When Harvey and Daeida Wilcox purchased 120 acres of farmland northwest of Los Angeles in 1886, they had plans to live a quiet life on their ranch that they called Hollywood. The prohibitionist couple’s dream of a fig farm faltered just one year after their purchase, and as a result they turned to an industry that had never failed them before — real estate. The Wilcoxes divided up their land and sold it off quickly to like-minded buyers, envisioning a sober and deeply religious community. Perhaps their dream of a Christian utopia could have come true had it not been for a clever man from New Jersey — Thomas Edison.

The predominant narrative regarding the rise of Hollywood was that land was cheap outside of Los Angeles, the weather was always pleasant, and labor was easy to find. All these factors that drew people to Hollywood are completely true; however, the major factor that pushed independent film makers out west was Edison’s cutthroat business style, which left film makers only one option: escape the reach of his grasp.

Edison’s take-no-prisoners business tactics often get outshined by his innumerable inventions and patents. His laundry list of inventions includes the light bulb, the phonograph, the alkaline storage battery, and the kinetograph — the first ever movie camera.

In his early years, Edison felt no loyalty to any client of his and made himself available to anyone who would pay him. One of the earliest examples of his business savviness involved the development of the quadruplex, a machine capable of transmitting four telegraph messages at the same time. The telegraph giant Western Union contracted him to develop the technology for their ever-growing service; however, Edison unceremoniously broke his agreement with Western Union in 1874, when finance magnate Jay Gould paid him over $100,000 for the invention. The under-the-table deal led to years of litigation, and eventually Western Union gained control of Edison’s device.

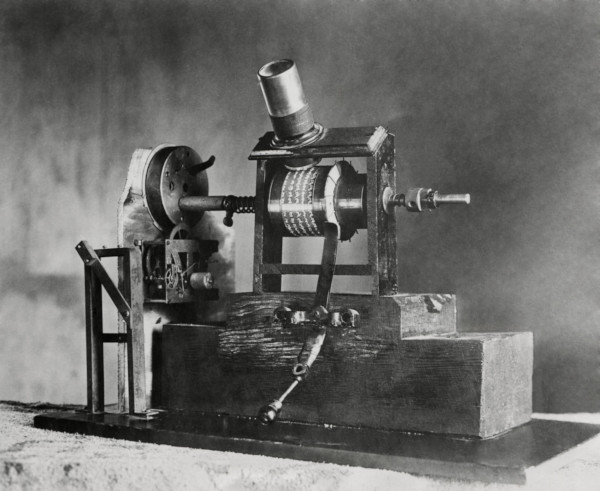

Although Edison himself patented the kinetoscope movie viewer in 1891, it was developed by one of his assistants, William Kennedy Dickson. Dickson and Edison invented what so many had tried before them: a moving picture. The invention was meant to help promote Edison’s phonograph, generating a larger use of the sound technology. However, the ability to synchronize sound to motion pictures was harder than expected. This led to the rise of the silent film. As a result of the invention of the kinetoscope movie projector and the kinetograph movie camera, Edison opened America’s first movie studio, Black Maria.

The founding of Black Maria made West Orange, New Jersey the unlikely film capital of the world. With Edison’s studio beginning to pump out the first silent movies in history, competition began to grow, causing him to react accordingly. Edison used what he is often most known for to deter competition and ensure that Black Maria maintained its supremacy — patents.

Edison formed an alliance among other major patent holders in the industry. It was known as the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC) or, more colloquially, the Edison Trust. The Trust included competing production company that Dickson founded, Biograph, which held its own camera patent; as well as Eastman Kodak, the biggest producer of raw film. Given how many patents the cartel covered, it was virtually impossible for any independent movie studio to make a film without being bombarded by copyright infringement lawsuits from the MPPS. Two hundred eighty-nine legal complaints were directed at Universal Studios alone. Any movie being made at the time had to go through Edison, making him the king of the movie industry.

Edison’s intimidation techniques even wandered outside the law on some occasions, according to Steven Bach’s book, Final Cut. The MPPC would hire mobsters to rough up film makers that were violating their patents.

