Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

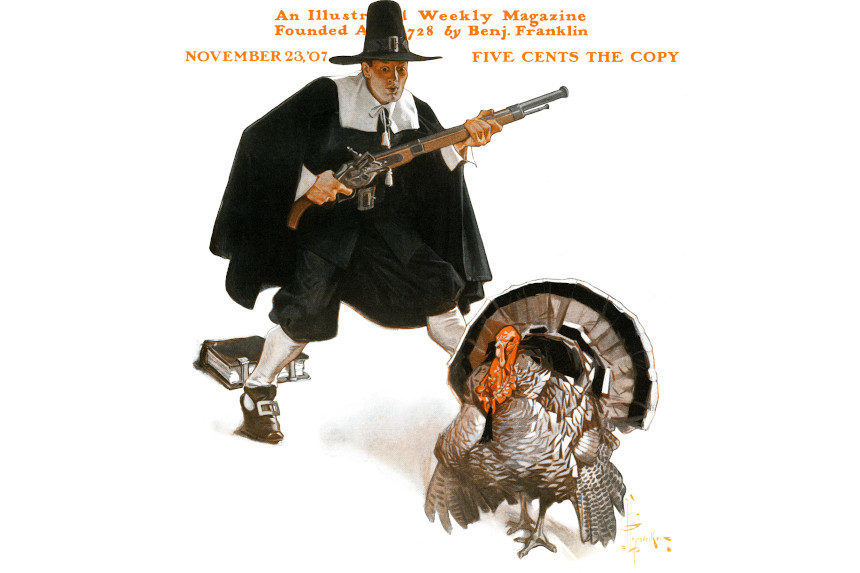

I was surprised to learn that the Plymouth Pilgrims — the ones who figure so heavily in the story of Thanksgiving in America — didn’t call themselves pilgrims when they set out across the Atlantic for the New World. It wasn’t until 1630, ten years after they arrived and nine years after the “first Thanksgiving,” that William Bradford, governor of the Plymouth Colony, used the term in writing to refer to the Mayflower colonists.

Then as now, a pilgrim denoted someone who traveled to a shrine or holy place as a devotee (or, as some sources have noted, as penance). The Plymouth Pilgrims came to the New World because they were fleeing religious persecution — not journeying to a holy place but from an unacceptable situation.

Etymologically, though, they could have considered themselves pilgrims from the get-go. That word pilgrim has a journey built into it, but it’s been obscured through alterations over the centuries. And though it might look like a word of deep-rooted English stock (grim has solid Germanic roots, but it’s etymologically unrelated), it might surprise you that pilgrim finds its roots where so many other of our words come from: Latin.

Latin had the two words per, meaning (among other senses) “through,” and ager, meaning “land, field” (the root of the word agriculture). These were combined into pereger, an adjective describing someone who traveled abroad, who went “through the land.” From pereger was derived an adverb, which led to a noun that originally meant “foreigner”: peregrinus.

All of this would have been second nature to, say, Julius Caesar. But when the early Christian church decided to make Latin its lingua franca, it made some changes. Peregrinus was employed as a name for believers who journeyed to places of religious significance, and their voyages were called a peregrinatio.

I know what you’re thinking: Apart from the p and the gr, peregrinus and pilgrim don’t have a lot in common. But something happened to these words over time. In Late Latin (around the 5th century A.D., give or take), peregrinus was altered to pelegrinus through a process known in linguistics as dissimilation (not to be confused with dissimulation, which is a type of deception). Dissimilation occurs when two identical or similar sounds in a word are pronounced in different ways so that they are easier to say or perceive. The world marble, for example, comes from dissimilation of the Old French marbre.

And now you start to see pilgrim taking shape. In Old French, the noun became peligrin, which English adopted around 1200 as pelegrim or pilegrim. Remember, there was no standardized spelling back then; even five centuries later, William Bradford called his group pilgrimes. But eventually, we ended up with pilgrims.

While you were reading about this lexical evolution, you likely came up with some other words that maybe you didn’t know were etymologically related to pilgrim. Just to sate your curiosity (and mine), here are two of them:

The peregrine falcon. This name, which arrived in English around 1550, is an anglicization of the Latin falco peregrinus, which had already been around for more than 300 years. It’s believed this name was chosen because peregrine falcons lay their eggs on inaccessible ledges and indentations in cliffs. In order to be captured, young peregrine falcons had to be taken while they were flying (i.e., making a pilgrimage) to their breeding place.

Peregrinations. Peregrinate is just a fancy word for “travel,” especially by foot, and one’s peregrinations are simply one’s travels. The word often carries a connotation of directionless wandering (especially when used metaphorically) more than a direct, point-to-point trek, but not always.

Want to fill up on more Thanksgiving word stories? “A Tale of Two Turkeys” explains how one word came to name both a delicious, ugly-headed bird and a Middle Eastern country (it’s not random coincidence), and “Cornucopia: A Thanksgiving Symbol that Predates America” explores the ancient history of the horn of plenty.

Featured image: © SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a pretty fascinating feature as to the origins of the word pilgrim. There were a lot of forerunner words (as is so often the case) before the word was finally settled on. The peregrine falcon and peregrinations are interesting to me too. When I was a kid, my Mom had a Ford Falcon station wagon, but it was never directionless; especially in the summer! I loved the swimming pool (still do) and we’d be at that big Van Nuys-Sherman Oaks Olympic-sized pool nearly every day once upon a time.