Just four years ago, New Orleans was reckoning with its own history of insurrection.

After a city council vote, the city removed a conspicuous stone obelisk that had been erected to honor an 1874 armed rebellion against its own state. It was emblazoned with an egregious, racist message lamenting that the federal government had restored power to the elected Republican “usurpers” at the time but proudly claiming a later election “recognized white supremacy in the south and gave us our state.”

The monument to commemorate the so-called “Battle of Liberty Place” was completed in 1891, but the inscription to white supremacy wasn’t added until 40 years after that. In those years, New Orleanian ex-Confederates and white Democrats celebrated the insurrection annually with memorial ceremonies. The obelisk was a towering relic of the long-standing conviction that the insurrectionists had struggled nobly for the white race against a corrupt state government.

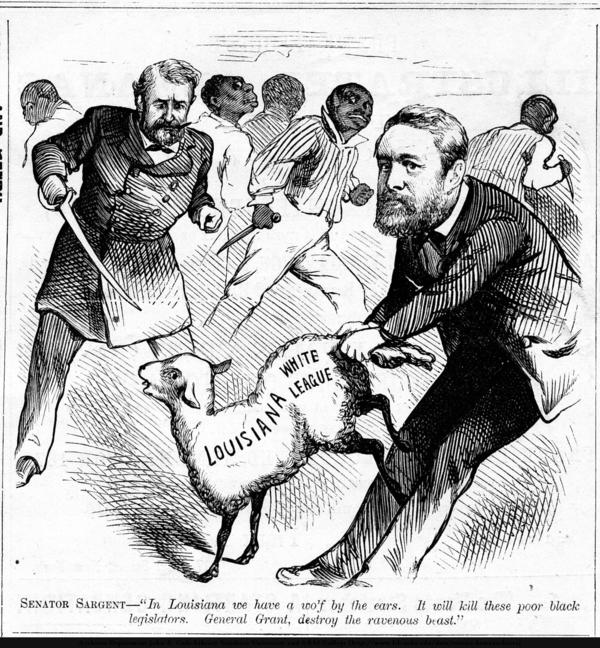

The group that took on Louisiana and almost won was a paramilitary cousin of the Ku Klux Klan called the White League. They had organized quickly into a dangerous and powerful force for white supremacy that forwent masks and hoods. Their 1874 rebellion was the culmination of years of racial and political terror in Louisiana and surrounding states, a resistance to Reconstruction that northern newspapers like the Cincinnati Gazette saw as “the old war in a new shape.”

The White League’s reign of terror over Black southerners after the Civil War was often euphemistically enshrined as various “battles” and “riots” for liberty, but stone monuments and revisionist Southern traditions obscured an uncomfortable history. The White League led an armed insurrection against their elected government for a single objective, according to their own platform: “to reestablish a white man’s government.” To accomplish this, they would necessarily have to dismiss the votes of newly-enfranchised Black voters.

“This is a part of American history that isn’t easy to face,” historian David Blight told PBS about the Reconstruction Era. “It tells us that we had a moment in our history when our politics broke down, our society broke down, our police power broke down; the government wasn’t functioning sufficiently enough to protect one group of citizens from another who simply engaged in wanton vigilante violence of the worst kind.”

New Orleans was a sort of staging area to resist Reconstruction and hold onto the Lost Cause partially because of its unique demographics, according to Lawrence Powell, Professor Emeritus of History at Tulane University. “It attracted a lot of Southern nationalists,” he says. “At the same time, you had a highly mobilized Black intelligentsia unlike any other in the country. This community of gens de couleur libres, arguably the most prosperous and cohesive free Black community in the country, engaged in a tradition of French republicanism … they had an idea of what freedom should look like, more than just at the ballot box, but dignity and equal standing in the public square.” He says this Black political coalition was responsible for ratifying the most progressive state constitution in the South, the Louisiana Constitution of 1868, which established racial equality in public education and voting rights and stripped away the oppressive “Black Codes.”

Mere legislative language — without enforcement — would prove insufficient to terminate a legacy of racial subordination.

