previously an award-winning reporter and national writer at the Boston Globe, he now runs the Boston-based Health Coverage Fellowship. For more, visit larrytye.com.

Excerpted from Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy by Larry Tye, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

An interesting take. Since I was not alive at this time my knowledge is only based upon what I’ve read. President Eisenhower was a paragon of virtue based upon what I have read and researched. McCarthy was an opportunist with a cause and communism was thought to be much more of a threat to America in the 1950’s then today. I can sympathize with the President in not wanting to give McCarthy a bigger stage by engaging him publicly . I’m sure McCarthy would have wanted that. In the end McCarthy is a footnote in history that many people either don’t know or have forgotten, while Eisenhower is remembered, loved and revered by many. I’m inclined to give the President more credit than the author of the piece is. In the end McCarthy flamed out, crashed and burned as the vast majority saw who he was. A thought provoking article nonetheless but I side more with the President in his low key handling of the situation rather than give McCarthy more limelight by engaging in a public shouting match.

It’s very difficult to know what IKE should have (or not) done as Mr. Tye’s article makes quite clear, in the handling of Senator McCarthy. He had a real dilemma on his hands with this man, to say the least. The solution appears simple, to have denounced McCarthy early on once he became President in 1953 and likely shut him down right quick.

IKE was a brilliant man both during during Word War II and as President, no question about it. I think Eisenhower believed McCarthy would wind up hanging himself by his own rope, which he did, only earlier. He did a lot of damage being out of control during the first half of the Fifties. I do wish IKE had neutralized Joe much earlier on before his own destruction in 1954. On the other hand, IKE let him burn himself which he knew he would. I’m sorry Joe took ‘prisoners’ with his outrageous witch hunts as collateral damage during his ‘reign’.

Eisenhower’s decision on what to do (or not) will likely remain controversial for years to come. I see both viewpoints on this, and would like to have gotten on TV to denounce McCarthy early on. It wasn’t that simple of course, and Eisenhower shrewdly did what he felt best in likely similar (enough) situations in World War II that worked, and applied it as President. I honestly can’t judge, but gave my viewpoint and thoughts here.