Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

Robert G. Harris wanted to be an illustrator so badly that he drove his motorcycle all the way from Kansas City to New York, hoping to find work with a magazine. On his journey he took a detour through monsters, ghouls and wild west gunfights. But ultimately his dream came true, and he ended up a prominent illustrator for The Saturday Evening Post. He even became friends with Norman Rockwell.

Harris was born in 1911 in Kansas City, Missouri, the son of a hat salesman. He showed artistic promise at an early age, so his parents enrolled him in art lessons at the Kansas City Art Institute. Harris did well, but he found Kansas too provincial and confining. So at age 21 he hopped on his motorcycle and left for the East Coast. He landed in the suburb of New Rochelle, where he was able to rent space with another young illustrator from Kansas City, John Falter.

Once in the New York area, Harris tracked down two of the most famous art teachers of the period, Harvey Dunn and George Bridgman. Dunn was a highly regarded illustrator for the Post and Bridgman was the art teacher of Norman Rockwell. Harris hoped he’d be able to follow in their footsteps and work for high class magazines.

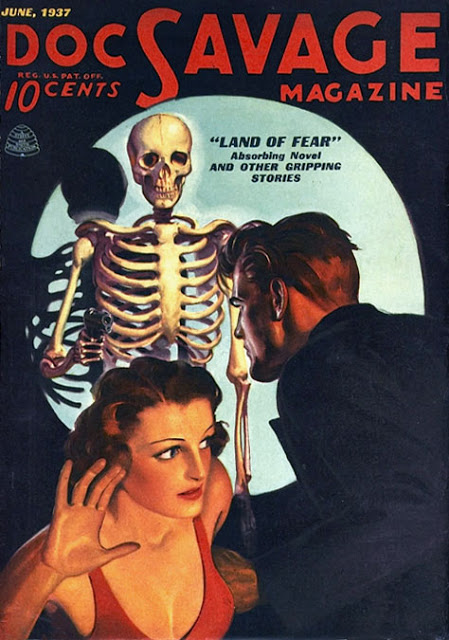

However, when Harris began to get assignments, it was not from the magazines he originally hoped for. In the 1930s the American magazine market was flooded with trashy “pulp” magazines, cheaply printed adventure stories about gunfights and zombies and aliens from outer space. Often their covers were lurid paintings featuring young women in peril. It was here that Harris first found employment. His zesty, imaginative paintings appeared regularly on the cover of pulp magazines such as Doc Savage, Thrilling Adventures, and Wild West Weekly.

Pulp magazines may have been on the outskirts of respectability, but with the income from his covers Harris could afford to get married and settle down. In 1935 he wed Marjorie Elenora King and began to raise a family.

Harris’s friend, famed illustrator Al Parker, chose to live in Westport, Connecticut for its “cornfields and crickets,” with no distractions from neighbors. Parker believed this was a good environment for creativity. He sold his paintings to magazine publishers headquartered in Manhattan but he preferred not to paint there.

This sounded like a sensible arrangement to Harris, so he moved to Westport as well. With his new income from pulp magazines, Harris was able to build a large home and studio with a three car garage. He even traded in his motorcycle for his own private sea-plane at the beach.

By the end of the 1930s, Harris was more than ready to trade his zombies and gangsters for assignments from higher quality “slick” magazines such as Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, Ladies Home Journal, McCall’s, Redbook, and ultimately, The Saturday Evening Post.

World War II helped with his professional transition. Harris took a break from pulp magazines as he volunteered to work for the USO to draw portraits of wounded servicemen in military hospitals. Harris worked in hospitals in New York, Connecticut, Virginia, and North Carolina.