The East Coast became suffocating for non-Edison-affiliated film makers. Every turn they made in the industry was met with a lawsuit, stifling creativity and stalling innovation. The environment that Edison concocted led to independent film makers wanting to get far away from him and his monopoly. Hollywood seemed like the ideal destination.

Out west, judges were much less tied up in Edison’s oppressive patent apparatus and were much more likely to rule with the independents than with the conglomerate. Even in instances where Southern California judges ruled with Edison, their rulings were hard to enforce given that cross-country travel was onerous and expensive.

Despite the more favorable courts, film makers were still under constant threat from Edison’s cartel. The ruling of United States v. Motion Picture Patents Co. in 1915 changed all this and provided the reprieve the industry had been seeking. The court struck down the MPPC saying that “A patentee may simply enforce his right to exclude infringement, but he must not use his patent ‘as a weapon to disable a rival contestant, or to drive him from the field,’ for ‘he cannot justify such use.’” In other words, Edison’s monopoly was busted by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.

The ruling made it so that Hollywood could now legally flourish without any threats of lawsuits or mob attacks.

Edison, much to his own dismay, was probably the biggest individual influence on Hollywood as we know it today. Without his cutthroat, and eventually illegal, business practices, there is a good chance that West Orange, New Jersey would still be home to the film industry and that Hollywood would just be another town outside of Los Angeles.

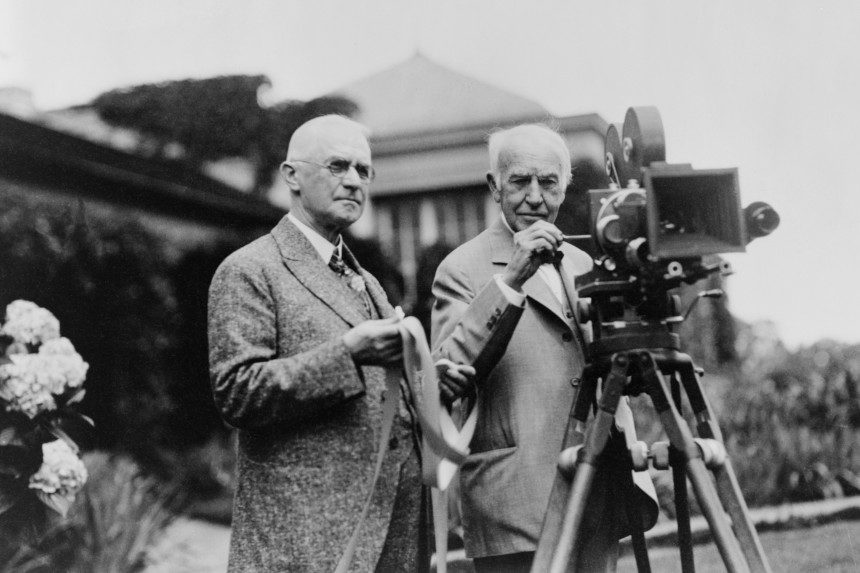

Featured image: George Eastman (left) and Thomas Edison standing with motion picture camera circa1925 (Everett Collection / Shutterstock)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thomas A Edison Jr said education rule the nation especially history knowing your roots and knowing where your people and where they actually came from to make it through the “struggle” to make away everybody coming from the genus kid ! aka william L . Jr ,Mr. williams ,” Charles Edison!”

Well, I was never taught ANY of this about Edison in school. Just about his genius, tenacity and most important inventions. His connections to the (then) expanding motion picture industry in New Jersey made perfect sense after reading this feature.

It’s understandable that Edison would’ve had to have his guard up at all times to not have had all of his hard work (and money) taken away, without him being able to do anything about it. It had gotten way out of control well before 1915 though, and needed to be successfully busted by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.

What followed over the next several decades with films, movie starts and television’s Golden Age was marvelous, but like the heyday of the American auto and music industries, have now long been very small, distant shadows of their former selves.