Disaffected white Democrats and freedmen sparred intermittently in post-Civil War Louisiana, but the former mounted a massive escalation in Colfax — a town along the Red River — in 1873, when a white militia rode in and massacred dozens of Black Republicans defending their courthouse (sources claim between 70 and 300 casualties, only three of them white). Historian Eric Foner called the Colfax Massacre “the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era.” Though federal authorities arrested and tried the white militia members, none were convicted.

Federal intervention irked white Democrats, and the lack of consequences emboldened them. On April 17, 1874, the Opelousas Journal announced a public meeting “under the banner of the ‘White League,’” to unite white voters against the supposed threat that “negro voters” would “Africanize the State.” Other papers echoed calls for white political unity, even at the cost of bloodshed. In nearby Alexandria, ex-Confederates founded a paper called The Caucasian that stoked white voters’ fears of Black political dominance in its first issue: “the leading political principle of the negro is his unconquerable hatred of the white race.”

White Leagues quickly began appearing throughout Louisiana — particularly in parishes along the Red River — which were largely reorganized from the Democratic memberships of earlier incarnations of terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camellia. The Crescent City White League, of New Orleans, had only to change its name from the Democratic Crescent City Club. By June, The Opelousas Courier printed a notice: “From this date, the control of the editorial columns of the Courier passes into the hands of the White League.”

In their public pronouncements, Louisiana’s White Leagues mostly declared to be purely political organizations focused on democratic tactics, with occasional nods to the possibility of violence. But they did not only advocate for a “white man’s government;” they refused to accept otherwise. That summer, news of Louisiana’s new undisguised white supremacist militias flurried around the North. The Buffalo Morning Express predicted plainly, “The White League movement recently organized in Louisiana by the Democrats, means a war of races which shall end in the subjugation and disenfranchisement of the negro.” As the Chicago Tribune claimed, “The assertion of these leagues that they are peaceful in purpose is daily contradicted.” Louisiana was receiving national attention for the “race war” unfolding there with regular assassinations, massacres, and lynchings.

Albert H. Leonard, a Shreveport Times editor, power broker, and prominent White Leaguer, began calling on his fellow paramilitaries that summer of 1874 to murder Republican political leaders and instill fear in Black communities. In Caddo Parish, whites murdered 10 percent of all Black men there during Reconstruction. All throughout rural Louisiana, the White League would ride into town 1,000-strong and force local Republican officeholders to resign, often murdering them anyway.

They held that uneducated Black voters were being swindled by the Republican “carpetbaggers” from the North. Ricky Sherrod writes of the so-called carpetbaggers in Louisiana History, “If few of these men were saints, neither were they the stereotypical, lowbred soldiers of fortune or opportunistic and greedy northern parasites bent on unrelenting exploitation of vulnerable southern communities.” Most historians agree that Republican politicians in the South during Reconstruction were certainly no more corrupt than the Democrats who came before and after them.

The White League also systematically handed elections to Democratic candidates by silencing and intimidating Republicans and Black voters. In nearly every parish in the state, instances of egregious voter intimidation and fraud were documented in a Congressional Committee report, Condition of Affairs in the South in 1875. In Rapides Parish, the White League “forced the opposition candidates from the stand with bowie-knives and revolvers, and would not allow them to address the people.” In others, they stole ballot boxes, coerced Republicans from running, and whipped and murdered anyone registering Black voters.

Historian Powell says that what gave the White League momentum was “the visible, unmistakable retreat from Reconstruction on the part of the federal government and judiciary. These guys were reading the tea leaves of national politics, and drawing the right conclusion that they were giving up.”

In August 1874, members of the White League rode first through Natchitoches and then into Coushatta, in Red River Parish, and deposed and murdered 10 Republicans (four Black and six white), in what was remembered as the Coushatta Massacre. The brazen murder of white officials shocked many in the state who hadn’t been attuned to the White League’s steady takeover of Louisiana. By this point they had taken local government by force in much of the state. Earlier that month, former Confederate general Fred Ogden — leader of New Orleans’ Crescent City White League — wrote a letter to a comrade in Vicksburg, Mississippi, congratulating them on “the splendid victory so manfully obtained by your people at the election.” In Vicksburg, their own White League members had patrolled the streets, intimidating Black people there away from the polls, and the Democrats handily won. “New Orleans will take care to emulate the spirited example of Vicksburgh [sic],” Ogden wrote.