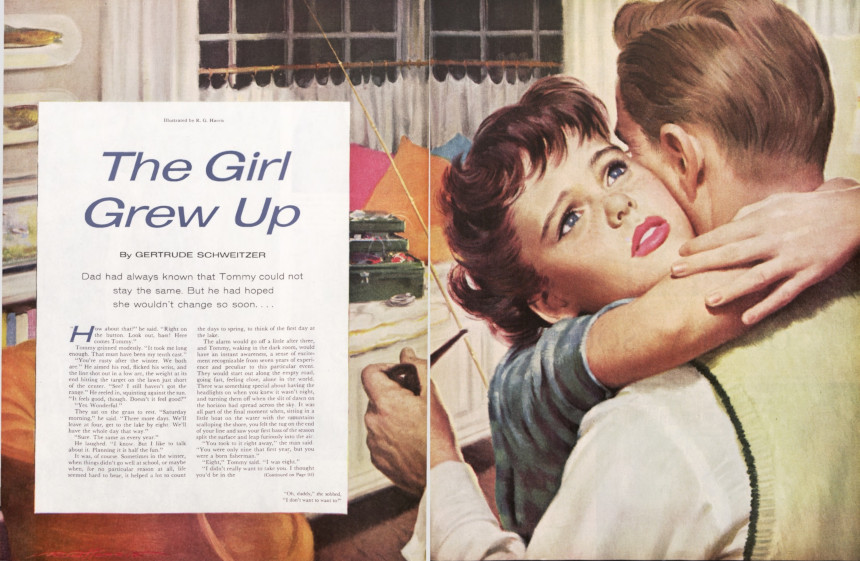

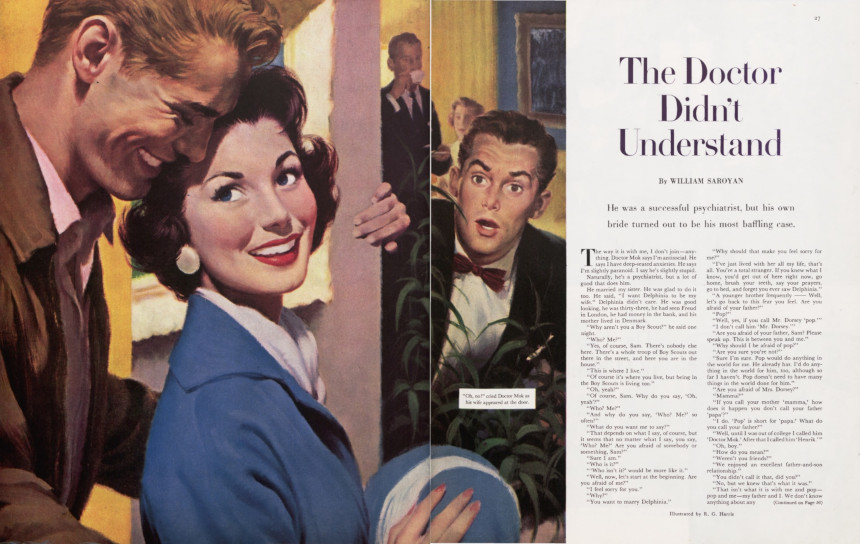

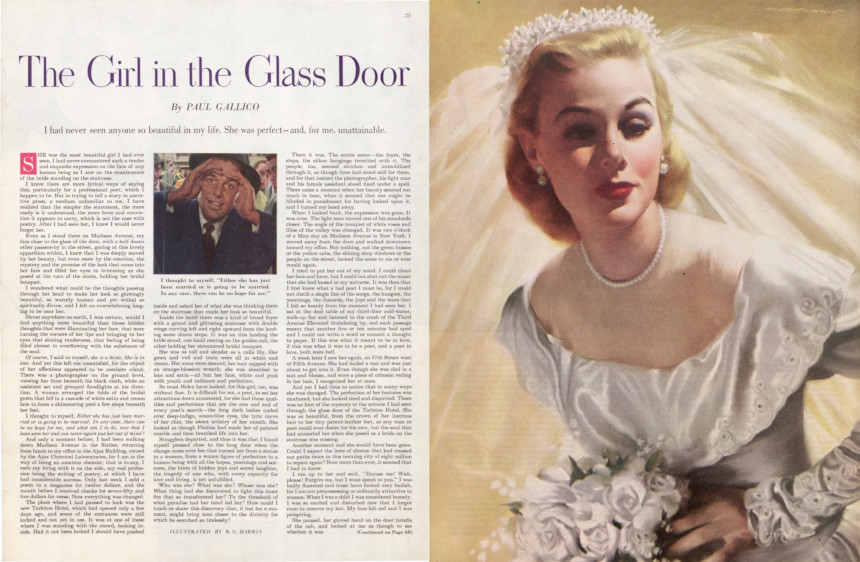

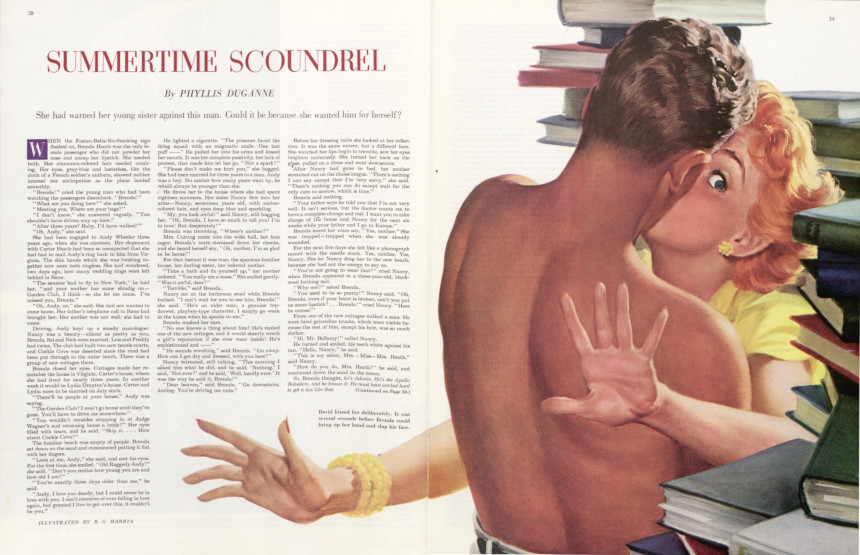

After the war, the market for illustration changed. Harris’s illustrations took on a much more genteel, domesticated tone.

Rather than painting gunfights at the O.K. Corral, he painted lovers’ quarrels between attractive young newlyweds.

Instead of imagining torture pits for his pulp magazine covers, Harris was able to use his own home as a backdrop for his illustrations for the Post.

These years were happy years for Harris, and his illustrations for the Post became extremely popular for their sunny, romantic tone.

Harris also painted advertising art for major corporations such as Coca-Cola and Cannon Sheets.

As the illustration field grew, top artists from around the country flocked to Westport, which became a mecca for great illustrators. They built houses with swimming pools and the community grew. In the 1950s the open fields began to fill with houses, and Harris found Westport was becoming too crowded for his taste. Illustrator Al Parker decided to abandon Westport for the wide-open spaces of Arizona. Not long after, Harris followed, bringing his wife and two children to Phoenix where he continued his illustration career.

He remarked that he had not been in Arizona since he roamed around as a young man on a motorcycle. He had used his memories of Arizona when he painted his wild west covers for pulp magazines, but he wasn’t painting that kind of subject matter anymore.

Now Harris was interested in a different subject matter and re-invented himself once again, painting portraits for well-to-do Arizonans. He continued a satisfying career as a portrait artist until his retirement in 1989.

