This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As 2021 gets underway, 2020’s debate over Confederate names and monuments continues to unfold. In his December 23rd veto message for the National Defense Authorization Act, President Trump noted that the bill’s provision for renaming military bases was one source of his decision to veto it: “I have been clear in my opposition to politically motivated attempts like this to wash away history,” Trump wrote. A week later, South Carolina’s Attorney General Alan Wilson filed a lawsuit arguing that the state’s Heritage Act, passed in 2000 to protect Confederate monuments from removal, was unconstitutional and should be overturned, the latest step in the state’s debates over its public expressions of the Confederacy.

These actions reflect the tangled political and legal layers to the debate over Confederate memory in America. But I believe they are also part of a far more overarching pair of interconnected questions about American history and identity: what and how we collectively remember of our past. While we have begun finally to confront the overtly racist images presented by these Confederate memorials, our larger national narratives remain both far too simplified and far too white. The most prominent sites of collective memory remain entirely dominated by a small subset of historical figures and communities. Take for example our currency, which features a collection of famous white men (both presidents and otherwise); the idea of replacing even the most overtly objectionable of those men, Andrew Jackson, with an inspiring individual woman of color, Harriet Tubman, was met with extensive controversy and has at this point been put on hold for nearly a decade.

These historical figures are indeed part of our past and our national identity. But if we continue to simplify American history as presented in our public spaces and our history textbooks into a mythic story dominated by a few (almost all white) individuals, we leave out not just countless other inspiring individuals like Tubman, but also the diverse communities whose contributions have truly shaped our nation at every stage. Perhaps this should be the year that we genuinely, accurately, and powerfully expand our collective memories to include them.

When it comes to those still-ubiquitous Confederate memorials, there’s a particularly straightforward way to expand the narrative: better remembering the conflicted post-war Reconstruction period. Those memorials were part of a century-long process of rehabilitating the role of the Confederacy that began immediately after the Civil War, with the Reconstruction-era efforts of white supremacist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan and their allies. For the last five years, Americans have largely failed to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Reconstruction (particularly compared to our commemorations of the Civil War Sesquicentennial), both because its events are far more difficult to simplify into mythic narratives and because they foreground African-American histories and figures. Fortunately, we’ve still got time to change that trend and better commemorate this historical anniversary, as Reconstruction continued through early 1877.

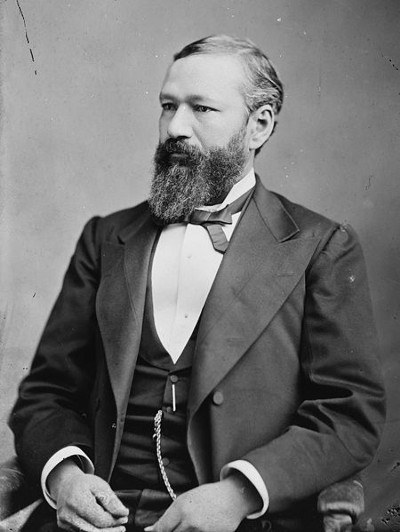

While Reconstruction featured such brutal histories as the Klan and its terrorist efforts, it also included far more inspiring American stories, including the first African-American officeholders in numerous political positions. 2021 marks the 150th anniversary of one profoundly important first: the ascension of P.B.S. Pinchback to the position of Louisiana lieutenant governor (and, the following year, to governor, becoming the first African-American governor of any state). Born in 1837 to a white slave-owner father and formerly enslaved African-American mother, Pinchback went on to serve as a captain in a Union army African-American regiment, and after the war attended the pivotal 1867-8 Louisiana constitutional convention. After his time in politics he co-founded New Orleans’ first historically black public college, Southern University, and later joined the 1890s Citizens’ Committee that brought Homer Plessy’s case before the Supreme Court. Pinchback is precisely the sort of far-too-forgotten late 19th century figure who deserves to be memorialized.