In fact, Ogden’s White League would set its own example. After capturing the better part of the state to scarce federal resistance, the White League set its sights on a wholesale siege of the state government in New Orleans.

The Battle of September 14th (later the Battle of Liberty Place) was, as G. Howard Hunter writes in Louisiana History, “planned in the cloakrooms of the Pickwick and Boston clubs” by New Orleans elites. Powell calls it a strain of “silk stocking vigilantilism.” He says, “the people who manned the Crescent City White League came from — let’s put it this way — the Garden District.” The well-to-do White Leaguers had been organizing their ranks since summer with the promise they could avenge their political misfortunes.

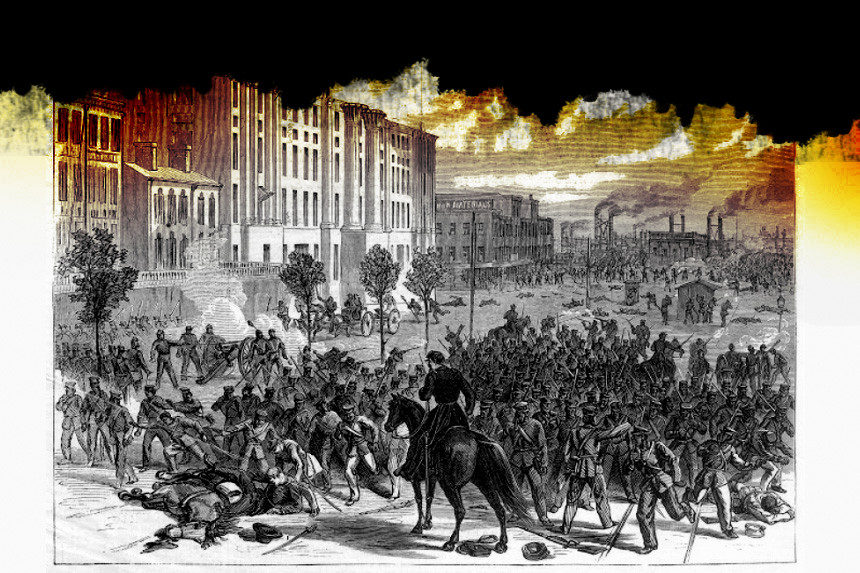

On the night of September 13th, the White League distributed flyers announcing a mass meeting at Royal and Canal streets the next day. Thousands showed up to demand Republican Governor William Kellogg’s resignation. Around 3 p.m., Ogden led his army of White Leaguers down Poydras Street. He had around 2,400 White League men, but they were joined by around 8,000 more who had answered a last-minute call for reinforcements from D.B. Penn, the 1872 Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor who hoped to take power.

The White League army marched to Canal Street, where they were confronted by General James Longstreet’s integrated militia and the Metropolitan Police, a force altogether only a fraction of the size of the League. Unlike most other instances of Reconstruction violence, this resembled a formal battle. While Governor Kellogg hid out in the Custom House — a federal property the League would not breach — the city’s police force was swiftly defeated. As the size and formidability of Ogden’s army became clearer, the Metropolitan Police and Longstreet’s militia scattered and returned to their homes. The next day, the Daily Picayune reported 12 dead from the “Citizen’s Party” and 30 dead policemen (other sources have reported fewer deaths). “So ends the Kellogg regime,” they reported. “Its boasted armament dissolved before the furious rush of our citizens.”

The White League declared Penn the acting governor of Louisiana, and he sent a telegram notifying President Grant that evening. According to Joe Gray Taylor in Louisiana History, it was “probably the largest military insurrection that has ever occurred against the government of a state of the United States.”