If you’re interested in reading the short stories that Harris illustrated or want to browse more art, inspiring stories, fiction, and humor, subscribe to the magazine to see complete issues going back to 1821.

Featured image: Robert Harris / © SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for doing this wonderful feature on Robert Harris. I love his art style a lot, and am sure he much preferred doing such striking illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post than anything prior to that pinnacle. Still, Cosmopolitan (pre-1952) had some wonderful illustrated covers of beautiful women.

It’s hard to believe (now) that any of the other magazines you mentioned ever had beautiful covers or inside illustrations, but they did. He also did situational covers for Liberty starting in 1937. That opportunity likely opened due to the passing of their main cover illustrator, Leslie Thrasher, in late 1936. I don’t know if he ever did any covers for Collier’s like Jon Whitcomb.

I’d like to check out his pulp magazine art further. They likely were the more beautiful and classy covers of those magazines of otherwise ‘low degree’. (I can only theorize these magazines flourished in the 30’s as nice reading escapes from the Depression into other outer worlds entirely.)

Love the Post illustrations you chose here, David! Particularly the ones from 1950 and 1957. They’re extremely beautiful and border on photographic portraiture like many of Rockwell’s in the 50’s as well, but still retain the elements of fantasy actual photographs can’t quite capture.

No comments about Robert Harris would be complete without my mentioning his 1959 illustration for ‘The Cold War Blonde’, a gorgeous (and terrifying) ‘action/motion’ shocker hanging on one of my walls right now! When my cash flow improves once again, I’d love to buy those two if they’re available. There’s nothing quite like a little magical mid-century visual infusion every day, now more than ever!