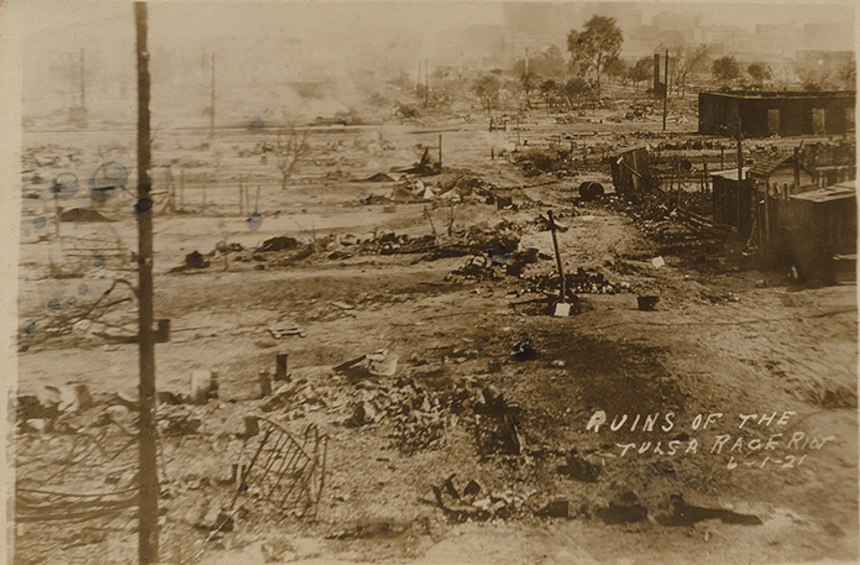

That 1867-8 Louisiana constitutional convention followed an 1866 convention in New Orleans that included one of the first post-Civil War massacres of African Americans and their allies. Such massacres were all too common throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of one of the most horrific: the May 30-June 1, 1921 massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Thanks in part to the efforts of countless historians and journalists and in part to a bravura opening sequence in the 2019 HBO series Watchmen, the Tulsa massacre has begun to enter our collective consciousness. But too often events like Tulsa are seen as singular, as illustrated by our relative failure to commemorate the centennial of the year-long series of massacres known as the Red Summer of 1919. The Tulsa centennial offers us a chance to better remember that trend of white supremacist racial terrorism, from New Orleans to Tulsa and beyond.

Tulsa’s African-American community, the Greenwood neighborhood known as Black Wall Street, was defined by far more than simply the massacre, however, and the centennial likewise offers an opportunity to remember that groundbreaking community. That includes inspiring individuals such as entrepreneur O.W. Gurley, who bought the first plot of land and named the neighborhood after Greenwood, Mississippi; J.B. Stratford, an ex-slave from Kentucky turned lawyer and activist who built a hotel and consistently advocated for solidarity among Greenwood residents; and A.J. Smitherman, a publisher who founded the neighborhood’s newspaper the Tulsa Star and organized community resistance to white supremacist violence. Any of those individuals deserve their own monuments and memorials, but so too does the entire neighborhood, a turn-of-the-century community that directly challenges both the narratives at the heart of Confederate memory and the erasures that racial terrorism like the massacre sought to effect.

Yet the Greenwood neighborhood itself was part of a different process of erasure, one that requires its own place in history. Like much of Oklahoma after it was opened to settlement with the Land Rush of 1889, Greenwood was built on Indian Territory, land that had been promised to tribes at the end of the Trail of Tears but subsequently stolen from them once again. Moreover, some of the African Americans who settled Greenwood had themselves been enslaved by and then integrated into those Oklahoma tribes, reflecting yet another layer to these fraught and interconnected American histories that resulted in a groundbreaking July 2020 Supreme Court decision, among other evolving stories.

These multi-layered, often contradictory and always challenging American histories are far more difficult to remember, much less to commemorate, than the simplified myths often represented by our monuments. But that makes it all the more important that we do begin to better remember them, pushing back on those myths and seeking to past with more nuance, more accuracy, and more meaning. As the Saturday Evening Post celebrates its own 200th birthday, I resolve that in 2021 this column will be part of that complex and crucial project.

Featured image: Image of ruins from the Tulsa massacre (Wikimedia Commons/DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Remember history less we forget… and repeat the same mistakes!

George Washington Carver would look great on U.S. currency too.

Slavery was terrible shameful part of America’s history and still is in other countries, but not all, yet very few owned slave, most all white owners…but like you and so many others don’t say or mention the fact that one of the biggest buyer & sales of slaves was also black….in Louisiana their were few black slave owners with 200-300 slaves working the sugar cane fields….as I first stated slavery is horrible and terrible no matter who bought&sold them!!!! sincerity to you.. DW …PS. I am non white just a conservative person of “color that looks at all the facts of history, not just one narrative..just tell the whole truthful story..all races would benefit..your narative was only selective part of a history.. history should be told truthful with all the facts……