Within three days, Penn and the White League surrendered power back to Kellogg as the city came under military occupation by the federal government. The Picayune echoed Penn’s language about the “usurpers” being restored to power, sneering at the “army of carpet-baggers and state officials now being vomited forth by the opening doors of the custom-house.” The reference to Louisiana’s Republican officials as “usurpers” would eventually make its way onto the stone monument at Canal Street.

“The Battle of Liberty Place,” as it came to be known, was a key event in the curated mythos of Confederate valiancy in New Orleans. “This was probably the most politicized memory of the state’s history,” Powell says, “and they would use it to galvanize young men to arm and march on the polls … They had these ceremonies every year on Sept 14th. It was their Bunker Hill.” Romanticized notions of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy were woven into Mardi Gras celebrations, and large statues for Confederate generals were erected. The White League’s insurrection would be celebrated annually by Confederate veterans and, later on, the Klan well into the 20th century, helping to keep alive “the myth of New Orleans as a Confederate bastion.”

Powell was an early advocate for removing the “Battle of Liberty Place” monument in New Orleans. “My feeling was that having that monument in the center of … a black-majority city offended the sensibilities of most of the people in the city because it was a monument to white supremacy,” he told a radio host after writing an article about the monument in 1990. He says that he received death threats for expressing such. Powell recalls, “I think I said they should throw it in the river, and that got me into hot water.”

At the time, former Klan leader and neo-Nazi David Duke was representing Powell’s district in the Louisiana House of Representatives, and Duke had popularized the monument as a rallying place for the KKK. Powell co-founded the Louisiana Coalition Against Racism and Nazism, a PAC, to expose Duke’s racist history.

Powell says the history of Louisiana’s 1874 insurrection largely vanished down the trapdoor of popular memory until the recent national conversation about race in national politics. “Reconstruction is the place you would turn to to discover why the warning signs are turning red,” he says, “and it all boils down to race … There’s a through-line, practically [to today’s politics]. It unfolded during a time of a permanent legitimacy crisis.” Democrats wouldn’t accept a Republican government under any circumstance, because they didn’t believe their voters were legitimate.

Powell has studied and written about this history for much of his career, and he says the persistent myths of the “Lost Cause” and the corruptness of carpetbaggers show that we still have yet to fully reckon with the violent white supremacy of the period. “Reconstruction has endless lessons to yield,” he says, “though I never thought in my lifetime I’d see them become relevant as they have today.”

Featured image: “Louisiana Outrages — Attack Upon the Police in the Streets of New Orleans,” Harper’s Weekly, October 3, 1874, The Historic New Orleans Collection

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Interesting how just the right timing of discussing history can become propaganda.

Thank you for writing this terrifying and unfortunately most timely (again) article. This is a shameful, horrifying reality of this country’s past and present. The insurrection of just 2 weeks ago at the nation’s Capitol serves as a lesson that must be heeded as the warning it is.

White supremacy racism is unfortunately all too alive and well, even if most Americans think of it as something of long ago. It isn’t, and must continually be squelched as to not take over. Our American history books have largely ‘white-washed’ this, along with other very unpleasant facts including but not limited to how Native Americans were (are still are) mistreated and victimized at the hands of whites.

We must be reminded of the ugly realities of racism, such as this, as it is always just under the surface. Even today’s American history books still try to make our history more palatable when it is not. The truth is we’re ashamed of our own history, for good reason. We’ve done wonderful things too, which should be celebrated, of course. We ARE a wonderful nation, but can never live up to our full potential until these problems are fully, honestly and finally addressed across the board. Inequality of all kinds; race, gender, economic and more. This must be an on-going process, just as the U.S. is a work in progress. That’s a good thing!

Let us all learn from what happened earlier this month that domestic terrorism from within remains as big a threat as that from which is not. What happened could not have without the consent, permission and encouragement from those within our own government. Those responsible must be exposed and punished for making such an atrocity and violation possible. It requires always having our guard up because the enemies from within are always lurking in the not-so-dark shadows of the American underbelly that just came perilously close to overthrowing our democracy.